Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The glass factory in Dundee has a tremendous history going back to the 1880s and a wonderful bank of memories and esprit de corps among the people who worked there - some their entire lives.

In the late 19th Century there is evidence of glass being made in the Dundee area. Talana Museum has an invoice for the supply of glass bottles in 1889.

However, this production became properly business orientated in 1917 when Mr Cook moved his factory from Durban to Dundee. He had four glassblowers producing glass, but needed to find a source for sand. Rather than cart the sand from Malonjeni very close to Dundee to Durban, it was decided to relocate the glass business to Dundee which could supply the sand as well as the coal for firing the furnaces.

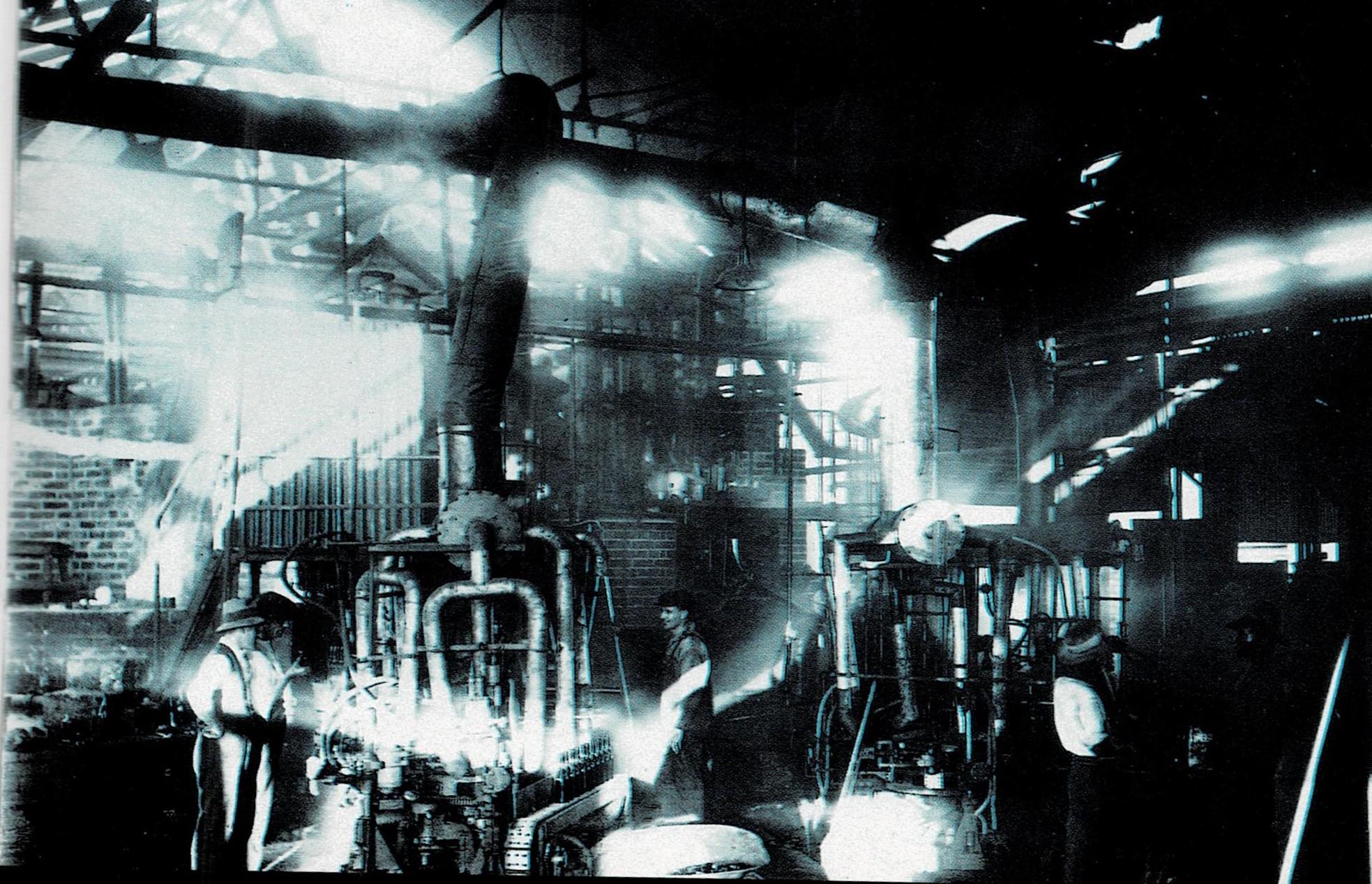

First Union Glass Factory (Talana Museum)

By mid 1918 the Dundee Coal Company had agreed to lease its old buildings to Glass Ltd. The pot furnace and glass blowers were relocated and a semi-automatic bottle machine arrived from Britain.

In 1918, to raise capital, the syndicate floated the glassworks as a small public company, named “Union Glass” as a tribute to the new Union of South Africa. Broken glass and bottles (known as cullet) were added to the mix to melt the ingredients – this came from agents in different areas and sand was dug from the bed of the Malonjeni spruit.

Production at Talana was carried out by three teams of five men: the bottlemaker, gatherer, blower, wetter-off and taker-out. All bottles were hand-blown with the help of hinged iron moulds worked with foot pedals.

By October and November 1918 the Spanish flu had so many workers off sick that the factory could scarcely keep going. As an indication of how this pandemic affected Dundee and the area, the Dundee cemetery register book used a portion of a page per year, for deaths, before 1918. The 2 months of October and November occupy 5½ pages.

Another threat was the talk of a rival glassworks in Dundee. The South African Breweries wanted to buy a section of land and set up a beer bottle producing factory.

In 1919 the directors of Union Glass offered to co-operate with the Breweries and it was agreed that the Breweries would take up a major share in Union Glass. The factory was enlarged to meet the demand for increased production and new semi-automatic machines were imported from Britain. At this stage the factory produced beer and mineral water bottles, ink and medicine bottles. Coal from Talana hill was used in the furnaces.

The post war recession in 1922 impacted badly on the factory, which was eventually forced to close due to the lack of orders. They were closed for 15 months until June 1923, when they reopened, with the belief that they would be given a 25% tariff reduction against imported glass products, but this did not happen, as “wine merchants, breweries, mineral water people and others” petitioned the government to keep the status quo. Thus with the re-opening they realised that they had to produce a first rate product to compete with imported bottles. The first fully automatic machine, a Lynch, was ordered from Britain. This was coupled with a Rankin feeder known as the Rankin “flow system”. The inventor, Mr Rankin was brought out from the UK, to supervise the installation and spent 2 months at the factory. He brought with him Mr Sutcliffe, a consulting engineer, who supervised the restarting of No 2 furnace. The Lynch machine and Rankin flow system were a considerable success, so much so that a second Lynch machine was ordered in 1924 - this one was coupled with a Hartford gob feeder.

For anyone not familiar with the technical terms associated with glass making the “gob” is the first elongated blob of molten glass that comes from the furnace and is gravity fed into the mould. A newspaper reporter in 1927 recorded this function as “the required amount of molten glass is delivered by the feeder and automatically cut off by oiled shears. This gob of glass flows rapidly down the chute into the waiting blank mould on the machine below, and it is in this position the ring or top of the bottle is formed. As the revolution starts, the machine moves to the transfer position, where the bottle in embryo is handed over to one of the six blow moulds…”. The weight and shape of a gob is important in the formation process for each type of glass container being made.

In 1924 Union Glass exercised their option, and bought the entire 1200 ha property from the Dundee Coal Company, with 25 cottages, all occupied by their employees and families. Most of the land was leased to tenants and wild grass was harvested and used in packaging orders, to cushion the bottles. The bottles were packed in second-hand sacks cushioned against breakage and rubbing against each other by the grass.

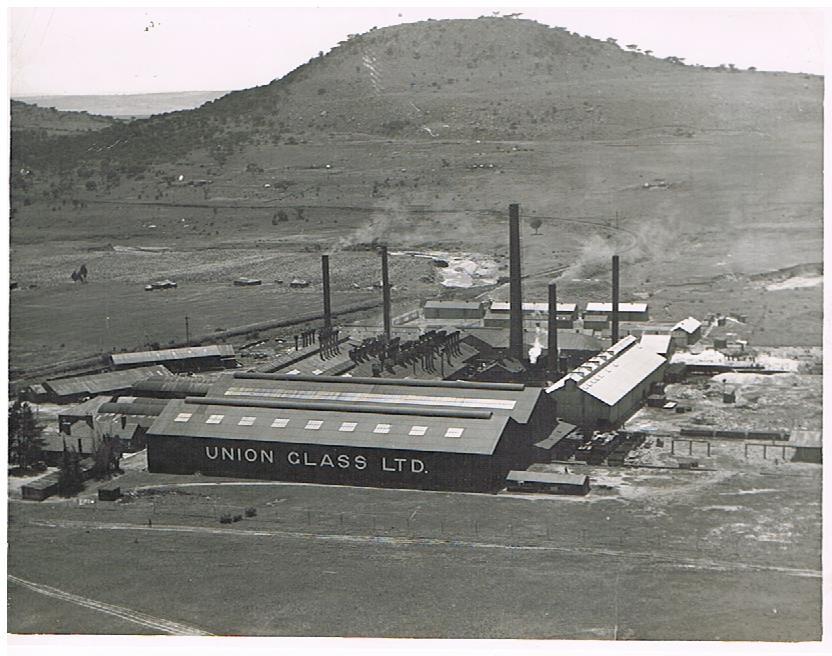

An early shot of the factory (Talana Museum)

The soda ash needed for the production process, was brought by rail from the Transvaal. A special Talana siding was built to support the factory.

From the start the factory had only made dark green bottles, as this is what South African Breweries wanted for their beer bottles. However, market research indicated that there was a market for colourless or “white metal” glass. This required very high quality sand, and that from Malonjeni did not meet the requirement. Adverts for the correct quality sand, were posted in all the national magazines, inviting potential suppliers to send sand samples for analysis.

Among the replies was one from GA Hubach, on the Cape Flats from a small farm, Phillippi. This proved to be greatly superior to all other samples and despite the distance, in April 1925, Union Glass signed a contract with Mr Hubach for the supply of cleaned sand on a regular schedule. He was also supplying other non-glass customers. The sand was sent by rail and gradually Malonjeni sand was phased out.

The company was attracting a lot of new customers, including mineral water bottlers in Johannesburg. Unfortunately the first batch of bottles to be filled, was a disaster as the bottom of the bottles fell out, due to poor annealing, in the makeshift lehrs at the factory. The bottler did not realise this and instructed his workers “not to squeeze the bottles so hard.” A new and improved gas lehr was ordered from Britain and after an initial operating problem was resolved, and the annealing process improved, no more bottoms fell out of the bottles.

By 1926 there was still no tariff protection against imported glass bottles. A shipping freight war also added extra pressure and “overseas bottles were landed at such a low figure as to make it almost impossible” for Union Glass to compete. The company was still not making a profit and independent shareholders were demanding that men with special expertise by recruited from Britain on a permanent basis. Three men came out, brothers, Bert and Ernie Arnold (who had experience of automatic machines) and Bob Adamson who specialised in furnaces and lehrs.

Bob Adamson proved extremely capable and in 1927 was appointed as the factory works manager. That year a Natal Witness article reported that “more than fifty Europeans and two hundred natives are employed.” The factory buildings were dominated by the three tall chimney stacks, one of which was 40m high. The reporter toured the entire factory and noted the batch house, where the mixing was carried out, the “huge gas producers” and No 2 furnace which could hold 110 tons of molten glass. The batch, including cullet was manually loaded into the furnace “doghouse” at intervals of 15 – 20 minutes, with a total of 25 tons per day. The furnace reached temperatures of 1400-1600°C. At the furnace’s working end were the 2 automatic Lynch machines.

The reporter also visited No1 furnace which was only semi-automated. The glass was “gathered by hand on a long rod and dropped into the mould, the required weight being judged by eye and the glass severed by hand shears.” This furnace also had 2 glory holes which were used by hand blowers, making ink and other bottles in a foot mould. The average daily output of all the different bottles was between 21 600 – 28 800.

In the mould shop engineers made the dies and moulds for each of the bottles being manufactured. Trade marks, names and other identifying designs were cut into the mould with hammer and chisel and had to be done very carefully and cleanly to ensure crisp markings on the glass bottles.

In mid 1927 the factory manager resigned and Bob Adamson was promoted to the position. A new works chemist, M Wilsker, was brought out from Britain on a three year contract.

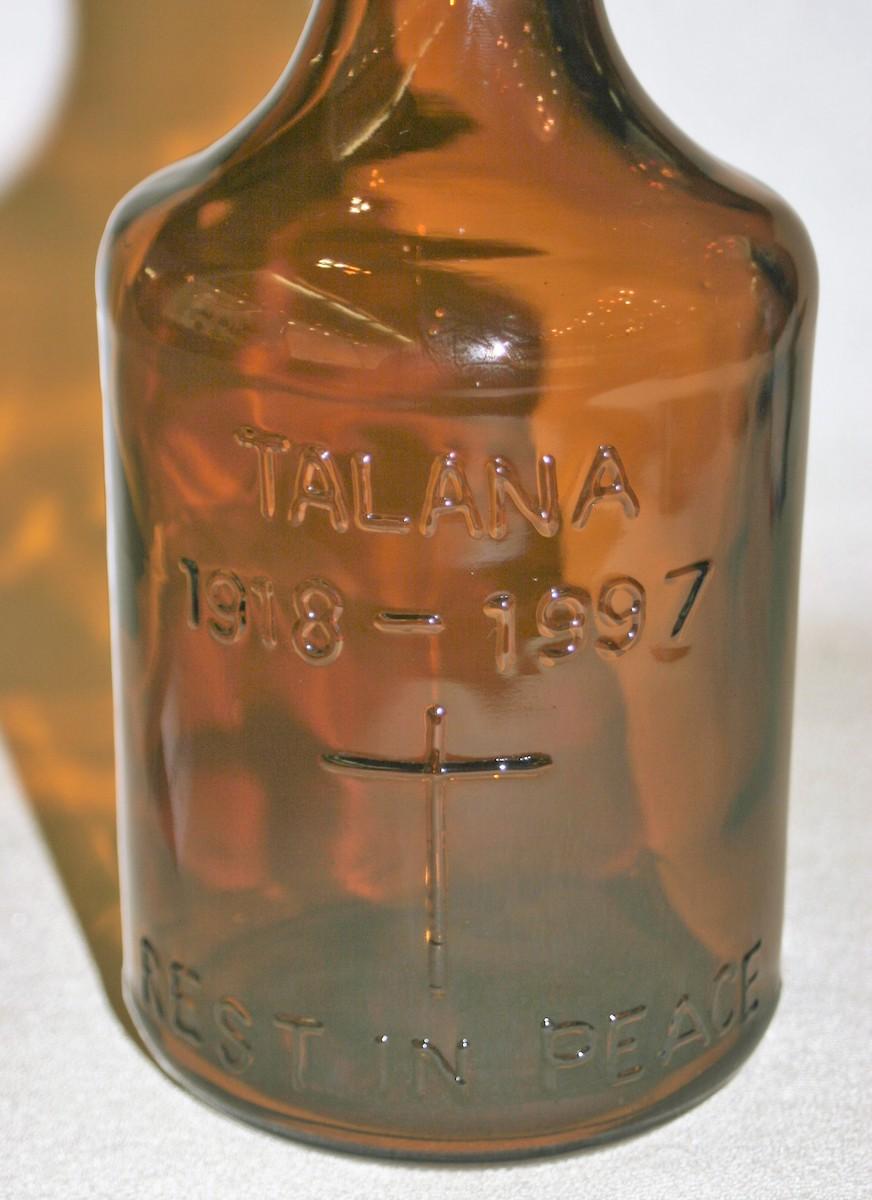

Each year the factory became more versatile and expanded the range of bottles produced. Milk bottles were introduced, which had to be assized by a government official, to ensure standard capacity. Preserving jars made their appearance, as did the embossing of the base of the bottles with the name TALANA and a letter signifying their year of manufacture. A being for 1928, B for 1929 etc. It was also decided that they would make glass in four colours – white, pale green, olive green and dark green.

In December 1929 the government raised the tariff on imported glass from 5-25%, which allowed South African glass to enjoy more public support. In 1930 the company bought a Monish Monir machine, able to make small bottles, appointed Tauber & Corssen as national sales agents and also introduced a decorating department that allowed for coloured permanent enamelling on bottles. The company continued to have ups and downs – international competition, the Great Depression and the suspension of the Gold Standard and the opening of a glass factory in Pretoria all affected the factory and the levels of orders and production.

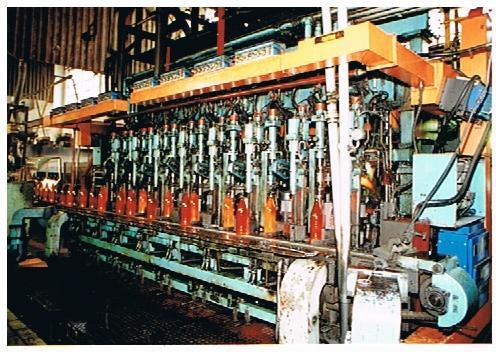

Monish forming machine in action at Union Glass (Talana Museum)

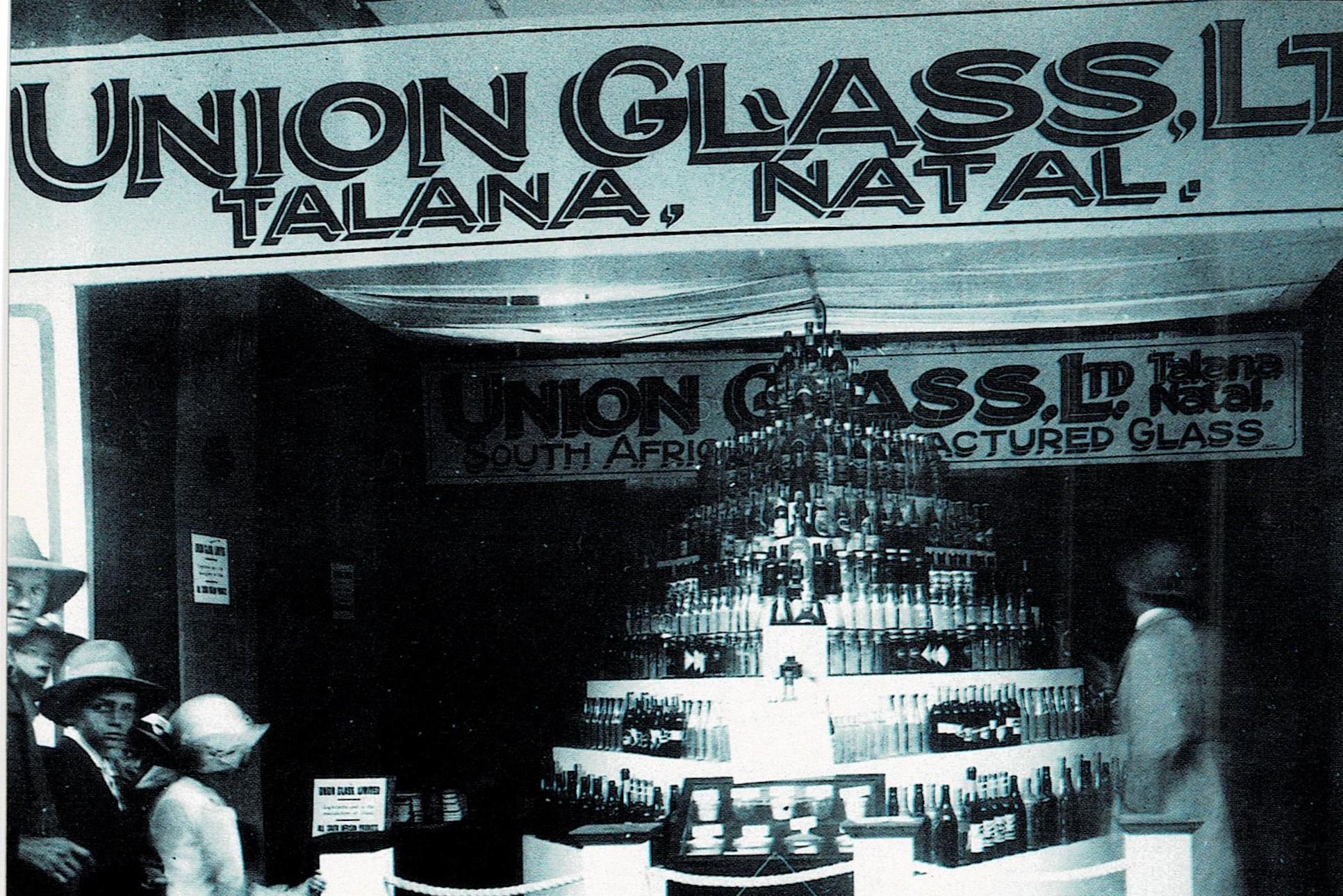

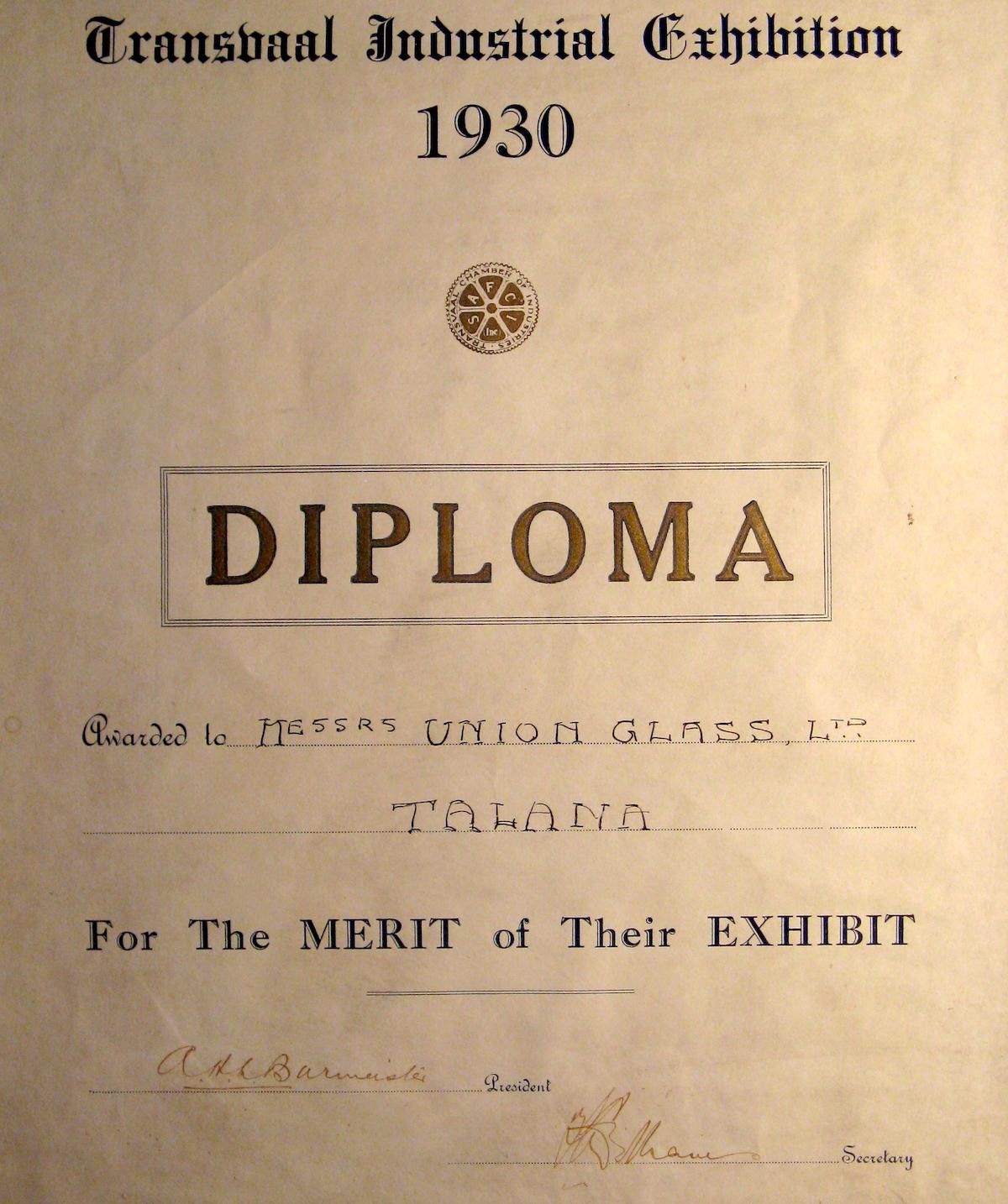

New sorting sheds were built and finished bottles were stored indoors in organised lines. The marketing department had exhibits at various Agricultural and Industrial Shows throughout the country to market the range of products.

Union Glass Exhibit at Rand Show 1927 (Talana Museum)

An exhibit award (Talana Museum)

In 1934 two more Monish machines and a new lehr were installed and more men recruited to operate them. These machines rotated slowly and the operator needed to swab the moulds regularly, with a sacking bound swabbing stick. He also needed to take regular samples, which entailed removing an emerging bottle and weighing it. If the weight was wrong he had to climb up steps to the forehearth and adjust the plunger mechanism, which regulated the flow of glass. Ernie Arnold was Talana’s expert feeder. Berridge Wade was one of the machine operators and Lionel Rettman, Johnny Abrams, Johnny Vlok and Smarty Nel were the shift foremen. Only the foremen were permitted to change machine settings.

Pretoria Glass opened and Mr Wilsker left to be the works chemist. Many of the Talana men left, being attracted by the higher pay.

In August 1937 the sorting sheds burnt down, including almost all the bottle stocks. Talana bought a pavilion from Johannesburg’s Empire Exhibition to replace the building. Although insured, customers had to wait for orders to be filled.

In 1939 as war clouds loomed, new automatic machines were ordered from America. As the war continued the demand for Talana glass escalated, as no glass could be imported due to ships all being used for the war effort. Many of the men had joined the armed forces and this placed even more pressure on the factory. Some were declared “key men” and were obliged to remain in their positions, much as they wanted to join up, they were not allowed to.

In 1940 furnace no 3 was commissioned, plus a new electric controlled lehr. Talana Glass was in considerable demand and on several occasions orders had to be refused – but it was policy to give preference to established customers as much as possible. In 1941 they introduced the promotion and selling of their products, through their own representatives, rather than agents.

In 1942 the South African government introduced glass control and this affected the factory. Customers had to apply for permits and a government scale of prices was enforced. As pressure for orders grew, the factory expanded, and new machines were ordered from America, but took a long time to arrive because of shipping delays, due to the war. The business manager was Bill Harrison (who had fought at Delville Wood in the First World War).

In 1944 the factory expanded and commissioned number 4 furnace to cope with the demand for bottles. With the increase in orders, new furnaces and automated equipment, the factory was at last able to pay a dividend to their share holders.

With the end of the war in 1945, glass rationing was lifted, but not the government price controls. However, demand continued to exceed the capacity of both Talana and Pretoria Glass. By 1946 Pretoria Glass became part of Anglovaal and formed the nucleus of Consol. Union Glass was more than twice the size and the directors and management intended to keep it that way. For the next few years they were able to do so. They expanded the colours of bottles they were producing to include amber for beer bottles, green champagne bottle and the new blue pharmaceutical bottles.

There were plans to expand. The village had 20 new houses, 10 of which were earmarked for highly-skilled new men who were being recruited. Bottles were still being railed to customers in sacks – all recycled. Most of the customers returned them for reuse. The sacks included grain sacks used to deliver mealies to the hostel, supplied by second hand dealers, or from Lake Magadi in Kenya, with supplied the factory with soda ash. They had to be washed to rid them of the alkali and also at times mended to repair holes. As these hessian bags were strong they were also cut into strips to create swabs for cleaning out the moulds, wiping their hands and faces and protecting their hands from the heat.

Workers at Union Glass loading sacks onto train (Talana Museum)

Many of Talana’s simple moulds were made in a foundry at Hattingspruit, 10km north of Dundee. More complicated designs and those bottles requiring a super smooth finish, came from Johannesburg.

Men learnt very quickly that working in the glass factory meant exposure to heat. Many could not take it and left the factory. The machines were all designed to run 24 hours a day and operators worked in 3 eight hour shifts and were paid a bonus on output. The production target depended on the type of bottle being made. 90% of the target entitled the men to a full bonus. As production dropped, so did the bonus. At 58% or lower no bonus was paid. These bonuses were paid each Friday. A full bonus meant an extra £1/10/0 a week (about R220 calculated to today) and made a big difference to the take home pay.

In 1950 Number 5 furnace was commissioned, but a week before start-up they found that the foundation of the back of the furnace sagged by 4cm. This was as a result of old mine workings under the factory floor. Repairs were not possible- all they could do was adjust the feeders.

The No 5 complex was equivalent to a whole new factory with 3 new Lynch 10’s and a four section IS at the furnace’s working end. The workforce was increased and in 1951 there were about “200 whites and 850 natives” employed at the factory. By now the factory was producing 3 million containers a week. The choice of so many furnaces made it easy to change between the five colours being used – flint, amber, blue, emerald and dark green. The new machines were also equipped with automatic stackers in place of the human takers-out.

On the surface all appeared well with Talana Glass, but below the surface there were many problems. To finance its many projects, they had borrowed money from SA Breweries. South African Breweries, Talana Glass and Pretoria Glass all wanted to expand and build glass works in the Cape to supply the wine and beer industries. In 1954 after discussions, it was realised that there was insufficient market share for all of them to build factories. Agreement was reached on Consol acquiring Union Glass – SA Breweries held 78% of the shares and agreed to the offer, as did the independent shareholders.

It was not an easy transition for the staff at Union Glass to be incorporated in Consol glass and their methods of management and many of the men left. Morale was low and a lot needed to be done to integrate new ways, new management and new ideas.

In 1955 there was a strike by the Zulu workers, who wanted an increase to a minimum wage of £1 per day. This strike quickly spread throughout Natal. The strikers picketed the entrance to the factory and the situation appeared so threatening that the women and children from Talana village were evacuated and taken into Dundee for safety. The police arrested the strikers, 578 men were taken into custody. They were released on payment of a £5 fine. All were discharged from service. There were a considerable number of Zulu, as well a group of Malawis who had not participated in the strike, that helped keep production going. Word spread quickly about the availability of jobs and hundreds of people arrived and were employed- but they all needed training.

The Talana factory recovered quickly and a whole series of image-building adverts promoted Consolidated Glass Works as “Bottle-makers to the Nation.”

In 1956 the factory at Belville, in the Cape went ahead, on the land that Talana Glass had purchased. To start with, this factory would only produce flint glass. Cape wineries would still have to order their green or amber bottles from Talana. In July 1956 there was a disaster in the Talana factory. The floor under the No 5 complex collapsed and the lehrs section of the production fell into the basement. Flames shot up and very quickly the whole area was burning. Men rushed to the scene to fight the fire and to save the forming machines. They managed to do so and the inspection afterwards showed the fire starting in stocks of flattened cartons, which were now replaced the use of sacks for packaging bottles. The steel beams that supported “the floor had got so hot that they had curled”. The investigation never managed to identify the cause of the fire, but the furnace and forming machine had not been damaged and there were no casualties. However No 5 furnace was going to be out of action for 6 months. To fulfil orders the Belville factory would need to step up production. 10 Talana volunteers went off to train new men to operate the production lines.

There was a lot of discussion about rebuilding No 5 furnace, or relocating the whole factory closer to Durban, which created a lot of uncertainty, but in 1957 the rebuilding went ahead. However, that year also saw a sudden decrease in the demand for bottles and Consol had to temporarily close furnaces at their Wadeville plant and decided to close Furnaces 1, 2 and 3 at Talana. They closed them permanently and they were broken up and sold for scrap.

Milk bottles, pints and quarts for beer were the staples of the Talana factory. In 1959 they brought in a new much lighter bottle with thinner walls for beer. Originally known as the “bantam”, this soon was renamed the “dumpy".

In October 1960 Anglovaal bought out the SA Breweries 30% share of Consol, thus increasing their holdings to 61,3%.

The Talana factory was now firmly in the Consol stable and ceased to have its own identity. The marking on all bottles carried the Consol triangle mark. There continued to be ups and downs. In 1980 Consol built a new factory at Clayville to meet the increased demand for beer bottles. In 1988 the Talana factory was the first to meet the South African Bureau of Standards system, today labelled SABS ISO 9000.

Talana retained its own special culture within the Consol group. 85% of their production went to Natal customers, but all green beer dumpy bottles for the entire country were produced at Talana.

Although on paper it appeared that Talana had problems; technology was dated, raw material came from considerable distances, markets were far away but in practice their manufacturing costs per ton were the cheapest of all the glass factories. These factors that were to raise their head a few years later and with the problems of the undermining of part of the factory, led to the closure of the factory in 1997. The equipment was redistributed to other factories, the Talana village flattened and many of the factory buildings demolished. Some remained and the circle turned. Today Buffalo coal has re-used some of the buildings and concrete floors for their coal business.

Talana glass factory before demolition (Talana Museum)

The last bottle off the Talana Glass Production Line (Talana Museum)

The incredible glass exhibit remains on display at Talana Museum and the Board of Trustees continually add new pieces, that we believe should be included and on public display. All records and history of the factory were secured by and are protected at Talana Museum.

The exhibit at Talana Museum

A Talana Glass Ashtray (Talana Museum)

80 years of glass production created an incredible legacy, a close knit group of employees who have amazing stories to tell of their life at Talana glass and an industry that helped shape our town.

About the author: Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. Since 1983 as curator, Pam McFadden has developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. As part of the museum collections she has collected and created an extensive museum archive, that holds many treasures.

References

- Talana Museum archives

- Spirit of Consol, Anthony Hocking, 1994

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.