Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, Lucille Davie traces the rise and demise of the famous Amawasha in Johannesburg. The piece was first published on the City of Johannesburg's website on 3 April 2006. Click here to view more of Davie's writing.

Main image: A new development is rising on the site once occupied by the Rand Steam Laundries and before that the AmaWasha.

At the turn of the 20th century, Johannesburg had an unusual group of self-employed businessmen carving a place for themselves in the mad scramble for gold.

The AmaWasha, or Zulu washermen, formed a guild, which gave them privileges that blacks at the time could only dream of as they were systematically deprived of their rights to earn a living as they chose.

These entrepreneurs had an impressive presence - they wore turbans and marched into town in regimental style once a month, keeping perfect time and singing their old regiment songs. At the market square they would get down to a sociable imbizo after they'd renewed their monthly licence. By 1896, a decade after Joburg was established, there were more than 1 200 AmaWasha cleaning the town's laundry. But by 1914 the authorities had successfully marginalised them and the industry was largely dead.

Marching into town (New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand, 1886-1914)

The guild exempted the AwaWasha from carrying passes and got around a local by-law that prevented blacks from carrying weapons. It also allowed them to brew as much beer as they wanted for their own needs, according to Charles van Onselen in Studies in the Social and Economic history of the Witwatersrand, 1886-1914, New Nineveh (1982).

The guild allowed them to restrict entry into the AmaWasha and to determine the price they levied for washing the town's laundry.

Van Onselen says that despite the fact that these men managed to save fair sums of money, it was spent on land and cattle in the countryside and not used to buy laundry equipment. They did not keep up with the next phase of industrialisation when, for instance, the Randlords were on hand to supply the capital needed to take mining below ground.

"In a period otherwise characterised by growing African proletarianisation, however, even this form of re-investment was enough to ensure the washermen a significant measure of economic protection and in parts of rural Natal the AmaWasha came to constitute a conspicuously successful stratum in black society," Van Onselen says.

By this means the AmaWasha and their children avoided the movement from the land into the fast-growing black working classes that characterised the country at the beginning of the 20th century.

The AmaWasha had observed the turbaned Dhobis, India's washermen caste, doing Durban's washing in the Umgeni River in the 1870s. They soon adopted the same form of earning a livelihood, after noticing that the Dhobis could not meet the town's laundry demands.

When gold was discovered in Joburg in 1886 the AmaWasha, in particular the Mchunus and Buthelezis, moved up to the reef, along with a number of Hindu Dhobis, Van Onselen explains.

Unique circumstances

Circumstances in the gold-rush town were unique in two ways. Firstly, there was no large river residents could easily empty their waste into, which meant they could not do their washing at home. So washing was allowed in streams on the outskirts of town.

Secondly, there were very few women in the town for the first 15 years or so, and gold prospectors, single or married without their families, were "without recourse to that female labour which normally undertook the washing and ironing of their clothes".

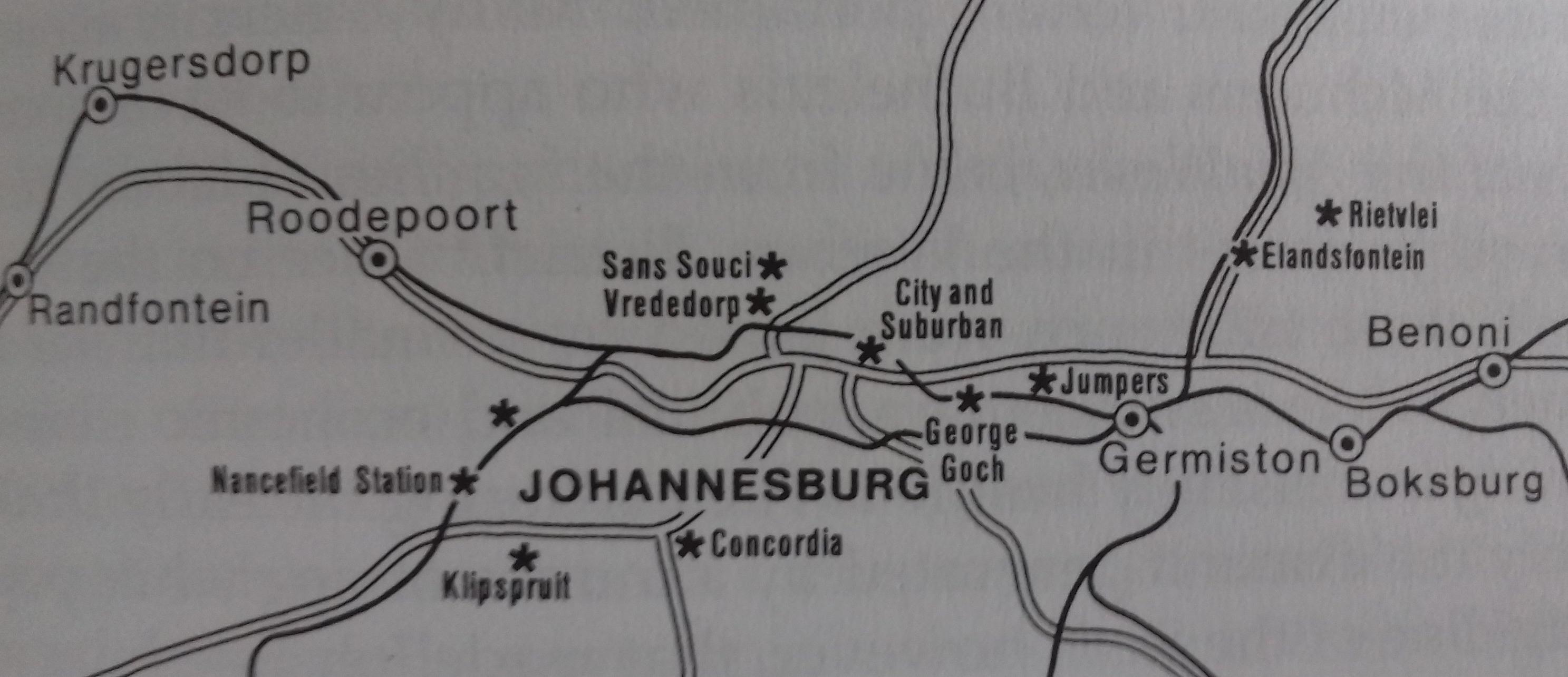

The AmaWasha took up the challenge and set up shop at Braamfontein Spruit to the north of the town; by 1895 their operations had extended to three other sites - Elandsfontein in the east, and Booysens and Concordia in the south. A year later, in 1896, there were more than 1 200 washermen at about 10 sites - Sans Souci, Vrededorp, City and Suburban, Rietvlei, Elandsfontein, George Goch, Booysens, Concordia, Klipspruit, Nancefield Station - washing the town's laundry over boulders and in specially constructed concrete troughs.

Principal Washing Sites on the Witwatersrand 1890-1906 (New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand, 1886-1914)

At the Sans Souci site a group of about 80 men established themselves more permanently. They planted crops along the banks of the spruit, kept pigs and cattle, had 14 horses and four carts. By 1896 a census showed that the group had grown to 546 Zulu washermen, 14 Dhobis, four Indian women and 64 black women.

Although the community was very much an urban set-up, it retained social structures belonging to a traditional rural setting. An induna was in charge of the settlement, recruiting new men, organising a watch to guard the drying washing and, most importantly, he was the go-between for the men and the land owner, the Braamfontein Company, and the municipality, both of which were paid fees.

Van Onselen says that "vestiges of the Zulu regimental system were woven into the fabric of the washermen's guild". And between 1890 and 1895, the leader of the guild, "the formidable Kwaaiman", would meet with the other indunas in the market square once a month for a chinwag.

Predictable routine

The washermen's week took on a predictable routine. Mondays were usually collection and delivery days, by horse and cart, or more usually by slinging large bundles over sticks and walking to their customers. Laundry fees were also collected on Mondays.

Tuesdays to Saturdays were devoted to the serious business of cleaning the town's dirty laundry, with a possible break for a mid-week afternoon delivery. Sundays were days of rest.

The average washerman washed three bundles of washing a day, or about 18 bundles a week, for which he earned a monthly wage of £14. Over his four-month spell in the town, he would earn £48. But he had to balance this against his costs, which totalled £7 over the four-month period, Van Onselen says.

He had to pay a Sanitary Board registration fee, a monthly licence fee, rent on a hut, site hire and a pass exemption fee. Additional under-the-counter income came in the form of the "less scrupulous washermen who stole or sold their customer's clothing", and the illegal sale of home-brewed beer.

Most washermen spent two sessions working in the town, going home to KwaZulu-Natal to their families in between and taking home up to £100 every year. "Incomes of this order placed the AmaWasha in a rather exceptional socio-economic category and, not surprisingly, their children, when subsequently questioned about their father's position in rural society, deemed the washermen to be wealthy."

From 1894, however, the authorities had to deal with a constant stream of complaints about the loss of their laundry. A raid in that year on a washing site produced 10 "missing" bundles of laundry.

At one time the selling of clothing became an organised mafia operation, explains Van Onselen. In 1895 a gang called the Peruvians - Russian or Polish Jews - ran a well-organised operation that sold second-hand clothing in the town. It could conceivably happen, says Van Onselen, that "a white miner who had sent his laundry for washing with the guild would end up having to repurchase his own garments from a second-hand clothing dealer in the city centre".

Changes in 1895

But things changed from 1895 when a drought set in. The pits that the washermen dug into the banks of the Braamfontein Spruit were not washed out by the constant stream of water. The usually dirty and discoloured water, mixed with decomposing soap and mud, became disgusting and posed a health risk. Health inspectors ordered a temporary closure of the site and a thorough clean-out of the pits.

Other moves were afoot that were to signal the beginning of the end of the AmaWasha. In October 1895 the Crystal Steam Laundry Company was established in Richmond with the newest plant and equipment imported from the United States. Shortly after this, in June 1896, the Auckland Park Steam Laundry Company was formed.

And the authorities began looking for a single, consolidated site for the washermen. A site to accommodate 1 500 of them, on the Klip River on the farm Witbank - a two-and-a-half hour train ride south - was proposed. Kwaaiman expressed his unhappiness to the Sanitary Board but was ignored. The board started to pressure the AmaWasha to move, and a month later the screws were turned - the board refused to renew their licences to operate in the town.

A mass meeting was held on market square, led by Kwaaiman, who then approached the board again, only to be told that once all the current licences expired, washing could be done at Klip River, or not at all.

This led to divisions within the ranks of the AmaWasha. Three days after the meeting, some AmaWasha moved down south. A few days later, several hundred men left the town and went back to their rural homes in KwaZulu-Natal. Some men got jobs as domestic servants. But households soon discovered that up to 40 percent of the AmaWasha were no longer available to do their washing.

Two things then happened: the remaining men went on strike for a week, and the men down south took advantage of the strike and doubled their fees. "By the end of the week Europeans were either starting to wash their own clothing at home illegally, or reluctantly paying the 100 percent increase to meet the weekly laundry bill," Van Onselen says.

But then, just when their actions seemed to be a serious inconvenience to the white townsfolk, their resistance started to crumble. From December 1896 more washermen moved down south. "Lack of leadership, the need for cash, the presence of the new steam laundries, and scabs' at Witbank all combined to undermine the morale of the AmaWasha, and by the last week of 1896 most of the washermen's guild was at work in the Klip River."

Life at Klip River

The move down south necessitated a huge change in the lifestyle of the AmaWasha. They now had to rely on the Netherlands South Africa Railway Company (NZASM) to transport bundles of washing to and from their customers, at exorbitant prices. Eventually the Sanitary Board managed to get the NZASM to reduce its prices but another railway problem reduced their output, and therefore their income.

The quality and frequency of the service was a headache for the washermen. They were forced to transport their bundles in empty coal trucks hardly suitable for clean washing. And the NZASM's timetable meant that the washermen could not make their deliveries and collections in town in one day.

Their troubles went further. They could not grow crops at Klip River and had to buy provisions from the local store at uncompetitive prices. Since they were further from town and potential customers, they could not sell beer to bolster their income. Four black policemen and a feared Constable Botha kept a close eye on operations, thus eliminating any chance of illegal second-hand clothes selling.

Squeezed in this manner, says Van Onselen, they did what most businessmen would do: they increased their prices from "four shillings to eight shillings for a bundle of washing in an attempt to cope with the new cost structure that had been imposed upon them a 100 percent increase".

At the same time mechanised laundry washing was fast gaining ground in the town. By April 1898 there were some six laundries operating, having taken advantage of the changes happening to the AmaWasha.

The Melrose Steam Laundry was opened on the banks of the Jukskei River in April 1897 and recruited Dhobis. In 1899 these Hindus asked the owners of the land for a piece on which to build a temple. The Siva Subramanian Temple, a wood and iron structure, was largely demolished in 1996 to make way for a new temple, now an incongruous structure in the plush suburb of Melrose. The laundry operated until the depression of the 1920s.

Back to Richmond

While most of the AmaWasha had moved to Witbank, 60 men were persuaded by Lady Drummond Dunbar to remain at Richmond. Of course, they soon ran into trouble with the Sanitary Board over the issuing of licences, but this time they had an ally.

Dunbar promised to protect them if they applied for passes, the legal requirement at the time for all blacks. They then became her "servants", giving up their pass exemption status, but continuing as washermen.

The Sanitary Board immediately prosecuted them for trading without a licence. Dunbar and the land owners sprung into action - they challenged the Sanitary Board and "organised a public petition for the return of the AmaWasha and the cheaper laundry service which they provided".

The battle that lasted six months and in July 1897 Dunbar eventually won; the AmaWasha were invited back to their old sites and by September there were no washermen in Witbank.

Even better conditions awaited them - they found they had warm soapy water on tap, discharged from the Crystal and Palace Steam laundries. However, things would never be the same again. The guild was not as cohesive and missed the strong leadership of Kwaaiman, without whom their disciplined marches and meetings in town were not the same.

"This loss of internal control manifested itself in the growing number of reports of theft, gambling, drinking and violence that came from the washing sites between 1897 and the outbreak of war [in 1899]."

The council felt the need to intervene, using the only means left to it: to formulate new by-laws. But before the laws could be implemented, the South African War broke out and the majority of the AmaWasha left for their rural homes in KwaZulu-Natal. Others were employed by the British army, which took occupation of Johannesburg in May 1900.

The British authorities set out to "enhance control and segregation by attempting to get all urban Africans to live in a single consolidated location".

Down south again

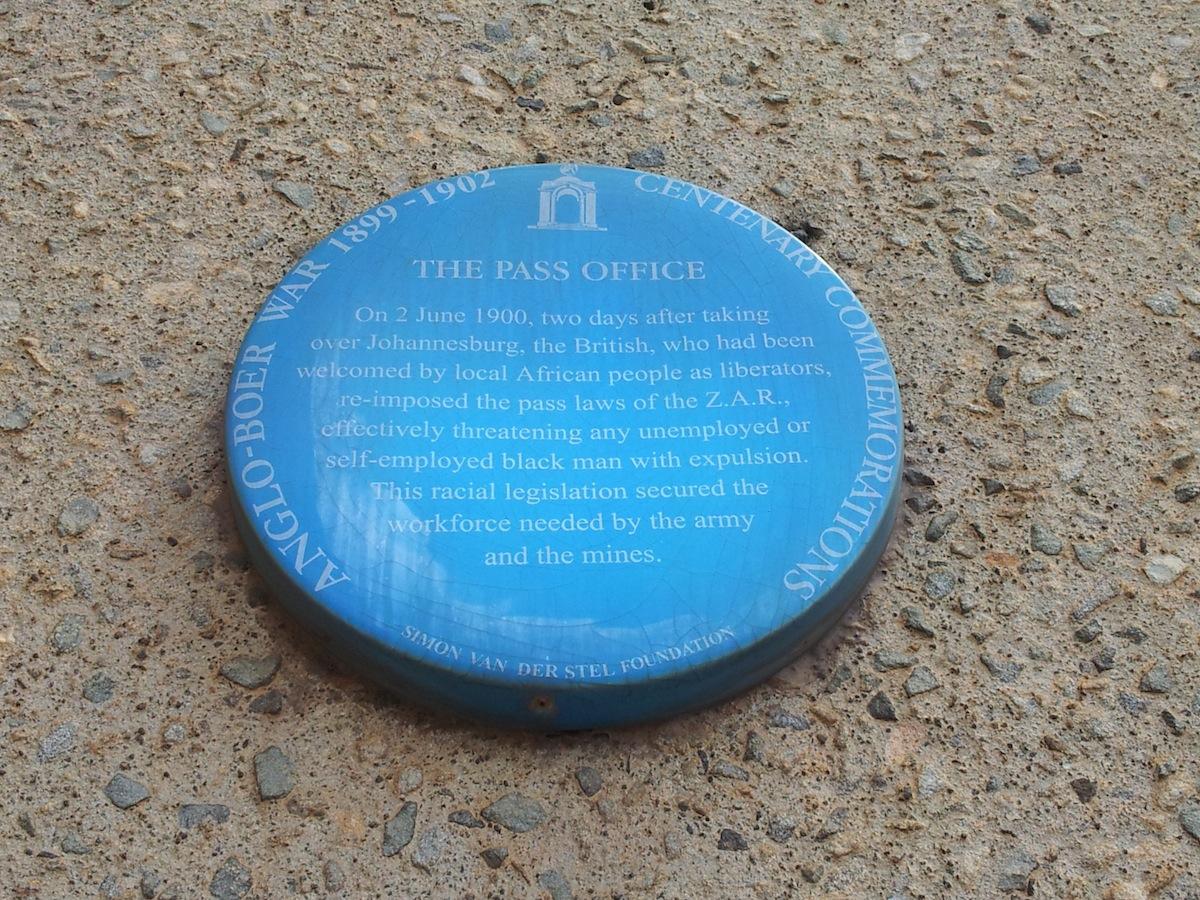

A new British pass law disallowed the pass-exemption provision - a big blow that sought to reduce the AmaWasha's central competitive site at Richmond and reduce them to the status of servants. In April 1902 this site was cleared of all washermen and they were moved to Concordia, again down south.

Blue plaque marking the site of the pass office established after the British occupation of Johannesburg (The Heritage Portal)

What they didn't know, though, was that this was only halfway to their final destination, assisted by the outbreak of plague in 1904, when the council cleared the "Coolie Location", just west of Museum Africa, for fear of the disease spreading. The council acquired the farm Klipspruit, 21 kilometres south of the town, and by May 1904 all the AmaWasha were moved there, to join the new residents who had been resettled in the area.

This move was not without protest. In March 1904 a mass meeting was held in market square, attended by the Brickfields residents. The Amawasha led the crowd in the singing and chanting, in a déjà vu experience - they'd been expelled from the town in 1896.

Of course these developments played into the hands of the laundry capitalists, who experienced a rise in business as people streamed back into the town after the war. Laundries expanded and Rand Steam Laundries in Richmond was formed at the site of the biggest from 1890. It operated on the site until 1962.

Rand Steam Laundries before demolition (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

The AmaWasha, emasculated in their new location, did what they had done in 1897 - undertook a mass re-entry into the town. This time, however, new segregatory legislation denied them access to their old centralised sites and instead they set up shop in peripheral sites at Claremont, Craighall, Concordia and Langlaagte.

But the authorities had long-term plans. By early 1906 an ironing room, a fenced-in drying site and 100 concrete wash basins had been erected at Klipspruit.

"With blind ruthlessness and staggering cynicism the council prepared to move the washermen for the last time - this time to an uneconomic washing site that shared its setting with the municipal sewerage works," Van Onselen says. Today remains of the sewerage works are still visible but the basins have disappeared.

Under pressure from the council, some washermen packed up and left for KwaZulu-Natal. In early 1907 about 75 washermen moved out east and rented sites on the farm Elandsfontein, but the back of the manual washing industry had been broken.

By that year 300 wash basins in Klipspruit had been built. Yet combined with expensive licence fees, the industry slowly started to die. And there was another factor, a repeat of an earlier problem.

"As had been the case at Witbank 10 years earlier, it was the absence of cheap and efficient rail transport that did most to ruin the small businessmen who had been relegated to a segregated site miles out of town."

Of course, this eroded their customer base. And worse was to come - a depression hit the Witwatersrand between 1906 and 1908, with working-class whites joining the ranks of the unemployed. The small group of washermen at Elandsfontein resisted pressure to move south. Instead they first moved further east to Rietvlei, but by December 1907 they had all moved to Klipspruit.

Another nail in the coffin

Another nail in the coffin of the AmaWasha was a new contingent of washer people - Chinese and Indians. By 1914 there were 46 Chinese laundries in Johannesburg, located in Fordsburg and Jeppe, where some of the AmaWasha were employed. They serviced the surrounding white working classes, which meant they didn't need horses and carts. Indian laundrymen established themselves in the outlying areas.

Economic conditions started to improve by 1909 - and that's when the steam laundries started to reap the benefits. Rand Steam Laundries had 13 branches along the reef by 1910, with 33 delivery vans and 200 white women and 100 black men at its headquarters at Richmond, Van Onselen says.

Between 1910 and 1911 three new laundries - the International, the Model and the New York Steam Laundry - were formed and by 1912 the steam laundries had control of the town's dirty washing. And the dirty war of price fixing and cartels made its presence felt.

But a broader international movement played a role too. Advertisements for washing machines began to appear in 1903, promising, "No more wash boys needed!" More and more working class white households were undertaking their domestic chores within the home.

The AmaWasha made a last stand by meeting with municipal officials, who only responded by raising rail rates. So the AmaWasha bypassed them and went to the government. Another meeting was held in the presence of the secretary for native affairs, W Windham, who assured the washermen that the council would "listen most carefully to their grievances". But nothing came of it.

"If the council did listen it certainly did not act, and shortly thereafter the Transvaal government officials concerned were absorbed into the Union's new civil service.

"The noose of segregation around the black laundrymen's necks was never loosened, and the 1910 meeting concluded with the remnants of the Zulu washermen's guild singing their way into economic oblivion to the strains of the national anthem."

By 1934, only 14 men still worked at the Klipspruit site and in 1953 the site was closed.

Van Onselen concludes that, "Zulu speakers were at least as quick as any other immigrant group on the early Witwatersrand to spot a new economic opportunity and exploit it". But as the town grew they became vulnerable when exposed to "capitalist competition" which invested in steam laundries. Their decline was "greatly hastened by the advent of urban segregation".

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.