Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Weddings are always big news. Especially when someone rich or famous is involved. Every marriage is preceded by some form of prior agreement, which is the subject matter of this article.

In the Western World the sight of a man kneeling before a woman, with an outstretched hand containing a small box will be instantly recognised as a proposal for marriage. “Rosemary, I love you with all my heart, will you marry me” and the much anticipated response “Yes, I will” usually signifies that the couple have entered into an arrangement known as “engagement”. The small box usually contains an engagement ring which will be worn on the ring-finger of the woman’s left hand as a signal to all and sundry of her “bespoken” status.

What many may be unaware of is that an engagement is actually a reciprocal contractual undertaking (a promise in fact) by the parties to be married to each other at some future unascertained date, and that failure to meet that commitment could have legal consequences in the form of damages for “breach of promise”.

That was the lesson learnt by Mr Rosenbaum in the case of Guggenheim v Rosenbaum 1961 (4) SA 21 (W).

In 1943 Mrs Guggenheim was divorced from her previous husband at Reno, Nevada although she was domiciled in the state of New York. Some time thereafter Mrs Guggenheim met Mr Rosenbaum, who was domiciled in South Africa but was visiting the United States. As these matters sometimes go, they fell in love and Mr Rosenbaum, while still in New York, asked Mrs Guggenheim to marry him. They agreed that the marriage would take place in South Africa. When Mr Rosenbaum returned to South Africa, Mrs Guggenheim followed close behind. In the process she gave up the flat she occupied, sold her motor vehicle and some of her furniture (storing the balance for the time being) and she gave up her employment.

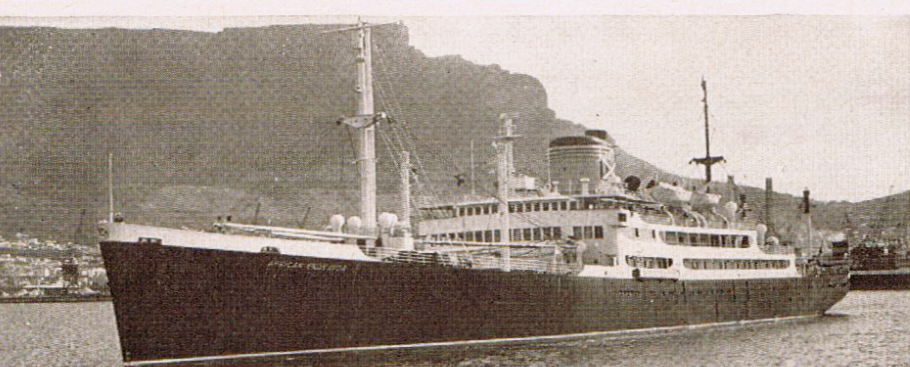

This was the era before intercontinental air travel became as prevalent as it is today and we can assume that Mrs Guggenheim travelled to South Africa on what was in those days called a “mail ship” because she arrived at Cape Town. Mr Rosenbaum was there to meet her. He once again professed his love for her, and repeated his promise to marry her in Johannesburg to which the couple eventually travelled. Once in Johannesburg, however, Mr Rosenbaum developed a severe case of “cold feet” and refused to marry Mrs Guggenheim, who was understandably more than a little put out by the turn of events.

A mail ship on the route from the US to South Africa

Mrs Guggenheim sued Mr Rosenbaum for damages for “breach of promise”. As an aside we can at this point note the essential difference between the formal response in a proposal to marry i.e. to be engaged, which is “I will” and in the actual marriage ceremony where the response is “I do”. Both result in a binding contract between the parties.

Mr Rosenbaum pleaded two “special” defences, namely:

- That Mrs Guggenheim’s divorce in the United States could not be recognised in terms of the South African law since she and her husband at the time were divorced in a state in which they were not domiciled. Mr Rosenbaum therefore argued that his promise to marry Mrs Guggenheim was consequently void as being contra bonos mores on the ground that Mrs Guggenheim was still legally married and that her marriage to Mr Rosenbaum would accordingly be bigamous.

- That the law of the state of New York had to be applied to the matter, and since New York did not provide for a plaintiff in the position of Mrs Guggenheim to recover damages for breach of promise, her claim should be rejected.

The Court rejected both of these defences, and instead directed its attention to the legal nature of the claim for damages, and to what actual damages Mrs Guggenheim was entitled to recover from Mr Rosenbaum.

The Johannesburg High Court where the case was heard (The Heritage Portal)

In the passages cited below Mrs Guggenheim will be referred to as the plaintiff and Mr Rosenbaum as the defendant.

In delivering the judgment of the Court, Trollip J stated the following with regard to the rules of South African law governing the award of damages for breach of promise:

In English law, breach of promise is regarded as being ‘attended with some of the special consequences of a personal wrong’ (Finlay v Chirney (1888) 20 QBD 494 at p 504), in consequence of which the plaintiff is presumed to have suffered damage as a result of the breach of promise itself. In nature and effect the damages are like those in libel actions......

The ordinary damages (i.e. other than specific monetary loss which must be specially claimed) are not measured by any fixed standard but are almost entirely in the discretion of the jury...Like libel too .... the damages which can be awarded are not necessarily compensatory but may also be of a ‘vindictive and uncertain kind...to punish the defendant in an exemplary manner’ (Finlay, supra et al). Consequently, it follows logically that the conduct of the parties may properly be considered in aggravation ...of damages, and I think that that conduct would most probably include the conduct of the defendant at the trial itself as in libel actions...

In pure Roman-Dutch Law the action for damages for breach of promise ‘remained rather undeveloped’ (Van den Heever on Breach of Promise, p37) because the usual remedy was an order for specific performance of the marriage, but where it did not lie it was to recover the plaintiff’s id quod interest (i.e. the actual and prospective loss) as in ordinary actions for damages for breach of contract (Van den Heever, ibid; McCalman v Thorne 1934 NPD 86; and Davel v Swanepoel 1954 (1) SA 383 (AD). Mere breach of promise itself did not give rise to an injuria which would have entitled the plaintiff to include a claim for damages for personal wrong in her action; if the breach, however, was committed in circumstances that also constituted injuria, then doubtless she could have included such a claim as a separate cause of action (cf Jockie v Meyer 945 AD 354).”

The learned Judge then pointed out that while the Roman-Dutch law differed from English law, early decisions of our Courts seemed to have followed English law implicitly without reference to or inquiry into Roman-Dutch law. The further debate on this distinction is fortunately for readers not required for the purposes of this article.

What we would rather focus on are two statements by eminent South African judges that Trollip J quotes with regard to the damages available to the plaintiff.

Firstly Melius de Villiers on Injuries at p 26 said:

A breach of contract is not, in its nature, an injury. The duty of fulfilling one’s contracts is one that does not arise from the respect due to the other parties thereto... So also, a breach of promise of marriage is not necessarily an injury. The favourable inclination of a man towards a woman may turn to aversion from numerous other causes than those which reflect upon her character, and there may be cases where a breach of promise of marriage may be occasioned by reasons which are strictly honourable. It might, however, be an injury when a person wilfully enters into an engagement to marry another which he does not intend keeping with the object of exposing that other to ridicule, or when he justifies his action by giving reasons for his conduct which are slanderous and untruthful.

Secondly Mr Justice van den Heever in his Breach of Promise (at p 30-31):

It is submitted that those decisions of our Courts which seem to imply that breach of promise must necessarily contain a delictual element are unconsciously based on English principles and have no support in Roman-Dutch Law. Unless a person who breaks off an engagement commits an actionable wrong ‘the feelings of the plaintiff and the moral suffering she has undergone’ are irrelevant to the question of damages... The notion that a woman necessarily loses social position or ‘face’ when an engagement is broken off in non-injurious circumstances seems to reflect the morals of a by-gone age when espousals constituted an inchoate marriage and repudiation was equivalent to malicious desertion.

In the case of Mrs Guggenheim (after dealing with ‘contractual’ elements of her claim) Trollip dealt with the delictual damages to be awarded to the plaintiff in the following terms:

The enquiry is first whether the defendant’s breach of promise was committed in a manner or in circumstances that constituted it injurious or contumelious. Unfortunately, probably owing to McCalman’s case, specific attention was not given to this aspect of the case either in evidence or argument. The reasons the defendant gave for refusing to implement his promise were not fully investigated in evidence or cross-examination but I think that on the balance of probabilities shown by all the evidence adduced, the defendant must have stated that he refused to marry the plaintiff at the final stage of their relationship because he had never promised to do so. In his attorney's letter dated 5th April 1960.... in answer to the plaintiff’s claim for damages, it was stated that the defendant denied that he had ever agreed to marry the plaintiff.

That was also the attitude that was taken up by the defendant in his pleadings and evidence in the case. I think, therefore, that it can be inferred that that was his attitude at all times relevant to this action. This is therefore not the kind of case where the defendant acknowledges the promise to marry but breaks the engagement in a sensible and non-contumelious manner in the interests of both parties... Here the defendant promised to marry the plaintiff; caused her to uproot herself from New York and come to South Africa in contemplation of the promised marriage; and thereafter cast her aside and refused to marry her, maintaining that he had not made any promise to marry her at all. I think that constitutes injurious or contumelious conduct for which the plaintiff is entitled to damages.

No specific evidence was however adduced to prove the extent of the injury to her feelings, her pride, or her reputation. She seemed to be more concerned during the trial with her contractual damages. But I think that it can be inferred that her feelings and pride were hurt at the time. However, although it is true that she is relatively unknown in Johannesburg and she intended returning to New York after the conclusion of the trial, she will suffer some humiliation on returning to her circle of friends in New York after all the elaborate steps she had taken to wind up her affairs there in order to leave for South Africa to get married.

On the other hand, she is a mature level-headed woman who has suffered somewhat similarly before when her marriage broke up, so the effect on her feelings and pride of the defendant’s breach is not likely to have been as severe as it would have been on a younger unsophisticated person.

I think in all the circumstances that the damages for the injuria should be R500 which I award. (It is of course important to remind oneself that R500 was worth substantially more in 1961 than it is today! For example a copy of De Rebus the official magazine of the attorney’s profession in 1960 makes special mention of a donation to the “widows and orphans fund” by a leading law firm in the amount of R 10,50!.)

It remains to be considered whether those damages should be increased by reason of the statements concerning the plaintiff made by or on behalf of the defendant at various times during the course of the trial. These statements were to the effect that the plaintiff was a blackmailer, a fabricator of evidence, a person who cunningly schemed to ensnare him into matrimony, that she drank to excess and surrendered her virtue easily. None of those statements were proved to be true on the evidence I heard; they are without any foundation at all.

Should they therefore inflate the damages awarded under this head? None of them had anything to do with the actual breach of promise itself. The defendant did not at the time of the breach, or in his pleadings, or in his evidence in the case, seek to justify his breach of promise because of the plaintiff’s character. I do not think that I need canvass the actual or possible reasons for the making of the statements, save to say that they had no direct connection with the actual breach of promise. Consequently I do not think that those statements can be used to inflate the delictual damages.... The above statements are prima facie defamatory of the plaintiff but they would constitute a separate and distinct injuria for which the plaintiff could sue separately if she is so minded.

And so the die was cast. A jilted promisee could claim for the actual patrimonial losses that were actually suffered as a result of the breach of the promise to marry, but would have a much harder time claiming damages for injured feelings.

But we like to add a word of a caution to those hot-blooded individuals contemplating following the practice of finding an exotic and often very public way of “staging” a proposal. Being called up on stage at the concert of a popular artist, or onto the field at half-time at a rugby or soccer international match or some other event witnessed by tens of thousands may seem a grand idea at the time (and may even endear the object of affection even further) - but watch out if a subsequent attack of a ’cold feet’ (for whatever reason) causes a retraction of the promise because that very publicity may increase the distress the jilted one experiences and you may end up paying a lot more than you contemplated!

This article forms part of a series on cases that shaped South African law. Click here to view other articles and here to pre-order the book. Should you require any further information or assistance regarding the topics we have covered you can contact us at: legaleagles@businessrestructuring.co.za.

Graeme Fraser (BA LLB LLM HDip Tax) and Veldra Fraser are corporate and commercial law consultants who operate under the Company Law Today brand (www.companylawtoday.co.za). We have a passionate interest in legal writing and in particular the collection of cases from South Africa and other jurisdictions. We have co-authored, self-published and marketed over 23 books since 2010 (and there are more in the pipeline). Graeme also wrote "Summit Vision" an account of the lessons he learned creating coordinating and completing the Millennium Big 5 Challenge in the year 2000 : Dusi Canoe Marathon, Midmar Mile Swim, Cape Argus Cycle, Comrades and an ascent to Uhuru Peak on Mt Kilimanjaro.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.