Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

[Originally published in mid 2015] Following a spate of attacks on colonial monuments around the country, paint was splattered on a post-apartheid statue on Gandhi Square in downtown Johannesburg. Eric Itzkin takes up the case of Gandhi and his bronze effigy.

For many people in South Africa and internationally, M.K. Gandhi represents a figure of great moral authority, an icon of peace. Introduced in 2003, the statue on Gandhi Square offers a tribute to Gandhi’s civil rights work in South Africa, and a means of recognizing and celebrating Johannesburg’s multi-cultural diversity.

Nelson Mandela has been among those who have paid homage to the Indian freedom fighter who began his struggles in South Africa. In an article dating from 1999, Mandela wrote:

Gandhi threatened the South African government during the first and second decades of our century as no other man did. He established the first anti-colonial political organization in the country, if not the world, founding the Natal Indian Congress in 1894. The African Peoples’ Organisation (APO) was established in 1902, and the ANC in 1912, so that both were witnesses to and highly influenced by Gandhi’s militant Satyagraha which began in 1907 and reached its climax in 1913 with the epic march of 5 000 workers indentured on the coal mines in Natal. That march evoked a massive response from the Indian women who in turn, provoked the Indian workers to come out on strike. That was the beginning of the marches to freedom and mass stay-away-from-work which came so characteristic of our freedom struggle in the apartheid era. Our Defiance Campaign too, followed very much the lines that Gandhi had set.

More recently, the statue of Gandhi was defaced with paint, and news media have carried commentary that the young Gandhi made racist statements during his stay in South Africa, and that he scorned Africans. This points to different views and perspectives on Gandhi’s legacy, which should be acknowledged.

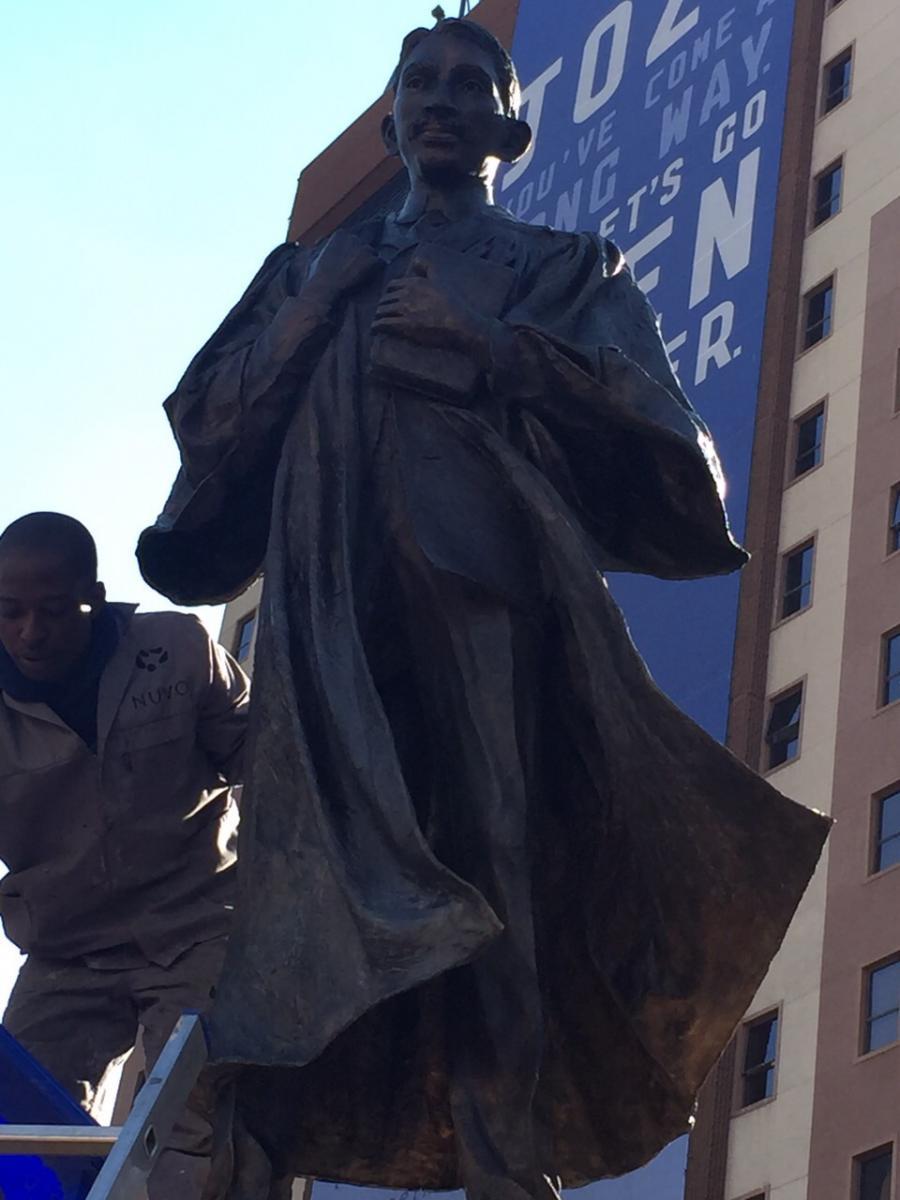

Cleaning the Gandhi Statue in June 2015 (City of Johannesburg)

Gandhi’s Political Evolution

Much of the discussion in newspapers and social media involves the selective use of quotes deployed to make particular arguments. This has prompted the South African struggle veteran Ela Gandhi to recently remark that, “If they consider him to be a racist, I can quote 100 passages from his work to show he hated racism and fought against all those evils”.

Nelson Mandela has also made the comment that, ““All in all, Gandhi must be forgiven those prejudices, and judged in the context and the circumstances. We are looking here at the young Gandhi, still to become the Mahatma, when he was without any human prejudice, save that in favour of truth and justice”.

Gandhi’s outlook developed and evolved over time, his political understanding grew, and he changed many of his views including his racial attitudes. Over the course of his stay in South Africa, Gandhi underwent personal and political change, showing a capacity to learn from experience and change his views.

Gandhi came to South Africa in 1893 as an inexperienced attorney aged twenty-four years old. His earliest statements about Africans show a great sense of social distance from them. Speaking at a public meeting in Bombay after three years in South Africa, Gandhi’s words were harsh:

Ours is one continuous struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.

His statement is a veritable catalogue of racial stereotypes common at the time among both white settlers and Indians, and the young Gandhi did not rise above the prevailing prejudices. Gandhi’s comments reflect also the intermediary position of Indians in South Africa’s social hierarchy during this period, set between the privileged whites and the mass of Africans. Efforts by the authorities to strip Indians of their limited rights fuelled fears on the part of many Indians of being cast down to the status of Africans.

Yet during this same period, Gandhi also asserted that Africans had as much right to the franchise in Natal as the whites or the Indians. In a letter published in the Times of Natal, 26 October 1894, Gandhi wrote:

The Indians do not regret that capable natives can exercise the franchise. They would regret it if it were otherwise. They (the Indians), however, assert that they too, if capable, should have the right. You, in your wisdom, would not allow the Indian or the native the precious privilege under any circumstances, because they have a dark skin.

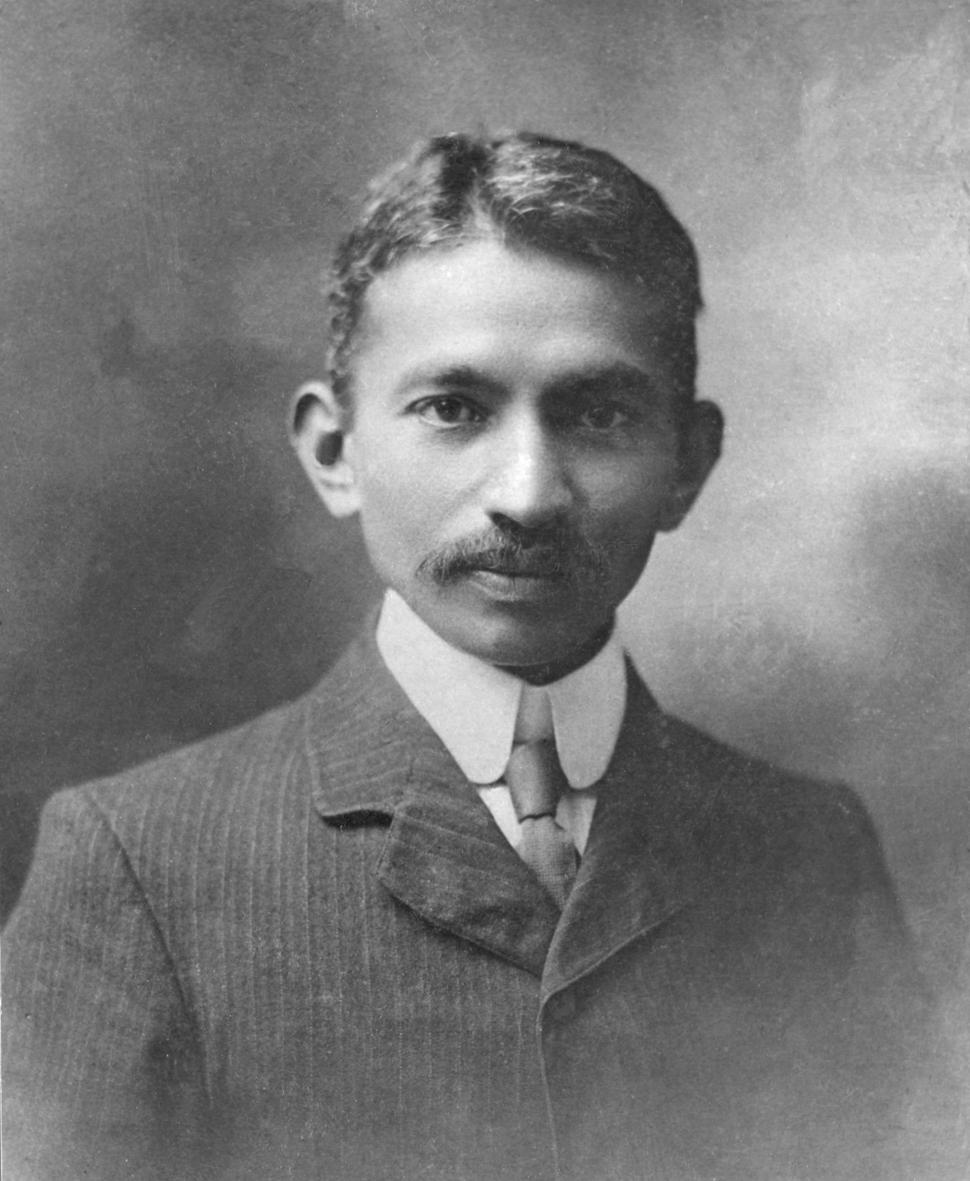

Gandhi 1906

In Gandhi’s early writings, there are derogatory references to kaffirs. Still today, such comments remain hurtful, offensive and are to Gandhi’s lasting shame.

However Gandhi’s newspaper in South Africa, Indian Opinion , kept the Indian community informed of major political events in the African community and shows that he was aware of their grievances and aspirations. In the journal Harijan (July 1, 1939) which Gandhi published in India, he later wrote of his close relations with Africans:

I yield to no one in my regard for the Zulus, the Bantus and the other races of South Africa. I used to enjoy close relations with many of them. I had the privilege of often advising them.

In Inanda, Kwazulu Natal, Gandhi established a settlement close by that of John Dube, who became the first President of the South African Native National Congress (later the ANC). The two leaders developed a relationship of mutual respect, and the first copies of Dube’s newspaper Ilanga lase Natal were printed on Gandhi’s printing press.

Dube was warmly introduced by Gandhi to readers of Indian Opinion in 1905:

Mr Dube, their leader, made a very impressive speech. This Mr Dube is a Negro of whom one should know. He has acquired through his own labours over 300 acres of land near Phoenix. There he imparts education to his brethren, teaching them various trades and crafts and preparing them for the battle of life. In the course of his eloquent speech Mr Dube said that the contempt with which the Natives were regarded was unjustified … For them there was no country other than South Africa and to deprive them of their rights over lands, etc., was like banishing them from their home.

John Dube

In his speech to the Young Mens’ Christian Association (YMCA), delivered in Johannesburg on 18 May 1908, Gandhi refuted the notion that differing civilisations could not co-exist, arguing that both the Asian and the African were assets to the British Empire and that differing cultures support each other:

We can hardly think of South Africa without the African races”, Gandhi told his audience, adding: “South Africa would probably be a howling wilderness without the Africans.

Now in his late 30s, Gandhi spoke at the YMCA of his vision of an inclusive, multi-racial society and polity in South Africa:

If we look into the future, is it not a heritage that we leave to posterity that all the different races commingle and produce a civilisation that perhaps the world has not yet seen.

The African races, Gandhi told his audience, “are entitled to justice, a fair field and no favour. Immediately you give that to them, you will find no difficulty.

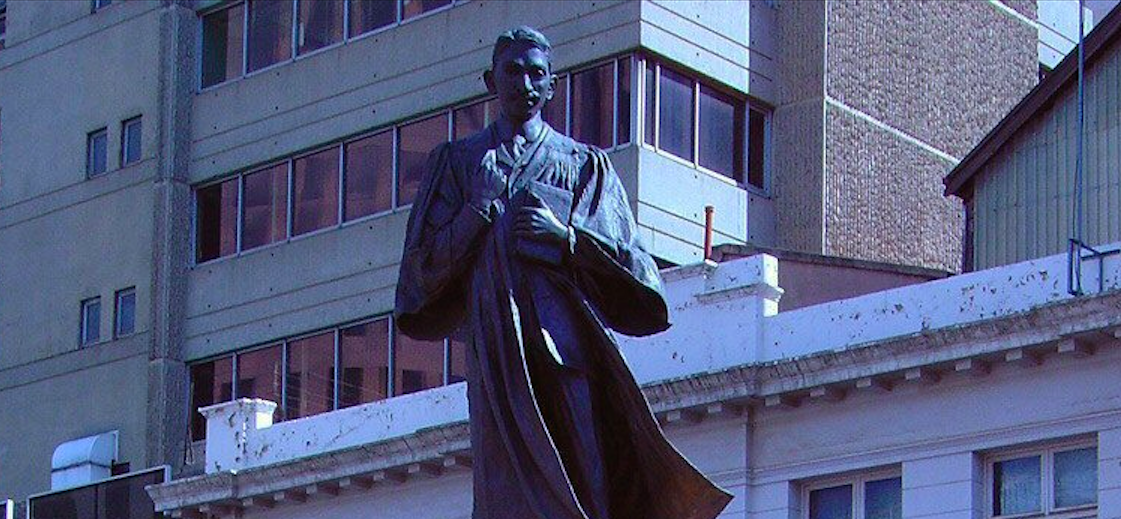

Another shot of the Gandhi Statue being repaired (CIty of Johannesburg)

Gandhi’s Legacy for National Liberation

To what extent did Gandhi’s conception of peaceful protest continue to influence popular struggles in South Africa after he left the country in July 1914? Gandhian traditions of non-violent protest undoubtedly became an enduring influence for the unfolding African liberation movement.

Up to the time of Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, his ideas and example failed to inspire a Satyagraha movement among the African majority in South Africa. But when resistance was revived by Indians in 1946, the great majority of whom were born in South Africa, it was to Gandhi’s techniques of civil disobedience that they turned. From 1946-48 Indians were engaged in a new passive resistance campaign, led by Dr Yusuf Dadoo in the Transvaal and Dr. G.M. Naiker in Natal, with some 2 000 volunteers going to jail in defiance of discriminatory laws.

The re-igniting of Indian passive resistance greatly impressed some of the younger African nationalists rising to prominence in the ANC Youth League (ANCYL). In his autobiography, Nelson Mandela describes the impact of the Indian protests of 1946-48 felt by himself and others in the ANCYL leadership:

The campaign was confined to the Indian community, and the participation of other groups was not encouraged. Even so, Dr. Xuma and other African leaders spoke at several meetings, and along with the Youth League gave full moral support to the struggle of the Indian people. The government crippled the rebellion with harsh laws and intimidation, but we in the Youth League and the ANC had witnessed the Indian people register an extraordinary protest against colour oppression in a way that Africans and the ANC had not. … The Indian campaign became a model for the type of protest that we in the Youth League were calling for.

The Indian Passive Resistance of 1946-48 was a source of inspiration for the Programme of Action adopted by the ANC in 1949. Introduced by the Youth League at the ANC’s December 1948 conference, the Programme of Action called for the use of civil disobedience, strikes and boycotts in the struggle against apartheid. Speaking years later, during the Treason Trial of 1956-1961, ANC leader Prof. Z.K. Matthews described the passive resistance of 1946 as the “immediate inspiration” for the decision of the African National Congress in 1949 to take up civil disobedience.

By the early 1950s passive resistance methods moved to the centre of the anti-apartheid demonstrations of the ANC. Non-violent protest spread among African activists in 1952 with the launch of the Defiance Campaign, the first mass anti-apartheid campaign, organised by the ANC and South African Indian Congress and modeled on pattern of non-violent civil disobedience set by Gandhi.

In this campaign, Africans entered into non-violent resistance inspired by the example of Satyagraha in South Africa and campaigns of civil disobedience headed by Gandhi in India. Led by Nelson Mandela as Volunteer-in-Chief, thousands of Africans joined Indians in volunteering to be arrested for breaking unjust laws. Resisters breached the pass laws, entered segregated locations without permission, and breached petty apartheid restrictions. Following the pattern set by Gandhi, there was not a single act of violence by the volunteers.

The Gandhian legacy speaks not only to the experience of South Africans of Indian origin, but has a wider national and international relevance. As a lasting tribute to the best elements of this tradition, the statue should remain forever and a day.

Eric Itzkin is the Deputy Director: Immovable Heritage in the City of Johannesburg

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.