Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

“I am inclined to think that the first experience of the Martini-Henrys will be such a surprise to the Zulus that they will not be formidable after the first effort.” Lord Chelmsford. 23 November 1878.

The Rifle

The outcome of the battle of Isandlwana, which took place on 22 January 1879 and resulted in the deaths of 1357 British and Colonial troops, shocked the “civilized” world. The British enjoyed overwhelming fire superiority – rifles, cannon and rockets, against spears. This meant that the Zulus had to close to about 30 yards before they could do much damage, whereas the British could kill them at far longer ranges.

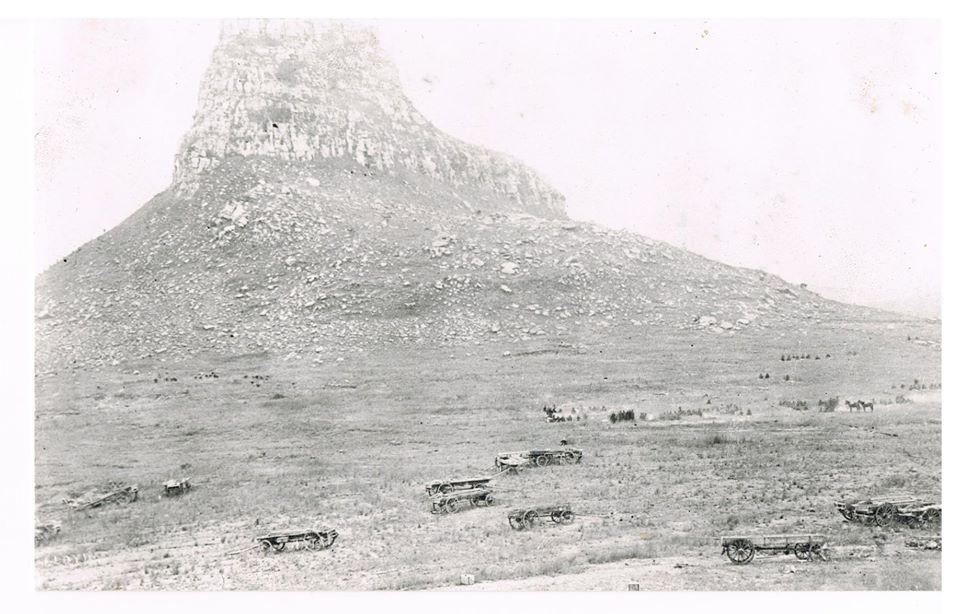

Isandlwana Hill (Talana Museum)

The standard British-issue rifle used at the battle was the Martini-Henry. This was a falling block, single shot breech loading rifle, which was a vast improvement from the old muzzle-loaders and even Snider conversions previously in use.

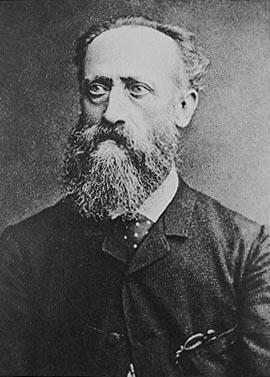

The forerunner of the Martini-Henry was the Peabody rifle, invented by Henry O. Peabody of Boston in 1862. The breech block was hinged at the rear and, when the lever beneath the stock was operated, moved so that the front of the block fell clear of the chamber, allowing space for a round to be slid over the block and into the breech. The weapon had an external hammer which had to be cocked manually, striking a firing pin in the breech-block when the trigger was pulled.

Henry O. Peabody (Candice Perry)

In Switzerland the Peabody system was modified by Frederick von Martini, who did away with the external hammer, allowing the weapon to be cocked automatically when the breech was opened. He also fitted an internal firing pin and spring inside the breech-block. This weapon was known as the Peabody-Martini, but the design was short-lived.

Friedrich von Martini (via Wikipedia)

The next step in the evolution of the rifle occurred when the British adopted the Martini action in April 1871, and allied it to a barrel rifling system designed by Alexander Henry of Edinburgh. The Henry system used a 7-groove polygonal rifling with one twist in 22 inches. A rifled barrel has a system of lands and grooves. The cartridge designation (,577/,450) refers to the distance between the grooves and lands respectively.

I have personally been lucky enough to shoot the Martini-Henry many hundreds of times. Our District Commissioner’s strong rooms in Rhodesia were always well stocked with old BSA Company weapons, as well as those held for safekeeping and from deceased estates. The rifle is a trifle heavy at just over 12 pounds, but well balanced, and points and shoots well. Although never exposed to sustained firing such as happened at Rorke’s Drift, for example, I have never experienced the reportedly savage recoil of the rifle; neither did I ever have a stoppage.

In short, from personal experience, it’s a great rifle to shoot.

Alexander Henry portrait in the Museum of Edinburgh (via Wikipedia)

Markings

Most markings were situated on the right side of the lock plate, consisting of the VRC monogram, the word “Enfield”, the date of manufacture and the Mark of the weapon – I, II, III or IV. Multitudinous markings are sometimes found on the butt.

The Cartridge

The Martini-Henry was designed for a Short Chamber Boxer-Henry ,577/,450 cartridge. Designed by Colonel Edward Mournier Boxer of the Woolwich Royal Arsenal in Kent, the cases were originally manufactured from thin sheets of brass coiled around a mandrel, which were then soldered onto an iron base. The case was designed to expand to fill the chamber on firing to form a seal and contracted slightly after firing to allow the empty case to be more easily extracted.

The coiled brass cases tended to be somewhat flimsy and extraction problems were known to occur. If the barrel was fouled or the cartridge extracted too violently, there were instances when the extractor claw tore the base off the remainder of the cartridge, causing fragments of the cartridge to remain in the chamber and barrel, thus creating a stoppage which had to be cleared before the next round could be loaded. This problem was later solved by manufacturing the cartridges from rolled brass, which were sturdier and did away with the soldered-on iron base.

Cartridges were initially filled with 85 grains of Curtis and Harvey Number 6 Black Powder and later with 85 grains of RFG 2 (Rifled, Fine Grain Number 2) powder. A 480 grain lead bullet was used, with a 3 mm beeswax wad behind it with a wood filler. The bullet doodled along at about 1300 feet/second. That notwithstanding, it had massive stopping power, especially if it hit bone.

Ballistically, the rifle had a theoretical maximum range of 1900 yards. Having shot Bisley in my time, a man-sized target is minute at only 800 yards, so even at that range the chances of a hit are remote. Ian Knight states that the maximum effective range was around 400 yards.

Mainly because the black powder propellant was relatively inefficient, the weapon had a bullet-drop of about 40 inches at 200 yards. It was therefore essential to know the exact range where the enemy was located, otherwise the bullet would literally “miss by a mile”. The placement of range markers was therefore one of the first tasks undertaken when taking up a defensive position.

It follows that one of the most important duties of the non-commissioned officers was therefore to ensure that sights were adjusted accordingly as the enemy closed in.

Martini-Henry cartridges (via Wikipedia)

The Ramrod

The rifle carried a ramrod secured in a sleeve under the barrel. A relic of the old muzzle loading days, the ramrod was supposed to be utilised to clear stoppages, remove fouling and for cleaning the barrel. They were apparently designed to fit flush with the end of the barrel, so as to appear uniform on parade.

Unfortunately, this desire for uniformity created an unforeseen problem. The length from the end of the barrel to the breech was 33 ¼ inches, but the ramrod was only 32 ¾ inches long. If, as has so often been claimed, the rolled brass cartridges tended to disintegrate in the chamber and cause a stoppage, one can appreciate that if this occurred, the unfortunate soldier’s ramrod would not have been quite long enough to reach right into the breech and push the fouled cartridge base out. He would therefore have been forced to dig out the bits and pieces with a clasp knife or some other instrument, a distressingly extended process when thousands of rapidly converging Zulus were in the vicinity.

The Bayonet

The Martini-Henry rifle was fitted with a Pattern 1876 Socket Bayonet. The bayonet was 25 inches long, with a 21 inch triangular blade, popularly known as “The Lunger”. It fitted over the foresight and was locked into place on the side of the barrel with a lock ring. A Martini-Henry rifle fitted with a bayonet gave, if nothing else, a superior “reach” compared to a Zulu stabbing spear.

Pattern 1876 Socket Bayonet (via Wiki Commons)

Three types of leather scabbards with brass fittings were used:

- Mark 1 - 3 rivets used to hold the long leaf spring which held the bayonet secure when it was in the scabbard.

- Mark 2 - 2 rivets.

- Mark 3 - 1 rivet. This type is the scarcest of them all.

Some sources state that the bayonets were made with inferior steel and sometimes tended to bend when being used. However, there is no real evidence of this, and each weapon would have been stress-tested before issue. One suspects that this yet another of the long list of excuses used to attempt to explain away the disaster at Isandlwana.

Ammunition Re-supply

See Grierson on page 140:

In battle every half-battalion is followed by an ammunition cart and a mule; the animal is placed between the supports, the cart behind the reserves; the other two carts of each battalion are combined to form the ammunition reserve of the brigade, and follow behind the second half of the brigade in charge of a mounted officer. In every company 1 non-commissioned officer and 2 – 3 privates are told off to bring and distribute the ammunition. Before the commencement of the engagement 50 cartridges are to be taken out of the ammunition cart for each man, so that each one is supplied with 150 cartridges. During battle cartridges must be sent to the front at every opportunity. In every cart there are a number of sacks (each containing 300 cartridges), two of which sacks can be brought up by each ammunition carrier. The carriers stop with their companies, and subsequent relief must come from the companies of the reserve. It is the duty of the non-commissioned officers to see that the cartridges are taken from the dead and wounded. Although the regulations proscribe that the ammunition should be brought to the front by men, yet the ammunition carts and mules must be pushed forward as much as possible. On ordinary ground the former must stand at a distance of 1000 yards; the latter at 500 yards from the line of skirmishers; in wooded or covered ground the distances are to be still less.

See also Ian Knight’s “The Sun Turned Black” on page 124:

Shortly after Mostyn and Cavaye’s companies had retreated to the bottom of the hill, Essex observed that they were “now getting short of ammunition, so I went to the camp to bring up a fresh supply. I got such men as were not engaged, bandsmen, cooks etc. to assist me, and sent them to the line under an officer, and I followed with more ammunition in a mule cart.

Smith-Dorrien, who could well have been “the officer” described by Essex, said in his memoirs that “I, having no particular duty to perform in camp ... had collected camp stragglers, such as artillerymen in charge of spare horses, officer’s servants, sick etc. and had taken them to the ammunition boxes, where we broke them open as fast as we could, and kept sending the packets out to the firing line”.

There is a bit of an anomaly here. Knight states that each soldier carried 70 rounds on his person, with 200 spare in the ammunition wagons. Grierson states that the soldiers carried 150 rounds, with sacks containing 300 rounds of ammunition in reserve. These were to be brought, two at a time, to the front by troops or by mule-cart. That notwithstanding, there is consensus. Once the carriers had gone forward, it was up to the reserve troops to assume the duty of carrying ammunition forward, which was precisely what Essex and Smith-Dorrien were doing.

Statistics from the battle of Kambula suggest that each soldier, somewhat surprisingly, fired an average of less than 40 rounds during that four-hour battle. That being the case, it would seem that most of the men at Isandlwana should have had enough ammunition on them to last through the main battle, which was over and done with in under two hours.

Even if they did not, the system of ammunition re-supply was obviously in place. There is therefore nothing to suggest that the troops ran out of ammunition. They may have run short, but not necessarily run out.

Tactics

See Grierson page 140:

In defence it is calculated that to occupy a fairly strong and partially entrenched position; there are required for every pace of ground 5 men of all arms, inclusive of reserves. The troops are grouped into three Lines (skirmishers, supports and reserves) as is done in delivering an attack. The first Line forms a line of skirmishers as close as possible, divided into sections, with local supports and reserves, and it also sends out men to occupy advanced posts, if any. The second Line protects the flanks with troops carefully placed under all available cover; it stands ready, jointly with other spare troops, to support the first Line, or to carry out counter-attacks. The third Line is drawn up in a position, whence it can assume the offensive with greatest effect; as soon as the attack is fully developed. The troops in the first Line must be kept well supplied with ammunition, and communication must be kept up by flag signalling.

See also Grierson page 170:

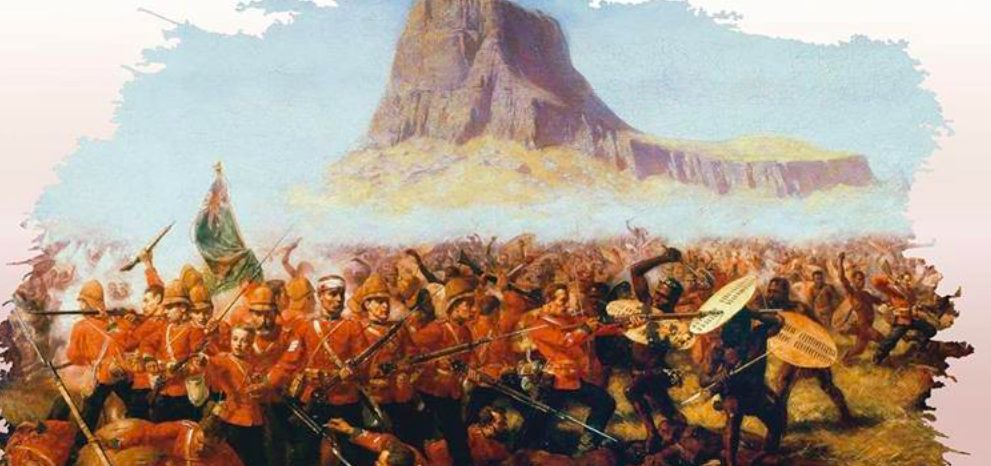

The usual deep formations of infantry are not advisable in war against savages; on the contrary, the front rank (line of riflemen) must be powerful enough to repulse all hostile assaults by their own strength. In the Zulu war a detachment was annihilated at Isandlwana, because the endeavour was made to resist an attack of the enemy in loose order. The infantry will mostly remain in close formation, and to advance steadily so as not to weary the men uselessly, and to maintain order. Special stress is to be made on fire discipline. The firing is exclusively by volleys and at short distances. What the savages dread most is a bayonet charge.

Volley firing would have been done by section, not en masse. There was therefore no requirement for individual marksmen to take pinpoint shots – the British relied on the weight of fire rather than the accuracy.

So, then, thus far we can see that the rifle was fine; the bayonet was fine, the ammunition was a man-stopper and the Brits had enough of it. The British purposely chose Isandlwana as a suitable defensive site. The Zulus approached from the front, in full view and uphill, giving the British reasonable time to prepare.

Painting of the Battle of Isandlwana (Ditsong Museum)

But the British were not in defensive mode; they were only too eager to give the Zulus a hiding before, as experience had taught them, natives would turn and run. So, instead of adopting a defensive position based on the high ground of either Isandlwana or Mahlabamkosi, they rushed out down the slope and made a major error in confronting the enemy in loose formation. This was a major contributing factor in ensuring that they snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.

Plus other contributing factors, such as the fragmentation of the British forces; the underestimation of the Zulu ferocity, resolve and determination; the failure to consolidate the camp; the lack of decent scouting; the various successful subterfuges employed by the Zulus ... the list goes on.

But perhaps there was another factor that also played a significant role in the defeat?

Smoke and Mirrors: The 60% eclipse of the sun during the battle. Would it have had any effect reducing visibility?

Much has been made of the eclipse of the sun that took place on the day of the battle, and the “surreal light” that it allegedly cast on the proceedings. It has become part of the superstitious folk-lore associated with this most inauspicious day for the British.

Yet I personally have witnessed three x 60% eclipses at Isandlwana in my 20 years on the battlefields, and I have to say that I wouldn’t have known that one was taking place without (a) being told so and (b) without dark glasses. On those three occasions it made no noticeable difference to the light.

Norman Leveridge of Talana Museum has done the technical research, and has concluded that, although there was indeed an eclipse on 22 January 1879, that particular eclipse would not have been visible at Isandlwana.

And it must be noted that the men at Rorke’s Drift, less than 20 miles away, did not report seeing an eclipse. They didn’t need an excuse – they were winning!!

So, what were the weather conditions like on the day? Hallam-Parr noted that “the morning became very hot, the sky perfectly clear, and only the faintest breath of wind”. Hamilton-Brown stated that “not a cloud was in the sky”.

So, then – hot, clear and no clouds, and no wind. Berkeley-Milne was able to observe the camp from 12 miles away up Silutshana, and misinterpreted the large black shadows that he saw as the column’s cattle. But by his observation one can conclude that there was little or no heat haze either.

Charles Aikenhead had the theory that it wasn’t the eclipse that was the problem; it was the smoke from thousands of cartridges hanging in the air that almost constituted a smoke-screen.

Ian Knight has also touched on the problem in “Go To Your God Like A Soldier” at page 182:

The main problem with volley firing was that, until the widespread use of cordite, black powder produced enormous quantities of smoke which tended to hang in the air on still days and obscure the target. This was not necessarily a problem in attack, when the troops were moving forward, but could cause difficulties in defensive formations. Several times during Zulu War battles it was necessary to cease firing for a few moments to allow the smoke to clear.

The point of this paper, then, is that the Zulus could possibly have been obscured from the British by a smoke-screen of their own making. Having been told that the wind wasn’t blowing too hard, if this was the case the rate of fire would decrease regularly and momentarily because the Zulu targets became indistinct in the smoke and the soldiers had to wait for it to dissipate.

The Zulus would not have suffered the same restraints. They were on the move, and would have outrun any smoke that their own rifles would have produced. But the British, firing from static positions, would have been enveloped in a murky cloud of gunsmoke.

Knight at page 137 quotes an eye-witness account of a Zulu warrior of the uKhandampemvu ibutho: “The tumult and the firing was wonderful. Every warrior shouted “Usutu” as he killed anyone, and the sun got very dark, like night, with the smoke”.

On page 138 he quotes another account of a warrior of the uNokhenke ibutho that, as the camp was being destroyed, “the sun turned black ... then we got into the camp, and there was a great deal of smoke and firing”.

These two accounts have been oft quoted to prove that the eclipse did indeed play a significant part in the overall gloominess of the camp’s last moments. But they miss the point – both make reference to the effect of the gun smoke, not the eclipse.

Secondly, if communication (as per Grierson) was supposed to take place via semaphore, that too would have been impossible if the field was covered in thick smoke. This would necessitate orders being conveyed by hand – a long, drawn out process when reaction speed would have been of the essence.

The conclusion to be drawn, then, is that the so-called “surreal light” allegedly attributed to the partial eclipse was, in fact, caused by the smoke produced by the black powder cartridges, and that the eclipse had very little if anything to do with it.

However, if this phenomenon became common knowledge, it would reveal an unforeseen weakness of the much-vaunted Martini-Henry - that the British could only fight from static positions when the wind was blowing! If this became common knowledge, there were serious ramifications which other indigenous foes throughout the Empire might note and use to their own advantage when it came their turn to oppose the Raj.

So the British blamed the lack of visibility on the eclipse instead.

The interesting question, of course, is could this have been another factor to add to the litany of errors which made a major contribution to the outcome of the battle?

Memorials at Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

References

- Grierson, Lieutenant Colonel James Moncrieff. “Scarlet into Khaki”. Lionel Leventhal, London. 1988.

- Hogg, Ian V. “Guns and How They Work”. Marshal and Cavendish. London 1979.

- Hogg, Ian V. “The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Firearms”. Hamlyn, Feltham, Kent. 1978.

- Knight, Ian. “Go To Your God Like a Soldier”. Greenhill Books, London. 1996.

- Knight, Ian. “The Sun Turned Black”. William Waterman Publications, Rivonia. 1992.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.