Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

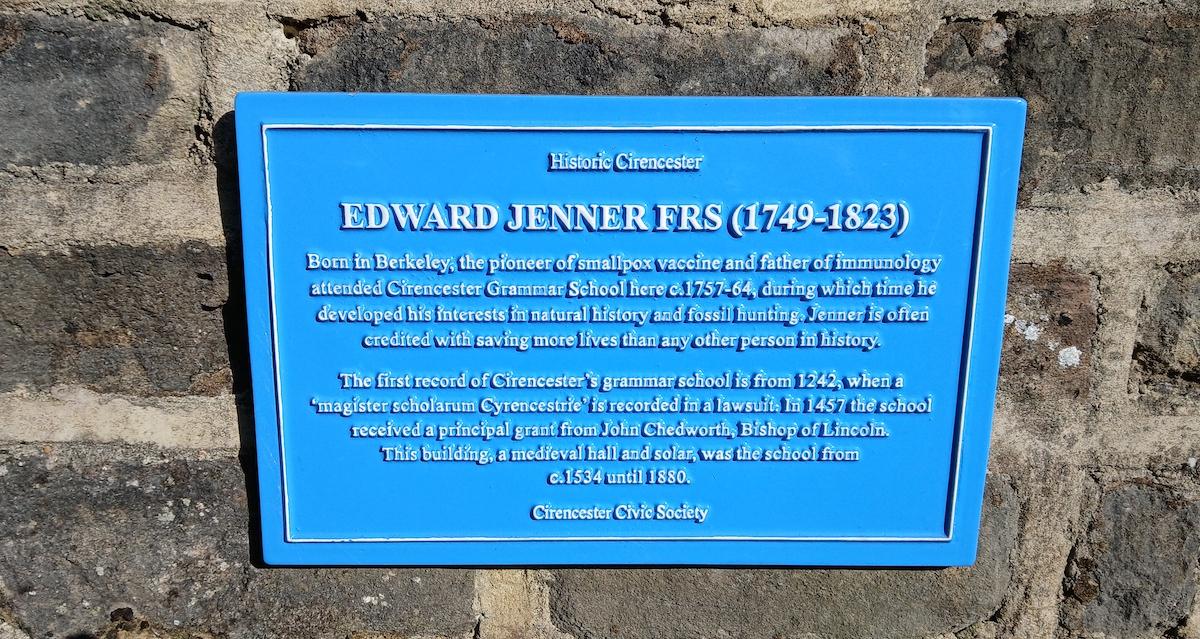

As many readers know, I love a blue plaque - and Cirencester, where I now live, has dozens of them. Recently, one plaque in particular caught my eye as I ambled about town. It claims that a man who studied here is "credited with saving more lives than any person in history." That’s a bold claim, and I wanted to find out more.

The modest building that once housed Cirencester Grammar School, it turns out, is where Edward Jenner was educated between 1757 and 1764. As many of us may remember from school, Jenner was the pioneer who developed the world’s first vaccine - for smallpox.

The Old School House (The Heritage Portal)

Born in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, in 1749, Jenner attended the grammar school as a boarding student during his teenage years. According to the plaque, the school operated from a medieval hall from around 1554 until 1880, with records dating back to 1242. During his time in Cirencester, Jenner developed interests that would later shape his scientific approach to medical observation.

After medical training in London, he returned to Gloucestershire and established his practice in Berkeley. In 1785, he purchased The Chantry, an early 18th-century house built on land once linked to a monastic community. From this base, Jenner pursued a wide range of interests beyond medicine, including natural history, fossil hunting, music, poetry - and even hot air ballooning.

The Chantry (Wikipedia)

At the time, smallpox was often a death sentence. Traditional prevention methods, including variolation (deliberate infection with smallpox material), carried serious risks. Jenner noticed that dairy workers who had caught cowpox - a much milder disease - seemed to be immune to smallpox. This led him to hypothesise that cowpox could offer protection against the deadlier virus.

On 14 May 1796, Jenner carried out his first vaccination experiment. He collected material from cowpox pustules on the hands of Sarah Nelmes, a local dairymaid who had caught the infection from a cow named Blossom. Using a lancet, he introduced this material into the arm of eight-year-old James Phipps, the son of his gardener.

Painting of Jenner and James Phipps (Wikipedia)

The boy developed mild symptoms and recovered. A few weeks later, Jenner deliberately inoculated him with smallpox material. James showed no signs of infection - suggesting that cowpox had indeed provided immunity.

Jenner continued his experiments, documenting cases and refining his method. He published his findings in 1798 in An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, laying the foundation for modern vaccination.

His success stemmed from careful observation and meticulous documentation. Jenner spent years gathering evidence and addressing scepticism. The Royal Society initially rejected his first paper, demanding more proof - which he then provided.

His approach blended scientific curiosity with empirical testing. Jenner’s background in natural history influenced his method: he recorded cases, tracked outcomes, and responded to critics with data.

Edward Jenner advising a farmer to vaccinate his family (Wikipedia)

His vaccination technique spread rapidly across Europe and beyond. Governments and medical communities adopted his method, leading to a dramatic reduction in smallpox deaths. In 1980, the World Health Organisation declared smallpox eradicated - the first human disease to be eliminated through vaccination.

The claim that Jenner "saved more lives than any other person in history" appears in numerous sources. Donald Henderson, Distinguished Service Professor at Johns Hopkins University and leader of the WHO’s smallpox eradication campaign, estimated that the disease killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Its eradication - and the many vaccination programmes that followed - have likely prevented countless more deaths. When considering the impact of vaccines on other diseases, the claim becomes genuinely compelling.

Portrait of Edward Jenner (Wikipedia)

Jenner’s former home in Berkeley is now Dr. Jenner’s House, Museum and Garden. It preserves artefacts from his life, including the horns of Blossom, the cow whose infection made history. It’s definitely on my list of places to visit.

One of the reasons I love blue plaques is that they can launch you on unexpected research adventures. I hadn’t thought much about Edward Jenner since school (maybe during the odd pub quiz) but stumbling across this plaque has led me down a rabbit hole of documentaries, podcasts and articles. It’s been a fascinating and thoroughly enjoyable journey.

James Ball is the Founder and Editor of The Heritage Portal. He lives in Cirencester and works for the National Trust.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.