Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 1811 Joseph de Maistre wrote that every nation gets the government it deserves. By extension then, it also get the heritage it merits, and as building after building in our city centres continue to fall before the demolisher’s hammer, many white South Africans have been left wondering exactly what they have done to warrant the destruction of so many of their memories. It is true that, in the 20th Century the world seemingly declared war upon its historical environments, but in South Africa, this phenomenon deserves special consideration.

To many, 1994 marked a turning point in our history, when we had the opportunity of leaving behind the horrors perpetuated by racism and Apartheid and embracing a bright new future, free from the guilt and recriminations of past events. Regrettably such an approach requires that many hard realities be put into abeyance, and it has not always been possible to ignore the bitter legacy that our ancestors have handed down to us.

Snaking queues to vote during the 1994 elections (Apartheid Museum)

The metaphorical flow of history is linear and does not have sharp corners or U-turns. Instead it moves inexorably through time, and while the lies and dark secrets of our colonial past may lie hidden for a while, eventually history will open them to the light of critical examination and the fresh air of open debate. Then, like suppurating sores, they are revealed for all to see, and while the process of healing is admittedly long and painful, only honest exposure can bring closure for the people concerned.

For others a more relevant marker in our racial history was set 46 years earlier, in 1948, when the Nationalist Party came to power. Most people who voted in that election are now dead or silenced by old age, allowing the blame for that criminal act to be safely transferred to that generation. This conveniently forgets that the colonial theft of land did not begin with Apartheid, but much earlier, in 1652, when the Khoi began to yield, under protest, to Dutch invaders. The assault upon the Xhosa nation began in 1781, and upon everyone else after 1836. The Dutch were in the forefront of such aggression but, for all their protestations, the English were never too far behind.

As a result between 1806 and 1906 at least 39 major battles and innumerable smaller skirmishes were fought between colonial armies and indigenous forces resisting the alienation of their ancestral lands. With a few notable exceptions, the victors were always white. This averages at approximately one major confrontation every 31 months, and when we consider the effect that similar bloody events at Sharpeville in 1960, Soweto in 1976, and Marikana in 2012 have had upon our national psyche, then one begins to understand the impact that repeated massacres must have had upon our ancestors only five or six generations removed. The German slaughter of 77,000 Herero men, women and children in 1904-8 in neighbouring Namibia must have resounded like a pistol shot throughout Southern Africa. The death through starvation of more than 70,000 Xhosa in 1856 must have been even worse. Time may eventually wipe out the specifics of a bloodbath, but the emotional trauma always lingers on.

Skirmish during the Xhosa Wars (Wikipedia)

There is much evidence to show that, even a hundred and fifty years ago, many white South Africans knew that their language and actions were wrong, even by the standards of their time, and that these were contrary to the Christian beliefs they professed to hold. Fearing retribution, for the God of their Bible is a vengeful god, in 1948 they sought the protection of a political party, that promised them the security of an armed laager. By 1990 it had become obvious that their war was a lost cause, and so for them the elections of 1994 became an act of atonement which may have reversed racist and discriminatory legislation but failed to wipe out the memory of 188 years of atrocities.

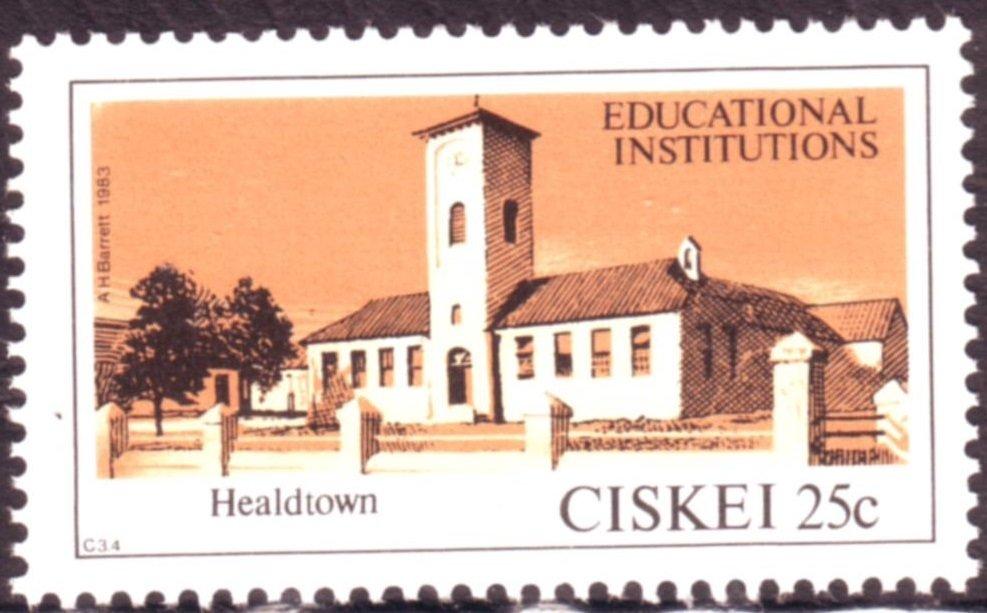

Whites were also at the delivery end of the stigma of racial discrimination, and the petty and constant humiliation that was inflicted upon men and women of colour on a daily basis. By European standards of the time many of these people were well educated, and belonged to a rising middle class educated at missionary technical schools such as St Mathews and Butterworth, and academic colleges such as Lovedale, Adams and Healdtown.

A stamp showing Healdtown

They were thus well-equipped to voice the grievances of their people. Yet for more than a century their patient and reasonable demands were demeaned, derided and ignored. Their leaders included men of stature such as John Jabavu, Sol Plaatje, John Bokwe and Tiyo Soga who, despite their age, intellect and gravitas were still referred to as “boy” by ignorant white buffoons, were expected to defer to a white child when walking on a city pavement, were liable to a beating if perceived to be “cheeky”, and were forced to use the kitchen door when calling at the home of a white family.

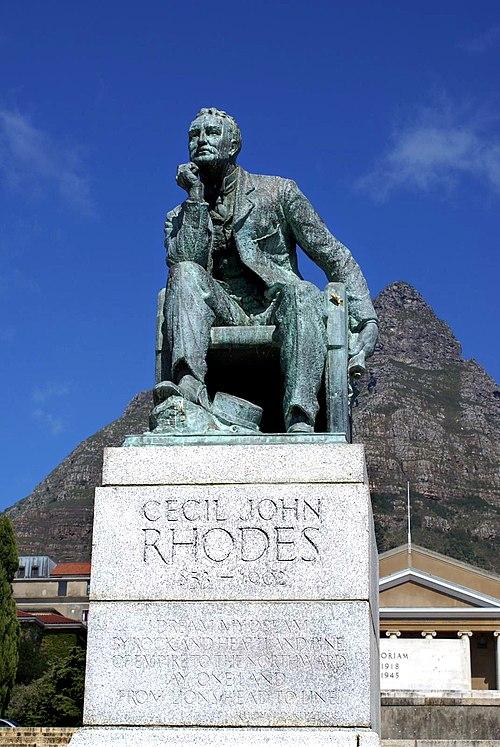

Today we recognise that words, actions and material objects have symbolic meaning, and buildings and statues have significance that extends beyond the scope of mere bricks and mortar. During the 1970s and 1980s the South African Government manipulated the work of the National Monuments Council to meet its own white supremacist political agenda, and its committees were controlled by members of the Afrikaner Broederbond. When, in 1987, the Post Office issued a set of definitive stamps bearing images of historical and civic architecture, it did so to celebrate the “establishment of the Western European civilization at the southern tip of Africa”.

Given the significance that white South Africans obviously attached to their colonial buildings, it was not unnatural that black South Africans should conversely perceive such architecture to be a symbol of their subjugation and humiliation at the hands of colonial “masters”.

In these terms, the antagonism shown by our students towards colonial symbols must be seen as a natural reaction against historical wrongs. Despite their inability to speak, the statues of tyrants still have the ability to remind us of times past, and bring back memories, both good and bad. And so do their buildings.

Rhodes Statue at UCT (Wikipedia)

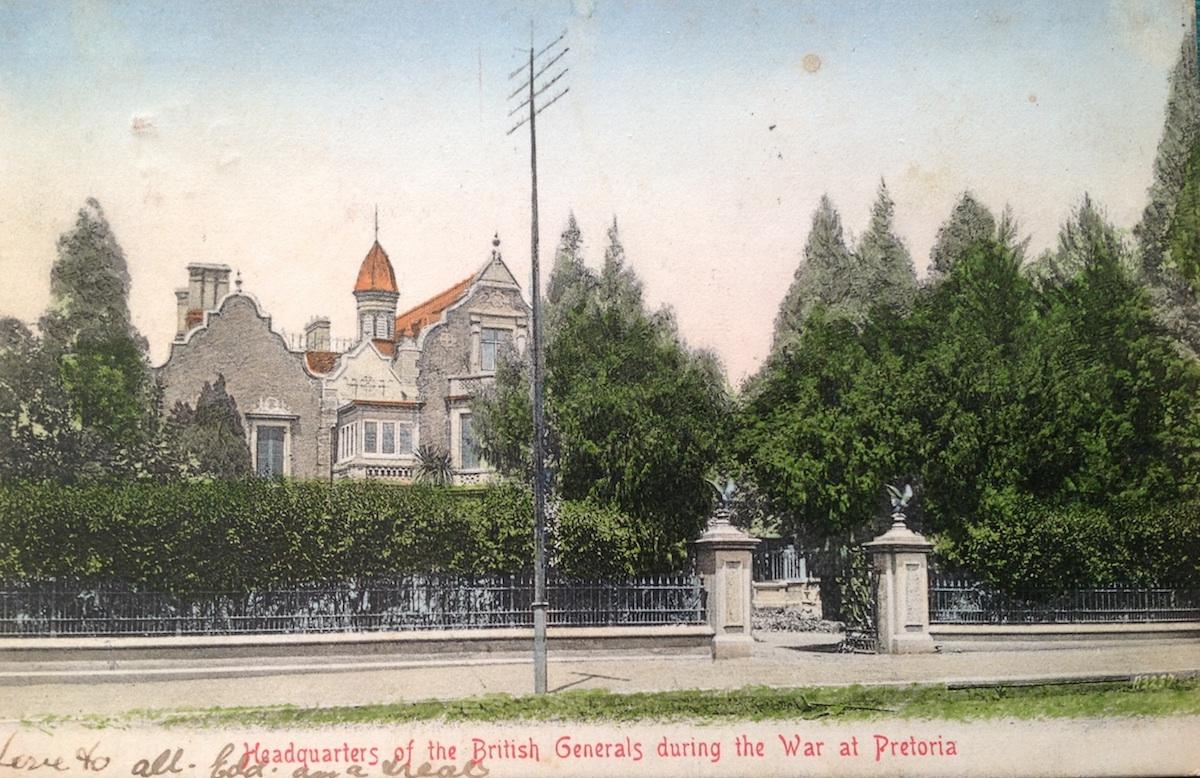

Strangely enough conservative Afrikaners, the very people for whom the Apartheid system was invented, hold a similar view of colonial buildings, and in 1990 some of them had no compunction in exploding a bomb in Melrose House, in Pretoria, simply because the Peace of Vereeniging had been concluded there in 1902.

Old postcard of Melrose House

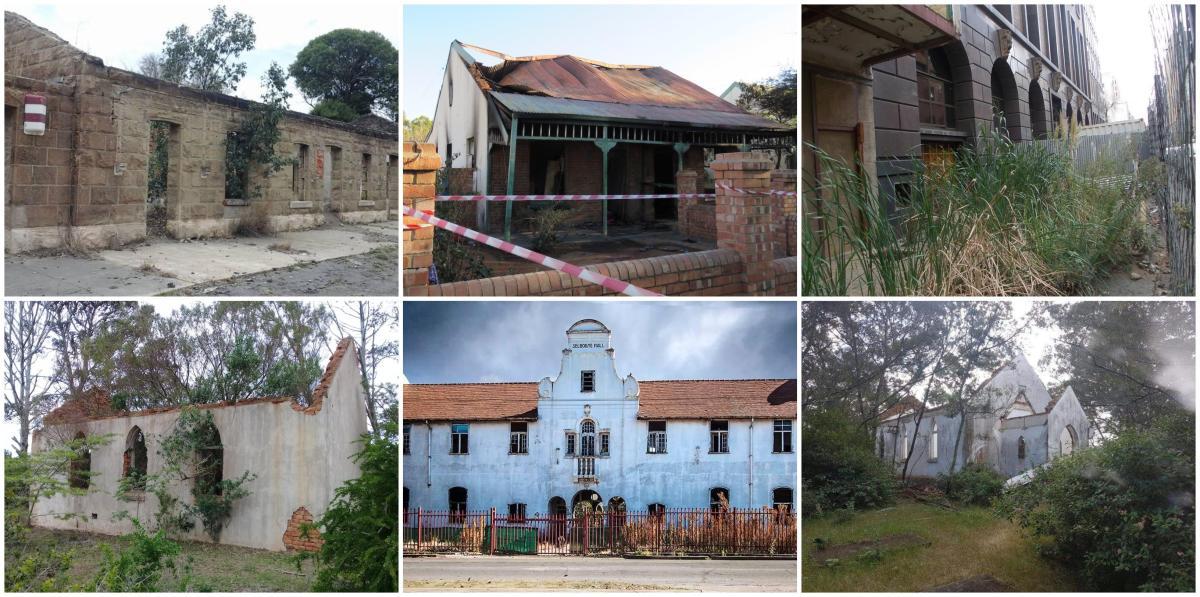

An inability to forego such atavistic hatreds and harness the historical built environment to more pragmatic uses does not bode well for its future, and while I acknowledge the sentiment and the right of South African citizens to remove the symbols of racist humiliations and national hurt, I do not understand where this road is going to lead us. Neither, I suspect, do the leaders of such a movement.

Franco Frescura - Professor and Honorary Research Associate, University of KwaZulu-Natal - frescuraf64@gmail.com

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.