Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Others tried and sorely failed to be the first to be able to travel by vehicle from Cape Town to Cairo.

Major Chaplin Court Treatt and his South African born wife, Stella, succeeded in doing so in 1926 for the first time ever, taking a humongous 16 months to do so.

Imagine the blood, sweat, tears and mosquitos that cover every exposed area on your body like a grey crust. There were mud swamps as wide as 20km that had to be crossed and they got lost in the desert. Christmas was spent in pouring rain under a leaking tent with one member who had a broken arm and another one with an almost deadly insect bite. Sometimes they were only able to cross rivers by dragging the vehicles under water over the bottom of the river.

Maybe they would have thought twice if they knew all this before they departed!

By the early twentieth century the British Empire was at its biggest ever. The route the Court Treatts chose was to stretch only over colonial territory, described as “all red” since maps of the time indicated British colonies coloured in red. Stella Court Treatt wrote in her book, Cape to Cairo, that was published in 1927: “The desirability of blazing a trail through British Africa was superior to every other consideration.” They later acknowledged that another route would have been shorter and easier.

As the crow flies, Cape Town is 7,241 km from Cairo. A current electronic route planner indicates that the road is 9 654 km in extent and that it would take you 141 hours to reach your destination!

The Court Treatts departed Cape Town on 23 September 1924 and after 16 months reached Cairo on 24 January 1926. They travelled 12,732 miles (20,490 km)! It is the same distance as London is from New Zealand. Two French expeditions at the same time attempted to travel from north to south, both completing the trek in exactly half the time.

This map was a supplement to Stella Court Treatt’s book, Cape to Cairo, and indicates their route over colonial territory that was coloured in red (pink).

Tried but failed

One man who dreamt to complete this endeavour, was Captain Raleigh Napier Kelsey, who led an expedition in 1913, travelling with an Argyll. Kelsey’s expedition came to a tragic end after he died near Kashitu in Zambia. A leopard attacked him, he fired a shot, but missed and pushed his fist in the animal’s mouth. After unspeakable agony, he passed away 46 days later. This was the end of his expedition, but the Argyll was for years afterwards the only motor vehicle used in that area.

Mayor Chaplin Court Treatt – generally known as “CT” – was described as the personification of a hero out of a Rider-Haggard novel with his double-barrelled surname, lean stature, resolute jawbone and ever-present pipe in his mouth. His wife wrote that he was taller than the proverbial 6 feet (1,82 m) and that his character was as strong as he was physically in size. In spite of this he was sweet-natured and friendly. He never lost his head and always stayed calm and composed in extremely difficult situations.

CT knew Africa. By the end of the First World War, then known as the Great War, he was a member of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and was stationed in Egypt when the armistice was announced.

After the war he remained on as an officer of the Royal Air Force (RAF). This was founded in 1918 when the RFC amalgamated with the Royal Naval Air Services. CT was a member of the team who was tasked to plot an air route from Cairo to Cape Town. He was in command of the group who was responsible for the part of route from Abercorn (now Mbala in Zambia) to Cape Town, a distance of about 2 000 mile (3 200 km).

This was completed in 1922. He remained in South Africa, where he met his wife, Stella, and they were married in 1923.

Stella Court Treatt, whose maiden name was Hinds, was born in South Africa. She grew up in the Magaliesberg with tales of their adventures as ivory hunters, told by her father and grandfather.

Stella was diminutive, an old-fashioned five feet two inches (1,57 m), and appeared still smaller next to her towering husband. She was recuperating after an operation when CT told her about his plans to attempt the trip from Cape Town to Cairo.

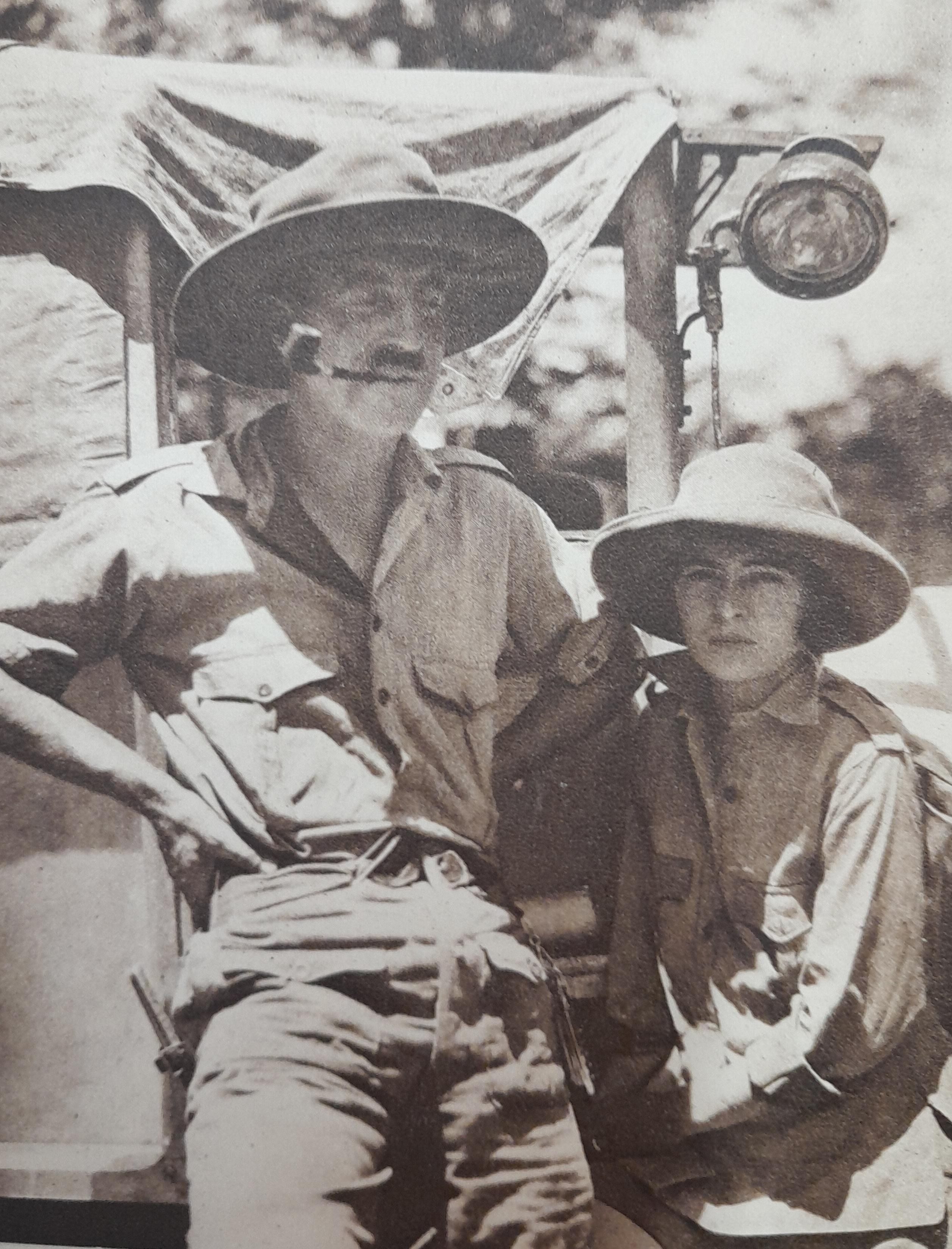

Major Chaplin Court Treatt and his wife, Stella, née Hinds, met in South Africa, got married in 1923 and the next year set out on the first successful expedition to travel by motor vehicle from Cape Town to Cairo. Photo: Cape to Cairo

Planning and Preparation

With letters of introduction and the blessing of General Jan Smuts, the Court Treatts arrived in England in March 1924. Doors opened and the planning of the expedition was underway. CT paid for it himself.

CT was introduced to Crossley vehicles during the War. Crossley were issued to all squadrons of the RFC to serve as light trucks (tenders) and staff cars. He was impressed with their ability to travel over rough terrain.

The two Crossley brothers were dedicated Christians and chose the Coptic cross as their emblem. They were also teetotallers and refused to sell their vehicles to anybody who had anything to do with the production of alcohol (Wikipedia)

Unlike the Kelsey expedition of 1913, who only had one vehicle, CT bought two Crossleys. He chose the adapted 25/30 chassis. It was specifically developed for the RFC and was fitted by Crossley with various bodies.

These two Crossleys were specifically adapted for the Cape to Cairo expedition (Crossley Motors)

Crossley Motors were situated in Manchester, England. The factory was established in 1904 and about 19 000 cars, 5 500 busses and 21 000 trucks and military vehicles were manufactured. After the factory was sold in 1947, it stayed in production until 1958.

The vehicles for the Africa expedition were modified by raising the suspension. Each could carry just more than a ton in payload. The body was painted a silver grey and the roofs were made out of aluminium. These could be removed, bolted together and served as a pontoon to carry the vehicles over rivers. Screens with mosquito netting that fitted over the windows and extra water tanks were installed.

The Crossleys roofs were designed to be able to be removed and used as a pontoon. Although made of aluminium, this was still too heavy and later discarded. (Crossley Motors)

It was decided to send provisions, food and spare parts ahead to 27 places on the route. To get this to their destination was in itself an expedition. Some could be sent by rail. In the Sudan, camels had to be used, but in some distantly situated areas, human carriers had to transport it over hundreds of kilometres. Some of those places were Johannesburg, Nyamandhlovu, about 40km northwest of Bulawayo in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, Mwaya Beach (Malawi), Nairobi and Khartoum.

Baggage was limited to the absolute minimum. One luxury was a gramophone. A sizeable stash of weapons and ammunition went with. This was not to defend the expedition, but to shoot meat for the pot.

Breakable items such as cameras had to be specially packed to survive the treacherous terrain. The proposal to make a film about the expedition, was that of the Canadian photographer Thomas Glover. CT promptly invited him to join the expedition as photographer and cinematographer.

Each member of the expedition had his or her designated tasks. Stella had to do a course in elementary medical care. She also had to mend all clothes and later said: “I hope never to darn another stocking in my life.”

After eight months of preparations, the Crossleys were loaded on the ship, the RMS Walmer Castle, accompanied by the Court Treatts and the rest of the company. The group arrived in a rainy Cape Town on 15 September 1924.

Departure in lovely sunshine

An old warehouse was rented where everything was prepared. Food, fuel and oil were bought and on 23 September the Crossleys departed Cape Town in lovely sunny weather.

Apart from the Court Treatts, the rest of the company included FC (Fred) Law, the correspondent of the Daily Express of London, and representatives of Crossley Motors: Captain FC Blunt and Mr McEleavey.

Blunt and McEleavey left the company in Johannesburg, after which Errol Hinds, Stella’s 16-year-old brother, joined them. Julius Mapata, a former employee of CT, travelled from here with them. Mapata, the son of a chieftain from Malawi, could, apart from English, speak 32 local dialects. In the Sudan, a man named Musa, was employed as translator, whose services to the team was invaluable. He remained with the expedition to the end.

The first evening was spent in Bainskloof, near Wellington. Somewhere in the Karoo, Stella decided that her thick, heavy coat was unnecessary and left it next to the road. The next day was presented back to her, neatly folded and packaged in brown paper! She later wrote: “I think Africa, from the Cape to Cairo is strewn with oddments from my personal kit.”

The first 1,000 km was completed in Kimberley on 2 October. Two days after their departure, one of the trucks broke down and they had to wait a week for the spare part to arrive from Johannesburg.

They stayed over in Johannesburg for a few days to rest and re-organize and departed on 25 October. A week later, on 2 November, they arrived at the Limpopo River.

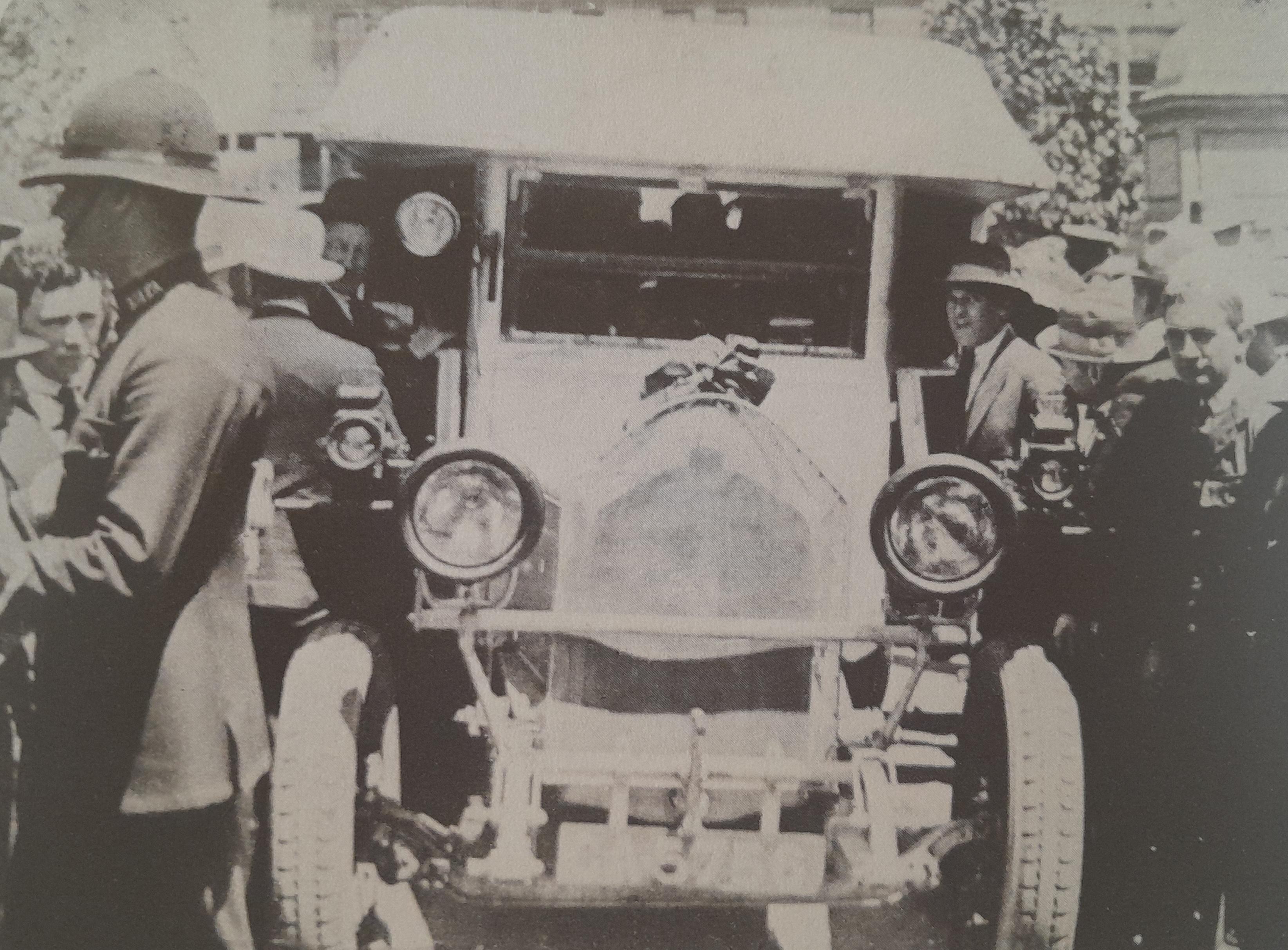

The Court Treatt expedition departs from Johannesburg (Cape to Cairo)

The rainy season arrived earlier than usual, but they reached the Great Zimbabwe Ruins on 12 November. They took a few days to repair clothes and camping equipment and to service the vehicles. After becoming stuck in the mud a few times, they arrived in Bulawayo on 25 November. Here the rear axle of one truck was rebuilt and a trailer was built.

By now it was raining cats and dogs and they prepared to attempt a part of the route that had never been traversed by car before. To lighten the load, they left some of the food behind. Afterwards their diet consisted of Bovril, Bully Beef, salt, coffee, flour and dried fruit.

The new trailer was left behind at Nyamandhlovu, as well as the aluminium roofs that were to serve as pontoons. The Kelsey expeditions of 1913 discarded a similar contraption in Paarl.

600 km takes four months

Today the road from Bulawayo to the Victoria Falls is 435km long and you can travel it in just more than seven hours. It took the Court Treatts four months to cover the distance! Just beyond Bulawayo the mud was determined to swallow up the vehicles. After the vehicles were dug out of the mud, they were only able to travel a few metres, before becoming stuck again and the process had to be repeated. They regarded it as a good day if they could advance 10 km! It rained incessantly and the air was so damp that, in spite of the heat, nothing dried out.

Camping was terrible. Christmas was celebrated with a warm meal, a cake, a plum pudding and champagne drank from tin mugs. This was, however, in the rain under a sopping wet tent. Stella wrote that the situation reminded her of what the soldiers experienced a few years before during the Great War in the trenches in France. “Can anything be more beastly than this Christmas Day”, Stella wrote.

A trip, supposedly to take a day, to the mining town, Wankie, took one month! Food stores became depleted and one tent was blown away. The young Errol Hinds proved himself to be a skilled assistant mechanic. He, however, broke his arm when he tried to hand start one of the trucks by cranking it. The crank handle flew back and his arm was in the way.

After the roof pontoons were discarded, all kinds of plans had to be made to cross rivers. This included pullies, pontoons and bridges that had to be cobbled together. If it was not for the muscle power of the local population and their oxen, the expedition would have come to a sorry ending. Stella’s book makes it appear that this labour was not always appreciated. Members of the local tribes, however, each received a penny for a day’s labour.

At the Gwayi railway station they camped out near the railway line. The train to the Victoria Falls steamed by and the wet, mud-covered team longingly stared at the passengers dining at tables covered with snowy white tablecloths.

Until now they stayed near the railway line, but after they crossed the Gwayi River, they decided to travel over higher ground. This meant that thickets had to be chopped open to make a road and their progress was lowered to walking speed.

On 25 April they reached Victoria Falls. Special permission had to be obtained to cross the Zambesi ravine over the railway bridge.

With the rainy season over, they were met by a new obstacle. Deep sand now lowered the Crossleys’ speed. The first day they only covered 29 km.

Meeting the French team

At Kafue they crossed paths with a French team that was on their own expedition to reach Cape Town from Algiers. The leader was Captain Delinqette and just like CT, he was a war veteran. He was accompanied by his wife, a mechanic and other members. With their Renault, that had six wheels (two on each side in front), they reached Cape Town on 5 July 1925 after travelling for eight months.

The Crossleys of the Court Treatt company meeting the Renault expedition (Early Motoring in South Africa)

Delinqette was not the first to cross Africa from north to south. In 1924 the Citroën Central Africa Expedition departed from Colomb-Béchar in Algeria and reached Cape Town eight months later on 26 July 1925. One source noted that the Court Treatts met the Citroën expedition, but the vehicle on the photo is clearly a Renault.

Early in July the Court Treatt company reached the southern shores of Lake Tanganyika. Here they turned east to travel through a swampy area. They had to cross about 200 rivers. Approximately 180 had bridges, made from tree stumps. Most of these had to be rebuilt before the Crossleys could attempt them.

At night the company was forced to keep to their tents, the only way to avoid the mosquitos. Their only entertainment was to listen to music on their gramophone. The daily dosages of quinine were kept up to prevent malaria.

On 24 July a steep incline almost caused a catastrophe. The Crossley at the back was not able to conquer the incline and started to run backwards. It was stopped by a tree before it could pick up much speed. After the vehicle was winched up, it was ascertained that damages include a broken axle and a hole in the radiator. The blacksmith capabilities of the team saw to it that it was repaired then and there the next day.

The company camped out for months in southern Tanzania to give Thomas Glover the opportunity to film the wildlife.

In Nairobi they met the Governor General and his wife. The journey to the border of the Sudan made rapid progress and they reached Mongala, 1 280 km further, in a mere eight days.

Ahead of them was the famous Sudd swamp. It is no misnomer that the name means “blockage” or “obstacle”. It is one of the largest wetlands in the world, but the expedition declined the suggestion to load the Crossleys on a steamboat to avoid the swamps. One of the upper reaches of the Nile River here, was, however crossed by steamboat.

The following 1,700km taxed the team almost to the end of their abilities. They departed on 25 October. With the assistance of the local Dinka tribe, the Crossleys were dragged through these stinking swamps in excessive heat battling swarms of mosquitos. The whole company became ill, but they carried on.

Under water over the river

The Crossleys were dragged under water through rivers numerous times. All the fluids were drained and all the openings were stopped with wooden blocks and wax. The steering wheel was tied with a little bit of give. The first time was at the Bahr el Gell River. Two ropes were tied to the front and fifty people were recruited to do the dragging. A float was tied to the ropes in case it broke – and it did.

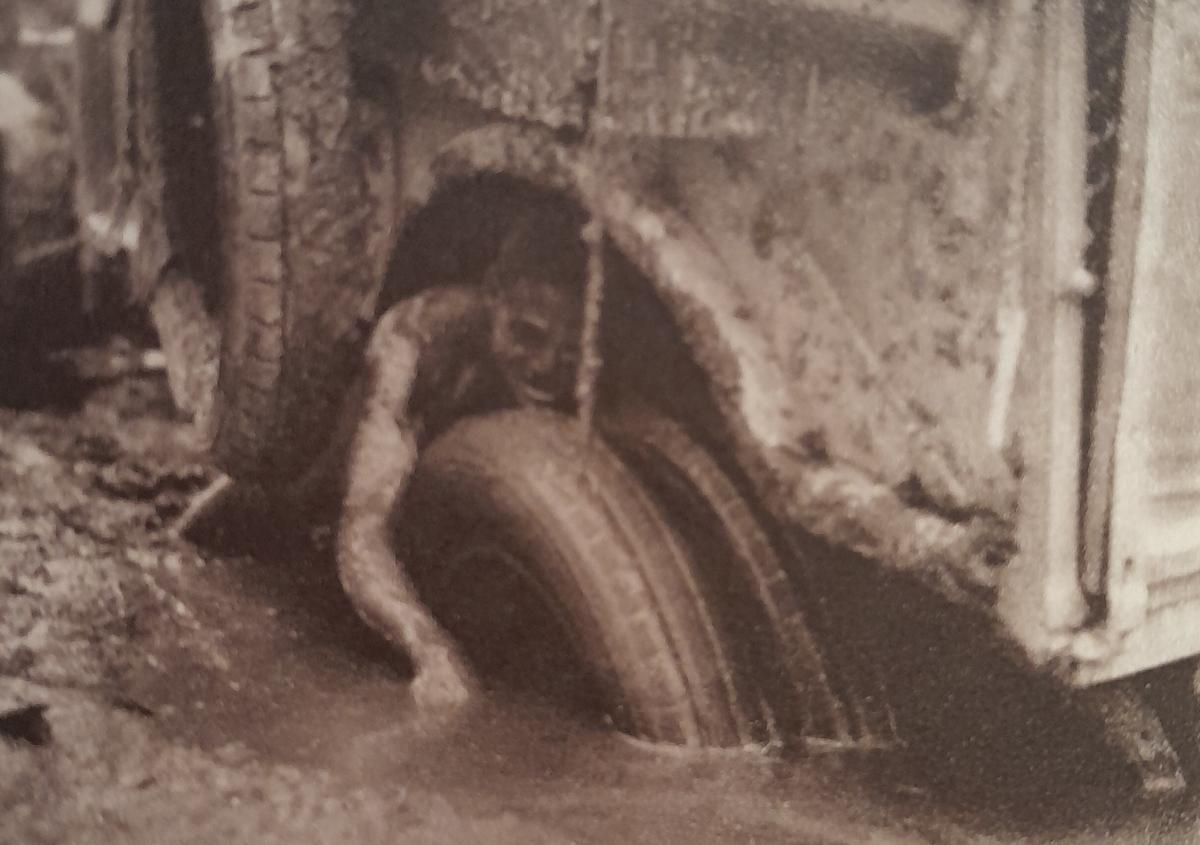

CT disappeared under water with the Crossley as they cross the Bahr el Gell River (Cape to Cairo)

CT remained on the Crossley as it was dragged. Once he and the vehicle disappeared completely under the water. He was able to grab the steering wheel with his hands and feet. Eventually the onlookers saw bubbles and the vehicle ascended slowly out of the water. Just when they thought the Crossley was through, it landed in a trough under the water! The only way was to dive in, scoop out the mud and an incline was made against which the vehicle could be dragged out.

In Wau, which they reached on 14 November, Musa joined him. He could speak Arabic, Swahili and a smattering of English. To communicate, CT gave the message to Julius in English. He translated it in Swahili to Musa, who often times had to find a Dinka that could speak Arabic, who could further translate it!

The next big river ahead of them was the Bahr el Arab, a tributary of the Nile. In places the swamps next to river were up to 13 km wide. There were no maps and a place to cross had to be found. On the way to a possible crossing, some of the young Dinkas set fire to grass to make a road. This got out of hand and the vehicles were almost destroyed.

On the other side of the river lived Arabs, who were not well-disposed towards the Dinka, to this day still a source of ethnic conflict in the area. Four Arabs were caught on the Dinka side of the river, but they were unwilling to indicate where they crossed the river. Eventually they were persuaded and showed where the crossing was.

The river was here about eight metres deep, but CT was of the opinion that a bridge could be built. There were no trees nearby and this had to be carried over a very large distance. On 5 December the bridge was ready and they reached the opposite bank, but still had to cross the swamp.

This was Arab territory and the Dinkas were unwilling to help. They were eventually persuaded with two antelope carcasses to drag the cars through the swamp on the Arab side of the river.

This was not the only river to cross and in places branches and leaves had to be packed on the sodden ground so that the vehicles could pass over. In other places elephants caused immense potholes in the roads. At one place each car broke a wheel in some of these potholes. They repaired one vehicle and departed with this to their next destination at El Obeid, about 64 km away. Spare parts were fetched from Khartoum and the second vehicle was repaired and fetched.

Second Christmas on the road

For their second Christmas on the expedition, they camped out in the desert. Memories of the previous, soggy Christmas were in everybody’s thoughts. Julius acquired a Christmas turkey in El Obeid and had it cooked.

The next destination was Khartoum and the expedition progressed swiftly. They travelled about 180 km per day and sometimes reached speeds up to 65 km/u. They were warned that it was impossible to travel from Haifa in the Sudan to Shella in Egypt. This rough terrain caused many flat wheels and breakages and they got completely lost. Food and water stores got dangerously low, but with luck a search-party from Aswan reached them.

A Felucca, a traditional Egyptian sailboat, transported the Crossleys over the Nile on a platform that was specifically installed to carry the vehicles.

The end

At Giza they were welcomed with flowers and by reporters and camera men. The road from there to Cairo was closed so they could travel on it. Next to it crowds of onlookers greeted them enthusiastically. This was 24 January 1926, the last day of the expedition.

CT and Stella in Cairo with other members of the team. Screenshot from the film Cape to Cairo.

Afterwards the Crossleys were loaded onto a ship in Alexandria to be taken to Marseilles. They travelled under their own steam to Calais where a ferry took them to England. Radio broadcasts, newspaper reports and parties followed.

The Crossleys were taken on a publicity roadshow that crossed the whole of Britain. At the same time Glover’s film about the expedition was shown. Only the last part of the film had been preserved for posterity. Click here to view.

What happened afterwards to the Crossleys is not known.

The Court Treatts came back to South Africa. Stella’s book about the expedition was published in 1927. She and her brother later made films. Stella and CT were divorced in 1935. CT passed away in Los Angeles in 1954. Stella married a doctor and lived for some time in India. She died in South Africa in 1976.

Errol Hinds and Stella collaborated to produce the film Stampede that was released in 1929. During the Second World War, he worked for the Army of the Union of South Africa as a photographer.

The Crossleys’ achievement left an indelible impression in South Africa. When the Prince of Wales visited the country in 1925, the government purchased three Crossleys for his use while here. The mayor of Johannesburg also acquired a Crossley as his official car.

A hundred years later the Court Treatt expedition is almost forgotten in South Africa, but their story, their adventures and their accomplishments should be remembered.

Main image: In spite of the double wheels that was especially fitted to the Crossley, it was mostly muscle power that made it possible to get the vehicles out of the mud. Stella’s commentary to this photo was: “stuck in a bog”. (Cape to Cairo)

About the author: Somewhere in her late teens Lennie realised that writing came easy to her and now, many decades later, she has written and co-written nine books on various aspects of the history of Potchefstroom. This is apart from various supplements and numerous articles, mostly published in the Potchefstroom Herald. Three of her books are available on amazon.com. One is a biography on Kenneth McArthur, Olympic gold medallist in the marathon of 1912. The other two are Afrikaans Christian novels. The supplement on the history of the Herald, at the time of its centenary in 2008, led to a Master’s degree in Communication Studies and one of the books, on NWU PUK Arts, led to a PhD in history. In the process of all this writing she has accumulated a large stash of information and photos on the history of Potchefstroom.

Sources:

- Barber, T. Cape to Cairo. Pell-Mell & Woodcote, July 2024.

- Court Treatt, S. Cape to Cairo, (GG Harrap, London, 1927).

- Johnston, RH, Early motoring in South Africa – a pictorial history.

- http://www.crossley-motors.org.uk/history/1920/court_treatt/cape_cairo_expedition_1.html

- https://www.britishpathe.com/asset/51847/

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.