Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Since its invention in 1839, photography has profoundly shaped modern society, becoming a central mode of everyday visual communication.

Photography emerged as part of a cluster of technical inventions and innovations (Wells, 1998), resulting in the camera, an instrument, a piece of hardware, having become omnipresent in our lives. Understanding the concept of photography, however, is no simple matter (Traub, Heller & Bell, 2006).

A philosophical reflection on photography and memory invites us into deep territory—where time, identity, reality, and technology intersect. This article is an exploration of this theme, reflecting on the blended philosophy, art theory, and human psychology.

In support of this article, mainly South African photographs in origin, from between the 1900s and 1970s, are included to support the philosophical narrative. In each of the photographs, a photographer is seen holding or using a camera.

The word camera originates from the Latin phrase camera obscura, meaning dark room or dark chamber, referring to the darkened space where early optical experiments projected inverted images through a small hole. This Latin term itself originates from the Greek word kamara (vaulted chamber). The term was shortened to just camera for the photographic device in the 18th century, linking the physical dark room to the mechanical box that captured images, eventually becoming the word for modern photographic equipment.

Historical selfie. 1930s black and white snapshot of a group of unknown young men. We would think that the concept of a selfie only relates to the use of a cell phone. In this very interesting composition, the young men found a way to capture an image of themselves by attaching yarn to a camera shutter release and then gently pulling the string once everyone was ready. Clearly visible is the string that the young man standing on the left would have pulled to produce this classic image.

A self-portrait by WD de F Collins taken in Egypt during World War 2 (1941)

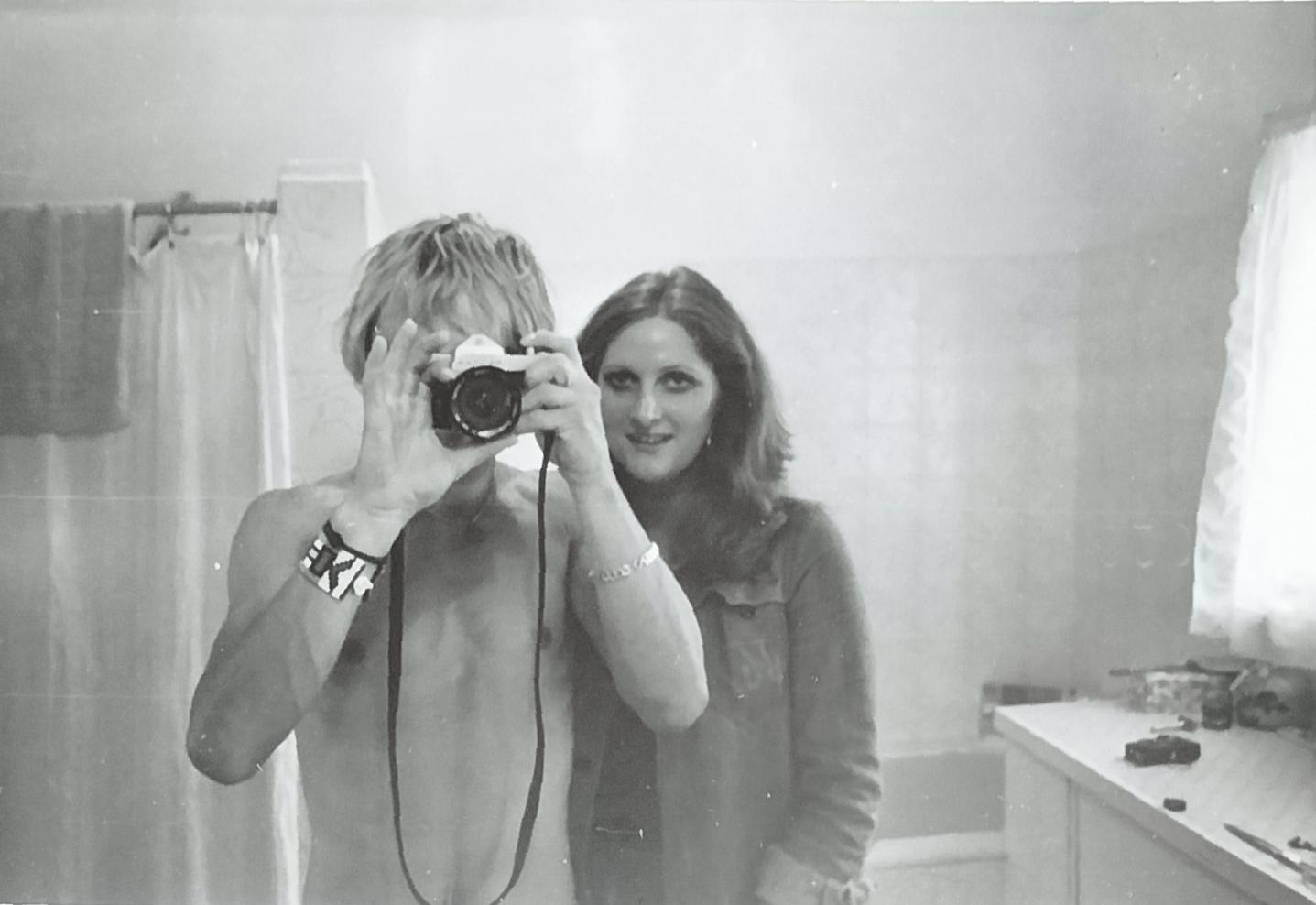

Reflection in the mirror using a 35mm camera – Unknown couple (circa early 1970s)

Self-portrait in the wheel cap of a Volkswagen, using a 35mm camera (circa 1960s)

Within a decade or two following the invention of photography, photography was used to chronicle wars, survey remote regions of the world and to make scientific observations. Life on the streets of cities became extensively recorded. Photographing the primitive, bizarre, barbaric, simply picturesque and culturally different from that of the photographer and viewer became appealing.

Downes (in Photography Annual 1963) made the following interesting observation:

Too many photographs? Too many cameras? Nonsense. Cameras are in the hands of a large part of the population. The camera is the people’s medium of creative expression. The more cameras, the more geniuses will be uncovered. The more cameras, the more photographs; the more photographs, the more pictures; the more pictures, the more great pictures... Cameras, and their operators, have therefore been producing the most precious documents in existence in that photography has become the medium most able to receive and fix the external, to collect and arrest, in the light of a unique moment, the mass and texture, tone and gesture of a particular place (Ventura in Photography Annual, 1963).

The camera can be defined as the optical tool used to record the multitudinous representations outside of us - anything and everything that exists beyond our corporeal bodies (The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, 2014).

Simplistically, what the camera does is to register upon film what is seen, followed by the decision made by the brain to press the button – also referred to as the decisive moment.

Which brings us to the question, why do we feel compelled to have a camera in hand and capture photographs?

Our need to capture photographs remains deeply rooted in psychology, culture, memory, and identity. The very presence of the camera transforms the scene; it intervenes in reality.

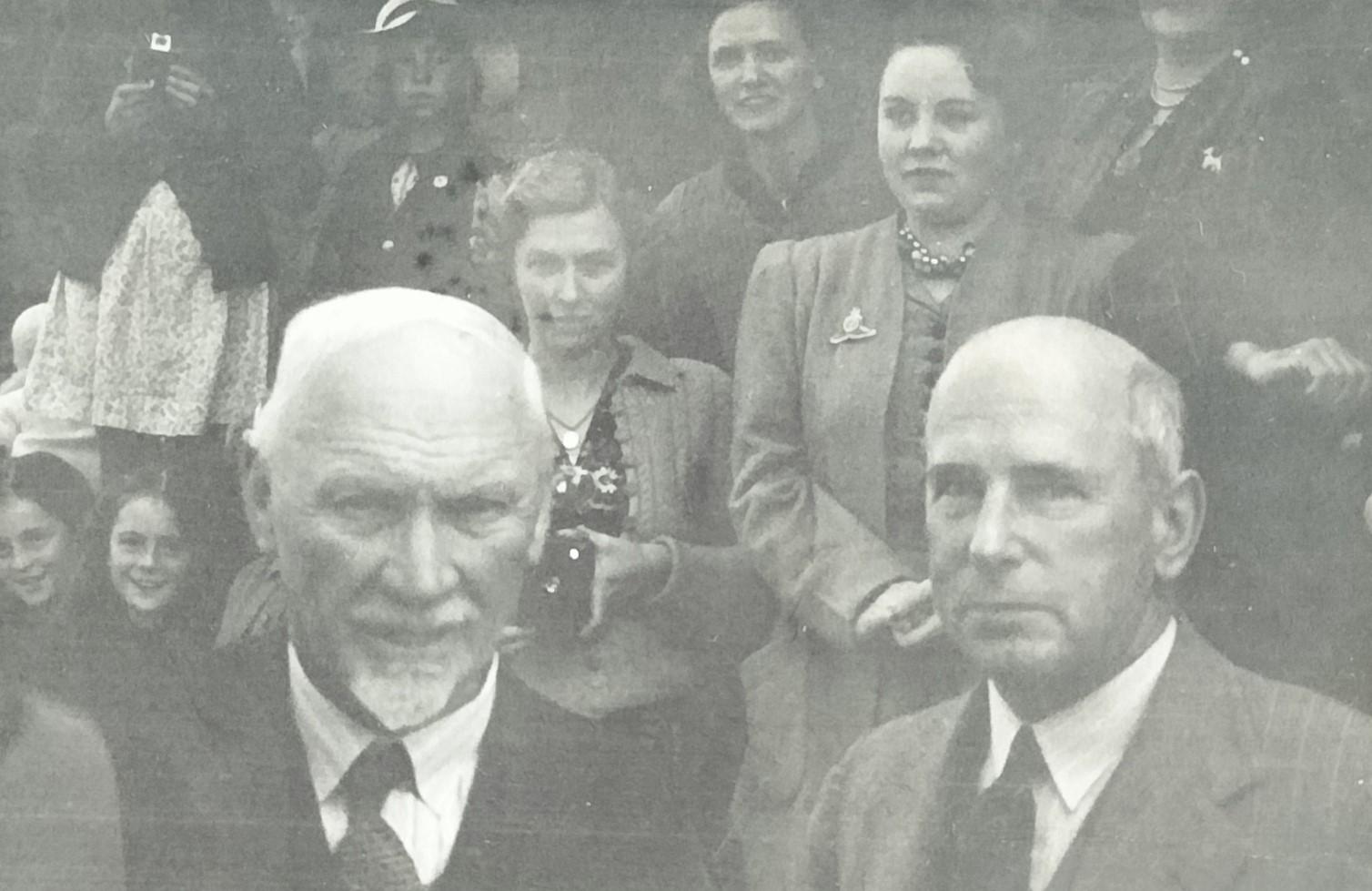

Two cameras in sight at an unknown gathering where Jan Smuts was present. Both cameras in the photograph are held by female photographers (circa 1940s)

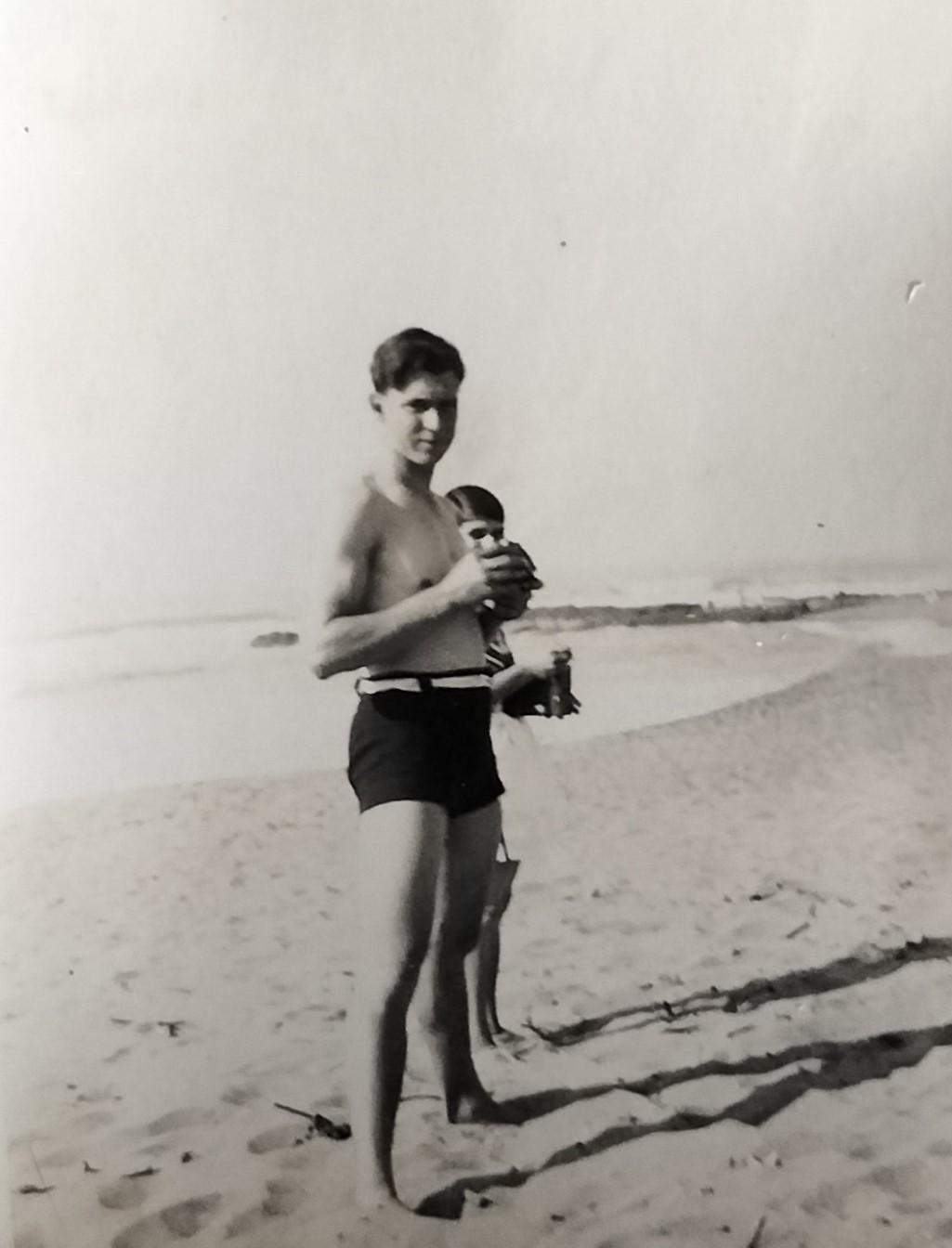

Photographers in the making on the beach. Both boys are holding box cameras (circa 1940s).

Although the camera is not visible, the lady on the right is standing in a typical early photographer position in the process of photographing the unknown wedding couple (circa 1950s).

The two ladies on the right are holding a box camera each, with the lady in the center seemingly attending to the camera of the lady standing on the right (circa 1930s).

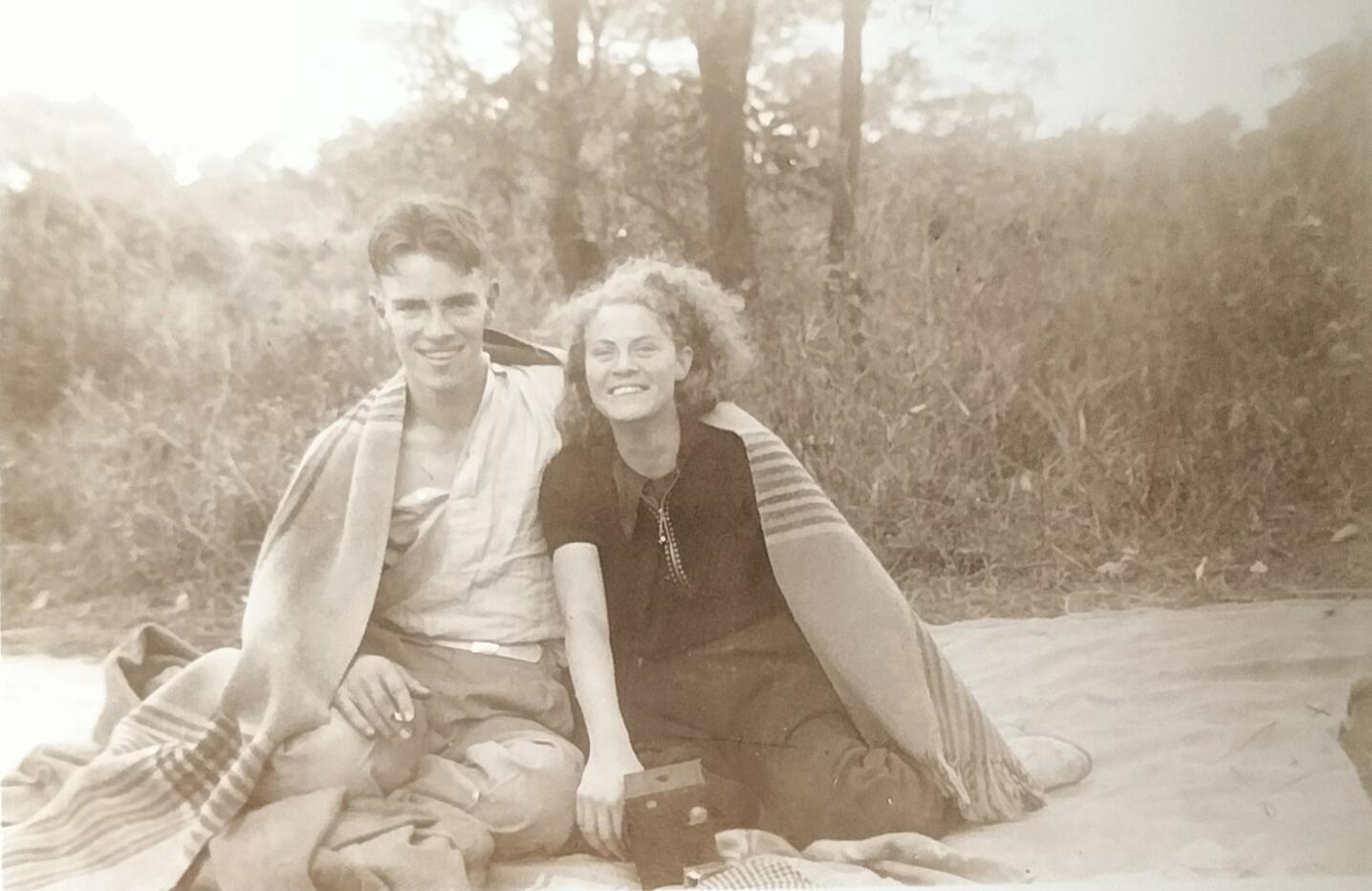

Tom and Joyce Clark out on a picnic in the bush (circa 1950s). In front of Joyce is a larger-format Kodak Box Camera.

A father attempting to capture a family photograph, but the little chap on the left on his tricycle is clearly uninterested. The father is holding a folding 35mm camera (circa, early 1960s).

Political figures at an opening ceremony/inauguration of some sort (circa late 1950s). This was seemingly an event that took place in Namibia (South West Africa then). The comical look of the young boy standing between the two adult men immediately attracts attention. In the background, two amateur photographers with their Kodak Instamatic cameras can be seen capturing some of the event.

A young lady standing next to an unknown river. She is holding a camera case. The case may contain her own camera or be the case of the camera used to capture the photograph (circa 1930s).

Photography is integral to the way we think. It informs every aspect of modern experience – our values, ideas, political views - in short, our ideas of ourselves and our world (Charlesworth in Traub et al, 2006).

Sontag (1979) observed that cameras did not simply make it possible to apprehend more by seeing; they changed seeing itself by fostering the idea of seeing for seeing’s sake.

Although Carl Jung did not write extensively about photography or the photograph, various of his concepts such as archetypes, the collective unconscious, individuation, and symbols are widely applicable to photography, viewing it as a powerful tool for self-discovery, exploring inner worlds, revealing universal patterns and bringing the unconscious to light, with images serving as windows to the soul or masks, highlighting the tension between inner reality and outer perception.

In essence, for Jungians, photography isn't just about capturing reality; it's about revealing deeper psychological truths, facilitating inner work, and connecting with universal human themes.

But perhaps the deeper question is not how we remember, but why. Do we take photographs to hold onto love? To shape identity? To prove existence?

The history of personal photography is more than a simple story of technological development. The desire to scan photographs of old friends has been expressed in a multitude of different ways where social and cultural structures are intertwined with the history of photographic techniques and practices, as are the interpretive meanings we bring to the pictures (Wells, 1998).

Photography is a universal language in that it evokes empathy, bridges distance and contributes to shared meaning. It allows people to share experiences across cultures, generations, and geographies. A photo can capture what words often cannot express.

Every photograph is a personal visual record of the aspect photographed – we all have different visual orientations and motivations as to what we view as “photographable.”

Brodovitch (in Traub et al, 2006) confirms that most snapshot, or amateur photographs, have their origin in our spontaneous and sincere way of seeing.

Photography is born out of a desire to preserve, but in doing so, it potentially emphasizes loss. In a more elementary way, photography is a way of saying: I was here. This happened. It mattered.

Although the camera, held by the female photographer on the left is hardly visible, it is clear that the subject matter is the baby with a grandmother. The father, to the left of the photographer, is assisting his wife to get the desired response from the little fellow (circa early 1960s).

Photographer at a school sporting event. The female photographer seems to be holding a Speed Graflex camera - a camera typically used by the media.

David with some SA soldier friends – March 1941. The lady has, what seems to be, a Kodak folding bellows camera on her lap.

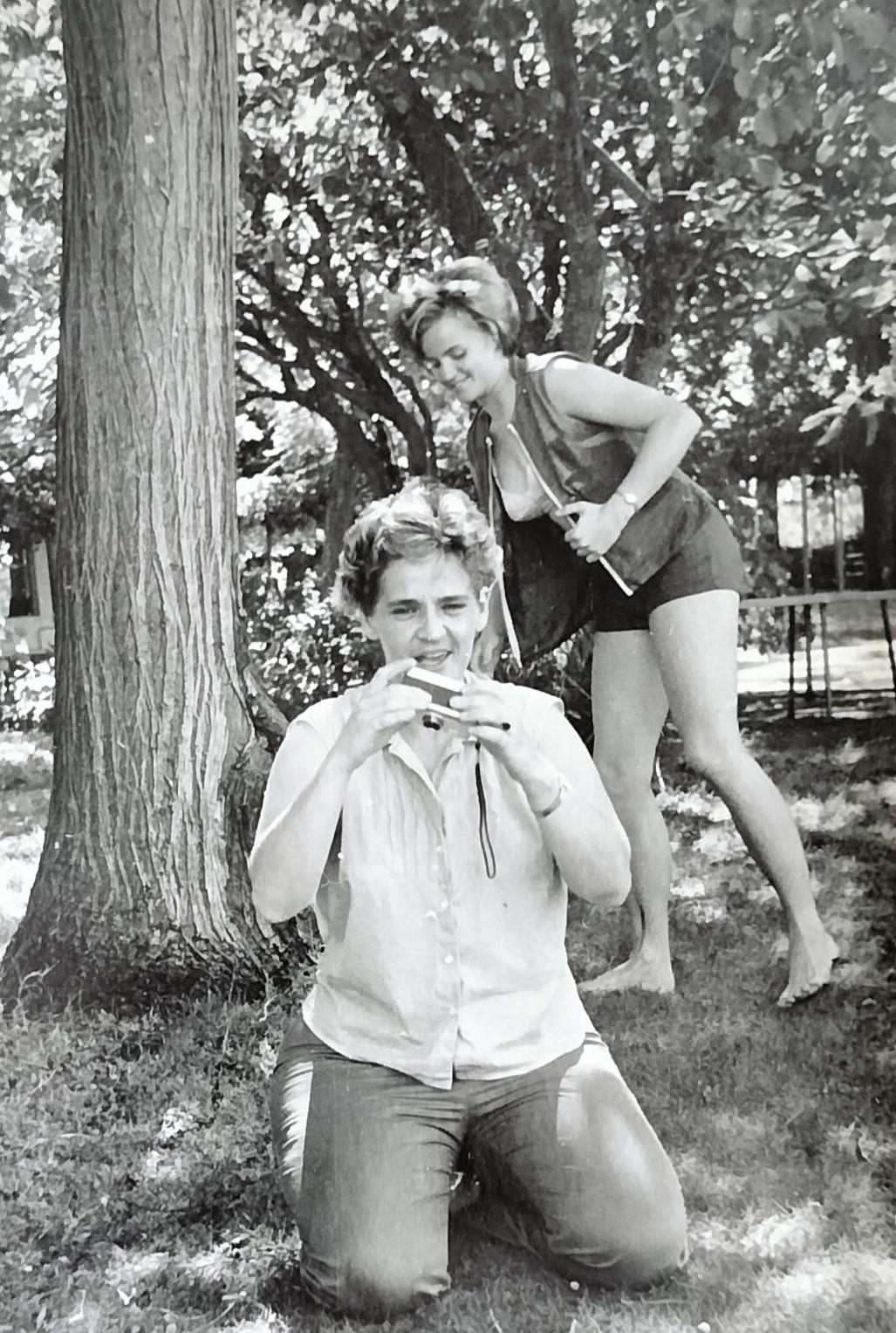

Not sure what is happening here. An upside-down Kodak Instamatic camera in the hand of the girl on her knees (circa 1970s).

One with a cigarette in hand and another with a 35mm camera in hand, being photographed at an unknown tourist spot (circa 1960s)

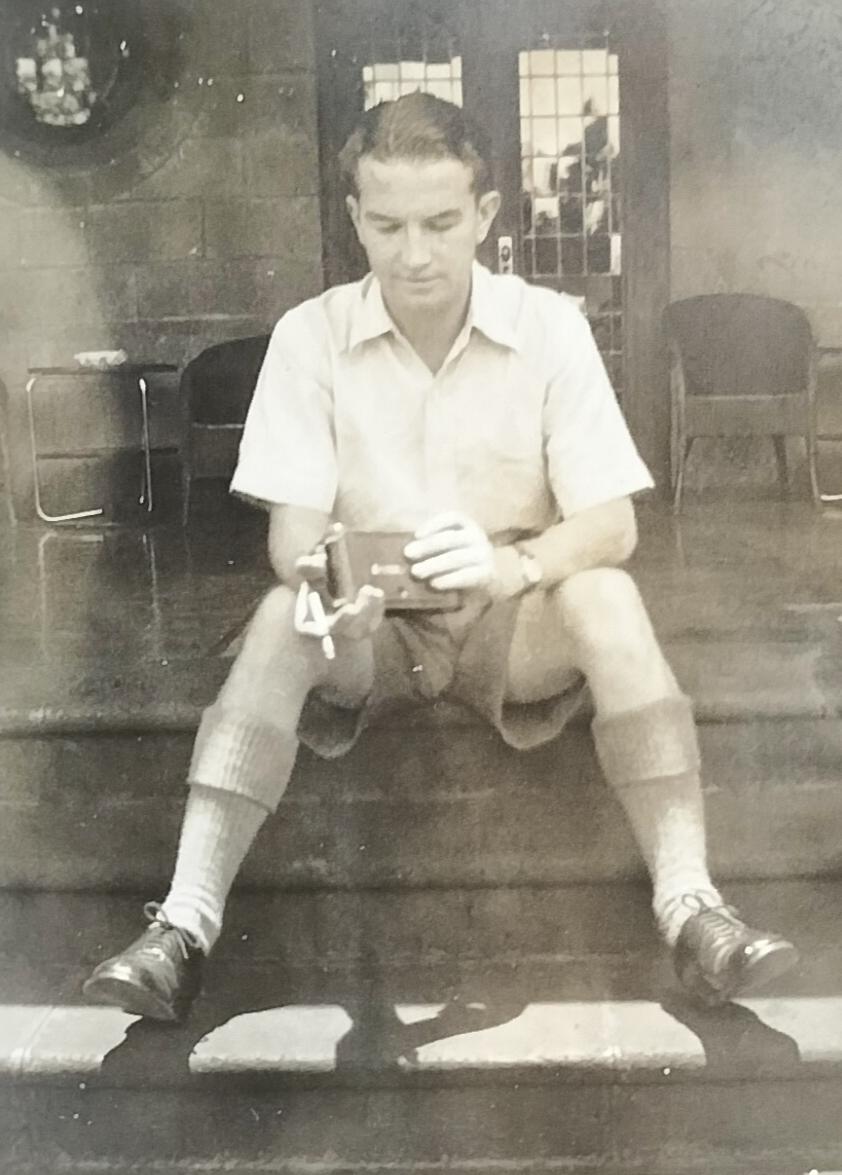

Mac on the steps of the Fairview Hotel holding a folding bellows camera (circa 1950s)

A photograph by East London-based Jack Ramsden. The photograph was taken at an important school event. Note the photographer’s spare camera, a Graflex press camera, in the foreground on the left.

Photographic excursion. Both the ladies on the right are holding high-end cameras. The man on the left could also be holding a camera? (circa 1950s)

Taking a photograph is also about framing reality—choosing what to include and what to exclude. It gives us a sense of control in a chaotic world. Sontag (2002) states:, To photograph something is to say: This matters.

Humans have an innate desire to remember and to hold onto moments that are fleeting. Photographs act as external memory aids, helping us relive important events, relationships, and feelings.

The act of taking a picture is a decision to notice, to record, and to preserve a subject, thereby designating it as significant or "worth looking at".

In some ways, photography creates a false sense of memory. When we look at a photograph, we often recall the photo more than the lived experience itself. We forget the day but remember the image. The photo becomes the memory.

This raises an abstract thought – have we been outsourcing our memories to images?

In the end, photography doesn’t just capture memory—it creates it, shapes it, and sometimes even replaces it.

In the digital age, we no longer take a few precious photos—we take thousands. But does this abundance deepen memory, or dilute it?

When every significant moment is photographed, does every single image of that moment feel meaningful?

Barthes (1981) stated that a photo is both a presence and an absence in that it shows what once was, but only as it looked, not as it was lived.

Thurmes (no date) aptly states: We take photos as a return ticket to a moment otherwise gone, or stated differently - Every photo is a reminder that a moment has passed and cannot be lived again.

This is the paradox: the more we try to hold onto time, the more aware we become of its passage. A photo, then, is not a moment captured—but a moment gone.

Sontag (2002) stated that: All photographs are memento mori. She continues: To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.

Ultimately, photography is deeply tied to death and mortality. A photo freezes someone in a moment they will never return to. It becomes, over time, an echo of someone no longer there.

The haunting power of old photographs—especially of people who have died—shows us that photography is as much about grief as it is about joy.

Photographing is therefore a response to the awareness that time passes, people change, and life ends. It’s a small rebellion against impermanence in that we photograph children growing up, weddings, vacations and funerals.

Photographs endure. They are passed down through generations. They become traces of a life once lived. Many people take photos so future generations will know they existed, what they loved, and how they lived.

Photos also help us tell stories - to others and to ourselves. In the digital age, we have come to construct narratives of who we are through visual media (social media profiles, family albums, etc.).

Humans, therefore, take photographs not just to see, but to remember, connect, express, and preserve. It’s not just about the image - it’s about what it means.

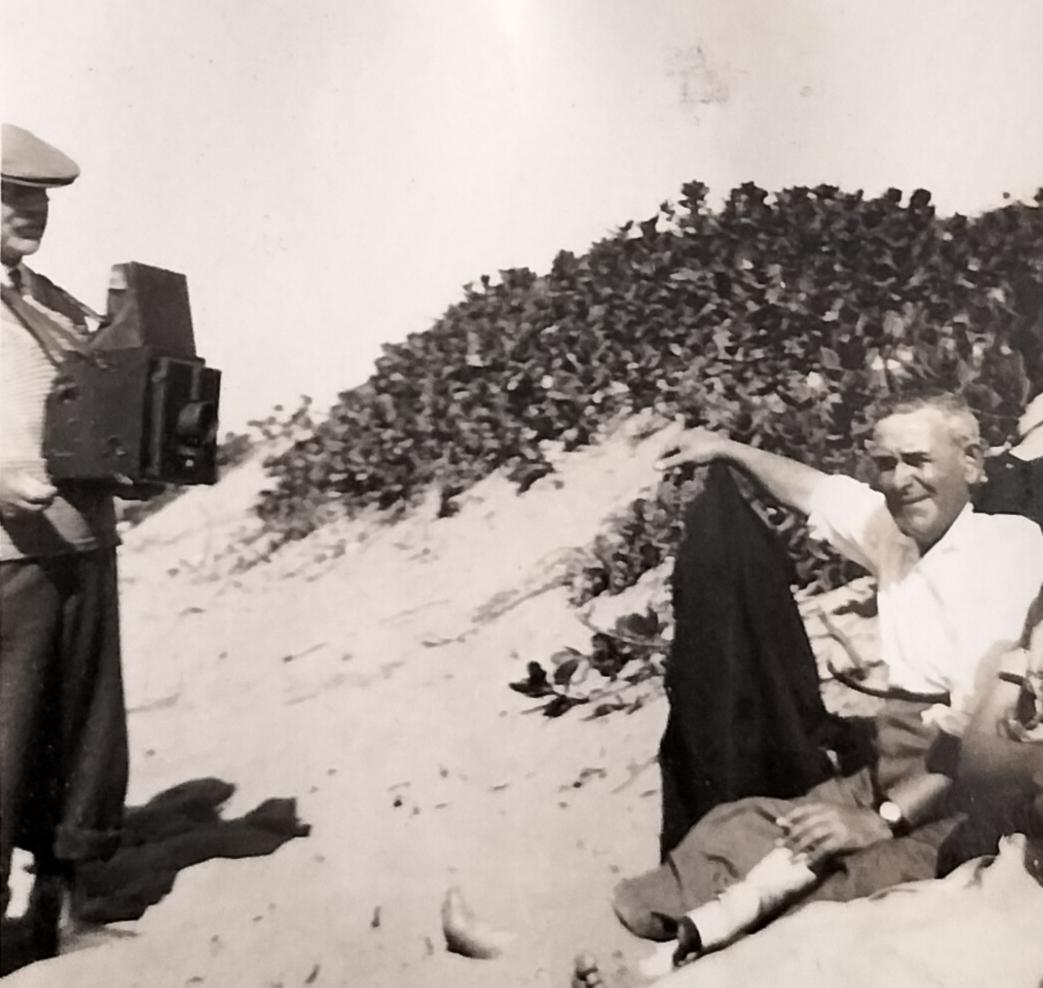

An unknown beach photographer with his large format camera engaging potential customers on the beach (circa 1930s)

A young girl practicing her photographic skills somewhere in Cape Town (circa 1960s)

Ria sitting on the steps leading to the lounge of the “Pretoria Castle” (June 1957), holding a Kodak Box camera

A photograph at an unknown event by the Port Elizabeth-based photographer WHB Wodehouse. The man in the white suit has a Graflex press camera in his hands. The photographer standing on his left is using a smaller-format press camera (circa 1940)

Posing with actors from a theatre production? The man standing on the left is holding a folding bellows camera (circa late 1940s)

Waiting to be snapped. The lady on the left seems to be holding a large-format camera of an unknown make (circa late 1930s, early 1940s)

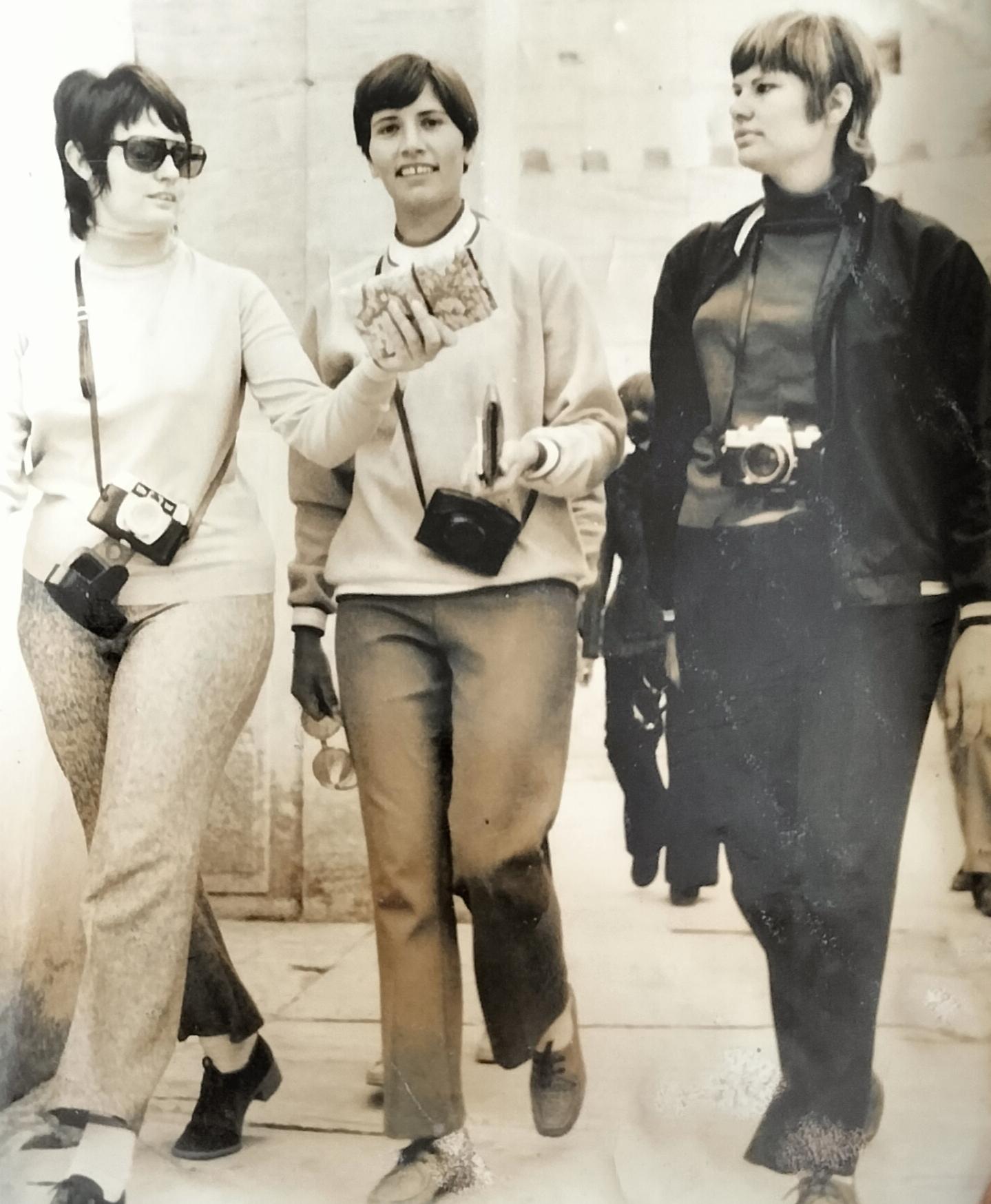

Three South Africans touring Greece, each of them with a camera for their own holiday snaps. This photograph was probably taken by a street photographer and sold to the ladies afterwards.

A young boy showing off his newly acquired plastic or Bakelite camera (circa 1950s)

Philosophically, photography also raises questions about who is looking and who is being seen. The act of taking a photo is a choice—what to include, what to exclude.

This is especially relevant in cultural and historical contexts, where photography has been used both to document truth and to construct propaganda.

To photograph is an act of taking versus making - the urge to photograph comes simply from a love of beauty, light, form, or composition – an aesthetic appreciation - an artistic impulse to freeze the poetry of a moment.

Ironically, when photographing, there is a tension between experiencing the present and documenting it for the future.

Sultan (in Traub et al, 2006) describes our drive to photograph what is most familiar to us – the family. Interestingly, Sultan continues by stating that photographing his father became a way of confronting his own confusion about what it is to be a man in his culture.

Crewdson (in Traub et al, 2006) states that photography is a conduit to almost everything in that it is a currency of our culture – we therefore need to understand how photography exists in our culture.

Flusser (in Traub et al, 2006) stated that human intentions through the eye can turn the photographic apparatus into a freeing device of expression.

Ozick (in Traub et al, 2006) reflects that taking pictures has nothing to do with art and less to do with reality – I’m blind to what intelligent people call “composition”. As for a camera as a machine – I know how to press down with my finger – the rest is thingamajig.

In my opinion, many of the South African snapshots, or black and white photographs, included in this article, fall into Ozick’s thingamajig approach.

Sandweiss (in Dyer, 2007) aptly summarises the capacity of photographs:

They evoke rather than tell, they suggest rather than explain, which makes them alluring material for historians or anthropologists or art historians who would pluck a single picture from a large collection and use it to narrate his or her own stories. But such stories may or may not have anything to do with the original narrative context of the photograph, the intent of its creator, or the way in which it was used by its audience.

Sandweiss (2025) also adds that photographs are static. They stop time dead still and focus our attention on what we can see. They suggest that what we see is somehow more important than what we can’t, that the moment fixed in the photographic image matters more than what happened just before or after.

That private photography has become family photography is in itself an indication of the domestication of everyday life and the expansion of “the family” as the pivot of a century-long shift to a consumer-led, home-based economy. The photographs we keep for ourselves – not always in family albums – are treasured less for their quality than their context. Historically, personal pictures (by the amateur photographer) are deeply unreliable, but it is in the very unreliability that their interest lies.

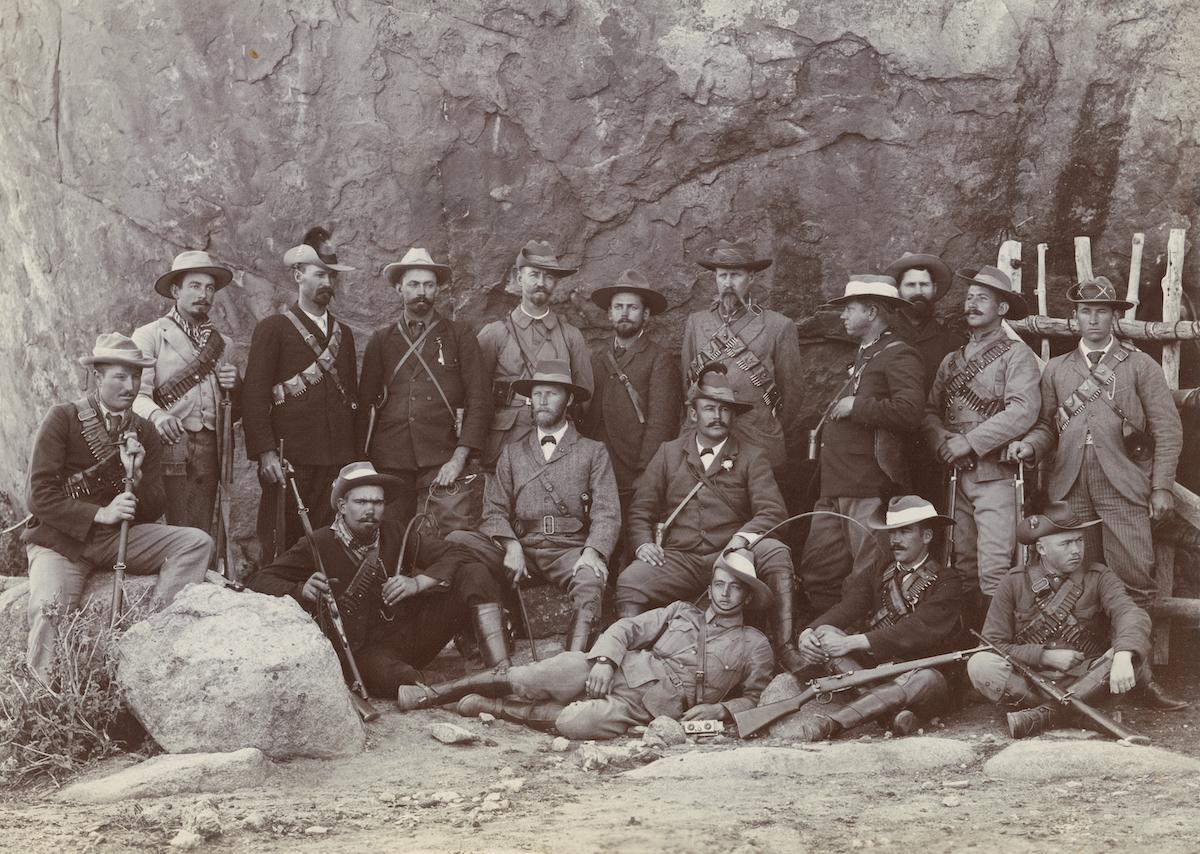

An exceptional photograph of General Jan Smuts (seated in the middle left) with his officers in the Northern Cape shortly before the peace accord in 1902. Although this coloured photograph is Anglo-Boer War related, what makes the image unique is that it includes a rare camera – see image below (coloured photograph provided by Tinus le Roux via Neville Constantine).

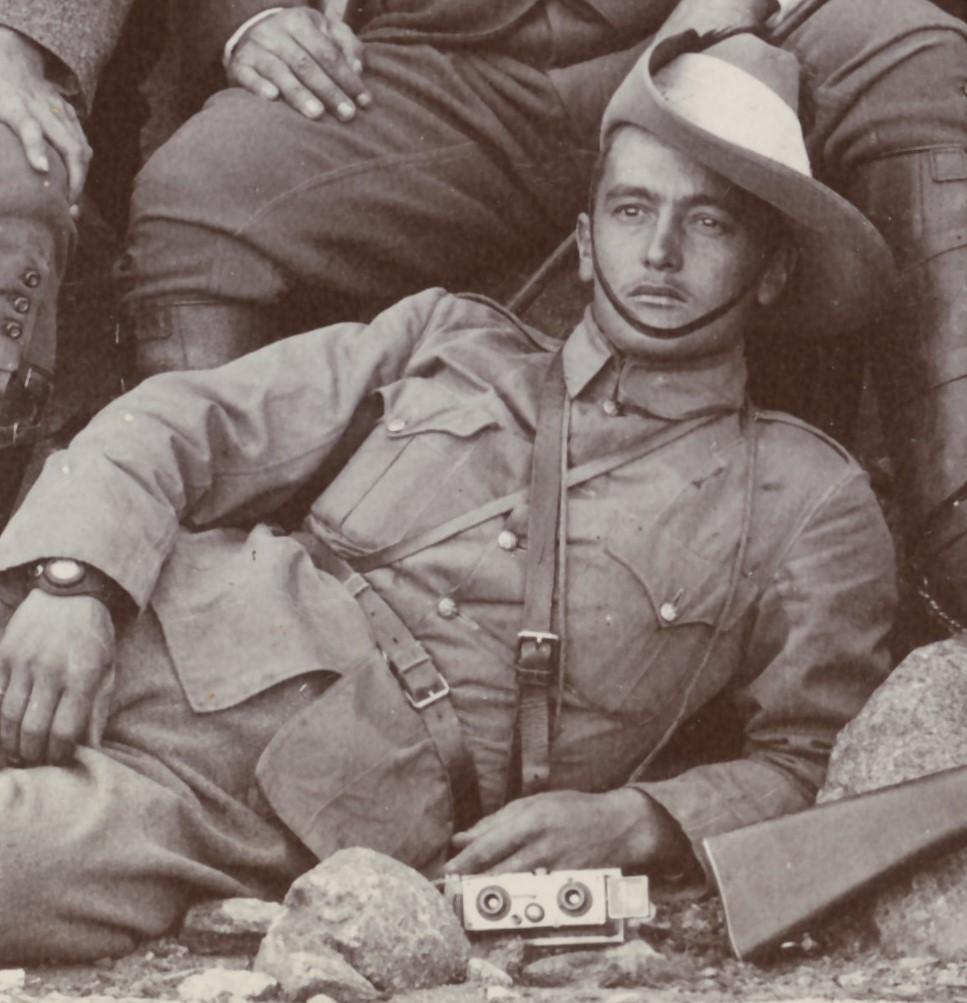

A close-up of the camera on the ground in front of the soldier leaning on his elbow. This camera is a rare French stereo view camera. Tinus le Roux, the Anglo-Boer War colourist, has identified the soldier as the French volunteer Robert de Kersauson de Penneddreff, who also published a book of his experiences in South Africa. None of the stereo views that may have been captured by the Frenchman using this camera have been identified to date (coloured photograph provided by Tinus le Roux via Neville Constantine).

A photograph of a photographer at Spionkop shortly after the conflict between Boer and Brit in January 1900. Interestingly enough, the name of the photographer on the photograph has been erased (bottom right). It is however hypothesized that the photograph is of the Pretoria-based Dutch photographer van Hoepen captured by one of the Kroonstad-based Lund Brothers who have also been recorded to have been present shortly after the conflict.

A close-up of the image above

Closing

The photograph has become a major source of information, but (Wells, 1998) interestingly adds that historians have, for the most part, had an uneasy relationship with the medium, as their professional training did not introduce them to an analysis of visual images. Linked to this argument, in my view, with the omnipresence of social media images, we have unlearned to see. Images are no longer seen for the actual visual message being presented. We have lost our visual curiosity in that we are bombarded with visual imagery daily.

Today, we do not read photographs; we consume them. Sontag aptly warned that photography can make us passive observers, rather than active participants in life. Instead of living, we sometimes aim only to capture.

In the context of travel, it is common to observe tourists briefly disembark from their mode of transport to take photographs before moving on, engaging minimally with their surroundings. For these individuals, the experience is deferred – consumed later through images rather than lived in the moment. This practice, often reduced to aim-and-press photography, raises the question whether such image making still constitutes meaningful photographic engagement. I do not think so.

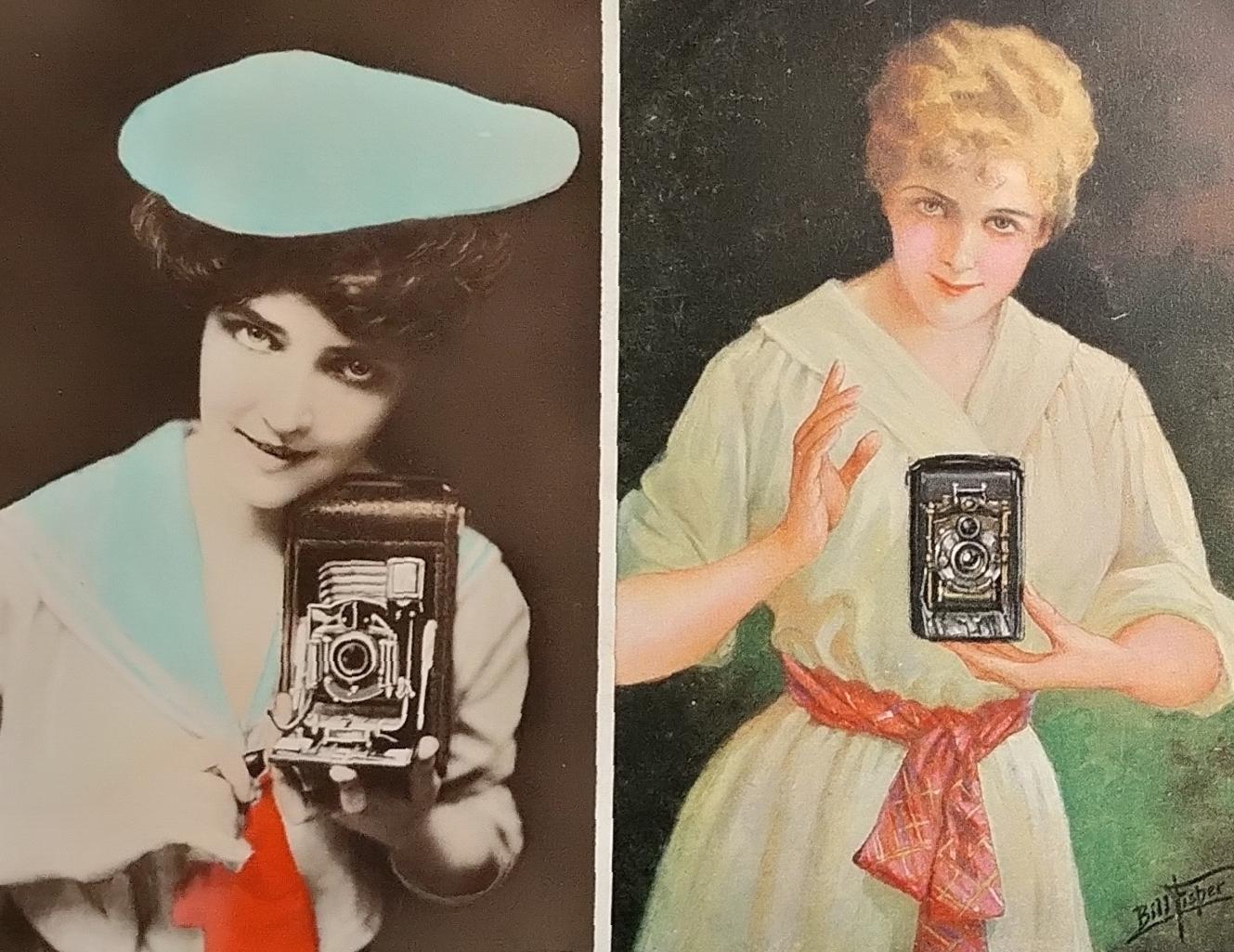

Postcard publishers around the world produced postcards reflecting on the use of cameras. These images, whether actual photographic or art, were either playful (like the images above), humorous or formal with an advertising angle

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Barthes, R. (2000). Camera Lucida. Vintage. London

- Dyer, G. (2007). The Ongoing moment. Vintage books. New York

- Google AI – Carl Jung (extracted 16 December 2025)

- Photography Annual (1963). A selection of the world’s finest photographs compiled by the editors of Popular Photography. Ziff-Davis. New York

- Sandweiss, M.A. (2025). The girl in the middle – a recovered history of the American West. Princeton University Press. New Jersey

- Sontag, S. (1979 & 2002). On photography. Penguin Classics. Penguin Books Ltd. London

- The Deutsche Nationalbibliotek (2014). Just Ask! From Africa to Zeitgeist. Kerber. Germany

- Thurmes, K. (nd). The stories we tell. (www.artifactuprising.com/the-stories-we-tell)

- Traub, C.H; Heller, S. & Bell A.B. (2006). The Education of a Photographer. Allworth Press. New York

- Wells, L. (1998). Photography: A critical introduction. Routledge. New York

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.