Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Photography is the only “language” that is understood worldwide, resulting in a bridge being created between nations and cultures – it connects the family of humanity. Independent of political influence – where people are free – it provides us with an honest reflection about life and events, allows us to share in the hope, joy and despair of others, and potentially lightens political and social burdens. This way we become witnesses, not only of humanity, but also of the brutality of human kind (Gernsheim as quoted in Sontag 1977).

Since the first war was photographed during 1846, photography and war have become inseparable. Any war photographed fills gaps in our perception around the events and occurrences surrounding it. It provides for an improved context.

South African photographs from the Anglo-Boer War, those that have survived, have become additions to our heritage.

Image of Boer Prisoners of War held at Diyatalawa Camp in Ceylon. What makes this image unusual is that the name of each of the 54 individuals on the image has been captured on the back of the photograph. Photograph was initially thought to have been taken at the Ragama camp. Originating format – unknown.

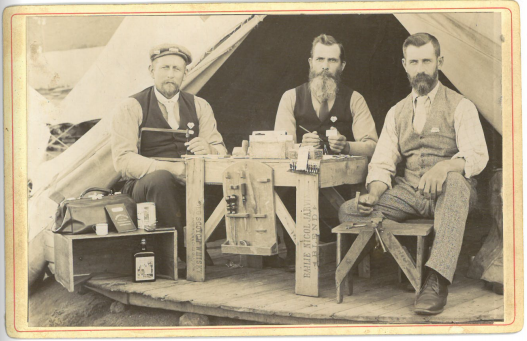

Unknown concentration camp. Carpenters. The table is clearly made out of whiskey crates (Format – Cabinet Card)

Images from the Anglo-Boer War today provide the viewer with a visual impression of a past that seems unreal but has clearly been described by the various narratives around the war.

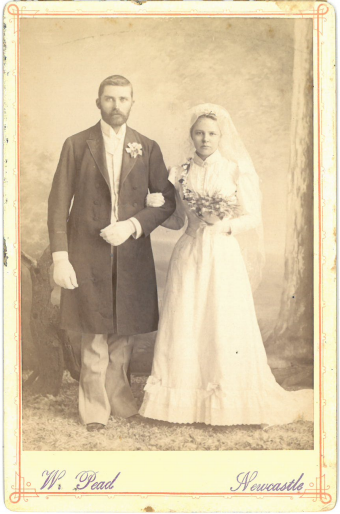

Not only are the photographs of the actual conflict of importance, but also the social structures at the time. Family photographs taken during the war provide additional contextual perspective around social structures (both formal and informal), relationships as well as the pain and suffering associated with the war.

Although not the first military campaign to be photographed, the Anglo-Boer War coincided with many of the technical advances on which modern photography is based today. Modern film, produced mainly by Kodak, only just came into use during the Anglo-Boer War whereas glass plates would still have been used in the preceding wars resulting in the better quality images.

Professional photographers have been active in most hostilities since daguerreotypes were taken of the Mexican War (1846-1847). The daguerreotype was the first photographic format, an invention by the Frenchman Daguerre (1839).

Photographs from the Crimean War (1854-1856) are however acknowledged as the first serious photographic records of a military campaign.

During the Anglo-Boer War, no professional produced any work to compare with the pictures of the earlier wars such as the Crimean or the American Civil War (1861-1865). Photographs produced during these wars were simply of better creative and visual quality compared to those produced during the Anglo-Boer War. Even though the Anglo-Boer War took place some 35 years after these wars, this failure was one of style by photographers during the War, rather than a lack of suitable equipment.

At the time of the War, cameras were in general use, and were carried by officers, troops and newsmen. As a result, there are many thousands of photographs in museum archives, private collections, auction sites or potentially still undiscovered.

What makes the field of Anglo-Boer War photographic research and collecting interesting is that photo-realism lay far in the future. The majority of photographs were posed for, while captions were frequently misleading.

The Sitters are Hauptfleisch, Kruger, Ferreira & Beck (all four teachers). Format – Cabinet Card.

Dead wood Camp music group – St Helena 1902. Name of each band member included (Photographer unknown)

Emmanuel Lee, in his book To the Bitter End confirms this sentiment: “War images seem embalmed in nineteenth-century heroic rhetoric”.

In With the flag to Pretoria, the following interesting reference is made to Anglo-Boer War photographs:

A word of reproach is due for the ghoulish and horrible photographs of the field of battle which the Boer generals allowed to be taken, and which the Boer government permitted to be paraded in the shops of Pretoria and Johannesburg.

This statement was more than likely a reference to the dramatic and factual war scene photographs taken by Pretoria based photographer, van Hoepen. It has been suggested that van Hoepen, Dutch by origin, was one of only a handful of photographers that took photographs of the actual gory consequences of the war.

A variety of emotional allegations between the warring parties have also been made. It has been suggested that some photographic images portrayed lies. One such example is mentioned in After Pretoria:

“(South African) children had been photographed by British authorities to bring home charges of neglect and cruelty against their Boer mothers!”.

Photographic images of prisoner of war scenes, images of groups, black South African’s participating in the war, war personalities or images showing aspects such as communication equipment, weapons, uniforms etc. remain of particular interest to collectors and researchers.

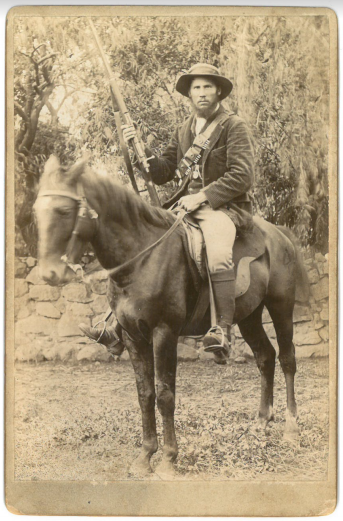

Print from a glass negative showing unknown black male – clearly an active participant during the Boer War. This image was found amongst a donated batch of other “insignificant” glass slides. The author assumes that this image might have been taken in Graaff Reinet. Photographs of black soldiers, whether they fought on the Boer or the British sides, are scarce. Originating format – from a glass negative.

Photographs produced during the Anglo-Boer War appear in different photographic formats, namely:

Stereo Photographs (stereo cards)

One of the photographic excitements at the time of the war was that of the stereoscopic photograph, which resulted in a three-dimensional effect when viewed through a stereo viewer. The publishers of the better-known stereo cards were those by Underwood & Underwood, two American brothers, who sold sets of these images to the public. More titles were added as the war went on.

Other publishers of stereo cards, often of better quality compared to those produced by Underwood, included Keystone, Kilburn, American Stereographic Company and Australasian Stereographic Company.

It has been suggested that more than 3000 of these views were published by all the publishers combined.

Some publishers numbered their cards, whilst others did not. The author has started an alphabetic, and where appropriate, numeric catalogue in an attempt to identify as many of these cards as possible. This in itself is a life task in that only some 1050 numbers and titles have been recorded to date.

Cabinet card format photographs

What makes Cabinet Cards unique is that, unlike the stereo cards, they were not commercially produced. Each photograph is relatively unique in that it was mainly produced in a studio as a full length or bust portrait. Outdoors photographs in this format can also be found of people and scenes. These are however less common.

Photograph by McKenzie and Brown – Unknown town. Nurse not named (Format – Cabinet Card)

The original image was mainly produced on glass where after the final paper based image was mounted on a stiff piece of cardstock. The size of the Cabinet Card is roughly 15.9cm x 10.8cm.

What makes this format interesting is that often the photographer’s name is either printed or embossed on the front or the back of the photograph.

Cabinet Card by Victoria West based photographer GH Church of Penkop (young male) Ralph Kruger. During the war many boys also participated in the war.

Cabinet photographs of most interest to the author in terms of his research, are those taken locally by South African based photographers.

Due to the age of these images, they have become difficult to obtain. Some photographs can still be found in family photo collections, often discarded or thrown away when passed on from one generation to the next. Considering that the war took place some 115 years ago, people in the majority of instances sadly do not associate these studio images with the Anglo-Boer War any longer.

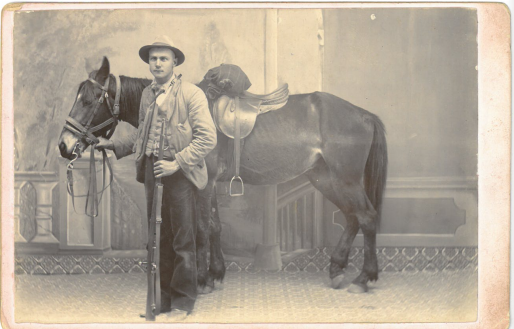

Boer soldier F.P. du Plessis and horse in unknown studio. Format – Cabinet Card.

Although British soldiers also visited local photographic studios during the Anglo-Boer War, they often had studio photographs taken of themselves at their home village/town prior to them departing for South Africa or on their return from South Africa.

British soldiers also had more of an inclination to photograph themselves compared to the Boer soldiers resulting in images of Boer soldiers being scarcer.

Sadly, in terms of these photographs, very few of the names of the sitters have been recorded on the photograph. Less than 10% of these images will have the name of the sitter captured.

The majority of the images included in this article are of Cabinet Card format.

Boer soldier Gysbert Keet. Photograph by Daubert – Wakkerstroom. Format – Cabinet Card.

Standard paper print (from roll films)

The first hand held roll film cameras were already available during 1888 – produced by Kodak, meaning that during the Anglo-Boer War these cameras would have been in general reach of the South African public, photojournalists and soldiers.

It is recorded that Malcolm Riall, a British soldier from Aldershot in England, owned a Kodak Camera. With this camera he kept a visual record of his experience in Africa. He would return each film to Aldershot to be developed. His family, based in Ireland at that time, would then get to see the photographs first, before they returned them to Malcolm in South Africa (Riall, 2000). This means that Malcolm would only have seen photographs taken by himself probably more than 3 months later.

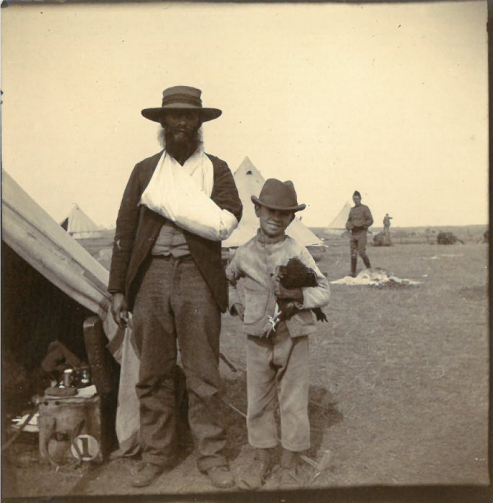

Father and son at unknown concentration camp. Note the British soldier in the background and the pet chicken been held by the boy. Originating format – Roll film print.

Postcards

The first full photo postcards were issued in England during November 1899. Postcards produced during the Anglo-Boer War are known to be the first mass produced postcards. These postcards, many with actual images, today have become historical documents in their own right.

They also contributed to an expanded communication between soldiers and their families back home. This resulted in an improved awareness amongst recipients of these cards. Collectively, these cards provide a credible narrative of the war. It was these stories and images that people shared with each other.

Magic lantern slides

Both photographs and etchings about the war were placed between two thick glass sheets and then projected to audiences during magic lantern shows, mainly in Europe.

Even some 115 years after the event, we still remain intrigued by the war, resulting in research still being conducted and books being published on the topic. Two such examples are:

- PhD research being conducted by Fred du Toit. The title of his research is: Interpreting images from South African family photographic collections of the Anglo-Boer War period 1899 to 1902.

- New book by Friedel Hansen. Titled: Die Oorlog (1899 -1902) - ‘n Fotoalbum with an anticipated release before end of July 2017. This book includes multiple images never published before.

All the images included in this article form part of the Hardijzer photographic research collection.

Boer War related photograph - Lettie Eksteen & Andries de Jager on their wedding day 10 January 1895. Inscription in album reads: “(During the Boer War) they skinned Andries alive – He died three days later”. Format – Cabinet Card.

Main image caption: Cape Stormberg rebel (tall man between three British soldiers) during a military hearing in Colesberg. This man was allegedly sentenced to death (Originating format – unknown)

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources:

- Du Toit, F. (PhD article - n.d.). Interpreting images from South African family photographic collections of the Anglo-Boer War period 1899 to 1902. Tshwane University of Technology.

- Hardijzer, C.H. (11 November 2006). Anglo-Boereoorlog vasgevang in Beeld. Adaptation of article as it appeared in Beeld newspaper.

- Haythornthwaite, P.J. (1987). The Anglo-Boer War. Arms & Armour press. Great Britain.

- McDonald, I. (1990). The Anglo-Boer War in Postcards. Bok Books. Durban.

- Lee, E. (1985). To the bitter end: A photographic history of the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902. Penguin Books. England.

- Riall, N. (2000). Anglo-Boer War – The letters, diaries and photographs of Malcolm Riall from the war in South Africa 1899-1902. Brassey’s. London.

- Sontag, S. (1977). On Photography. Penguin Books. London.

- Wilson, H.W. (1900). With the flag to Pretoria – A History of the Boer War. Harmsworth brothers. London.

- Wilson, H.W. (n.d). After Pretoria – the guerrilla war. Harmsworth brothers. London.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.