Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Following the announcement that a Johannesburg-based book dealer was relocating from Johannesburg to Cape Town and that he was offering material at discounted prices, I went scratching.

Amongst others, what did I find? A photo album containing 31 large format photographs, 26 of which are of particular interest to me. Amongst these 26 images are 15 photographs by the photographer, Henri Ferdinand Gros. This alone sealed the deal – the album was bought purely because of the HF Gros images.

Gros, a Swiss citizen, who was active in South Africa between 1869 and around 1895, is recorded as having been Pretoria’s first permanent photographer. He was also the first to record early Transvaal photographically, which makes his work unique.

Although the album contained these 15 valuable Gros images of early Transvaal, this is not where the story is going.

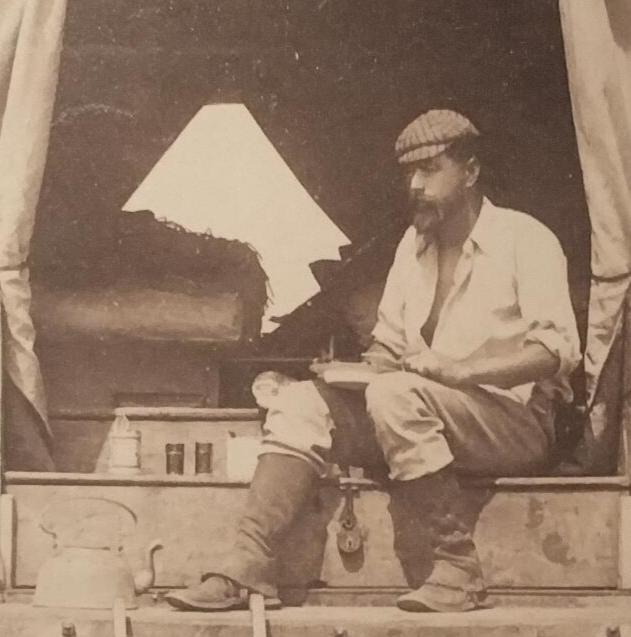

The album contained some additional provenance - it belonged to P. Baily Eastwood. One of the photo inscriptions underneath a photograph of Eastwood states that he was a photographer, baker and cook, presumably whilst travelling the Transvaal around the 1890s. This provenance diverted my attention from the Gros photographs.

Philip Baily Eastwood (circa 1890). The photograph is inscribed "P. Baily Eastwood - photographer, baker, cook, etc. - Our house and home July and August 1890." The man standing on the right is in all probability his assistant Piet.

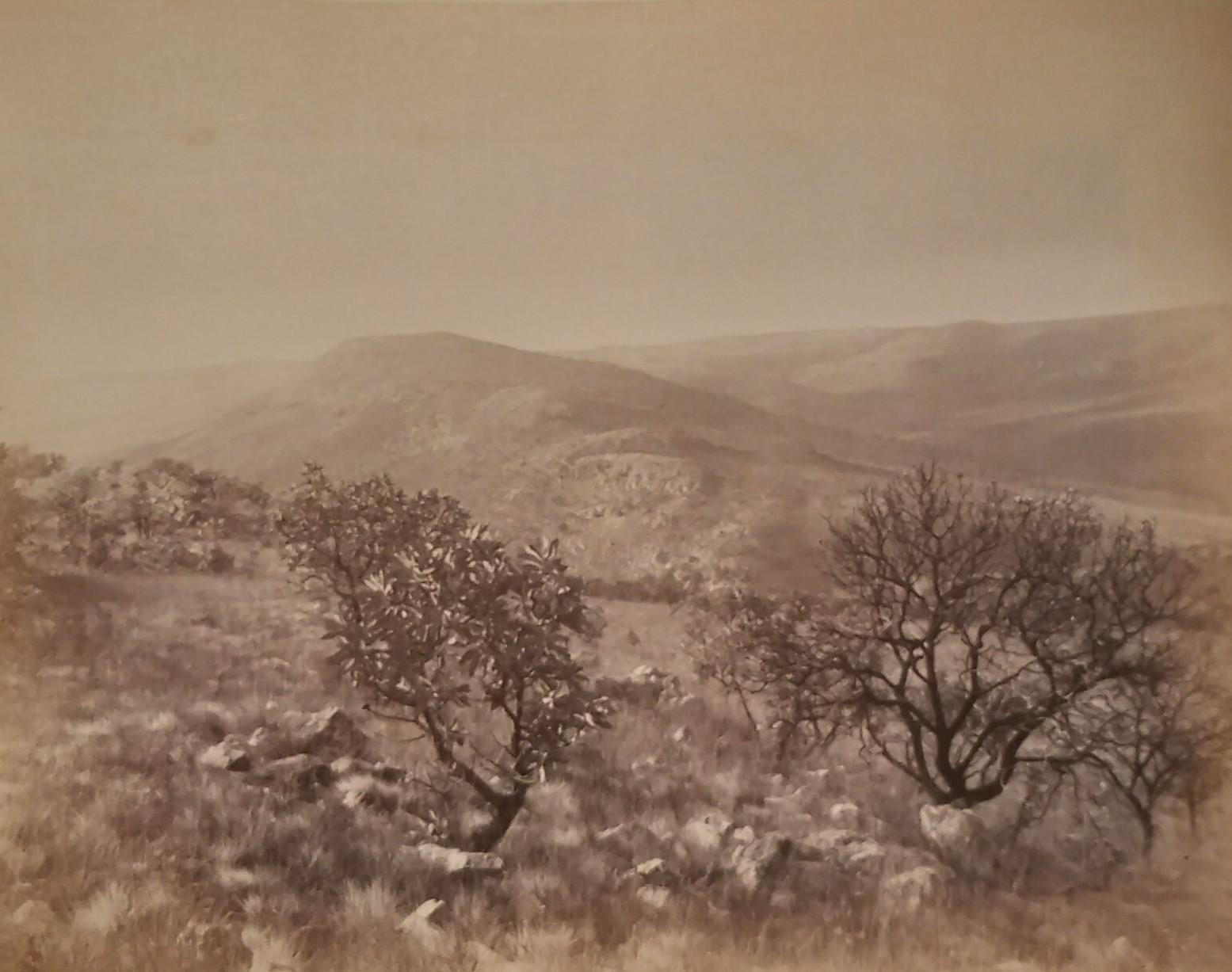

From the Eastwood album - Photograph by HF Gros - circa 1888 (# 556 - Haenertsburg in Zoutpansberg District). Eastwood would have bought a print of this photograph some 2 years after it was captured by Gros. Eastwood was clearly travelling the Zoutpansberg area in the early 1890s before settling in the Waterberg area for a few years.

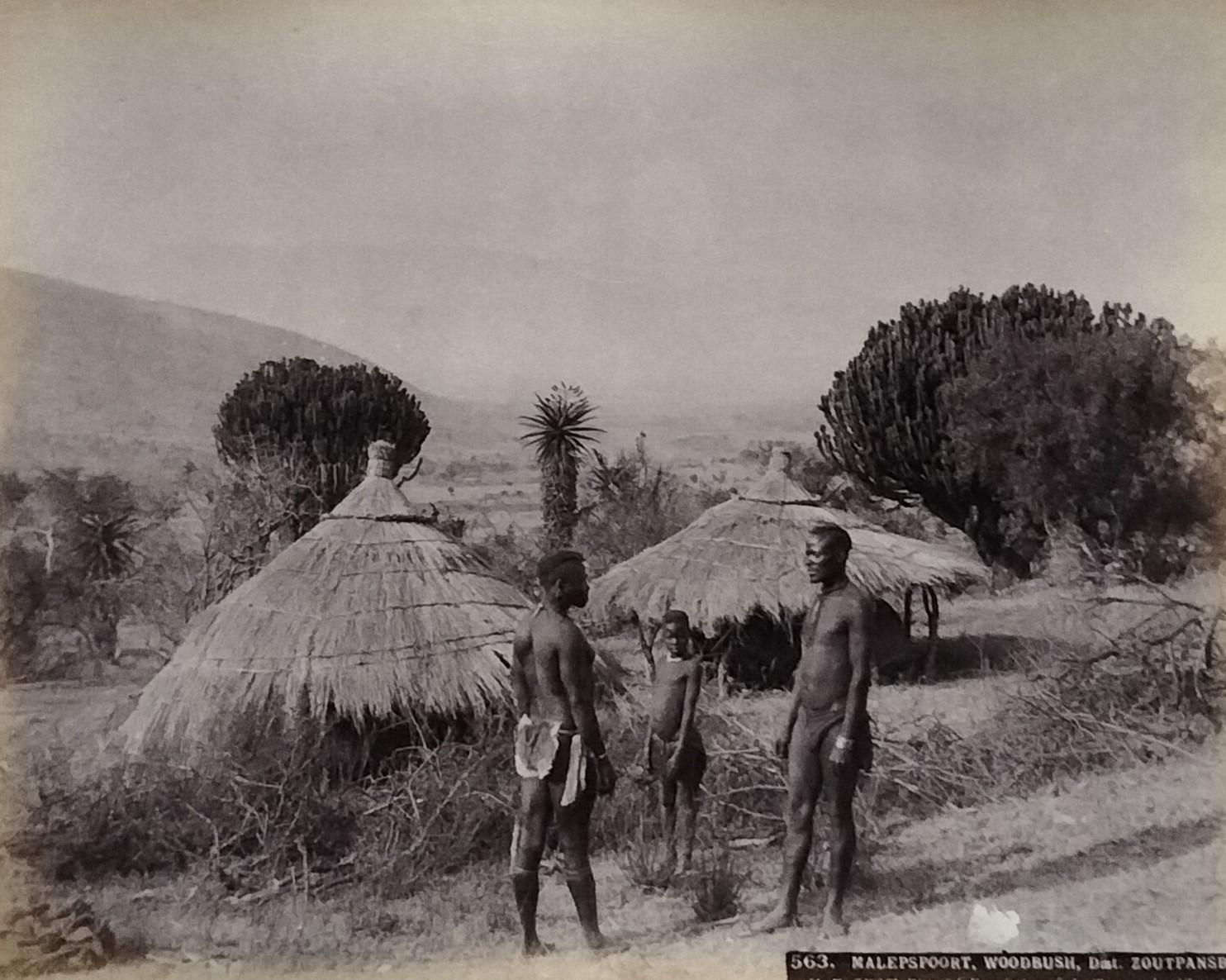

From the Eastwood album - Photograph by HF Gros - circa 1888 (#563 - Malepspoort - Zoutpansberg District). Eastwood would have come across ethnic groupings in their natural environment during his travels, therefore his interest in acquiring such photograph.

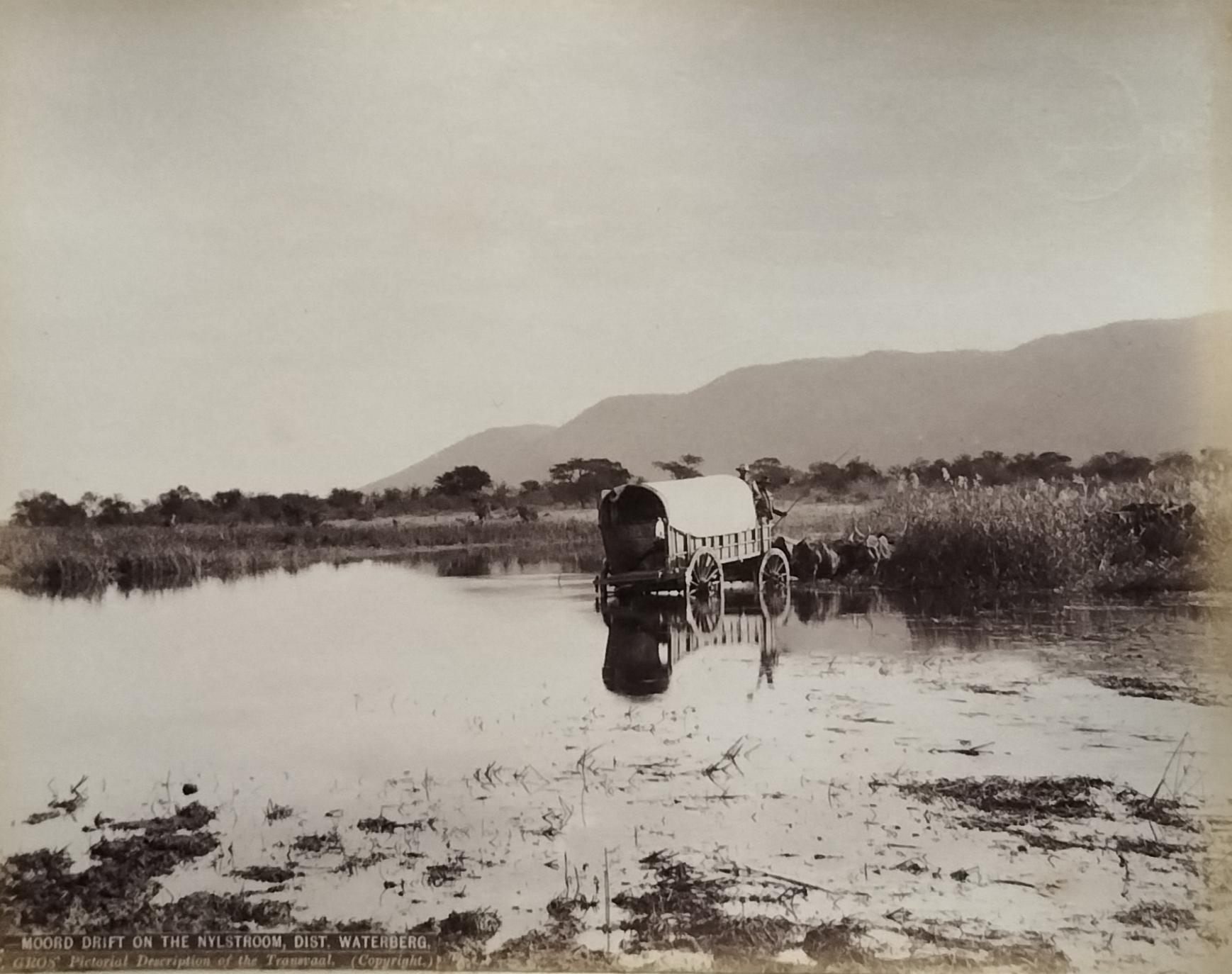

From the Eastwood album - Photograph by HF Gros - circa 1888 (#506 - Moord drift - Nylstroom). Eastwood used a similar ox-wagon during his travels in the Zoutpansberg/Waterberg districts.

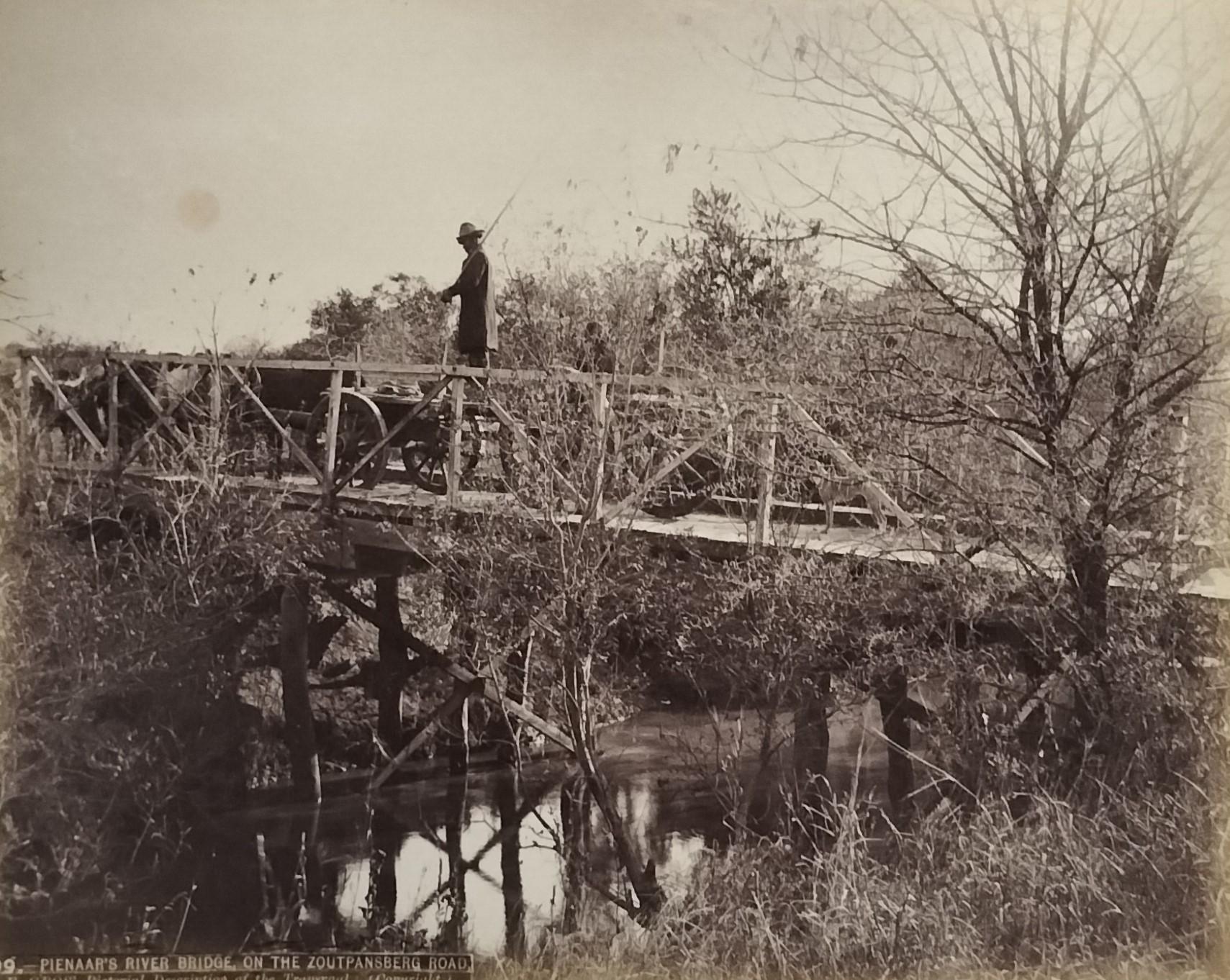

From the Eastwood album - Photograph by HF Gros - circa 1888 (#499 - Pienaars River Bridge on the Zoutpansberg Road). Eastwood would have traversed this bridge on a number of occasions during his travels. Note the bridge's wooden structure.

From the Eastwood album - Photograph by HF Gros - circa 1888 (#389 - Stuck in the mud in Six-Mile-Spruit near Pretoria). Eastwood would have experienced similar challenges during his travels with his ox-wagon through the Zoutpansberg/Waterberg districts.

From the Eastwood album - Photograph by HF Gros - circa 1888 (#430 - Witwatersrand). Eastwood is described as a Rand pioneer where he also became one of the first Rand Club members.

The primary theme of the album relates to Eastwood’s travels to South Africa and subsequent journeys overland. It starts with photographs of Madera, Cape Town and Pretoria followed by mainly the Waterberg and Zoutpansberg, the area where he resided between mid-1890s and early 1900s. Eastwood would have bought the Gros photographs contained in the album directly from Gros or a stationery dealer.

On researching Eastwood, I stumbled upon Philip Baily Eastwood on an Anglo-Boer War medal website which contains a well-researched and constructed article on him.

Although the one inscription in the album suggests that Eastwood was a photographer, the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection has not previously identified Eastwood as a professional photographer. It may therefore be that he was an amateur photographer. Some photographs included in the photo album are thought to have been captured by him. These images suggest that he was competent in the art of photography and not simply a “happy snapper.”

Much of the content below has been replicated from the AngloBoerWar.com site from the article by Rory (surname unknown) titled: Philp (sic) Baily Eastwood – A Rand Pioneer and Soldier. For a detailed read, with photographs of medals awarded to Eastwood click here.

The Life of Philip Baily Eastwood

Philip Eastwood was one of those larger-than-life characters. He came to South Africa in search of adventure which he found in abundance.

Born in Bradford, Yorkshire on 15 August 1861 he was the son of a businessperson and banker, William and Emily Anne Eastwood.

Having finished his schooling, Eastwood set his sights on making his way in a country far from his home following which he settled in South Africa. When he arrived in South Africa is not known, but he would have been in his late teens.

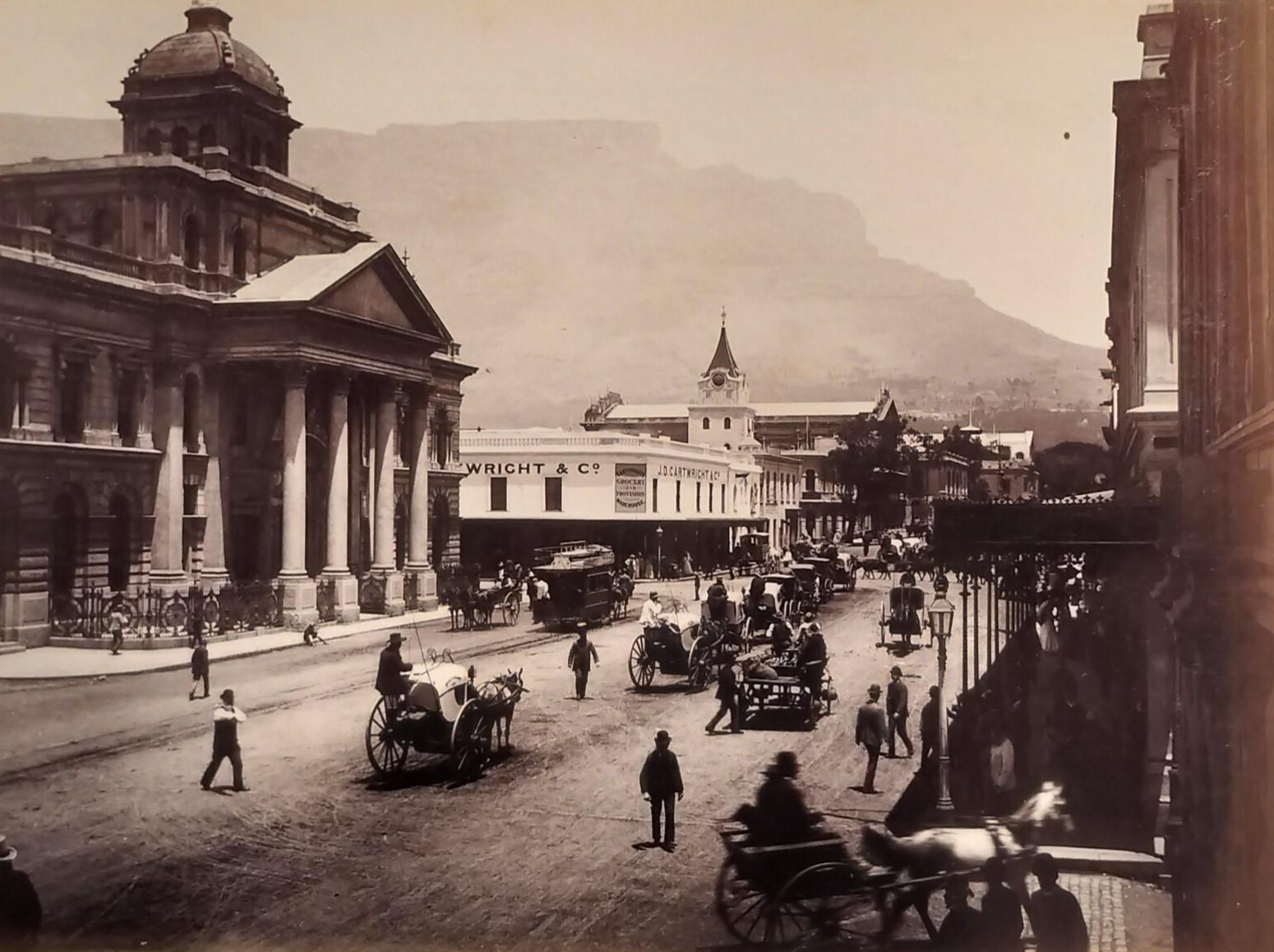

Early Cape Town and Table Bay (circa 1880s). This photograph is thought to have been captured by Eastwood shortly after his arrival in Cape Town.

Adderley Street, Cape Town circa 1880s. This photograph is thought to have been captured by Eastwood shortly after his arrival in the city.

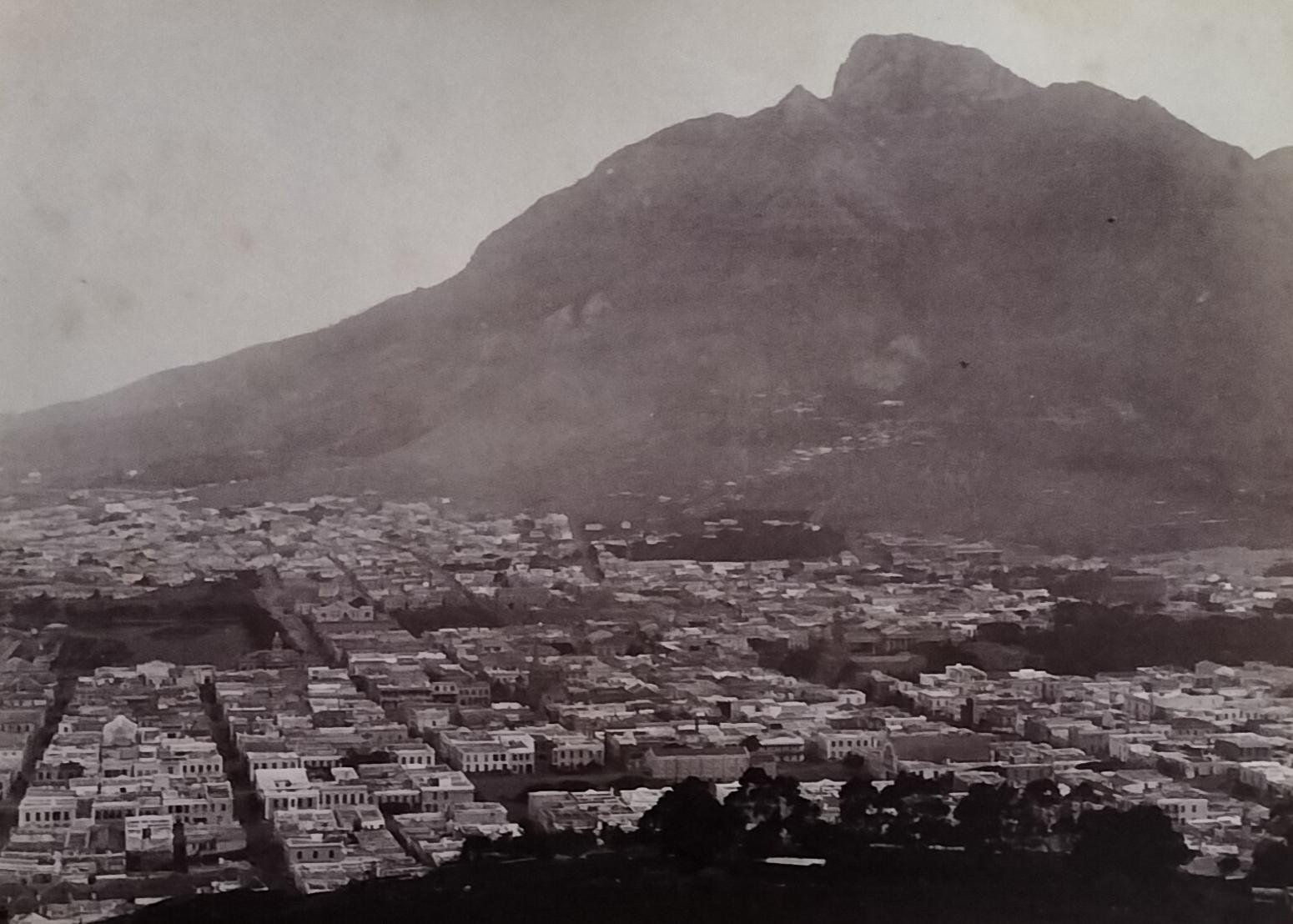

Cape Town and Table Mountain circa 1880s. This photograph is thought to have been captured by Eastwood shortly after his arrival.

Initially residing in Cape Town, Eastwood was soon part of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Volunteer Rifles, and it was not long before he was thrust into action in what became known as the Basuto Gun Wars.

Matters came to a head in 1879 when Governor Henry Bartle Frere reserved part of Basutoland for white settlement and demanded that locals surrender their firearms to Cape authorities under the 1879 Peace Protection Act. The Cape government, under Sir John Gordon Sprigg, set April 1880 as the date for surrendering weapons. Although some Basotho, with great reluctance, were willing to surrender their guns, the majority refused resulting in conflict by September 1880.

On 22 September 1880, Eastwood was one of a contingent of 9 Officers and 290 men of the Dukes that were placed on active service. They left Cape Town 3 days later aboard the steamer Melrose destined for East London, whereafter they then began the long march arriving at the Basutoland border on the 16 October 1880.

A peace treaty was eventually signed with the Basotho chiefs in 1881, in which colonial authorities conceded most of the points in dispute. The land remained in the Basotho’s hands and the nation enjoyed unrestricted access to firearms in exchange for a national one-time indemnity of 5,000 cattle. However, unrest continued, and it quickly became clear that the Cape Colony could not control the territory.

For his efforts, Eastwood was awarded the Cape of Good Hope General Service Medal, oddly only authorised by Queen Victoria on 4 December 1900, at which point those still living could apply for their medal. The Basutoland clasp was also awarded to Eastwood for operations from 13 September 1880 to 27 April 1881. Prize money for cattle confiscated from the Basuto was also awarded to the rank and file, with Eastwood getting his fair share, according to the roll in 1883.

At the age of 21 on 9 July 1883, he enlisted with the Cape Mounted Rifles. Physically, he was described as having a dark complexion, brown eyes and brown hair; he was 5 foot 7 inches in height.

Less than two years later, on 23 April 1885, Eastwood purchased his discharge for the sum of £12 and said farewell to a uniform as he clearly had more ambition than to be a trooper. 23 years old at the time, he was described as being of good education, sobriety, zeal and efficiency.

Having made his plans, he set off for the hustle and bustle of Johannesburg (or the Witwatersrand Goldfields as it was then called). Booming Johannesburg offered the young and highly spirited every opportunity for advancement.

Eastwood’s obituary, which came many years later, mentioned that “He was riding across what is now the Rand when he saw a few tents and was told of the gold discovery, and he remained.” In the process, he became a Rand Pioneer.

Eastwood’s brother joined him in Johannesburg in 1887 and relates the following story:

My brother Phil met me between Potchefstroom and Johannesburg, at a small wayside outspan, with an American spider and two ponies. He packed the cart and designedly put my bowler hat on the top. I had unearthed a soft felt hat by that time. We jogged along and the first suitable rut in the road saw my bowler hat under one of the wheels and all he said was, "Good shot!”

He was then prospecting for gold on a farm called Witpoortjie, some ten miles west of Johannesburg, with a partner called le Roux. This was our destination, and we spent a couple of weeks there, panning for gold and living on mealie-pap with treacle and fresh milk, which I thought was splendid. We occasionally had eggs and occasionally went without.

For a special event, Phil one day took a large square basket on horseback to fetch eggs and bread from a neighbouring farm. He carefully put the loaves at the bottom of the basket and the eggs on top and, on nearing the house, something startled the horse, it bolted and, as it passed the door, I noticed him holding the basket well out at arm's length to prevent jolting and the horse making for its shed, inside a stone kraal. He jumped the wall, the bread rose, (I doubt whether it had ever risen before) the eggs rolled under the bread, there was a splash, and a yellow veil enveloped poor old Phil. He came in to change; I did not ask any questions, but I noticed there was only mealie-pap for supper that evening.

Prospecting for gold is really exciting. You have your gang of boys opening up surface indications on what is known as the ‘banket' or conglomerate formation, then as you get down on the reef you take samples and, after reducing them to a fine powder with pestle and mortar, you put the residue in a circular basin or pan and commence to wash it, the heavy metal gradually finding its way to the bottom. As you proceed you push off the top surface and at the end of the process you find, (sometimes) a light streak of pure gold and your spirits rise or fall, in proportion to the length of the streak. You hear of ‘finds’ on adjoining farms in similar formations and interest never flags.

Eastwood and his partner were having no luck on the Witpoortjie farm where they were prospecting and returned to Johannesburg. Eastwood, along with his brother and Captain Maynard, shared a thatched building of three rooms in Ferreira’s Township, just outside the then centre of Johannesburg. The three, firm friends, joined The Rand Club, of which Maynard was Chairperson, by so doing becoming three of the original two-hundred members, who formed the first syndicate.

Whilst based in Johannesburg they also founded the firm of Eastwood Brothers and Le Roux. A signboard was placed outside their offices advertising themselves as ‘Company Promoters, Financial Agents, Accountants, Secretaries of Companies and Insurance Brokers.’ This enterprise didn’t appear to last for any length of time with Eastwood moving to Potchefstroom where he went into partnership with an Irishman called Peard. They had floated a syndicate and were making money. According to Eastwood’s brother:

They had a very nice house and were living in the lap of luxury. They paid a coloured woman £10 a month to do the cooking and housekeeping. She was a noted cook and a more noted thief. Well, I settled down and soon began to notice things. The first Sunday they had hot sirloin of beef for dinner at midday, a joint certainly weighing 9 lbs. Naturally, I expected to see it cold for supper, but was surprised to see a cold leg of mutton. On the Monday for lunch, they had steak, so I said to Phil, “What about the sirloin and mutton?” He replied, "Oh, we never see a joint twice and I really never gave it a thought.” It appeared that every evening when the cook returned to the location, she was accompanied by half a dozen members of the family, who took the surplus with them.

Eastwood also became somewhat of a prize pugilist or “champion fighter” whose prowess was about to be put to the test. Potchefstroom was a delightful place with the Kimberley coach to the Rand that passed through the town. The Post Office became a rendezvous for people collecting their mail and seeing the new arrivals. The coach was driven by a coloured man, a ‘bruiser’ from Cape Town, who was the terror in town and used to insult everyone, white and black. Eastwood who, when with the Cape Mounted Rifles, had fought in the ring and knew that eventually he would have to take the Cape Townian on. He was not keen on the job but just kept himself fit and awaited events. The ‘bruiser’ applying free license as he went around, became worse and worse resulting in him being a great topic of conversation amongst the white inhabitants.

Eastwood had a driver called Tati, who simply worshipped him. He was someone you could trust with anything. At times when money up to £150 had to be left in the house for paying licenses on claims or options on the farm, Eastwood had hidden such sums between his mattresses and had told Tati to look after it. He had never failed. Eastwood’s brother took up the story:

Well, one day we found the boy in great distress, for the ‘bruiser’ had told him that if his ‘boss’ did not look out, he would put him across his knee and spank him. To hear such an insult to his ‘boss’ had simply stricken Tati. Phil saw trouble ahead and made preparation to square matters with the cause of it, so one evening we went down to the hotel stables, where the coach was outspanned, and Phil went up to the ‘bruiser’ and said he understood he wished to speak to him. Without any hesitation, they both stripped, a crowd collected, and they were at it.

When in the C.M.R. Phil had seen a great fight, between a ‘non-com’ in the Seaforth Highlanders and a Malay man. The soldier had lost the fight because he had gone for the Malay's face and smashed up his hands. For the first two rounds of the fight I am describing, Phil was inclined to follow the Highlander’s tactics but found he could make no impression on the Cape boy, who was holding his own. Time was called and they went to their corners. Then Phil decided to alter his mode of attack.

The third round started furiously. My brother was perfectly cool to outward appearances but no doubt boiling inside. In the middle of the round Phil caught the boy in the wind with his left, the boy’s head came forward and, with a terrific uppercut with his right under the chin, the boy dropped like a stone. He lay on the ground half insensible, and the fight was over. News of the event spread through the town and Phil had made a name for himself, which never left him. Couper, the English middleweight, told me he had never met a man of Phil’s weight with such a wonderfully cool head for fighting and one who could hit so hard. The only damage Phil suffered was that one knuckle of his right hand was forced back quite half an inch with the force of the final blow and remained so. Phil was a most even-tempered man when trouble was about but never avoided it when it was forced upon him.

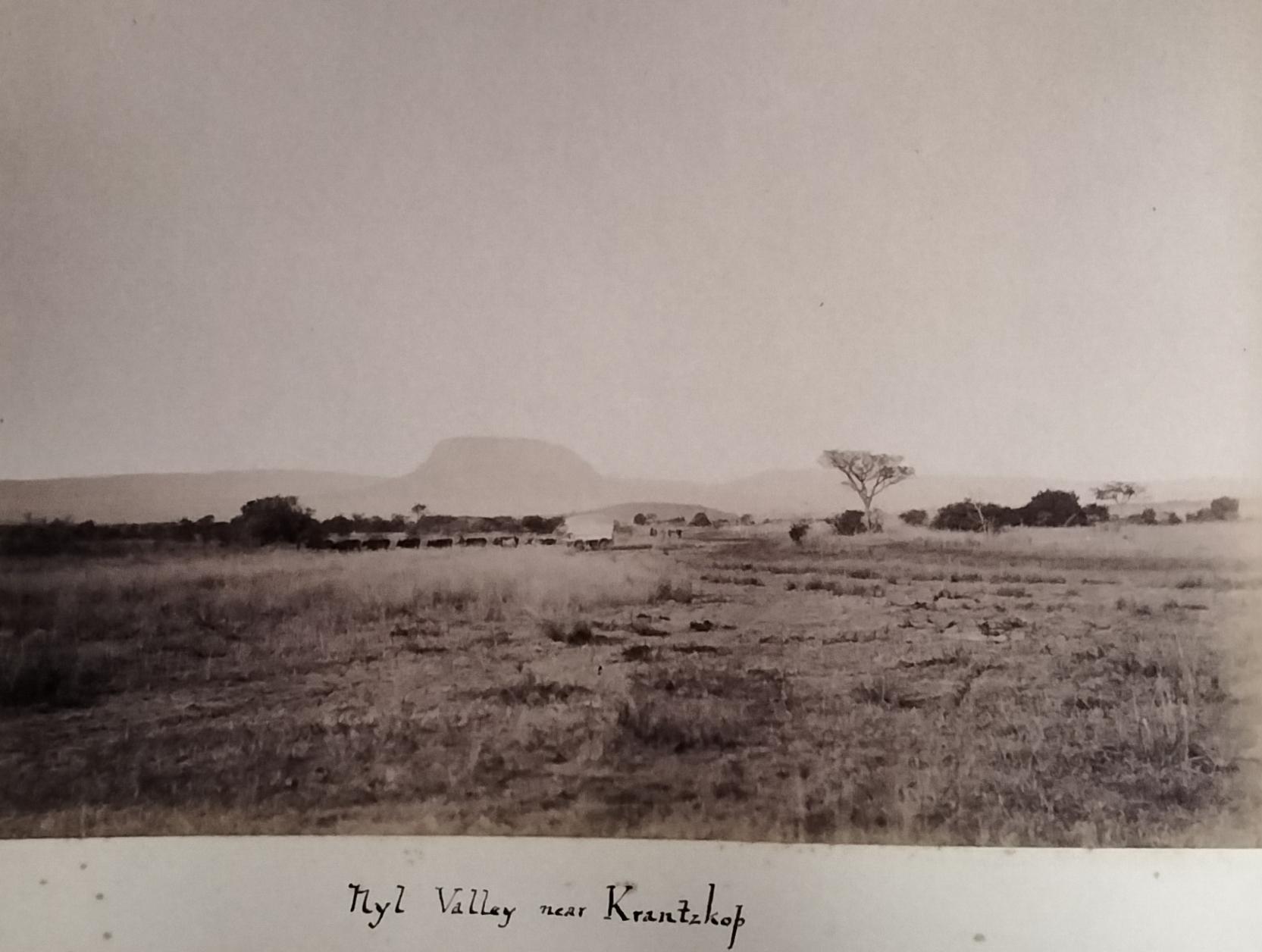

After several failed business ventures, Eastwood was appointed as the assistant manager of a land company in the Northern Transvaal in 1896, later being appointed as the manager. He also purchased a Bushveldt farm in the Waterberg near Nylstroom. The homestead was described as a perfectly sheltered spot, with a thatched cottage, a small orchard, and a garden from the stoep (veranda) which overlooked a patch of tobacco, which Eastwood had succeeded in growing after re-planting five times. Beyond it was a very useful dam.

Nyl Valley near Krantzkop (circa 1890s). This photograph was captured by Eastwood and shows his wagon in the distance.

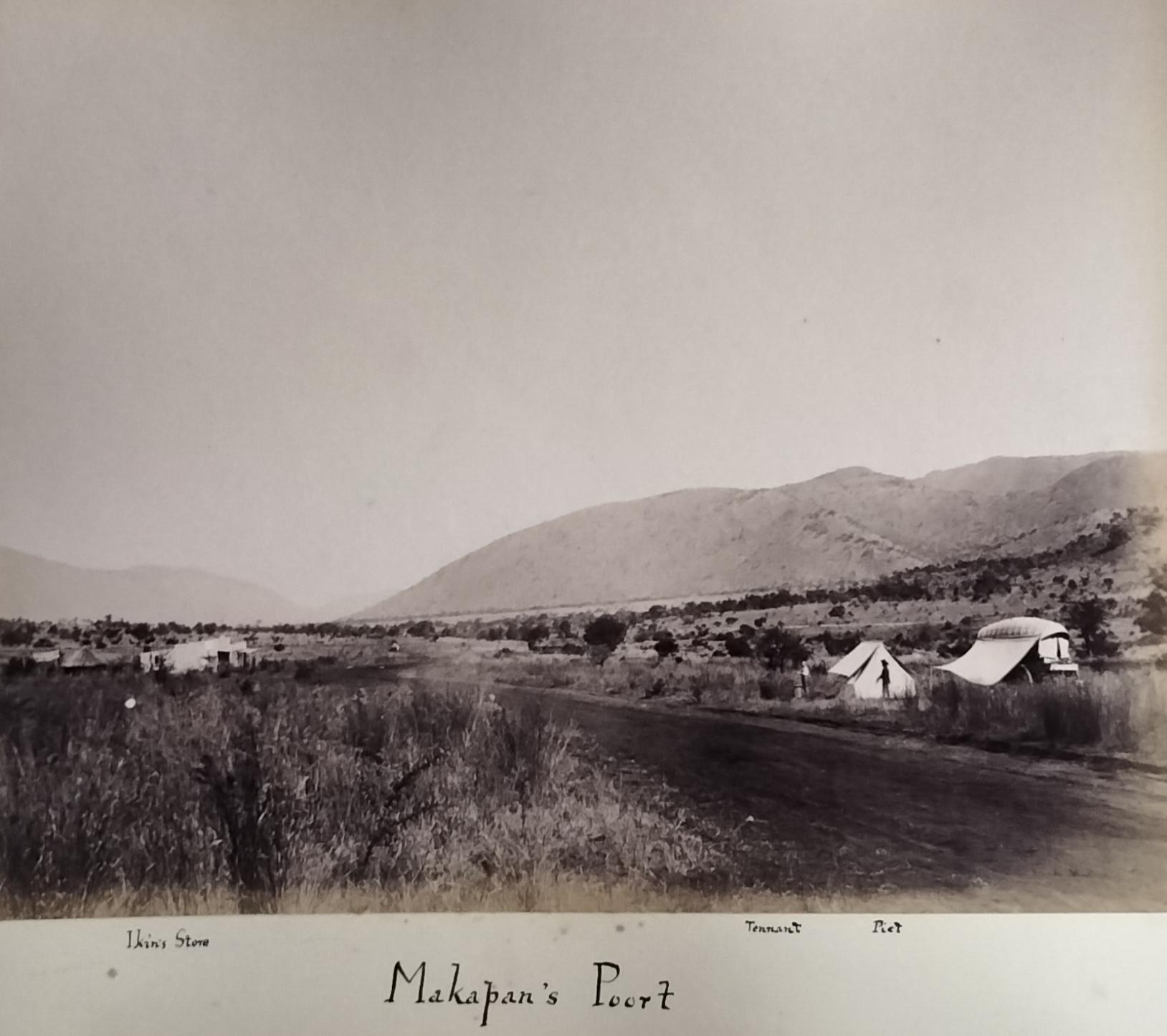

Makapan's Poort (circa 1890s). This photograph was captured by Eastwood and shows Ikin's store on the left. The two figures standing at the tent next to the wagon have been recorded as "Tenant" and Piet. Piet was probably Eastwood's employee during his ox-wagon trip through the Zoutpansberg/Waterberg district.

The outlook from the stoep (veranda) was simply grand overlooking bush country, with that lovely effect of light and shade on the mountains beyond. His brother wrote that:

In those mountains were situated two of the most beautiful farms in the Waterberg and Phil always used to say that if he could acquire them, he would want nothing else on earth. He bought them later on and entered into a labour contract with the Chief Zebedela whose territory adjoined, by which the latter was to supply so many hundred boys per annum, who would be sent down in squads to the mines, in exchange for which Zebedela was to be allowed to cultivate on Phil's farm, some thousands of acres, for his overflowing population.

He subsequently sold the farms and contract to Offie (sic) Shepstone, third son of Sir Theophilus (Shepstone), who was a great authority on native land. Shepstone was a great friend of his and they were both well satisfied with the deal. A large amount of money was involved. It was not very long afterward that Shepstone found that it was not panning out to his liking. He got behind in his instalments and, finally, repudiated the deal.

It naturally meant a lawsuit that was tried before three judges in Pretoria, with General Smuts as Counsel for Shepstone and Advocate Wessels (afterward Chief Justice) for Phil. When Smuts was briefed, he told Shepstone he had not a leg to stand on but that he would sleep over the case and see whether he could find a loophole. (Smuts told this to Phil, some years afterward). Well, Shepstone’s Counsel raked up some old Roman Dutch Law which he thought might apply. The upshot was that this contention was upheld, and the judges expressed their reluctance in having to give Shepstone the benefit of the doubt. I had given evidence and was in court when the verdict was announced. Phil was called up and addressed by the senior judge, who said that he had acted most honourably throughout and made other complimentary remarks. Shepstone was called and received a considerable telling off, for the way that he had acted. The labour contract was cancelled, and Phil only received a very inadequate amount for the farms. They were 28,000 acres in extent and were bought by the Zebedela Estates, the largest citrus proposition in the world.

In 1898 Eastwood undertook a trip to the United States of America – the “Teutonic’s” manifest of 7 December indicating that P.B. Eastwood, Farmer, aged 37, had embarked at New York bound for Liverpool. When he returned to South Africa is unknown.

The years building up to the end of the 19th century were tumultuous ones. Rancour between the governments of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State and the British Government was fast spilling over into open talk of war. Eastwood’s farm in the Waterberg was smack-bang in the middle of the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek and choices would soon have to be made. On 11 October 1899 war erupted which saw an exodus of British subjects from the Republic. Where Eastwood was and what he was up to at the time is contained in the pages of his Compensation Claim, submitted to the authorities on 6 April 1903 in respect of his farms – Uitkyk and Blindefontein - in the Waterberg district.

An amount of £520 was eventually awarded to him. In a statement, he declared that the amount claimed was a fair one and the values reasonable. The cattle etc. were taken from his farms Blindefontein (or Rickertsvraag), or adjacent farms, by the Boer forces acting in the name of General Beyers (who was commanding in the Waterberg district) and Commandant Rensburg.

One Alfred William Stone was deposed whose statement read:

I live on the farm Rickertsvraag. I know P.B. Eastwood, I was managing his farms before and during the war. P.B. Eastwood left the country two weeks before the war to undergo an operation in the Colony (Cape). When he left, he left me in charge of 56 head of cattle – his own property – 16 oxen and a number of cows and calves.

On the 21st of October 1900, General Beyers sent three men who commandeered ten young cattle and gave me the receipt attached.

As a precursor to the above Eastwood, via the solicitors Rooth & Wessels, wrote to the G.O.C. Nylstroom on 11 November 1901, in which it was stated:

We have received a communication from Mr P.B. Eastwood who is a British subject informing us that he has just returned from England and has received intelligence that damage has been done to his house and property but that it is impossible for him to file a definite claim until he can come up and go into the matter.

He is also the Manager of the Northern Transvaal Lands Company, a London company, and he has also received information that their property has suffered and that the whole of their stock and livestock has been taken.

Whether or not Eastwood was in the Cape undergoing an operation (as per Stone) or in England (as per his solicitors, which is the more likely case), he was not an active participant in the Anglo-Boer War.

That he was held in high regard was obvious with his appointment as Acting Commissioner of Lands under Lord Milner, who was in charge of the post-war British Administration of the Transvaal. It was also around this time, on 4th September 1902, that Eastwood married Sara Blanche Buyskes Kuys in Pretoria. He was a 41-year-old bachelor living in Arcadia Street, Pretoria and she, a 25-year-old spinster from Caledon in the Cape Colony who was living in Beaufort West at the time of the union. The couple had two children, namely John Helperus Ritzema Eastwood (born 1907) and Wilhelmina Joyce Eastwood (born 1910).

Soon after Eastwood took himself off to run the newly created Potchefstroom Experimental Farm where his skills were greatly appreciated. The Experimental Farm in Potchefstroom was founded in 1902 on 1,087 morgen of former Potchefstroom townlands at the behest of Lord Milner.

After the advent of Union in 1910 Eastwood’s presence became redundant and he purchased and worked a farm in the Wolmaransstad area of the Transvaal.

Eastwood was a key figure in running the experimental farm which was established in Potchefstroom in 1902. Although unclear whether Eastwood actually appears in the photograph, it is speculated that the gentleman standing in his grey suit behind the two seated men in their grey suits may well be Eastwood. The photograph may have been captured by Potchefstroom-based photographer D'Astre. (Potchefstroom Museum)

War clouds were gathering once more and, on 4 August 1914, the world found itself at war on a far larger scale compared to the South African (Anglo-Boer) War twelve years before. South Africa was called upon to enter the conflict on the side of the British Empire, tasked with the “urgent Imperial service” of invading the neighbouring German South West Africa and neutralising the German communication threat to Allied shipping that then existed.

Eastwood, staunch citizen that he was, volunteered his services. On 27 January 1915, when the invasion of German South West Africa was beginning in earnest, he enlisted with the South African Service Corps, Remounts and Transport department, with the rank of Captain.

He provided his wife, of Willow Poort near Christiana as his next of kin. At 53 he was determined to give it his all. The campaign was over on 9 July 1915, and he returned to the Union. Remaining in uniform he was admitted to Kimberley Hospital in a serious condition for an appendix abscess on 22 November 1915. He gradually improved and returned to duty. On 12 December 1915, he was granted two months recuperative leave “after healing of operation wounds.”

This was a temporary reprieve in that on 17 November 1917, at the age of 56 years and 3 months, Philip Eastwood passed away at the Military Hospital in Potchefstroom whilst still on active military service. The cause of death was an intestinal obstruction which led to shock. He was the officer in charge of Animal Transport at the time. He was buried in the Military Cemetery in Potchefstroom.

As almost a postscript to his life, the London Gazette of August 1918 announced that he had been Mentioned in Despatches for “Unremitting zeal and devotion to duty. Has rendered invaluable service throughout the campaign.” – that, in a nutshell, described Philip Baily Eastwood.

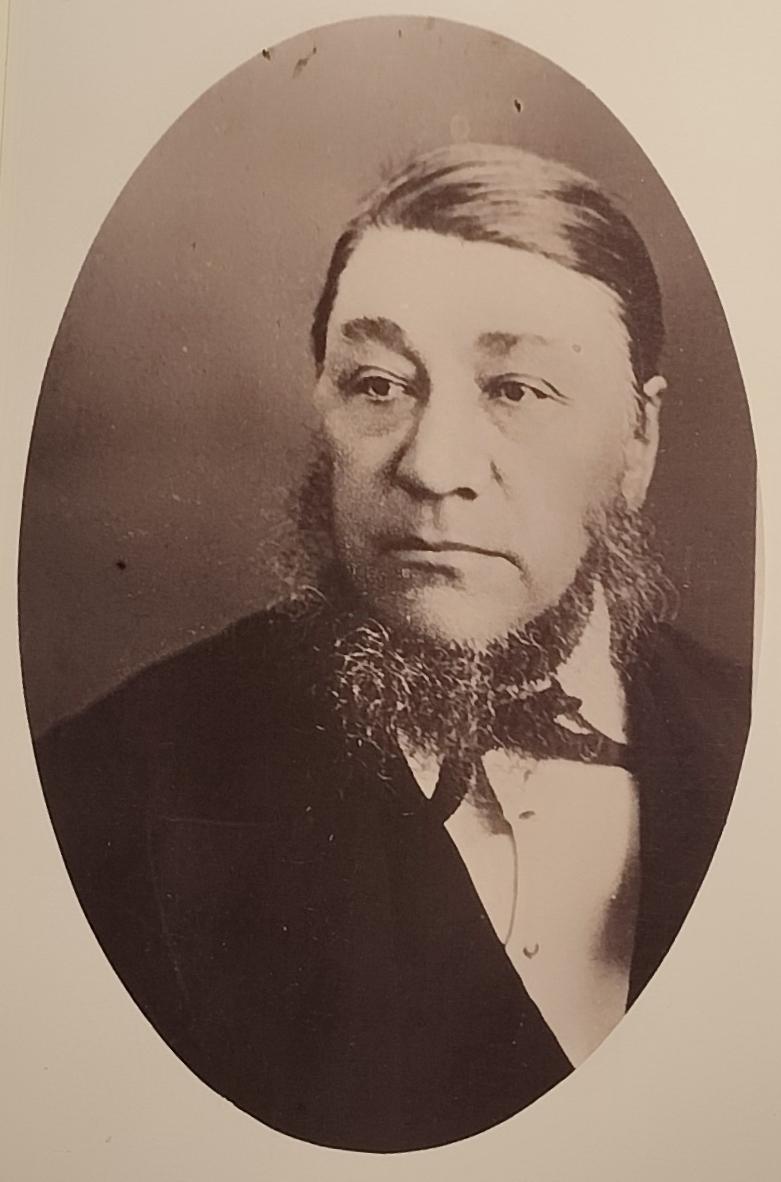

Eastwood was clearly impressed by Paul Kruger - therefore the inclusion of the Boer leader in his personal photograph album. The title states: Oom Paul - President of the SAR. Kruger was elected as the ZAR President during 1883.

Military details and medals awarded

The information captured below summarises Eastwood’s military details and medals awarded:

- Private, Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Volunteer Rifles (D.E.O.V.R.) - Basuto Gun Wars

- Captain, Transport & Remount Section, South Africa Service Corps (S.A.S.C.) – WWI

- Cape of Good Hope General Service Medal with Basutoland clasp to PTE. P.B. Eastwood. D.E.O.V. RIFLES

- 1914/15 Star to Lt. P.B. Eastwood, S.A.S.C.

- British War Medal to Capt. P.B. Eastwood

- Victory Medal to Lt. P.B. Eastwood

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Rory (2022). Philp Baily Eastwood – A Rand pioneer and soldier (www.angloboerwar.com/forum)

- Gouws, L. (2021). Street names reflect history 1 (lenniegouws.co.za)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.