Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We are honoured to publish this powerful piece of research dealing with many aspects of the outbreak of plague in Johannesburg in 1904. The piece was compiled by Tim Capon, the great grand-nephew of Emily Blake, the only nurse to die during the epidemic. The research comes at a time when historians and residents are up in arms over reports that a massive mixed use development containing over ten thousand residential units, offices, restaurants, hotels and schools is planned for the Rietfontein site.

Introduction

This paper is part of a larger work looking at the life of my great grandaunt, Emily Blake, who sailed to South Africa in May 1901 to nurse victims of the Third Plague Pandemic. Over ten years of research has gone into this project and probably a good many more will be needed before it is completed.

In this paper I hope to show that the Rietfontein Plague Hospital is possibly one of the few untouched areas that have a direct causal relationship to Mahatma Gandhi's life in South Africa; those he helped and nursed, and those he knew and died, still remain buried at the site, including my great grandaunt Emily Blake, whom he mentions in his work 'The Story Of My Experiments With Truth'. Those who died represented a cross section of South African society, from all ages, sexes and races; however, they were predominantly of Indian descent.

The recent decision to develop the site, and the lack historical information about the site and its important position in the life and work of Gandhi, is the catalyst for this work.

In this work I have used a lot of primary evidence from the period. I feel it's important that the historical record is transmitted accurately; however, the evidence also reveals a dark side, bringing language and opinions which twenty-first century readers may find both offensive and abhorrent. I wish therefore to apologise, for any offence that may be caused. However, I hope that through this evidence a better understanding of the period, of those who lived and died in it, of how important this site is to the history of Gandhi in South Africa, and of the importance of preserving the site for future generations, may be achieved.

Nurse Emily Blake 1871-1904

Plague, Gandhi and the Parliamentary Clerk's Daughter

Emily Blake was the daughter of James and Sarah Blake, of Richmond, Middlesex, Great Britain. Her father was a clerk at the Houses of Parliament and her grandfather was doorman of the House of Lords. Emily came from an educated, lower-middle-class family; her brother James would become a respected council official in Wales, while her elder sister would go on to initiate some of the first food canteens in London during World War One.

Emily was a nurse with some experience in the specialist and dangerous field of fever nursing, in a period of London's history where fevers, cholera, and typhoid were rife. For six years, in the later part of the nineteenth century, she had worked firstly in the Fountain and then later the Western Fever Hospital in London. She was recruited to become a plague nurse, as a direct response to an appeal by the Agent General of the Cape Government, who, upon the outbreak of plague in Cape Town, telegrammed London for medical support. The result was that Sir Patrick Manson, founder of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, recruited doctors and twenty nurses to sail to South Africa.

The team set sail from Southampton on the Tantallon Castle on the 20th of April, 1901. 18 days later, upon nearing the coast of South Africa, they encountered a fog bank. The ship dramatically reduced speed, but it was too late; it ran aground on the rocks off Robben Island. The passengers, crew and luggage had to be rescued before the ship was dashed upon the rocks and sank.

The team eventually arrived on the 7th of May, 1901, and proceeded to the Uitvlugt Plague Hospital, to respond to the crisis enveloping Cape Town. Later, Emily would move to work with victims of the plague outbreak in Port Elizabeth.

By 1904, she had moved again and was working as a staff nurse in the Johannesburg General Hospital.

Plague outbreak, Johannesburg, 1904

In letters to the British Medical Journal of April 1904, after the plague outbreak had occurred, Lord Milner states that plague had been taken into consideration due to previous outbreaks in the country, and that 'The public health committee of Johannesburg, acting on the advice of the medical officer (Dr Porter), resolved on the 18th of December 1902, to prepare a plague camp at Rietfontein, seven miles east of Johannesburg, for the reception of cases which might arise either in Johannesburg or the surrounding districts.'

The colonial secretary and Dr. Turner placed all the existing stores at the lazaretto at the disposal of the municipality. As a temporary measure, the old leper asylum was cleaned out and furnished for the reception of plague patients and the ground around cleared and prepared for tents. A large pavilion, formerly used for small pox, was fenced in with barbed wire and held in readiness for coloured patients. At the same time a number of preparations for the establishment of a plague camp were undertaken; a space measuring 300 feet by 900 feet, on high ground about 200 yards south of the leper asylum and half a mile east of the lazaretto, was enclosed with galvanised iron and divided into two parts, for white and coloured patients; each part being subdivided for sufferers and contacts.

In the white division, six cemented sites for marquees were prepared, and for both parts storerooms, baths, latrines, and kitchens were erected; the marquees, tents, and tarpaulins were lent by the government. The water supply was attended to; furniture, bedding, disinfectant and other necessary stores for the immediate reception of 25 patients were sent out to the camp; provisional contracts made for the requirements of 75 additional inmates; arrangements for nursing were made with a Nursing Association and a list kept of available cooks and attendants; and the use of two Army ambulances was secured.

Furthermore, the government laboratories were expanded and developed in order to enable the government to undertake the bacteriological diagnosis of the disease on an even larger scale than before. In January, 1903, the railway authorities were requested to be on the lookout for dead rats and to forward any carcasses to the laboratories for testing.

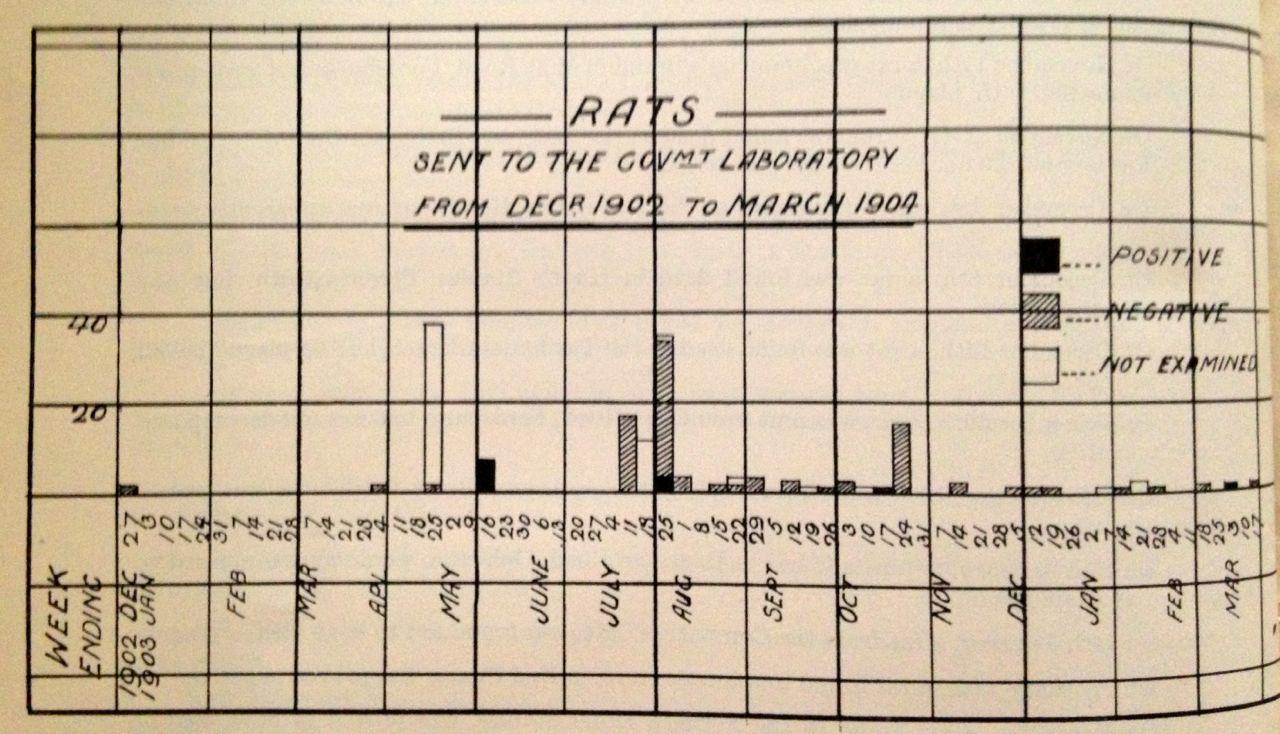

The British Medical Journal also states that from January 1903 a notable mortality was observed among the rat population, but that bacteriological examination had proved negative. In February, a circular transmitting the official description of plague issued by the English local government board was sent to all medical men in Johannesburg. In April 1903, large numbers of rats were seen dying in the market buildings, but examinations proved inconclusive.

Rats sent to the Government Laboratory from Dec 1902 to March 1904 - Plague Report (1905)

Again, in April, a dead rat was found to be carrying plague; between then and the eventual outbreak, another 13 were found to be infected. However, because no connection could be made between any two spots where they were found, the conclusion was drawn that they had been imported with foodstuffs.

By February, 1903, residents were becoming ill with pneumonia and plague-like symptoms. On February 9th, a Jewish bookkeeper developed a large bubo in his right groin, but survived. On March 21st, a Dutch Mason died suddenly of pneumonia; a week later, a native died with a large bubo in the right arm. Two weeks later, a hospital worker developed a bubo but survived; on 19th April a boy died suddenly and the medical men attending ascribed his death to plague.

On the 28th April, a Zulu man was found with swellings and was removed to the Rietfontein plague camp where he died; the medical men in attendance were in no doubt that his death was due to plague. Around the same time another patient was found with a bubo and was removed to the plague camp; he subsequently died.

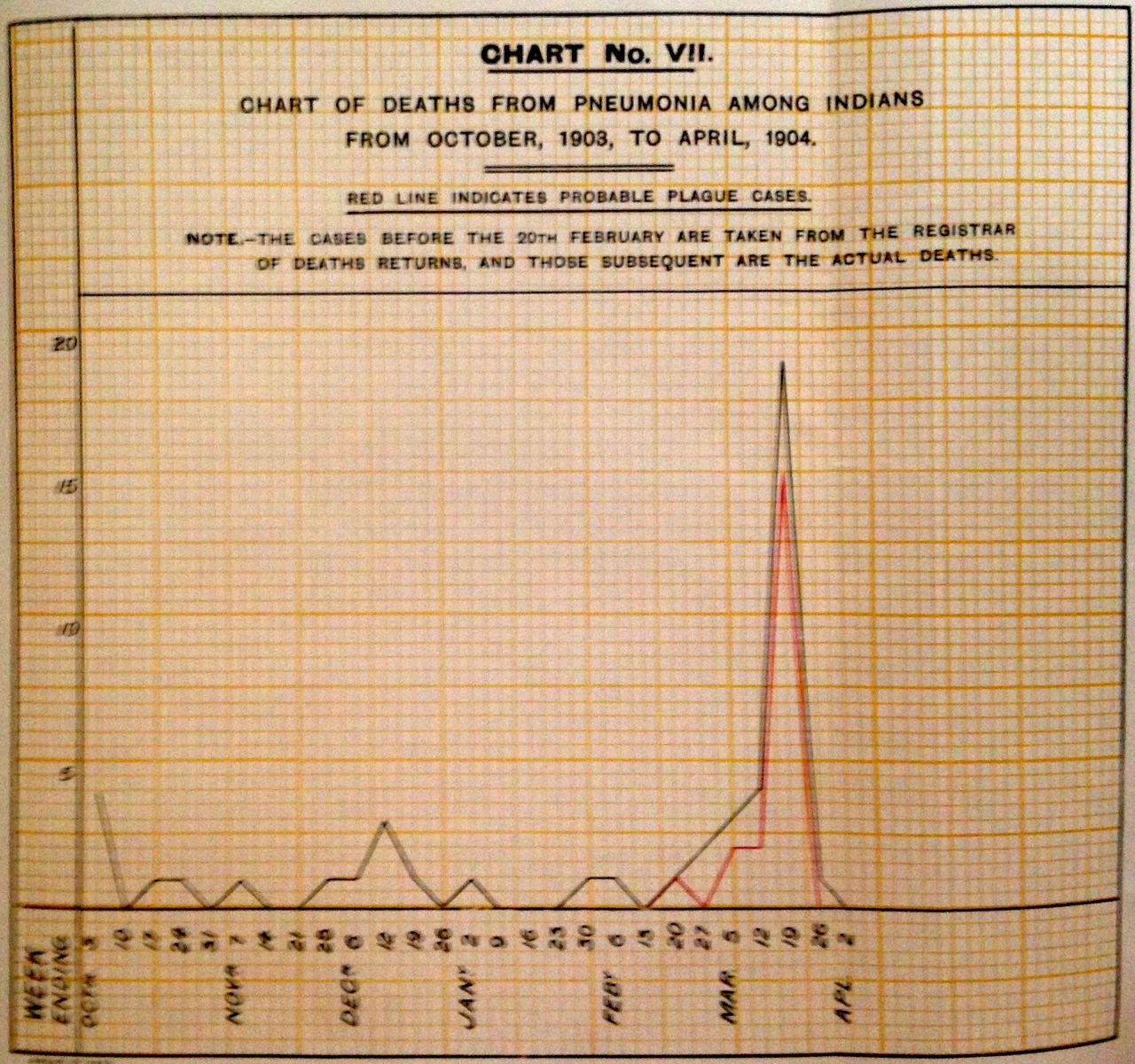

Bacteriological examination could only establish pneumonia. Once the plague was established, however, it would be shown that both pneumonic and bubonic plague were present, and that the pneumonic, the most virulent form, seems to have preceded the bubonic. A later study of deaths preceding the outbreak would show the plague had been claiming victims in the Indian community long before it was recognised and announced.

Chart of Deaths from Pneumonia among Indians from October 1903 to April 1904 (Plague Report 1905)

Thus, records show that before the plague epidemic was announced in March, 1904, symptoms of plague were already established in Johannesburg in 1903, even though it had been misdiagnosed, and that the Rietfontein plague camp had been established, resourced, and was in use prior to the main outbreak, with victims' burials already taking place there.

However, the potential for plague wasn't lost on another resident of Johannesburg, M. K Gandhi.

According to the Rand Plague Report of 1905, the Indian location in which the plague appeared was in a terrible condition. This location was included in an

area of about 150 acres which the Town Council of Johannesburg decided to appropriate as an insanitary area in March 1902; it appointed a commission to investigate possible alternative locations to which residents could be removed. Under questioning, Dr Porter, Medical Officer for Health for Johannesburg, says of the area, "It almost passes description. It consists of a congeries of narrow courtyards, containing dilapidated and dirty tin huts without adequate means of lighting and ventilation, huddled on the area and constructed without any regard to sanitary considerations of any kind." He further describes the place as a rabbit warren, and states that he considers the location's very existence as "fraught with danger to Johannesburg".

The Council wanted to move the insanitary area, which included the Indian location and the location which housed native Africans, further west beyond the city centre. However, time and again, it ran into either objections or delays: the former from residents near the proposed area (14th October, 1902), the latter as a decision was held over until after the municipal elections of 9th December, 1903, and again as it was held over from February 1904 to a proposed new date of 9th March 1905. As these delays pushed the decision further and further back, the insanitary area, for which the council were now landlords, became more overcrowded as new arrivals were squeezed in ever tighter, and became even more insanitary.

Gandhi's argument was that although the area was horrible it had become far worse since the Council had taken over its stewardship. When the Indian community owned their own stands, on 99-year leases, they had some small control over their own area; the individual stands employed men to keep the stands clean. However, even then the municipal authorities only applied rudimentary sanitary measures to help them; there were no lights or roads. Gandhi argued that when the municipal authorities took over the area, ""It was hardly likely that it would safeguard its sanitation when it was indifferent to the welfare of its residents"

Once the insanitary area was proclaimed, the municipal authorities began buying back the leases. Gandhi represented the individuals concerned who were seeking compensation. These residents, he argued, were not the usual immigrants who migrated for wealth or trade, but "ignorant, pauper agriculturalists who needed all the care and protection that could be given them". The traders and educated Indians who followed them were very few. Thus, the criminal neglect of the municipality and the ignorance of the Indian settlers conspired to render the location thoroughly insanitary.

Insanitary conditions in Brickfields in the 1890s next to 'Coolie Location' (Museum Africa)

Since the Council had taken over as landlords, any measures to improve sanitation had ceased to happen altogether, and furthermore it was pushing more and more of the newly arrived native African and Indian population, coming to Johannesburg to find work, into the area, making the overcrowding and sanitation horrendous. Gandhi further argues that "The Municipality, far from doing anything to improve the condition of the location, used the insanitation caused by their own neglect as a pretext for destroying the location and for that purpose obtained from the local legislature authority to dispossess the settlers"

From 11th February, 1904, Gandhi was writing to Dr Porter about "the shocking state of the Indian Location", where "rooms appear to be overcrowded beyond description [...], sanitary services are irregular [...] and worse than before". He went on to state: "From what I hear, I believe the mortality in the location has increased considerably, and it seems to me that, if the present state of things continues, [an] outbreak of some epidemic disease is merely a question of time".

Gandhi asked Dr Porter to visit the location. In a post-visit letter of 15th February, 1904, he wrote "I am extremely obliged to you for having paid a visit [...] and the interest you are taking in the proper sanitation of the site". However, the inspection didn't seem to have gone well: "I think that if the Town Council takes up a position of non possumus, it will be an abdication of its function [...] every minute wasted over the matter merely hastens a calamity for Johannesburg and that through no fault of British Indians". His warning to Porter is clear: "The obvious duty of dealing with this present danger of insanitation and overcrowding in the Indian Location, in my humble opinion, is not to be neglected. I feel a few hundred pounds now spent will probably cause a saving of thousands of pounds; for if, unfortunately, an epidemic breaks out now in the Location, panic will ensue and money will be spent like water in order to cure an evil which is now absolutely preventable".

However, Dr Porter seemed to take umbrage to Gandhi's letter, as Gandhi's reply of 20th February would suggest: "The only reason why I wrote the letter, to portions of which you have taken exception, was to serve the cause of sanitation, and my own countrymen. I do not withdraw anything that I have stated, because if it were necessary every one of my statements can be supported".

After his visit, Dr Porter reported to the Council:

On 13th February, accompanied by Mr Gandhi, I again inspected this place with special reference to overcrowding. This overcrowding and its insanitary consequences are such that I feel it an imperative duty to repeat formally to you what I so emphatically represented to the Insanitary Area Commission, viz. that the continued existence of the location is in my opinion fraught with the greatest danger to public health. I beg therefore most strongly to recommend that the matter be regarded as one of great urgency, that arrangements be made at the earliest possible date for the transference of this population to some other site, and if necessary they be accommodated in tents pending the erection of more permanent dwellings.

On the 1st of March, Gandhi informed Dr Porter that, in his view, plague had taken hold in the location, as the mortality rates due to pneumonia had been rising considerably. Porter disagreed, saying that no indications of plague could be found in any bacteriological examinations; however, the potential for an outbreak of an infectious disease wasn't lost on him.

On the 16th March, two days before the outbreak, Dr Porter handed the Mayor and Council leaders a letter before their meeting:

Having gathered that there is a possibility of material delay in action by the council as regards the abolition of the existing Indian Location in the Insanitary Area, I consider it my duty to remind you of the very strong terms in which I felt it necessary to represent to the Insanitary Area Commission that the continued existence of this location is, in my view, fraught with gravest danger to the public health. I also desire to recall the fact that on the 15th of February last I most strongly recommended to the Public Health Committee that this matter might be regarded as one of greater urgency and that arrangements be made at the earliest possible date for the transference of this population to some other site.

As the condition of the Indian Location has recently, chiefly on account of overcrowding, reached an even lower depth of insanitation than at the time of the sittings of the Insanitary Area Commission , I trust that I should not be misunderstood in saying that I view with the greatest concern the possibility of any further delay in doing away with this place , as in the event of an outbreak therein of epidemic disease, the control of the latter would undoubtedly be a matter of the greatest difficulty.

Personally I look upon the Public Health Committee's proposal to temporarily place an Indian Bazaar to the west of the (native) location as the best method of temporarily dealing with the pressing danger and difficulty, and although such action may not be without grounds of objection by the white residents in the vicinity such objection I venture to submit is entirely outweighed by the gain to the town at large by the removal of the present exceedingly dangerous location at Burgersdorp.

Thus the Council's reticence to make a decision lies in the fact that the white residents didn't want the Indian community living near them. This attitude would be the main factor in the causation of plague in Johannesburg, and, as would later be seen, the plague would be the catalyst used to move the Indian citizens out of the city altogether. According to a report in the London Times of March 22nd, the decision to remove the location had aroused considerable opposition, more than is suggested by the Rand Plague Commission Report.

However, it was all too late. By the 18th of March, plague had broken out in the Indian location. Gandhi sent a pencilled note to Dr Porter on March 18th, 1904, asking for help to be sent.

I understand that there are about fifteen Indians, in the condition described, in the location. Many of them paupers, one man has died and no one has removed or is in a position to remove the body [...] Will you kindly interest yourself in the matter? [...] A great deal is being done by volunteers and the patients are being attended to [...] If you will give me one of the vacant stands in the location to be used as a temporary hospital it will very much be appreciated. I believe it is the duty of the Town Council to attend to these men. The Indian community, however, will raise subscriptions and partially fit out the place. Dr Godfrey, who has just returned from Glasgow, will probably attend the patients free of charge or at a nominal fee.

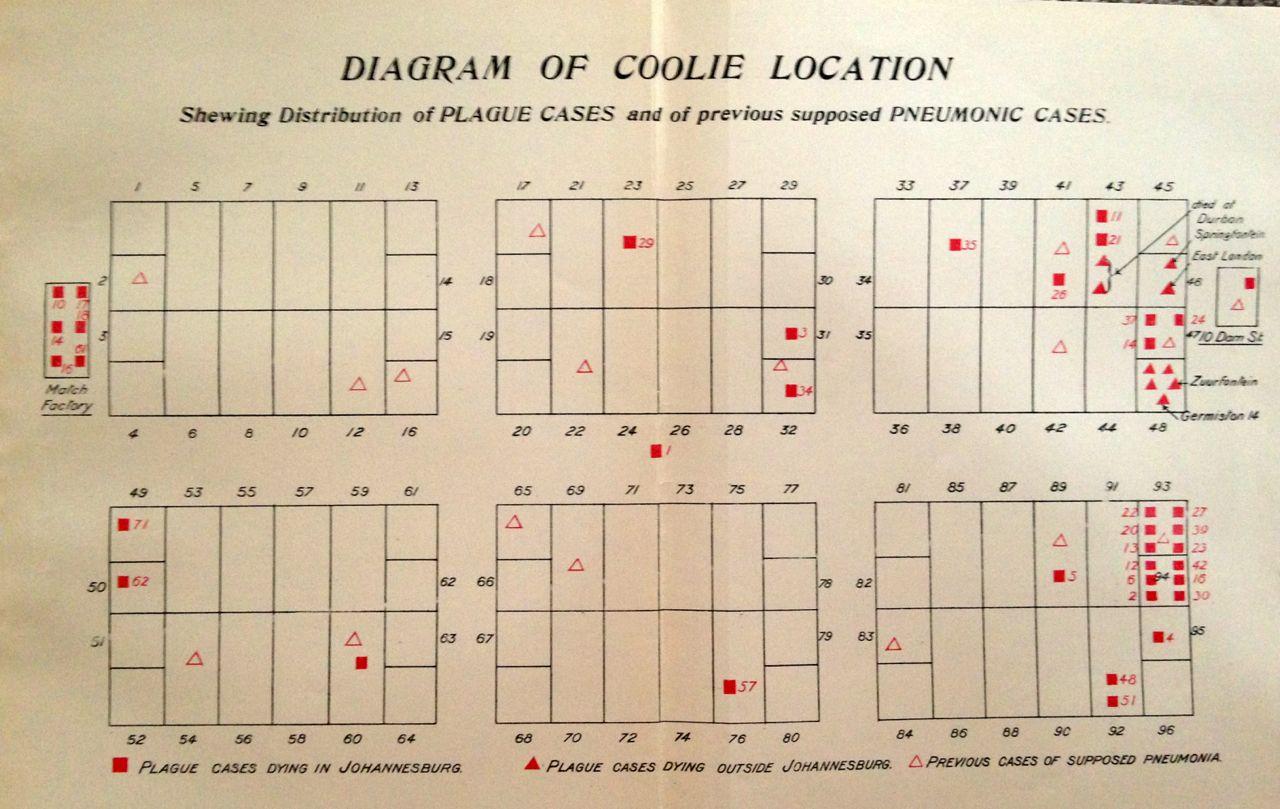

Diagram of Coolie Location (Plague Report 1905)

Gandhi went to the location and, with Sgt. Madanjit, broke open one of the vacant houses at stand 36 and relocated all the patients in there. Dr Godfrey immediately joined them but Gandhi knew that the three of them couldn't do all the nursing themselves, so he recruited four of his unmarried clerks to help him. They nursed the patients over that night.

At 6.30 am, Dr Mackenzie visited the location and found 17 dead, or dying. Specimens were taken and sent to the government laboratory, and the mortuary van removed five corpses for post-mortem examination. When Dr Mackenzie arrived at the mortuary, he found another body had been brought in from the match factory. On the same day a sick Indian had been taken to the General Hospital, suffering from pneumonia; he also died. Specimens were taken and forwarded on to the laboratory; he would be subsequently diagnosed with plague.

By noon on the 19th March, the government laboratories knew it was plague. It was therefore decided to officially announce the presence of plague in Johannesburg on the 19th of March, 1904.

The High Commissioner was informed and Mr Showers, the Commissioner of Police, was instructed to throw a cordon round the area and prevent anyone moving in or out of the area unless they had special passes. The cordon was completed at 4.00 am on Sunday 20th March.

By the end of the 19th of March, all cases were diagnosed as a type of bronchopneumonia, i.e. pneumonic plague. At that time, no enlarged glands typical of bubonic plague had been found on the victims. The first case of mixed pneumonic and bubonic plague occurred on Sunday 21st of March; the victim was a Malayan man.

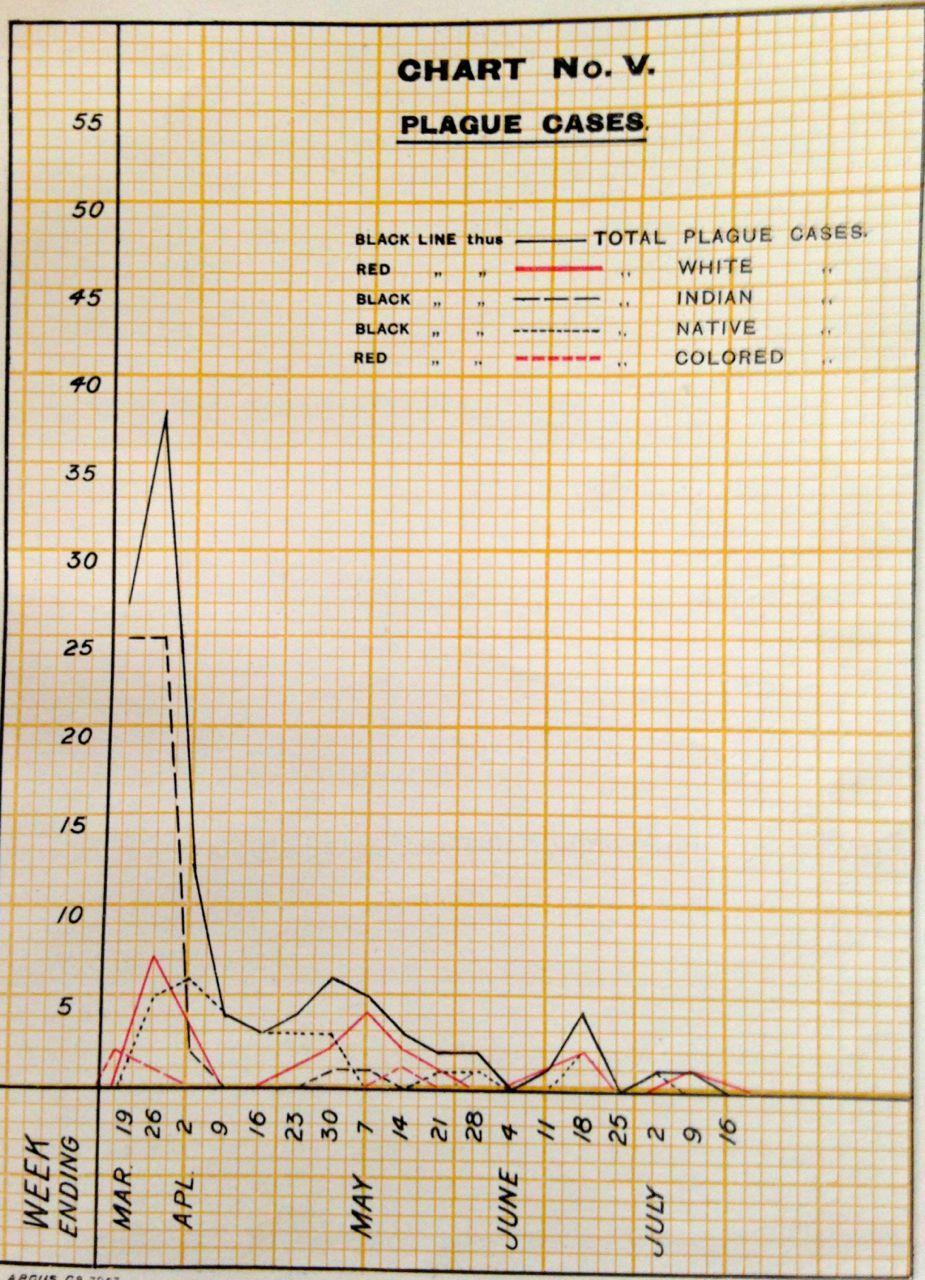

The plague then exploded; between March the 19th and March the 25th, 65 victims had been diagnosed, of which 55 had died. The heaviest day for deaths was March the 20th when 22 people died, i.e. two days after Gandhi had informed the authorities that plague was afoot in the Indian location.

Plague cases per week (Plague Report 1905)

On March 21st, 1904, just days after the outbreak began, Gandhi gave an interview to 'The Star'.

The Indian community warned the proper authorities of what were very suspicious indications about two months ago. Subsequently, another communication was sent to Dr Porter stating that plague symptoms had developed. Four days later, Mr Gandhi stated that he had received a letter from Dr Porter to the effect that the health officer had failed to find any indication in substantiation of the statement. On Friday, however, Mr Gandhi was informed that a number of Indians, dead or dying, were being dumped down in the location by rickshaws. After informing the authorities, Mr Gandhi, accompanied by Dr Godfrey, Dr Pereira and a health inspector, visited the suspected area, and, on entering a house which the Indian community had themselves isolated, discovered 14 patients.

Voluntary subscriptions had been taken up amongst the Indian community, and the patients were made comparatively comfortable under the supervision of a number of volunteer male nurses. Dr Godfrey at once took control of the improvised hospital and arranged that there should be a medical attendant present through the night. On Saturday morning, Gandhi states that the town clerk visited him and said that while he could not undertake any financial responsibility on behalf of the Town Council, he would, as requested, grant the use of the Government Entrepôt, on Station Road, as a temporary hospital [...] Dr Mackenzie, the district surgeon, would supervise the arrangements, which included provision of a nurse. Out of 25 admitted, only five were alive on Sunday night; three were subsequently transferred to the Lazaretto at Rietfontein.

The vacant building to which the patients were to be removed was the Government Entrepôt, which had previously been the customs warehouse, close to the lighting works on Station Road. It was outside of the Indian location but still within the insanitary area. It had not been cleaned by the municipal authorities, so Gandhi and his clerks cleaned up the place themselves and were given beds and other necessities by charitable Indians, and a nurse supplied by the Council.

At the same time, the house on stand 36 was closed and disinfected, and all suspects and patients were sent to the new temporary hospital. A team of municipal inspectors were detailed to the Chief Disinfector; all houses from which a patient had been taken were disinfected, and then closed. On the Sunday morning, a staff of inspectors were detailed to Dr Godfrey to carry out house-to-house inspections and to find and treat any sick they found.

Municipal rat catchers were also sent in, but, as would be later shown and confirmed by the community at the time, most of the area had become nearly rat free; no more than 12 were found, but all were plague-infected.

On the Monday morning, a team of scavengers was sent in to collect every piece of rubbish and burn it.

Writing later in his autobiography, 'The Story Of My Experiments With Truth', Gandhi recalls the nurse sent to help "carrying brandy and hospital equipment":

The nurse was a kindly lady and would fain have attended the patients but we rarely allowed her to touch them, lest she catch the contagion. We had instructions to give the patients frequent doses of brandy. The nurse even asked us to take it for precaution, just as she was doing herself. But none of us would touch it. I had no faith in its beneficial effect even for patients.

The patients were subjected to earth treatments. However, only two were saved; the other twenty died. Later, the surviving patients and the newly infected and suspected patients were removed to tents at the Rietfontein lazzaretto. Gandhi states that "in the course of a few days we learnt that the good nurse had had an attack and immediately succumbed".

The only nurse to die during the course of the plague epidemic, as outlined in the Rand Plague Report of 1905, which lists all the plague deaths, was Emily Blake. Indeed, upon her death, the Council meeting minutes record that she had immediately volunteered upon the outbreak of the epidemic, and, given her previous extensive experience as first a Fever Nurse in England and then a Plague Nurse in Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, it was in character for her to be in the thick of it from the outset.

Once patients were being transported from the municipal Entrepôt hospital to the Rietfontein Plague Camp, Emily would move to the Rietfontein Plague Camp to deal with the incoming plague patients and suspects, around the 22nd of March. It was while at Rietfontein that she was infected with pneumonic plague, after kissing one of the infected children of Dr Marais, and died on the 27th of March.

Dr Marais, his wife and three of their four children all died early in the epidemic from pneumonic plague.

Dr Marais, who died on the 17th March, had been attending cases of pneumonia in the Indian location just prior to the announcement of plague, when he contracted it himself and passed it on to his wife who died on the 21st March, then to their children, and a male lodger, Mr A.R. McNeil, who died on the 22nd March. The plague infection chart in the Rand Plague Committee Report shows direct transmission from one of the children, all of whom were removed to the Rietfontein camp on the 22nd of March, and into Emily Blake's care.

The South African Medical Record of April 1904 records that her death at the Rietfontein Hospital was the cause of much sorrow. An appeal set up to bury her raised £42, around £4,458 in today's money; she was buried in a lead coffin in the grounds of the Rietfontein Hospital, where she still lies.

The Grave of Emily Blake (Sarah Welham)

The Rand Plague Committee Report states of Emily's death:

The nurse in question had been nursing plague patients in both Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, and it appears that she had acquired a contempt for the disease, which the familiarity breeds, and had treated the pneumonic cases as bubonic cases. Certainly she kissed the children [...] She was one of the first volunteers and an excellent nurse, and in view of her previous experience and the usually accepted idea that plague is not a highly infectious disease, it is impossible for anyone to hold any feeling but one of deep regret.

So, between 20th of March, once a cordon had been placed round the Indian location, until the 1st of April, when the Indian location had been evacuated, infected patients and contacts were moved initially to the Government Entrepôt in the insanitary area, then conveyed by ambulances to the Rietfontein Plague Camp.

On the 22nd of March, the Rand Plague Commission was constituted and began to issue instructions following government-published plague regulations. The Rand Plague Committee consisted of ten members from Johannesburg and representatives from the Witwatersrand area. At a special meeting, £5000 was allocated to the board for initial expenditures. One of their first acts after appointing staff was to implement the recommendations of the Durban Congress. People termed as contacts were kept under observation, suspects were isolated in the suspect camp adjoining the Plague Camp at Rietfontein and infected victims were sent over to the Plague Camp straight away.

Rietfontein Plague Camp

To get an understanding of the medical process it is worth quoting the Rand Plague Committee's Report at length.

The plague camp at Rietfontein being seven and a half miles from Johannesburg, it was necessary to have a receiving hospital. A house in Station Road within the insanitary area was therefore obtained and fitted up. It was divided into two portions for the reception of suspects on one side and for plague patients on the other. So far as possible, Asiatics and natives were further separated [...] and staffed on similar lines, the difference being that the attendants were men not women.

The Ambulance staff as well as the number of Ambulances was very considerably increased. Each Ambulance was accompanied by a white driver as well as by a native attendant. Separate Ambulances were kept for white patients. It was found convenient to have two methods of procedure in respect of white and Coloured patients respectively. Any white patients, whether suspects or plague patients, were removed direct to Rietfontein from their places of residence and did not go to the receiving hospital. All coloured patients were removed to the receiving hospital and remained there until the Ambulance left for Rietfontein.

The Rand Plague Report thus makes clear that all suspects and infected patients, whether taken to the receiving hospital or not, were removed to the Rietfontein Plague Camp, where they were either watched, or nursed until they recovered or died.

The Report continues,

As there was only one plague camp for the Witwatersrand area, a railway ambulance was necessary. A box truck was therefore placed at the disposal of the Plague Committee and fitted up with stretcher beds. When a coloured patient was transferred from an outside district to Rietfontein, after leaving the railway ambulance he was taken to the receiving hospital, and from there he was taken to his final destination.

On the development of the Plague Camp, the Report states:

In view of the possibility of the outbreak of plague in the Witwatersrand, the Town Council of Johannesburg, in conjunction with the government, had, in December 1902, selected a site measuring 200 yards by 300 yards on the farm Rietfontein, which was the property of the government and on part of which the Lazaretto and incurable home were situated for a plague camp. The Town Council had fenced this site round, had made concrete floors for marquee tents and had erected a kitchen, three stores, four bathrooms and baths and latrines, and provided a water supply and equipment for the immediate reception of twenty patients at a total cost of £2,655. These preliminary preparations were as complete as could be reasonably be expected, but it was found necessary to make some important additions and alterations.

Plans were immediately passed by the Rand Plague Committee for the further equipment of the camp. These plans were drawn out by the town engineer after consultation with doctors Mackenzie, Montgomery, and the Medical Officer of Health to the Rand Plague Committee. Although the want of the additions and alterations subsequently made in the camp did not affect the mortality of the cases or the comfort of the patients, there was not sufficient accommodation for the staff, and during the early period the nurses had to perform their duties under extremely uncomfortable circumstances. The tents which were obtained from the army were not sound and this report cannot be written without containing an appreciation of the abnegation of the nursing staff who volunteered to go to Rietfontein and nurse the patients at a time when they literally had not a rain proof roof over their heads.

The camp as constructed by the Rand Plague Committee was divided into two parts, separated by a corrugated iron fence, the part on the left of the main entrance being for plague patients and that on the right for suspects. Each camp was further subdivided into three divisions for whites, Asiatics and natives, by barbed wire [...] A receiving block was built at the junction of the two camps for the admission and discharge of the patients, a division being made in this in order to provide bathrooms for white and coloured cases separately.

Arrangements were made whereby the administrative camp, the suspect camp, and the plague camp were each separate entities, each having kitchens, bathrooms, etc. The camp was opened and occupied on Tuesday 22nd March and closed down on the 1st of August. During this time, 206 patients were admitted and treated.

The Report then makes clear that all plague patients and suspects were received and treated at the Rietfontein camp. It was integral to the Council's response that suspects and infected patients were isolated away from the town as quickly as possible. All fatalities had post- mortems performed on them. Initially these happened at the General Hospital, but very quickly a mortuary was opened away from the city, probably much closer to the plague camp. All those who died seem to have been buried at the plague camp.

The Indian location had now had a cordon placed around it and the area was fenced in with a corrugated iron fence. Gandhi states, "The location was put under a strong guard, passage in and out being made impossible without permission. My co-workers and I had free permits of entry and exit."

Gandhi further observes that "The people were in a terrible fright, but my constant presence was a consolation to them". Although now no longer nursing the plague patients, his time was taken up helping the community, many of whom had buried their savings, which now had to be recovered. With his help, the monies were accounted for and disinfected, and a friendly bank manager found who would accept large amounts of coinage and open up accounts for the owners. In total, he states, £60,000 was collected.

The next response of the Rand Plague Committee of the Town Council was to remove the residents of the Indian location as quickly as possible from the centre of Johannesburg. The Committee's reasoning was that the area wasn't fit for habitation, and that given the possible widespread nature of the plague, it was wiser to treat all the inhabitants as suspects rather than contacts. Containing them out of town would remove them from an infected area, allow better observation of the great number of possible contacts, and allow the Council the opportunity to destroy the perceived seat of the plague.

It was decided to remove the location to a farm called Klipspruit, situated about 12 miles from the centre of Johannesburg. On March 23rd, 100 medically inspected labourers were sent out to erect tents and dig latrines at the site. On March 24th, 360 Indians were dispatched to the site along with a Dr McMunn, who was placed in medical charge. By March 30th all 3,100 inhabitants had been removed to Klipspruit. "This city under canvas looked like a military camp," exclaimed Gandhi.

Ten days later, the Indian location was put to flame, a galvanised iron fence had been sunk to a depth of 18 inches around the location, and hunts were organised to destroy all the animals within the area. Once completed the area was handed over to the Chief of the Fire Brigade for destruction; the wood and iron houses were soaked in kerosene and fired. The area was fired on the outside and burnt inwards. When it was over it was found that there were no rat carcasses to be found; no rats had run towards the iron fence.

At first the Klipspruit camp was essentially a contact camp. None of the inhabitants were allowed to go outside under any pretext. According to the Rand Plague Committee Report, only one case of plague occurred in the camp. The camp was closed for 12 days after the death, and then it became an accommodation camp, where the inhabitants had some independent, though restricted, movement. Daily passes were issued to allow inhabitants to go and look for accommodation in the city. However, before anyone could move in, inspectors had to be satisfied that the premises was fit for habitation; if they weren't, instructions were issued for improvements, and the premises then had to be reinspected. Only once the inspectors were satisfied was a permit to reside issued. As the Report puts it, ""No one who had once been taken to Klipspruit was allowed to leave the camp permanently until he had shown that he was returning to a proper residence"".

The camp, according to Gandhi, became like a prison camp: residents had to return to the camp before 8.30pm or fines would be imposed, and repetitions of lateness could lead to imprisonment; movement outside of the Witwatersrand area was prohibited unless individuals had a health certificate; evidence had to be provided as to the suitability of accommodation that the applicant wanted to move to, and the medical inspectors of the camp had to be in agreement with the medical inspectors of the area concerned that the accommodation was suitable. These restrictions effectively isolated the community to Klipspruit and Johannesburg, and ensured that any movement was restricted on sanitary grounds. Movement was further restricted when the railways declined to issue tickets to Indians.

The move to Klipspruit was justified by the Council as a way of isolating potential plague contacts, while the area it felt was responsible for the plague was destroyed. However, as in the case of the Cape Town plague, it subsequently became a means to isolate and control the area's non-white inhabitants, in defined, manageable locations. Plague, and the need for sanitation, were used as justifications, to control housing and movement of all non-white inhabitants, a process that would continue and worsen over subsequent decades.

Rand Plague Committee - Plague Report Front Cover

Conclusion

From the 19th of March to the plague's last death on the 9th of July, and its eventual announced end on the 16th July, 1904, 113 cases of plague had been identified; out of those, 82 had died. The greatest death toll took place between March and April, when cases were mainly of the pneumonic type. Over the period of the plague epidemic, there were 67 cases of pneumonic plague, 65 of which were fatal, compared to 38 cases of the bubonic type, of which nine were fatal. Of the six cases of mixed pneumonic-bubonic plague, all were fatal, as were two cases of septicaemia.

The greatest mortality occurred within those infected with pneumonic plague. The majority of this group came from the Indian location and died within the first three weeks of the epidemic. By the third week, the pneumonic strain had run its course and been replaced by the bubonic form. The Rand Plague Committee concluded that most of the pneumonic cases resulted from contact with another infected person, while those of the bubonic variety were transferred by infected rats. The mortality rate of the 113 cases was 72.5 per cent, with 94 per cent of those coming from the Indian community.

Subsequent investigation of the register of death returns would confirm Gandhi's suspicion that pneumonic plague had been present in the Indian location from around the beginning of January 1904, as well as his initial view that if the municipality had spent some money rectifying the situation sooner, it wouldn't have cost them thousands later.

The plague in Johannesburg occurred because the Indian location was ignored by civic authorities and allowed to become insanitary. When it became evident that something needed to be done, the Town Council expropriated the area, but then failed to follow through by either putting in sanitary facilities, or moving the location. Instead, the Council seem to have been swayed, firstly by white objections to having the location moved within closer proximity to them, and, secondly, by the fear of losing votes during an election period if a decision was made. Instead the location was left to become more overcrowded and more insanitary, despite medical opinion that if left unmanaged it could endanger all of Johannesburg.

When inaction became impossible, the authorities' reaction was slow, and initially evasive, despite the fact that the isolation hospital at the Rietfontein farm had been established in 1903. However, once the Plague Committee had been established, it isolated the infected area and established a medical process to deal with the emergency. This involved isolating the community, throwing a police cordon around the area, and the eventual removal of the community to a site which had once served as a sewage farm. This, in turn, led to the community being isolated and its movement controlled by municipal authorities. Thus the plague and the cause of sanitation served as a pretext for the racial segregation of communities.

Gandhi's role during the plague emergency should not be understated. He had been a respected member of the community since his arrival in Johannesburg and represented the community in its compensation claims against the Council after it had expropriated the Indian location. It was he who raised the alarm early in 1904 that an epidemic was certain to occur, and, in his view, was already occurring, a position which was subsequently proved to be correct.

When plague hit, he rallied and supported the Indian community, who themselves contributed medical support, money and hospital facilities. He took charge of the situation, found premises to put the initial infected patients in, and nursed the first victims. He was the contact man between the Council authorities and the Indian community, which the Rand Plague Committee grudgingly recognised; it was he who undoubtedly calmed the situation within the community, helping to ensure the plague was contained and isolated and the community supported. Despite his obvious objections, he did all he could to help the Council move the residents to Klipspruit, though it was clear that the plague was being used as an excuse to move the Indian community out of the centre of Johannesburg.

The Rietfontein plague hospital had been established in 1903, as a response to earlier plague epidemics in Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. When plague occurred in Johannesburg, the hospital was put into action within days of the outbreak, with all suspected plague cases removed from Johannesburg and isolated and monitored there until they were either released or treated for plague. Those that succumbed had post-mortems performed on them prior to being buried in the grounds of the hospital.

Thus, though it cannot be said that Gandhi visited the Rietfontein plague camp, many of his community whom he knew, nursed and helped did. They were treated at the hospital. Many still lie there in unmarked graves, which stand testament to a period of Johannesburg's history when Gandhi helped save not just the Indian community, but also the city itself.

The camp is also the last resting place of Emily Blake, the nurse who worked with Gandhi and the Indian community, and who helped prevent the spread of plague to the rest of Johannesburg. She came to South Africa to help all victims - black, white, rich, or poor. It is now time for the citizens of Johannesburg to help Emily and protect her last resting place, as well as those of the people she gave her life trying to help.

Dedicated to all those who died in the plague epidemic Johannesburg February - July, 1904

Bibliography

- Rand Plague Committee 'Report upon the outbreak of plague on the Witwatersrand, March 18th to July 31st 1904

- Johannesburg: Argus Printing and Publishing Company, LTD, 1905

- M.K Gandhi 'Story of my Experiments With Truth,

- M.K Gandhi, 'Indian Opinion, 1904

- M Echenberg, Plague Ports:The Global Urban Impact of Bubonic Plague 1894-1901

- British Medical Journal 1904

- South African Medical Journal 1904

- The London Times 1904

- The Star Newspaper 1904

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.