Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 1901 the Duke of Cornwall and York – the future King George V – and his wife embarked on the longest official tour ever undertaken by the British Royal family. The tour lasted for nearly eight months and most of it was spent in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, with brief calls at Gibraltar, Malta, Aden, Ceylon, Singapore and Mauritius. They travelled almost 50 000 miles.

It became one of the great media events of its day and was viewed by contemporaries as a ceremonial occasion of great and lasting importance. At the time it was viewed as being “undertaken at the express desire of Queen Victoria, as a mark of special appreciation for the part her colonies had played in the hour of the Empire’s need.” However, the truth was much more complex. Her death in January 1901 changed the attitude of Edward VII, once he became king, and he did not want the tour to proceed. Eventually it was agreed that the tour would go ahead, so long as Joseph Chamberlain (Colonial Secretary) would guarantee that there was no danger to the heir to the throne.

George and his wife left Britain in mid March. He was not particularly enthusiastic about visiting South Africa and at his request John Anderson, the Colonial official accompanying the royal party, wrote to Chamberlain from Aden in early May, with a request to cancel the visit to South Africa as there was a “serious outbreak of plague” in Cape Town. Chamberlain convinced them that the tour should continue, as it would create a bad impression if it appeared that the trip was cancelled due to fear, as no member of the Royal Family was supposed to be afraid. It was agreed that the Duke would go to Simon’s Town, but would not land unless the plague had dissipated. Medical experts who were consulted pointed out that the risk was insignificant and that by August, when he was due to arrive, that the epidemic would be over. It was finally agreed that brief visits would be made to the Cape and Natal.

Durban during the Royal Tour (Talana Museum)

There were a number of advantages to the tour:

- It was beginning to become more difficult to raise a significant number of troops from the colonies, as they were getting tired of the war against the Boers and this would, hopefully, strengthen their commitment to the war.

- As the war dragged on and the number of South African and colonial troops continued to expand, the Royal tour could express the gratitude of the Imperial government and the Crown for their participation.

- There was criticism in Britain at the cost of the war in terms of men and money.

- Political events in the Cape in December 1900 shook Chamberlain’s confidence.

- It could be used to denounce the pro-Boers in Britain.

- It could be used to persuade the Boers to abandon a war they could not win and possibly begin a process of reconciliation between the Afrikaners and the British.

It was agreed that a special medal would be awarded to the colonial troops for service in South Africa and that George would personally present the medals. This meant that the military ceremonies surrounding the tour assumed an unusual importance in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, but a low key was called for in South Africa.

The ceremonies for the medal presentation in Melbourne set the pattern for the rest of the tour. The first award on 8 May in Government House saw soldiers arriving in a variety of uniforms and 17 officers and 462 men were awarded their Queen’s South African war medal.

On 10 May 14, 314 men, including 4,490 cadets, paraded before the Duke and Duchess. Despite rain 80 - 100 000 spectators attended the review.

In Sydney 8 500 troops from New South Wales were presented with their medals within an hour and a half. A crowd of 150 000 attended the ceremony.

When the Constitution of Australia came into force, on 1 January 1901, the 6 British colonies collectively became states of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Duke opened the first Commonwealth Parliament in Melbourne on 9 May, 1901. Thousands of people watched the royal procession as it made its way through the streets of the city to the Exhibition Building where the ceremony was witnessed by 12 000 invited guests.

The Royal party arrived in Natal on 13 August and although the visit would be brief – only 53 hours – and the request for a visit to Ladysmith, by the Duke was cancelled at the last moment.

The planned visits to Pietermaritzburg and Durban, had resulted in crews working for weeks to erect ceremonial arches and decorations on buildings and along streets. Government House had extensive alterations and repairs undertaken for the 2 nights that the Duke and Duchess would spend there.

Durban Victory Arch (Talana Museum)

Durban Town Hall decorated for the visit (Talana Museum)

In Pietermaritzburg over 8 000 flags were distributed to school children and a further 25 000 used to decorate the streets. Many private individuals also decorated their homes and businesses. Unfortunately the night before the visit, torrential rain destroyed many of the decorations.

The rain continued for the four hours the Duke spent in Durban, but this did not deter 50 000 people from lining the streets. Special stands had been built to hold 10 000 Sunday school children (including segregated stands for 1790 Indian and 1055 native children). One of the stands was so overpacked that it collapsed.

Thousands line the streets in Durban (Talana Museum)

The main ceremony, lasting 15 minutes, took place at Stanley Park, where a royal pavilion had been built, containing 2 models of the coronation chair and seating for 2 000 of the prominent and distinguished business people of the city.

After an address by the town council and various local organisations, the Duke thanked the people of Natal for their loyalty and patriotism and expressed his sympathy for those who mourned the loss of their loved ones.

After lunch in the Royal Hotel, the women of Durban presented the Duchess with a table gong. This was made of polished Natal red ivory wood with polished ivory tusks supporting 3 pom pom shells, engraved Talani, Ladysmith and Harts Hill.

They then drove off along densely packed streets to the railway station for the trip to Pietermaritzburg. The fireworks display in Durban that night, watched by 20 000 people, included images of the royal family, Lord Kitchener and other British generals serving in the war.

The next day in Pietermaritzburg, the weather had cleared and the Duke opened the newly completed City Hall with a gold key (which he was given as a souvenir). Addresses were presented from the city council, also one from Johannesburg and replies made.

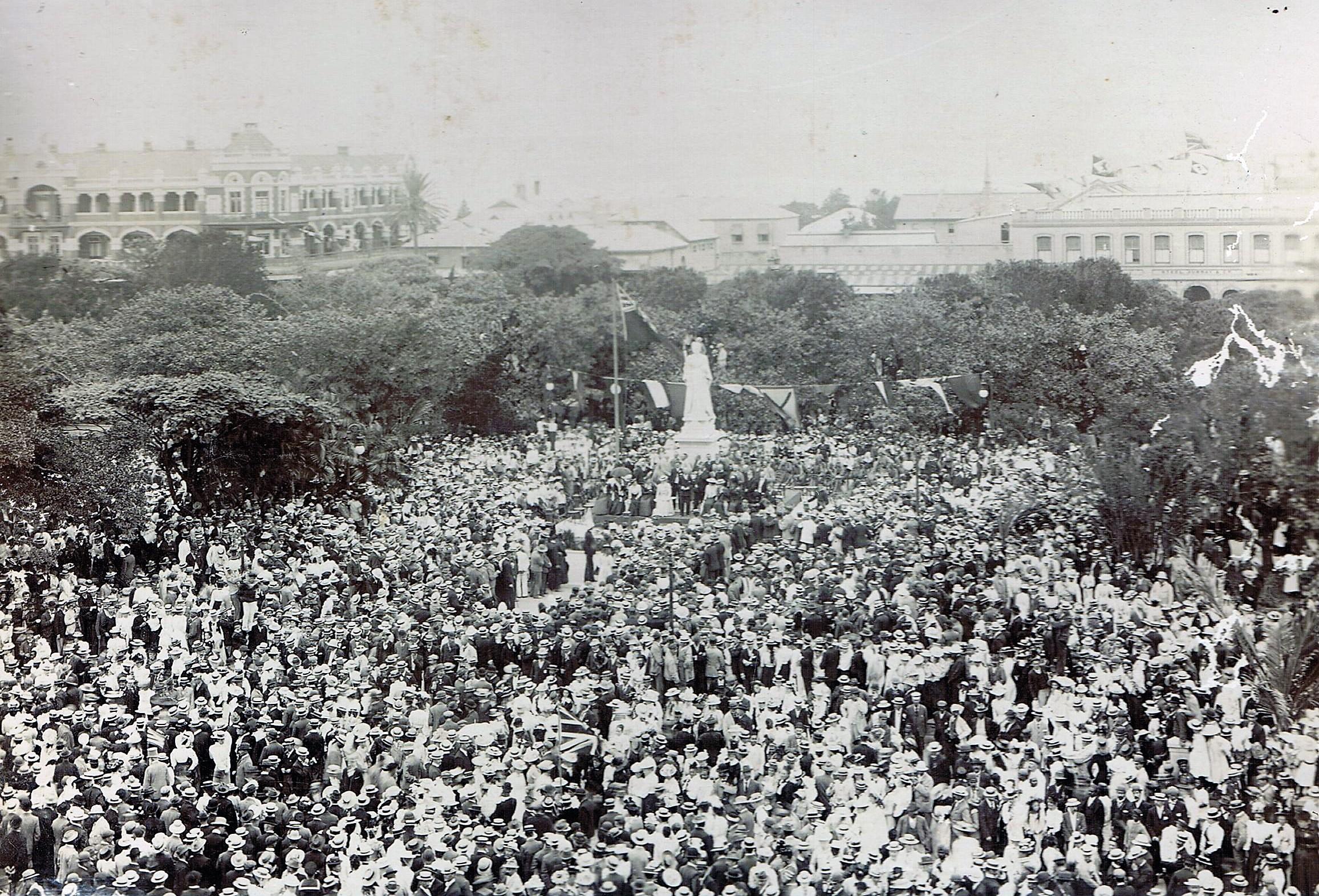

Crowds gather in Pietermaritzburg (Talana Museum)

The Duchess unveiled a mural tablet in memory of the Natal Volunteers who had fallen during the war.

After lunch the Duke presented 8 VC’s and a substantial number of DSO’s to Imperial and Colonial troops at a function in the municipal park attended by over 10 000 members of the public. He did not present the colonial volunteers with their South African medals, as the War Office was concerned that there would be jealousy among the Imperial troops, as they were not entitled to them. The final event was a Zulu war dance with 200-300 Zulus in full ceremonial dress and their special welcome to the Duke.

The next morning on their return to Durban, they inspected one of the Princess Christian hospital trains, which had arrived that morning from Pretoria, carrying wounded troops.

They also visited one of the hospital ships before boarding their own ship and setting sail for Simon’s Town.

Travelling from Simon’s Town to Cape Town by train, which made no stops, they were warmly welcomed by crowds at each station, crossing or house along the line.

The reception and program in Cape Town was much more elaborate than in Natal, as it was deemed to be the national, rather than colonial reception. After receiving nearly 100 addresses from municipalities and organisations in the colony, at the afternoon reception, they then attended an official dinner that evening – with more speeches and addresses. The Duke and Duchess had already endured several months of a succession of similar festivities in Australia, New Zealand and now South Africa. They must have been weary of such affairs; but they gallantly faced the bombardment of addresses and speeches of welcome and the many more to come in Canada.

The following morning the Duke met 23 native chiefs, including Chief Lerothodi, the paramount chief of the Basuto’s. He was given special attention, due to his support in refusing supplies to the Boers and in guarding the Basutoland frontier.

The rest of the day was a trip through the suburbs of Cape Town with lunch at Groote Schuur. Everywhere roads were lined with people, flags decorations and arches. Visits included Salt River, Woodstock, Mowbray, Rondebosch, Claremont, Wynberg, Green Point and Sea Point. A whistle stop trip of note.

The next day, Wednesday 23 August, at the annual conferring of degrees at the University of the Cape of Good Hope (today UNISA), the Duke was presented with an honorary degree and installed as Chancellor.

Thereafter they attended a children’s concert and were presented with 3 Basuto ponies as gifts for their children – the funds raised by a subscription of 1-5 shillings from the school children of the Colony. Not quite so easy to pack. Thank goodness customs were a lot more flexible then with taking animals from one country to another.

This was followed by a procession of Allegorical cars, resembling the Lord Mayor of London’s show. At the head of the parade was Long Cecil – the gun made in the Kimberley workshops, to assist with the defence of the town. This was followed by traction engines pulling trailers depicting the agricultural products of the colony, the Oudtshoorn car with a male, female and 2 baby ostriches (all specially killed and stuffed for the occasion!), Paarl depicted making wine, Kalk Bay a fishing boat and the Kimberley vehicle an example of diamond washing, with a further 6 trailers depicting the history of the colonial railways.

That evening the Duke conferred knighthoods and other honours on prominent colonials at a dinner at Government House. The next day, Thursday they laid foundation stones – the Duchess for a nurses home attached to Somerset hospital, the Duke for the new Anglican Cathedral (to be known as St George’s) and made a personal donation of 100 guineas to the Cathedral fund.

In British pounds that would be worth just over £3 000 today and if you convert to Rands that would be about R70 000 – not a bad contribution.

On Friday they returned by train to Simon’s Town, where the train stopped only once at Muizenberg for 2½ min for an address by Sir Gordon Sprigg, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. Thank goodness they didn’t have long winded politicians.

Old photo of Muizenberg Railway Station

The school children on the station didn’t have time to finish their repertoire of songs. The Duchess was presented with 2 bouquets of flowers, one being entirely of Cape wildflowers - and the train was on its way.

That afternoon they met a delegation of Boer prisoners confined in Bellevue camp, and were delighted with their gifts of serviette rings made from Kruger coins. They then boarded their ship and sailed for Canada and the rest of their tour. Mr Melton Prior, the war correspondent and artist of the Illustrated London News, who had recorded so much of the Anglo Zulu and Anglo Boer Wars, accompanied them for the Canadian part of the tour.

Did the tour have the intended effect in South Africa?

There had been an outpouring of support along their route – but they only visited 2 cities in Natal and Cape Town and its environs. Questions were asked whether it was appropriate to spend huge sums of money in the middle of a war, when the country was on the verge of ruin and thousands of people were starving. The money was spent on decorations, flags, meals, parades and in Cape Town all of those in hospitals, asylums, homes and other institutions received a special meal during the visit.

Flags flying in Durban (Talana Museum)

The city of Cape Town donated £500 towards the establishment of engineering at the College of South Africa.

Many organisations raised funds to purchase the gifts presented to the Royal couple. One of the groups the Ladies Reception committee raised £722. After purchasing all the gifts they had £350 left over, which was used to endow a bed in Somerset hospital.

The press was lyrical at times in its reporting about the long term benefits of the visit. Although it did not create a sense of an Imperial South African identity, it did contribute to it. Within 9 years South Africa would become a self governing dominion under the British Crown. Royal visitors to South Africa in the next 50 years would be warmly welcomed.

Gifts presented to the couple included:

- A magnificent black ostrich feather fan mounted and gold stems and decorated with diamonds,

- A cabinet made of colonial woods,

- Paperknife with a blade of ivory and handle of gold, decorated with diamonds, rubies and sapphires,

- Blue morocco portfolio of 50 specimens of the wild flowers of the Cape colony,

- The people of the Hottentots Hollands area raised the money to purchase a painting by a South African artist of “Lengthening Shadows on the shore of False Bay” which had been exhibited at the Royal Academy,

- The “Native Chiefs” presented them with karosses of tiger, leopard, and jackal skins, shields, assegais and beadwork,

- The Indian community presented the Duke with an ivory walking stick with the handle mounted in gold and diamonds with a Star of India formed of Burmese rubies and the Duchess a brush, comb and mirror carved in ivory.

- The women of Paarl gave them a miniature wine barrel with the hoops, tap and a shield made of gold,

- The bouquet presented to the Duchess on her arrival in Cape Town was in a holder of gold with 7 South African rubies,

- A parcel of 700 diamonds weighing 261½ carats.

Not sure I have anything to add about all that!

About the author: Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. Since 1983 as curator, Pam McFadden has developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. As part of the museum collections she has collected and created an extensive museum archive, that holds many treasures.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.