Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The tragedy of the present day Migrant Crisis caused by the Syrian Civil War has an earlier precedent which occurred in the late seventeenth century when the King of France – Louis XIV (the Sun King) revoked the Edict of Nantes (a law protecting religious tolerance). It was on the 22nd October 1685 that the King formally outlawed the Protestant religion in France, however, prior to that date the Huguenots (French Calvinists) had been persecuted rather like the Jews were in pre-war NAZI Germany. The King’s aim was to end the schism between Catholics and Protestants and bring back into the Papal fold people considered to be Heretics. Many Protestants were converted to Catholicism at the point of the sword, but the King’s repression did not destroy the faith and large numbers decided to flee France even though it was made illegal to do so.

Even before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, many Protestant families had immigrated to the United Provinces of the Netherlands where they met with greater religious open-mindedness and where they found gainful employment. The Revocation turned the flow of refugees from a trickle into a flood and it was soon realised that the Netherlands could not absorb all those fleeing France. Fortunately for the Huguenots they were welcomed by other Protestant countries in Northern Europe, as they were known to be hard working and skilled and thus would be an asset to those countries.

It is reckoned of the Huguenot Exodus of 210 000 people (roughly a quarter of their population): 80 000 would settle in the Netherlands, 50 000 in Britain, 43 000 in the Protestant States of Germany, 20 000 in Switzerland, 10 000 in Ireland and 2000 would go to Denmark, Sweden and Russia. A few thousand more would seek a new life in the colonies of the Dutch and the British and 200 or so of that number would be settled, by the Dutch East India Co. in the fledgling Colony of the Cape of Good Hope (The Cape).

The Cape sea route was first discovered by the Portuguese, when Bartolemeu Dias rounded The Cape in 1488 with a small fleet of three Caravels and although he only got as far as Algoa Bay, where he raised a wooden cross, before turning back, he had (unbeknown to himself at the time) solved the problem of finding a sea route to the East which would cut out the Arab middlemen who controlled the land routes. By 1600 the Portuguese could no longer retain there trade monopoly with the East and the Dutch, English and French became their rivals.

Laying anchor in the bay beneath Table Mountain would become a regular occurrence for mariners going round the Cape, no matter what nationality, but it would be the Dutch East India Co. that would build a permanent revictualling station for their ships plying between Europe and the East Indies. On the 6th April 1652, Jan Van Riebeeck’s flotilla sailed into Table Bay and his orders from the Council of Seventeen were to build a fort, a hospital and provide water, meat and fresh vegetables to the passing ships. His assignment was not to colonise by means of settlement (as the English were doing on the eastern seaboard of North America) but to stay within an enclave, comprising the fort and its gardens, which would be in time surrounded by an almond hedge. He was also instructed to be on good terms with the indigenous people – the Khoikhoi for the purpose of bartering for beef and mutton. Interestingly Van Riebeck’s wife, Maria de la Quellerie was a Huguenot and thus was the first to set foot on Cape soil. She and her husband however would only stay for ten years before he gained promotion to Batavia, Java.

Painting of Table Bay (Illustrated History of South Africa - The Real Story)

This status quo could not endure and within five years it was realised that expansion beyond the almond hedge was necessary and therefore servants of the Company were released to become “Free Burgers” in order to farm the land used by the Khoikhoi as pasture. Thereafter a series of events occurred which brought about warfare between the Dutch and the Khoikhoi. The same story was repeated across the globe whenever European settlers came into conflict with the indigenous people in competition for the land and invariably it was the Europeans that won, with very few exceptions, owing to their superior weaponry.

Thus was set in motion the colonisation of the Cape which was to become “de facto” when in 1679 Simon van der Stel became Commander of the Cape. On his arrival the settlement was nothing more than a castle and trading post at the base of Table Mountain, yet to be called Kaap Stad (Cape Town). It was he who ventured out to establish the second settlement, which was to be named after him – Stellenbosch. By 1685 the Company tried to enlist Dutch farmers to increase the number of Free Burgers at the Cape by advertising free passage for “industrious families”, but those who came forward fell well below the quota needed. Thus it transpired in 1687 that Van der Stel was informed that the Company was sending numbers of Huguenots who had taken refuge in the Netherlands. Although they were destitute having left all their worldly goods behind in France the Huguenots were skilled and resourceful people and were just what the Cape needed to prosper.

The first ship bearing the Huguenots was the “Voorschooten” which left the Netherlands on 31st December 1687 soon to be followed by six others in the next few months and it would not be until the year 1700 that the last of the refugees was to arrive at the Cape.

The voyage to the Cape was long and could take anything from four to six months. Passengers shared the rigours of the sea voyage with the crew in weathering storms, surviving epidemics and experiencing shortages of fresh water and food. Hardship from illness and starvation was especially bad for those in ships that were forced to go around the north of Scotland in order to avoid French “Men of War” and many died at sea.

When newly arrived at the Cape, the Huguenots were taken to their allocated farms of 60 morgen (120 acres) in the Drakenstein district from Olifanthoek to Wagonmakers’ Valley (now Wellington), and were given farming implements and tools to build their homes. All was to be on credit until such time that the new settlers were on their feet and the debt could be repaid. Olifantshoek was first dubbed Le Coin Francais (French Corner) by the Huguenots which in Dutch was Fransche Hoek. An alternative name was La Petite Rochelle, so named after their major centre in France – La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast between Nantes and Bordeaux. This name did not last and with the assimilation of the Huguenots into the broader Cape Dutch community Franschhoek is what we know it by today.

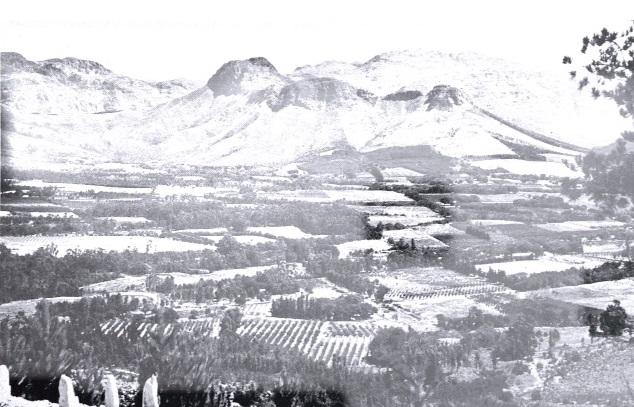

Franschoek Valley (History of South Africa)

Although it was hoped by many Huguenots that a separate community could be established where they could preserve their own language and culture, in reality it was a vain hope as the last thing the Dutch Administration wanted was a pocket of Frenchmen in their midst whilst at War with France.

In the 18th century (1701 and 1800) the Huguenots and Dutch intermarried and only the French surnames of Du Toit. Du Plessis, De Villiers, Le Roux, Malan, Marais, et al remained. In fact the Huguenot refugees that settled in London in Soho and Spitalfields were able to keep their customs for longer before assimilating and becoming English. Famous names of celebrities such as Lawrence Olivier, Daphne du Maurier, Reginald Bosanquet and Nigel Farage, have surnames that allude to their French Protestant ancestry.

Several members of the Springbok squad that toured France in 1968 had Huguenot surnames (Springbok Saga)

Although only 0.1% of Huguenot refugees came to the Cape they formed a sixth of its population in 1700 and were of great benefit to the fledgling colony, especially when it came to the cultivation of the vine and the beginnings of the successful South African wine making industry can be traced back to the vintners who came as refugees from France. By 1790 Constantia wines were on the tables of the rich and famous of Europe.

Huguenots wherever they settled made a difference and one can only hope that the refugees of today can emulate them given the opportunity.

Huguenot Monument (The Heritage Portal)

References and Further Reading:

- “Huguenot Society of South Africa” web site: www.hugenoot.org.za

- “The Huguenot Heritage” by Lynne Bryer & Francois Theron.

- “Illustrated History of South Africa – The Real Story” published by the Readers Digest.

- “History of South Africa” by W.J. de Kock.

- “Agriculture in South Africa” fourth edition.

- “Refugee Week: The Huguenots count among the most successful of Britain’s immigrants” from the “Independent” newspaper , 18 June 2015

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.