Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

"An ancient song, as old as the ashes, Echoed as Mageba’s warriors marched away." South African Contemporary Folk Song. Johnny Clegg and Savuka.

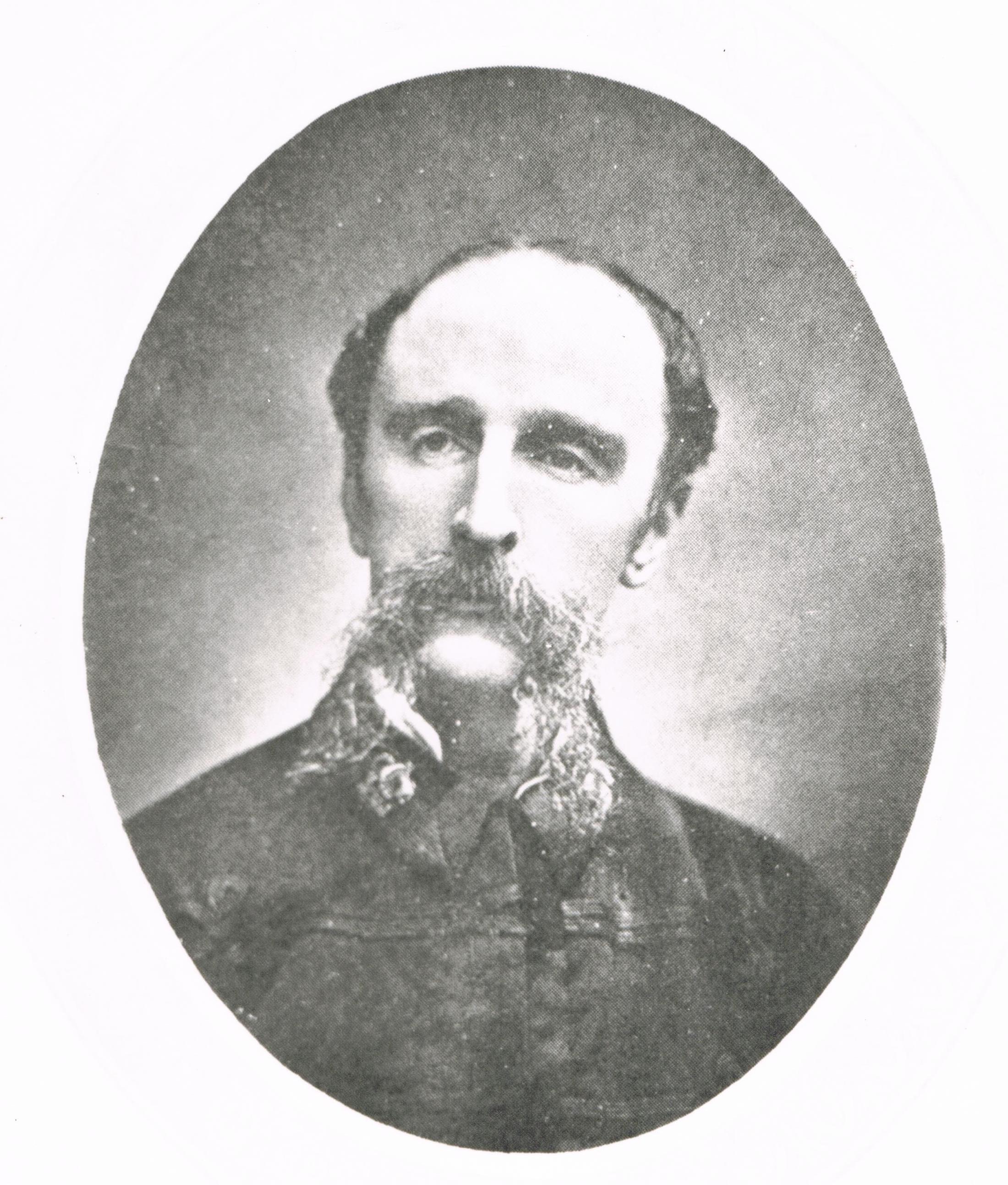

Colonel Anthony Durnford is probably the most enigmatic, controversial and colourful character associated with the British defeat at Isandlwana. Incontrovertibly the senior officer present, history has blamed him for the disaster for failing to exercise effective command and control.

Durnford

We are reasonably certain that Durnford left the camp before midday and took out a patrol of his own Natal Native Horse (NNH) around noon eastwards to just past the Conical Hill towards Qwabe, ostensibly to protect Chelmsford’s rear from any possible Zulu activity already reported from the Nyoni heights, but in effect breaking a cardinal rule – never, ever, split one’s forces in enemy territory. Possibly he wasn’t worried – after all, his Boss had already done that twice by going off on a wild goose chase down to the Mangeni.

The Zulus did indeed find him – the whole left horn of the Zulu army, to be precise. With just over 100 men, there was no hope in a stand-up fight but, if they retired systematically, dismounting at intervals to fire at the approaching horde, they could certainly slow them down.

According to a survivor’s account, Durnford was in his element. All his pent up frustration of having missed out of the action throughout his career was suddenly gone. This was what he was born for, and he rode back and forth, encouraging his men, shouting, laughing, holding the reins in his teeth (he only had one functional arm and kept his incapacitated one tucked in his tunic front) while discharging shots with his revolver towards the dense mass of warriors. Every time the Basutho Horse whirled away in a body, the Zulus lost ground behind them but caught it up every time the horsemen had to slow down to negotiate a tricky bit of boulder covered ground or a deep ravine.

They emerged out of the valley with the Conical Hill to their right (or north), heads down, going like the clappers with their horse’s chests heaving. As they did so, they saw the remnants of the Rocket Battery’s crew streaming away from their blood soaked position among the rocks at the base of iThusi to join them, some of the detached red coated infantrymen awkwardly hanging onto their commandeered horses for dear life.

Russell’s battery had moved out of camp with Durnford, but had taken a different course along the foothills of the Nyoni range until they had advanced some 3-4 miles to the east. This was observed by 1173 Private J. Bickley, who, watching the small force from the camp, said that “at this time we could see, with field glasses, Kaffirs on the hills to the left quite distinctly”. The battery was alerted by some Natal Carbineers who had been on piquet duty on the heights above. They clattered down the steep, boulder-strewn hillside, horses slipping and sliding on their hindquarters as they struggled for a foothold. Their report, “If you want any fun, come up to the top of the hill. They are thick up there” is probably one of the better understatements of the century.

Russell turned his small command towards the saddle between iThusi and the Nyoni. The column came to a halt, but they had barely unloaded the mules, when, as Lt. Temple Mayward Cracroft Nourse later explained, a force of Zulus “lying in the tall grass about a hundred paces off, and with that buzzing “Usuthu” of theirs, were on to us. It electrified the donkeys, which he-hawed down the hill with the speed of racehorses, in spite of their packs. My men disappeared as if by magic”.

They managed to fire just two rockets, which fizzed uselessly over the heads of the advancing Zulus to explode in the rocks beyond, before the Zulus were on them.

It isn't clear how Major Russell met his end. Private Grant later said that the enemy had fired their first volley, killing Captain Russell and 5 men - “Major Russell met his death, sword in hand, at the head of his little force”. However, 299 Private D. Johnson 1/24th says that he had tried to help Captain Russell off the field but that “he was shot before we had got many paces”.

Nourse says that he and Major Russell reached the foot of the hill together. “We halted to survey the scene … an unlucky shot struck Major Russell in the thigh, causing him to drop from his horse”.

Grant, Johnson and Trainer grabbed the battery horses and bomb-shelled away across the plain. Grant made it back to camp, where he later met Johnson and Trainer who had joined Durnford’s retreating force and had “come in with some Basuthos”.

Once again according to Nourse, he himself fled across the valley until he met up with Durnford’s retiring horsemen. “I told him the fate of the battery, and of Major Russell. The Colonel appeared very distressed and (muttered something) about not surviving such a disgrace”.

It is at this time that Durnford appears to have made the decision that not only robbed him of his chance to escape, but which ultimately killed him. It is difficult to justify his next move, which was to take a route around the southern slope of the Conical Hill towards the Nyogane river, which runs north-south about two miles away across the front of Isandlwana, and take up a defensive position there. According to Nourse, it was to “help delay the camp being completely surrounded”.

So far, so good. Based on Nourse’s evidence plus that of surviving NNH men, It has become common cause that the fight in the Nyogane river valley, the so-called Durnford’s Donga, took place.

The men tumbled into the donga, splashing through the water and then leapt out of the saddle while horse holders were detailed off. They threw themselves down on the eastern bank of the gulley, seeking cover in the mud and stones that lined it. Frantic hands fumbled at their cartridge belts and rounds were rammed into already smoking breeches.

And abruptly that fast roar of approaching Zulus, like combers breaking onto the beach. The whole earth starts to shake. “Crash, crash, crash” as a thousand spear butts slam into the rawhide shields. A high pitched squeal from a thousand throats. And there they come, looming out of the dust and getting bigger and bigger every second. Time stands still. The men could clearly see the contorted faces of the enemy, chests heaving, sweat flying off their bodies, ox tail tshobas blowing in the wind.

The command “Fire!” would have been followed by the disciplined crash of 70-odd rifles. “Reload!”

According to all accounts, the two troops of Natal Native Horse involved made a very gallant stand, picking off members of the inGobamakhosi and uMbonambi amabutho almost at will. Durnford was prominent, once again displaying outstanding personal qualities of courage and fortitude that are difficult not to acknowledge.

Private E. Wilson 1/24th stated that “to the right front some of the Police, Carbineer and Native Levies were engaged very hotly and retiring on the camp. They made a stand for some time in a sluit which crossed in front of the camp, but were driven out of it after half an hour”.

But taking up a position in a donga merely robs one of the ability to appreciate the whole picture. With restricted visibility and up to one’s eyeballs in crocodiles, it is impossible to make rational decisions that affect thousands of men. The defence of the Nyogane donga, however heroic, was a Sergeant’s command, not a Colonel’s. With hindsight, Durnford should have made his way back immediately to camp, assumed command from Colonel Pulleine and done what he could to bring the situation under control. Or else, even at that stage, Durnford was unaware of the enormity of the approaching foe and decided to have a bit of “fun” while he could before the natives inevitably fled.

There is no evidence that he ever did so.

The next few minutes are unclear. It is widely assumed that diminishing ammunition supplies forced Durnford’s command to evacuate their position, thereby exposing “G” Company’s right flank beside them. Lieutenant Pope on Durnford’s left would have had no choice but to conform to his Colonel’s movements and also retire, thus exposing Wardell’s flank, and so on. The result was a collapse of the line and a precipitate retirement towards the high ground at the rear.

But the first question to be asked is – did Durnford ever leave the donga to retire up towards the nek, or did he die there?

The first clue comes from Mackinnon and Shadbolt. According to them, Lieutenant Francis MacDowel R.E. “was seen fighting side by side with Col. Durnford in the desperate charges that Officer was making to repel the encircling Zulu forces”.

The authors later stated that MacDowel, when last seen, was “getting bandsmen, gunners and others together and bringing up reserve ammunition to the fighting line of the 24th. Regiment. A Zulu fired at him, and he fell between the General’s tent and the firing line” The question would be, then, just which ammunition wagons – the 1st Battalion at the foot of the Stony Kopje or the 2nd Battalion’s wagons half way along Isandlwana itself? The General’s tent was in the middle of the position, so, presumably, the 2nd battalion’s wagons.

So, if MacDowel was still with Durnford at this stage, this would suggest that Durnford did indeed retire. But where was he? That question remains unanswered.

There is no evidence that MacDowel and Durnford died together. However, if they did, and if Mackinnon and Shadbolt are correct, that would probably place them in the middle of the British camp near the 2nd Battalion’s ammunition wagon.

We do know that the remnants of Durnford’s command, some 15 men under Lt. Henderson, sent from the donga to collect spare ammunition some half an hour previously, disappeared and eventually turned up almost intact at Rorke’s Drift Mission Station later that afternoon. Lt. Harry Davies and the Edendale contingent also escaped. His Principal Staff Officer, Captain George Shepstone, took Captain Edward Erskine’s amaCunu company of the N.N.C. in an attempt to break out towards Rorke’s Drift but was swamped by the Nonkenke ibutho racing around the backward slopes of Isandlwana itself. His grave can be found there.

So we can be reasonably sure that at least some of Durnford’s command managed to escape from the donga but that it disintegrated soon afterwards.

The fighting around the nek was chaotic, to say the least. In the camp area the tents were being torn down by wild-eyed Zulus, hunting for loot, firearms and alcohol. Their former red jacketed occupants lay strewn all around, struck down and thrown aside to be butchered for souvenirs later.

Small stands were taking place everywhere, with Zulus charging with fanatical courage into bristling rows of bayonets, throwing the bodies of their dead comrades onto them to drag the weapons down. As soon as a gap opened up, the Zulus were in, flailing away with their broad bladed spears, hacking and stabbing for all they were worth. Equally desperately, the British fought back with anything to hand, their ammunition expended.

A mass of stumbling, panic-stricken refugees were pouring over the saddle between Isandlwana and Mahlabamkosi or the Stony Kopjie in a futile attempt to flee the carnage. According to Davies:

I saw a great many wagon drivers, leaders and many others leaving the camp … making direct for the river. I saw … Zulus pouring down in great numbers at the back of Isandlwana hill thereby cutting off our retreat.

Surgeon Major Peter Shepherd’s hospital had been overrun, the patients skewered as they lay on the ground. Some of them were run over by the thundering hooves and wheels of one of the N5 Battery 7 pounder guns, the axle tree and limber covered with fugitives like ticks on a dog’s back, careering out of control through the tents.

Slightly above Shepstone, on the little knoll half way up Isandlwana, a company of red coats was fighting it out to the last, standing back to back and resorting to knives, sticks and rocks as their ammunition finally ran out.

The din was indescribable, and the area resembled a slaughterhouse:

… the green grass was red with the running blood and the veld was slippery, for it was covered with the brains and entrails of the slain. The bodies of black and white were lying mixed up together with the carcasses of horses, oxen and mules.

And then catastrophe! The Zulu right horn finally made it around the back of Isandlwana, driving the British draft and slaughter oxen in a panic stricken mob before them. According to Nourse’s later testimony:

Good God! What a sight it was. By the road that runs between the hill and the kopje came a huge mob of maddened cattle, followed by a huge swarm of Zulus.

The whole mass scythed through the remains of the wagon-park and isolated groups of frenzied, hacking, stabbing, and shooting men like a tidal wave. Those that were quick enough managed to reach higher ground and get out of the way, but the greater mass of men were swept away in the chaotic maelstrom.

Once the force of the stampede had spent itself, only a handful of soldiers still stood amidst a sea of Zulu warriors. It is therefore very difficult to trace the movements of individuals, or even bodies of men for that matter, in those last desperate, frantic moments.

So, whatever happened to Durnford?

Aftermath

The first real attempt to return to the site of the disaster at Isandlwana in order to bury the dead and recover as many wagons as possible only took place on 21st. May 1879. It was undertaken by members of the newly formed Cavalry Brigade under General Frederick Marshall.

According to Colonel Black:

...the bodies of the slain lay thickest on the 1/24th. camp, a determined stand had evidently been made behind the officer’s tents …. seventy dead lay there. Lower down the hill in the same camp another clump of about sixty lay together, among them Captain Wardell, Lieutenant Dyer, and a captain and subaltern of the 24th. unrecognisable. Near at hand were found the bodies of Colonel Durnford, Lieutenant Scott and other Carbineers, and men of the Natal Mounted Police, showing that here also our men had gathered and fought as a recognised body. This was evidently a centre of resistance as the bodies of men of all arms were found converging as it were to the spot, but stricken down ere they could join the ranks of their comrades. About sixty bodies lay on the rugged slope, under the southern precipice of Isandlwana, among them those of Captain Younghusband, and two other officers, unrecognisable; it looked as if they had held the crags, and fought together as long as the ammunition lasted.

According to Colonel Black, then, Durnford’s body was found “lower down the hill in the 1/24th camp”.

Ian Knight almost concurs. According to him, Durnford’s body was found:

lying in the long grass just below the 1/24th. camp, the long moustache still clinging to the withered skin of his face. Round Durnford lay a cluster of Volunteers, Mounted Police and a few men of the 24th. Trooper Swift (Natal Carbineers) … had died hard: they killed him with knobkerries. Mackleroy was shot through the side … he managed to get on his horse and ride half a mile when he fell, and nothing more was seen of him. Lieutenant Scott was hidden partially under a broken piece of wagon, evidently unmutilated and untouched. He had his patrol jacket buttoned across, and while the body was almost a skeleton, the face was still preserved and life-like, all the hair remaining, and the skin strangely parched and dried up, though still perfect.

The difference between the two accounts is that Durnford’s body was either found in the camp or just below the camp.

However, the work of burying the dead could not be done very thoroughly due to the rocky nature of the ground. In “The Sun Turned Black”, Ian Knight says that Durnford’s body was wrapped in a tarpaulin, and buried under the side of a donga.

Two authorities therefore agree that Durnford not only got out of the donga but managed to make it to the 1/24th camp lower down (i.e. east) the hill when he died, surrounded by a little force of loyal companions.

Once again, though, things are not as simple as they seem. One of the Lloyd photographs taken in May 1879, published in Donald Morris’ “Washing of the Spears” and captioned as the site of Durnford’s last stand, was taken from a point on the Fugitive’s Trail i.e. to the west of the mountain, not to the east as indicated by Colonel Black. One only has to look at the profile of the mountain to see that its sphinx shape has all but disappeared and the most one can see is the “head”.

See also William Whitelocke Lloyd’s “A Soldier-Artist in Zululand” which depicts Melton Prior’s pen and ink sketch made on 21 May 1879. The perspective of this sketch, too, is taken further down the Fugitive’s Trail and shows exactly the same profile as Lloyd’s photograph. Melton Prior wrote -

the individuals could only be recognised by such things as a patched boot, a ring on the finger bone, a particular button, or coloured shirt, or pair of socks in a few known instances … the hands of the enemy, or the beaks and claws of vultures tearing up the corpses, had in numberless cases so mixed up the bones of the dead that the skull of one man, or bones of a leg or arm, now lay with parts of the skeleton of another.

Two questions, then. Firstly, who is correct, Colonel Black (and Ian Knight is obviously basing his conclusions on that evidence) or Lloyd and Melton Prior? Did Durnford die to the east (in the 1/24th camp) or west of Isandlwana (on the Fugitive’s Trail)?

Secondly, how on earth could anyone positively identify individual bodies almost four months after the battle? Hacked to pieces, mutilated, decomposed, eaten by numberless scavengers, picked over by the Zulus, uniforms rotted, only personal items such as rings, medallions, pen-knives, monocles and cigarette cases would assist to make a tentative identification. Other items of brass and copper, such as buttons and badges, would also have survived. But the remainder … no!

There is a story that Durnford was identified by his famous moustache, but that is highly unlikely considering that the Zulus regarded a moustache as one of their most desirable trophies. No doubt especial efforts were made to try and find Durnford’s body, since he was the senior officer present, but I have a sneaking suspicion that it was more likely that the story was embellished to keep his lady love, Frances Colenso, a fierce critic of British ineptitude, quiet and give her closure and something to bury.

According to R.W.F. Drooglever –

In October 1879 the Colenso’s decided to have Durnford’s body brought from Isandlwana and buried in the military cemetery at Fort Napier (Pietermaritzburg). The Natal Colonist recorded the occasion:

The sky (on Sunday) afternoon (12 October) was dark and threatening, and there appeared every prospect of a heavy thunderstorm. Still, even this did not deter almost every inhabitant of Maritzburg from attending to show their last tribute to a gallant leader …

At 4 p.m. the coffin, covered with the Union Jack and flowers and containing the remains, was placed on a Royal Artillery gun carriage and the procession slowly moved off to the cemetery … the band of the 99th. playing the “Dead March of Saul”.

Practically every Regiment in Natal, both Imperial and Colonial, was represented. Soldiers numbering over 2000 followed the cortege. 300 men of the 24th. Foot composed the firing party.

The Reverend G. St. M. Ritchie, military chaplain, praised Durnford in the following manner at the graveside:

A brave and devoted soldier, a generous attached friend, he possessed almost every faculty which is calculated to make one man the leader of his fellow men and this he emphatically was … we shall never look upon his like again.

The last question, then, is do the remains in that coffin even belong to Durnford?

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

References

- “Casualty Roll for the Zulu and Basuto Wars. South Africa 1877–79” by I.T. Tavender. J.B. Hayward and Son. Polstead, Suffolk 1985.

- “England’s Sons”. Julian Whybra. Gift Limited, Billericay, Essex. March 2004.

- Knight, Ian. Just about anything that he’s ever written.

- “Medal Roll for the South African War 1877-8-9”. Compiled by D.R. Forsyth.

- “Narrative of Field Operations Connected with the Zulu War”. Prepared by the Intelligence Branch of the War Office. Greenhill Books, London. 1989.

- “The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879” by G.A. Chadwick. Appeared in the SA Military History Society’s Journal Vol. 4 No. 4.

- “The Road to Isandlwana”. R.W.F. Droogleever. Greenhill Books, London. 1992

- “The Silver Wreath” by Norman Holme. Samson Books, London. 1979.

- “The South African Campaign of 1879”. J.P. MacKinnon and S. H. Shadbolt. Greenhill Books, London. 1995

- “They Fell Like Stones”. John Young. Greenhill Books, London. 1991.

- “Zulu Battle Piece – Isandlwana”. Sir Reginald Coupland.. Tom Donovan Publishing, London. 1991.

- “Zulu War Then and Now”. Ian Knight and Ian Castle. Battle of Britain Prints, London. 1993.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.