Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Remembrance tourism is all about visiting battlefields, fortifications, war cemeteries, memorials, etc., and is fast becoming a popular pastime.

During the last few years, Lorraine and I engaged in this type of tourism by viewing some Anglo Boer War sites and memorials at Colesberg, Noupoort, Middelburg, Aberdeen, Nieu Bethesda, Willowmore and Uniondale.

We omitted Graaff-Reinet because to view its historical sites would have added considerably to an already hectic travelling schedule.

Colesberg, Aliwal North, Burgersdorp and Stormberg were about as far south-east as the Boer forces advanced during their 1st invasion of the Cape Colony, upon the outbreak of war. During this buoyant early period, possibly misled by Republican hubris that the war would soon be over, 10 000 Cape Rebels enthusiastically joined up. But despite victories at Colesberg and Stormberg, by early 1900 the Republican forces were retreating across the Orange River to try and stem the advance of the powerful Imperial army along the railway line to Kimberley and from there to Bloemfontein. Abandoned by the retreating Boer commandos, many Cape Rebels quietly returned to their farms.

From October 1900, captured Cape Colonial Rebels were charged under the Special Tribunal’s Act. Rebels sentenced by these Special Courts were treated so leniently that it bordered on amnesty. Unfortunately, these lenient sentences encouraged rather than prevented Cape Rebels from joining the fray once the war proved far from over.

To the British, the war appeared to be won once they had captured Bloemfontein and Pretoria. So much so, that following the victory at Dalmanutha, near Belfast in August 1900, Field Marshall Roberts triumphantly telegraphed the British government that the war was over.

Even to the Boers the powerful Imperial forces seemed unstoppable. But at that critical time, in early June 1900, General Christiaan De Wet captured a convoy of 56 Supply wagons at Zwavelskrans and three days later launched simultaneous attacks on a large consignment of stores at Rooiwal (Roodewal) station and on a military construction camp at the nearby Rhenoster River. With these surprise attacks De Wet showed that the formidable but thinly stretched Imperial forces were vulnerable to guerilla attacks. Suddenly, hope arose that a successful guerilla campaign would bring about a reasonable peace settlement.

But as the relentless British Scorched Earth policy continued with the destruction of farms and forcing Boer and African women and children into ill-prepared concentration camps, President Steyn advocated a new invasion of the Cape Colony. This would relieve the pressure on the Boer Republics, disrupt the enemy’s supply lines and recruit new Cape Rebels.

On 15 December 1900, Generals Barry Hertzog and Pieter Kritzinger, shortly followed by other Boer commandos, crossed the Orange River to put this plan into practice.

But by April 1901, the situation for Cape Rebels had changed dramatically. The military had taken over the courts, and Martial Law been declared over virtually the whole of the Cape. Captured rebels now faced trial by Military Courts that handed down harsh sentences, including execution, to those found guilty of charges, such as, ‘high treason, active in arms, house burning, barbarous acts contrary to the customs of war, and attempted homicide’. This meant that after April 1901, a youngster who had lightheartedly rebelled when punishment was minimal, suddenly found he could now be sentenced to death if captured.

The military labelled Cape Rebels in positions of authority as ‘persons of standing’, and when captured, they were almost invariably executed. Therefore, while most Cape Afrikaners sympathised with their kith and kin in the embattled Republics, less than 3 000 rebels joined this 2nd Boer invasion.

The Jingoist press called the Cape Rebels poor and backward. The editor of the Midland News said that ‘those who have joined the enemy are for the most part not the more well to do, or the most respectful part of the Dutch population’. These statements are broadly speaking correct, but certainly some respectable Cape Afrikaners also rebelled.

Captured Cape Rebels were executed in many of the Cape districts. To intimidate the local Afrikaner population, General John French, Officer Commanding the Cape Midlands, ordered that all executions should take place in public. Locals suspected of being rebel sympathisers and branded as ‘undesirables’, were forced to attend these executions.

44 Cape colonists, Republicans and aliens were executed, and hundreds of others, whose death sentences were commuted to penal servitude for life, were shipped to POW camps on the Bermuda and St Helena islands.

While we saw numerous memorials to fallen Imperial soldiers and Boer burghers as well as Cape Rebels, the omission of any memorials to African and Coloured scouts used by the British military or as ‘agterryers’ by the Republican commandos, was very notable. The Boer commandos often thrashed or shot these scouts out of hand, and it would be appropriate to recognise their participation in this war, that was not only limited to the Boers and British.

1. Colesberg

Founded in 1830 on an abandoned station of the London Missionary Society and initially named Tooverberg after a nearby hill, it was renamed Colesberg after Sir Lowry Cole, erstwhile Governor of the Cape Colony.

The Military Garden of Remembrance is situated at the southern end of Colesberg on the western side of Station Road. The three memorials record the names of 282 Imperial soldiers, of whom 141 were killed in action or died from their wounds. Many of these casualties, date from battles and skirmishes to control Colesberg during the 1st Boer invasion, such as at Suffolk hill, Arundel station and Jasfontein farm, etc.

The Imperial Garden of Remembrance at Colesberg (SJ de Klerk)

Adjacent to this Garden of Remembrance is the Burgher Memorial commemorating the 46 burghers who fell at Colesberg. It also commemorates five Cape Rebels executed here by firing squad, during the 2nd Boer invasion of the Cape.

Two of these rebels, Hendrik Veenstra and Frederick Toy were part of a group of Gideon Scheepers’ Commando captured in July 1900, at Onbedacht, in the Camdeboo mountains, between Graaff-Reinet and Murraysburg. This was a severe blow to Scheepers, not only did he lose several of his men, but suddenly the hitherto safe Camdeboo had become too dangerous. He and his men fled it, never to return. Hendrik (Jan) van Vuuren managed to escape from Onbedacht but was captured a few days later.

Veenstra, Toy and Van Vuuren were tried in Graaff-Reinet and found guilty of high treason, being actively involved in arms, and/or murder and sentenced to death. All three were shot by firing squad on 4 September 1901, on the outskirts of Colesberg, near the road to Hanover.

The other two Cape Rebels on this memorial, Willie Louw and Nicholaas van Wijk (Wyk), were captured near Philipstown, north-east of De Aar.

Louw and Van Wijk were sentenced to death in Graaff-Reinet and Middelburg, respectively, and executed in Colesberg during November 1901.

The location of these five graves, other than the one of Louw, is now lost. Louw, related to the well-known ecclesiastical Murray family, was later reinterred on the family farm ‘Eenzaamheid’, in the Colesberg district.

Memorial to Boers killed at Colesberg. Note the names of 5 Cape Rebels ‘Door den vyand veroordeeld en geschoten’ (Sentenced and shot by the enemy) (SJ de Klerk)

2. Noupoort

Our next stop was Noupoort, (previously Naauwpoort) meaning narrow gorge and named after a gap in the Carlton Hills, some 27 km south of this village.

This important railway junction of the East London/Bloemfontein line with the one to De Aar was garrisoned during the war and No. 26 General Hospital also stationed here. Guerilla leaders, Gideon Scheepers and Pieter Kritzinger were both treated here following their respective captures.

Anglo Boer War blockhouse at Noupoort (SJ de Klerk)

We visited the unusually shaped blockhouse on Hospital Hill and the nearby Military Garden of Remembrance. This blockhouse has been described as one of the most idiosyncratic buildings of its type in South Africa. Circularly shaped, the whitewashed stone tower is 7 m high and resembles a tower windmill such as Mostert's Mill in Cape Town.

The Garden of Remembrance contains the remains of 272 Imperial soldiers, of whom five were killed in action or died from their wounds. About 250 names appear on a combined memorial to these soldiers. There are also 22 individual graves of soldiers.

Imperial Garden of Remembrance at Noupoort (SJ de Klerk)

For those interested in other sites in Noupoort, All Souls Anglican church in Shaw Street, was designed by WJA Rose, a railway engineer, to commemorate the fallen soldiers. Soldiers who were also skilled stonemasons commenced building the church in 1901. Since the soldiers were repatriated before completion, the apse was completed with red face brick. The town museum is now curated here, but we did not visit it.

3. Middelburg

Middelburg, our overnight stop, was laid out in 1852, and so named because it is equidistant from Cradock, Colesberg, Steynsburg and Richmond.

We were sorry that time constraints did not allow us time to visit the nearby Grootfontein Agricultural College. This site was used as a cantonment by the British garrison after the Boer War, until 1908. Upon repatriation of the garrison the grounds and buildings were purchased by the Cape Colonial government and used for the establishment of this college.

We were now in the Cape Midlands, where Commandants Hans Lötter, Gideon Scheepers, Willem Fouché and General Pieter Kritzinger were very active during the guerilla war.

Middelburg was an important garrison town, as it was from here that General French directed efforts to defeat and capture the guerilla commandos.

With sunset fast approaching, there was just enough time for a quick visit to the old town cemetery in Van Reenen Street. The remains of 40 Imperial soldiers were interred here, of whom 6 died of their wounds. It appears that this cemetery closed in about 1903/04 and that a new cemetery was then established in Station Street, near the railway station.

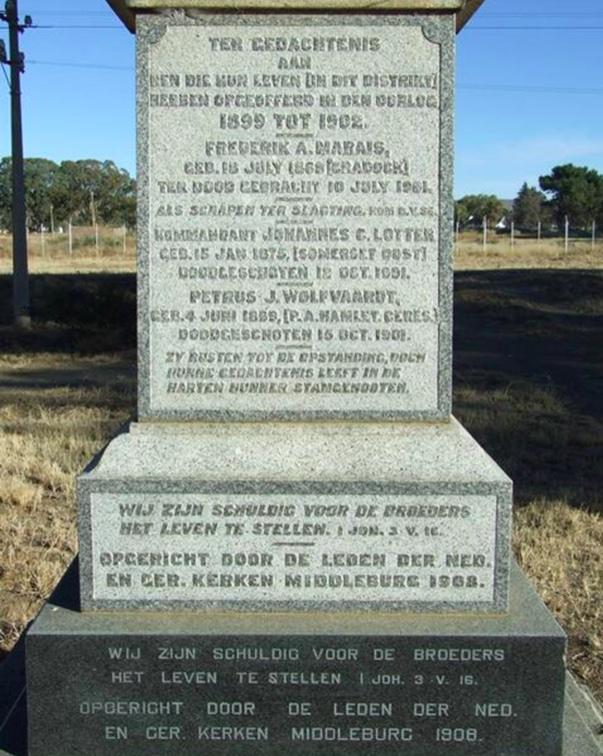

The following morning, a short drive took us to the so-called ‘Stoel Monument’ (Chair Monument) at Ouberg hill, on the road to Richmond. This monument marks the spot where Commandant Johannes (Hans) Lötter and his adjutant Pieter Wolfaardt were shot by firing squad on 12 and 15 October 1901, respectively (see main image).

The engraved chair symbolizes how many Cape Rebels met their end – tied to a chair next to an open grave before execution by firing squad.

Lötter ran a bar at Noupoort prior to the war but during the 1st invasion he joined the Boer forces at Colesberg. Later, with his own commando they roved around the Cape Midlands, ambushing smaller Imperial units and destroying railway infrastructure. After a skirmish near Cradock, they retreated to the hamlet of Petersburg east of Graaff-Reinet in the foothills of the Bankberg. The cold and rainy night of 4 September 1901 found them sheltering in a shed and kraal at nearby Bouwershoek. Considering themselves safe from surprise attack in this mountainous area, they failed to place sufficient lookouts on duty. But Lieutenant-Colonel Harry Scobell, the famed guerilla hunter, was already on their trail. After feinting north, he and his men completed a rapid night march to attack the Boers from the direction least expected, the north. The Times History of the War recorded, ‘The surprise was absolute; but Lötter and his men were campaigning with ropes around their necks, and for a while fought desperately.’ With 13 men killed and 43 wounded, surrender became the only option. Five Cape Rebels were court martialed in Graaff-Reinet, including Lötter and Wolfaardt, but executed in various Karoo towns while the remaining 110 were exiled to POW camps in Bermuda. The British lost 9 men killed.

Pieter Wolfaardt, a Cape Rebel, also captured with Lötter’s commando, was executed because he had kept on firing after some Boers had raised a white flag.

Frederik Marais, however, was captured with another group of 10 burghers during a night attack on General Pieter Kritzinger’s commando, between Aliwal North and Lady Grey, also by the redoubtable Lieutenant-Colonel Scobell, in the winter of 1901. Sentenced to death at Dordrecht, Marais was hanged at the Middelburg prison during July 1901.

Our last visit before leaving town was to the newer cemetery in Station Street, to visit the communal grave where the remains of Marais, Lotter and Wolfaardt were reinterred in 1907. Members of the Middelburg Dutch Reformed and Reformed (Dopper) churches, erected a memorial in 1908 over this grave.

Memorial erected in 1908 by members of the Dutch Reformed and Reformed churches in Middelburg over the communal grave of executed Cape Rebels F Marais, J Lötter and PJ Wolfaardt (SJ de Klerk)

4. Nieu Bethesda

Nieu Bethesda is a picturesque Eastern Cape village where ‘leivore’ (water furrows) still line the gravel streets. Here, the late outsider artist Helen Martins, created nativity displays and other ornaments made from materials readily at hand, such as recycled glass bottles, cement, mirrors and wire in her house and garden, now known as The Owl House. During her lifetime she transformed this house and garden into a symbolically intense world of wonder and mystical insights.

Founded in 1875 as a mission station, Nieu Bethesda attained municipal status in 1886. The name is of New Testament origin (John 5:2-40) and means ‘place of flowing water’.

There is only one military grave in the well-maintained historic cemetery. It is the marble grave of Sergeant Charles Stacey of (General) French’s Scouts killed in action on 10 August 1901. In a reference to this skirmish, The Times History of the War in South Africa reports that on this date, ‘Lötter snapped up a party of French’s Scouts near Bethesda Road’, which is situated quite close to Nieu Bethesda.

Tombstone of Sergeant Charles Stacey of French’s Scouts killed in action on 10 August 1901, near Nieu Bethesda. (SJ de Klerk)

5. Aberdeen

At the risk of repeating myself, Aberdeen, like so many other Karoo villages, is well worth visiting. The settlement was named after Aberdeen, Scotland, in honour of the birthplace of the Rev Andrew Murray (senior) and became a municipality in 1858.

It boasts an attractive Dutch Reformed Church complete with towering spire 50 m high, that dominates the central town square and indeed the whole village.

Aberdeen also has a well-preserved architectural heritage with a spectacular array of Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, Art Nouveau, Gothic Revival and Flemish Revival styles, interspersed with typical Karoo style cottages.

The cemetery provides a window on the Boer War in the Cape Midlands. The Military precinct contains the graves of 23 Imperial soldiers of whom 18 were killed in action or died from their wounds.

A few Boers, killed in the vicinity are also buried here including John (Jack) Baxter. Baxter served in the so-called Rijk Section (Dandy Section) with Deneys Reitz and a few others, in Smuts’ commando. When they overran a column of the 17th Lancers at Modderfontein in the Tarkastad district, some Boers (including Baxter) replaced their tattered clothing with looted British uniforms, not realising the wearing of such clothing was a capital offence.

Shortly thereafter, Baxter, while with Smuts’ commando, lost his way in the morning mist and was captured by troops of Colonel Scobell. Taken to an outspan known as Goewermentsvlei near Aberdeen, he was summary court martialled for wearing a British uniform and shot by firing squad, all on the same day of 13 October 1901.

Tombstone of John (Jack) Baxter of Jan Smuts’ Commando executed by firing squad on 13 October 1901 at ‘Goewerments-vlei Aberdeen, for the wearing of a British uniform.

Col Scobell recorded in his diary, ‘He was an extraordinary good plucky chap. Never even changed colour when I told him his sentence, just asked for paper and pencil and wrote letters all the time. I could not help shaking hands with him, telling him how sorry I was and how I admired his bravery. He said: I am all right. Don’t bother about me. We are both soldiers and have to die sooner or later.’

Baxter’s remains were reinterred in the Aberdeen cemetery in 1906 and a tombstone erected over his grave in 1938.

Another famous historical figure who saw action near Aberdeen that would have far reaching consequences, was the then Sub-Lieutenant Lawrence Edward Grace (Titus) Oates. Serving with the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, his left thigh was shattered on 6 March 1901, by a Boer bullet in a skirmish with some of Commandant Willem Fouché’s commando. When called upon to surrender he replied he had come to fight, not to surrender. After treatment, also at the military hospital in Noupoort, his left leg remained shorter than the other. In 1912, Oates was one of the four men that accompanied Captain Robert Scott in his famous attempt to be the first to reach the South Pole. His old war wound broke open on the exhausting return journey, and he also suffered from frostbite and gangrene. Realising that he was holding the others back on their desperate race to reach the One Ton food depot, he left their tent into a -40°C blizzard, on the morning of his 32nd birthday on 17 March 1912, with the immortal last words, ’I am just going outside and may be a while’.

6. Willowmore

On our first visit to Willowmore, we visited the old, but very well-maintained Jewish cemetery and abandoned Synagogue, a reminder of times past when flourishing Jewish communities were common throughout the Karoo. On subsequent visits we also came to appreciate the historic Anglican St Matthews Church, built to a design by Sophy Gray, wife of the first Bishop of the Cape Colony, and other fine buildings.

The town was laid out in 1862 on the farm Willow, owned by William Moore, and during its first years was known as either Willowmoore or Willowmore. Only from 1890 onwards did Willowmore gain universal acceptance.

Willowmore saw considerable action during the 2nd invasion of the Cape. It was attacked twice by Boer Commandos under the command of Commandant Gideon Scheepers on 19 January and 1 June 1901.

There are four graves from the war in the old section of the municipal cemetery.

The tombstones of Sergeants E Liddiard of the Imperial Yeomanry and R Anderson, Brabants’s Horse, both killed in action on 23 February 1901, at Toorwaterpoort, west of Willowmore.

The third tombstone of Corporal Ignatius Wilhelm Oosthuizen of the Willowmore District Mountain Troop is interesting. His epitaph, perhaps a reflection of those desperate times, reads, ‘Age 19, who was brutally murdered at Baviaan's Kloof in the division of Willowmore on the 18th May 1902 by colonial rebels and thieves who had deserted their commandoes.’

The fourth grave is the one of CP Marais, a member of Scheepers’ commando who died on 2 June 1901, from wounds received in the attack on the town the previous day.

7. Uniondale

Uniondale, where our self-styled remembrance tour concluded, was founded in 1865 by the union of two villages, Hopedale and Lyon.

Behind the historic All Saints Anglican church, built to the design of Sophy Gray, lies the old English Cemetery dating from 1876. In the centre of this cemetery is a memorial to 12 Imperial soldiers from the SA Light Horse, and 10th Hussars Regiments, as well as the Uniondale Mounted Troop, killed in the area and as distant as Oudtshoorn.

Memorial to Imperial soldiers killed in the Boer War at Uniondale and surrounding areas (SJ de Klerk)

The graves to the rear of the four-sided memorial that now appear as mere mounds of stone, may date from the Great Spanish Flu of 1918.

Lower down the cemetery, there are three graves to troopers A Collins and AH Jones of the Imperial Yeomanry killed on 19 and 31 January 1901, respectively, and A Brassington of the 10th Hussars killed on 19 August 1901.

On 19 August 1901, the 10th Hussars launched an attack on Commandant Scheepers’ commando of about 270 men in the Langkloof near Avontuur. When the Boers counter-attacked the Hussars panicked and fled. Three Hussars were killed, namely Sergeant-Major W Clarke, Troopers Brassington and W Saunders. Their names also appear on the above memorial.

From Uniondale, the adventurous traveler with an appropriate vehicle, may elect to proceed through the historic Uniondale Poort and adjoining Prince Alfred’s Pass to Knysna. Both were built by the Victorian era road and pass builder, Thomas Bain, responsible for many of the Cape’s beautiful old passes. You will be excused if your attention is only drawn to the spectacular scenery and Bain’s famous dry walling method of construction. But look out for the monument commemorating Gideon Scheepers’s activities in this region. On the western side of the R339 between Uniondale and Avontuur about 2.2 km north of the R62.

SJ de Klerk is a retired human resources practitioner. Since retirement he has been writing articles on various aspects of South African history for The Heritage Portal. He is Chair of the Northern Branch of the Archaeological Society.

Sources and Further Reading

- Amery L. S. (General Editor). The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899 – 1902. Vol 5. Sampson Low, Marston and Company, London. 1907.

- Beyers C. J. (Editor in Chief). Johannes Lötter in Dictionary of South African Biography. Vol 5.

- Conradie C. F. Murraysburg tydens die Anglo-Boere Oorlog. Not dated.

- De Jongh M. & Gordon B. The Forgotten Front. Watermark Press. 2018.

- Grobler J. Anglo Boer War. Historical Guide to Memorials and Sites in South Africa. 30°South Publishers, Pinetown. 2018.

- Hoevers J. Geskiedkundige Kerke. Kontak-uitgewers. 2012.

- Jooste G. & Webster G. Innocent Blood. Executions during the Anglo-Boer War. Spearhead, Cape Town. 2002.

- McNaughton A. When Ants get Angry. The importance of Graaff-Reinet during the Anglo-Boer War. Not dated.

- Oosthuizen A. V. Rebelle van die Stormberge. JP van der Walt, Pretoria. 1994.

- Raper P. E., Möller L. A. & Du Plessis L. T. Dictionary of South African Place Names. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Jeppestown. 2014.

- Reitz D. Commando. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg. 1990.

- Shearing T and D. Commandant Johannes Lotter and his rebels. Privately printed. 1998.

- Shearing T and D. Commandant Gideon Scheepers and the search for his grave. Privately printed 1999.

- Shearing T and D. General Jan Smuts and his long ride. Privately printed. 2000.

- Snyman J. H. Rebelle-Verhoor in Kaapland gedurende die Tweede-Vryheidsoorlog met spesiale verwysing na die Militêre Howe, 1899 – 1902. Archives Year Book for SA History. Cape & Transvaal Printers, Cape Town. 1963.

- Storrar P. A Colossus of Roads. Hansa Reproprint, Cape Town. 1984.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.