Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The value of the photographic postcard, a unique historical document in itself, has been vastly underestimated by historians. Today, these types of photographs are of immense value in both photographic as well as social historical research.

It was not until recently that the author himself started to incorporate these long-undervalued photographic formats, also commonly referred to as the Real Photo Postcard (RPPC), into his own photographic research collection.

The author conducts research on South African photographic history prior to 1915 and therefore had to consider including any South African Real Photo Postcard produced between around 1902 and 1915 into his research field to obtain a broader perspective around professional photographer activity during this period.

The first permanent photographic image was introduced in the Daguerreotype format (around the 1840's), followed by the Ambrotype, then the paper based versions of the Carte-de-Visite, Cabinet cards and stereo cards, with the tintype somewhere in between. The Real Photographic Postcard format was only introduced post these photographic formats around 1902 and remained popular until the 1930’s. RPPCs had significant advantages, the main one being that they were easier to produce than the photographic formats mentioned above. Local photographers quickly introduced this format as part of their service offerings.

A whole range of human experiences were photographically captured and produced on the RPPC. Although described as “all-time most popular photographic format” in the USA, the author is not convinced that this holds true in the South African context in that the number and variety of these type of photographs are sadly not as diverse or creative as compared to the photographs produced in this format in both Europe and the USA.

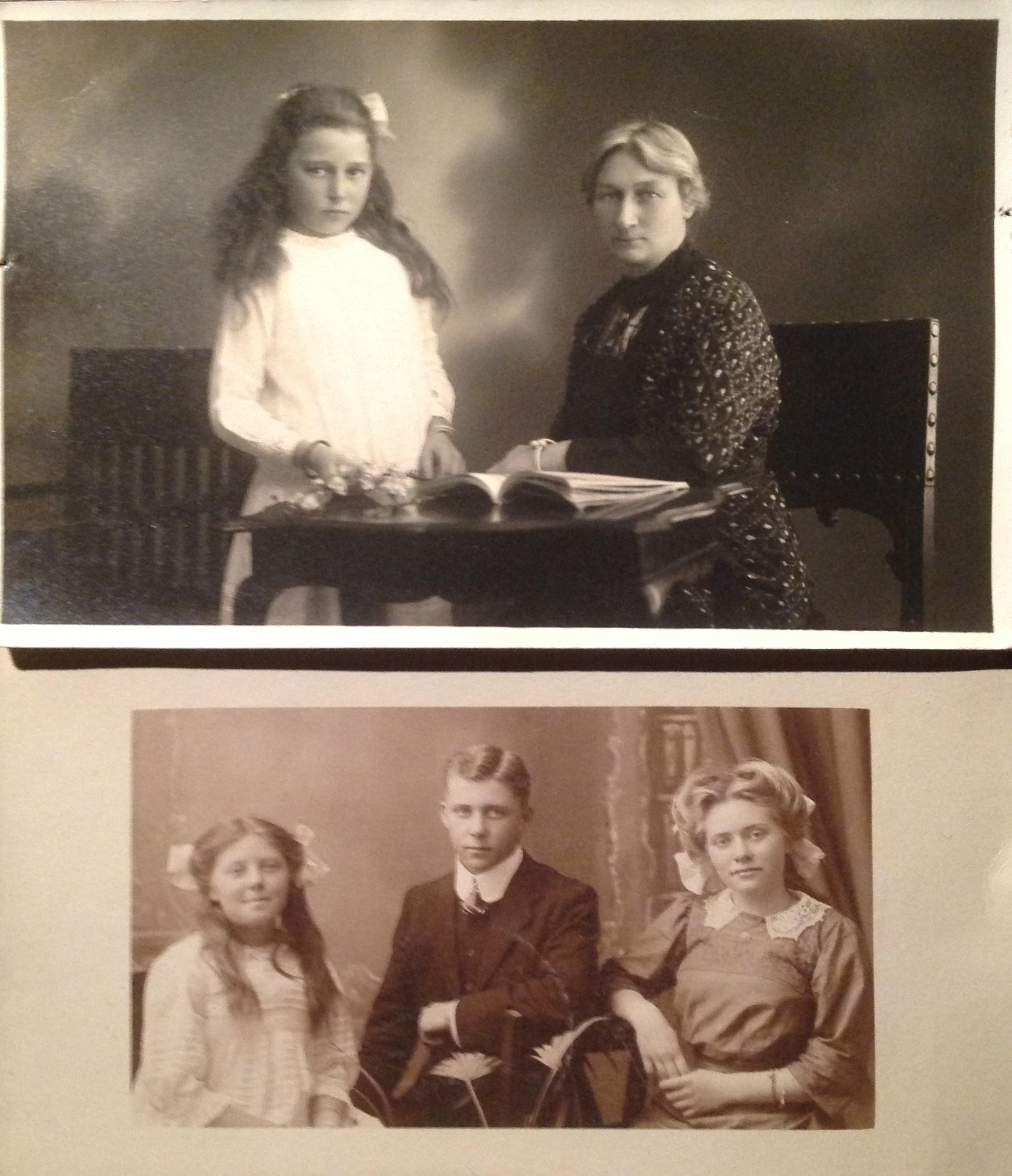

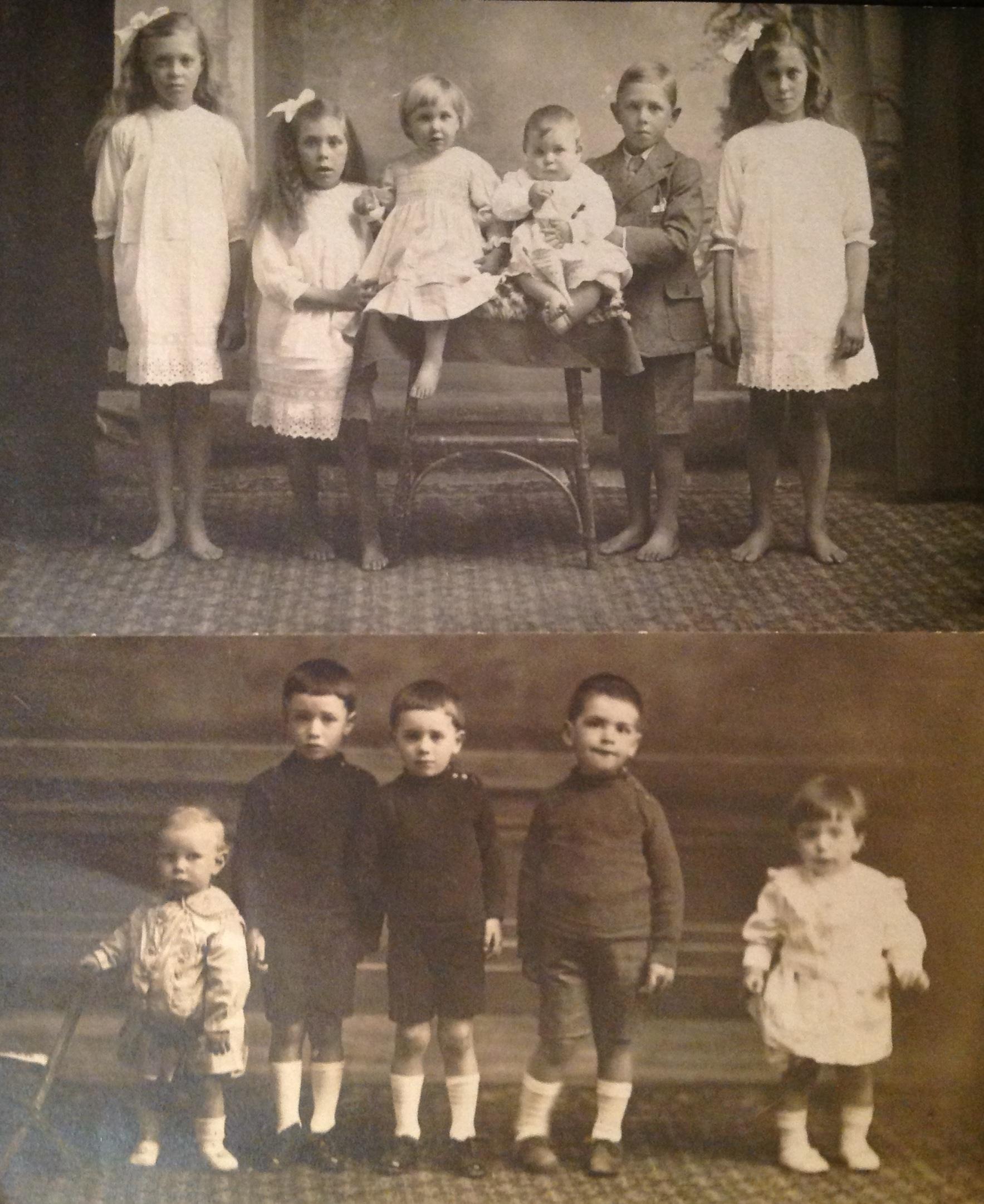

Top: Sitters unknown. Photograph by Pretoria based photographer Otto Husemeyer (May 1915). Bottom: Viljoen children – Bredasdorp – 1911. Photographer unknown – more than likely taken at home by a parent.

Photo postcard paper stock was first advertised by Kodak in the USA during 1902. During 1903, Kodak produced the model 3A folding camera that created postcard size negatives, making it easier for photographers to print directly onto postcard paper. These cameras would only have reached the South African market several months later. It is however suggested that South African produced RPPCs between 1903 and 1910 are not that common. In South Africa, the popularity in this photographic format only increased post 1910.

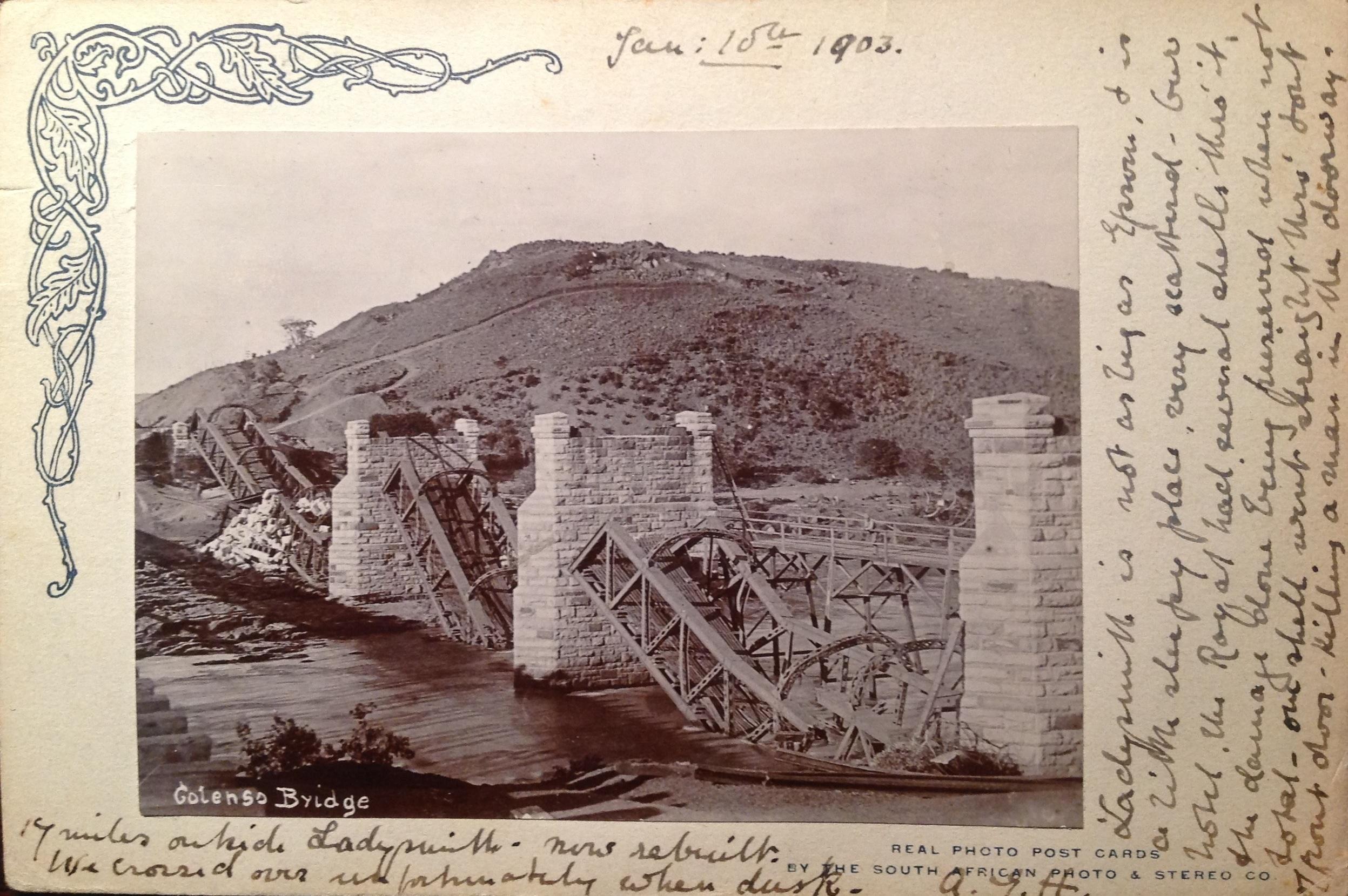

The earlier version of the RPPC was a photograph that was pasted on a stiff paper and sent through the mail (see image of the Colenso bridge below). These forerunners of the commercialised RPPC would therefore typically date from before 1904.

Example of an early Real Picture Postcard where the original photograph is pasted onto a card. Produced by SAPSCO – dated January 1902 (Colenso bridge - Boer war related).

The affordability and ease of producing these new photo postcards quickly made the traditional cabinet cards format obsolete. The clear majority of RPPCs were created in black and white, although some images were hand coloured after printing. Interestingly, a relatively small percentage of social/portrait related photographs ended up being put through the postal system (used as a postcard). They may have been posted in an envelope or were simply handed to loved ones who then placed them in family photograph albums.

Difference between printed postcards and real photo postcards

Although the history of the printed postcard is intertwined with that of the RPPC, it is important to understand the difference between the two versions. Both versions contained space on the back of the card for applying a stamp, address and a message.

- Printed Postcards: Mass-produced mechanically on printing presses. Not all printed postcards have their origin from a photograph, in that printed postcards also include drawings and paintings that have been mass produced into postcard format. Many printed cards, however, started as photographs before being converted into plates or screens stamped out by machines. Such cards were produced either by a company employed photographer who would receive a request to photograph certain locations, or local merchants or photographers would provide an image to a printing/publishing firm to produce postcards in bulk from the photograph provided. Larger print runs resulted in lower print costs per unit, resulting in vast number of cards being produced of a single image. Today these early postcards, with their immensely diverse range of subject matters, are highly sought after by postcard collectors, each with their own area of collecting interest.

- Real Photo Postcard (RPPC): Following the success of the printed postcard, the RPPC was however not mass produced. They remain true photographs produced chemically from a negative onto photographic paper with postcard backs. The production process was more direct than the procedure of the printed postcard. Typically, photographers developed the film themselves and then printed the photos from the negative onto the photographic paper. Their popularity outlived that of the printed postcards until around the 1930's. No longer a popular format, they were however still produced, to a lesser extent, well into the 1950's.

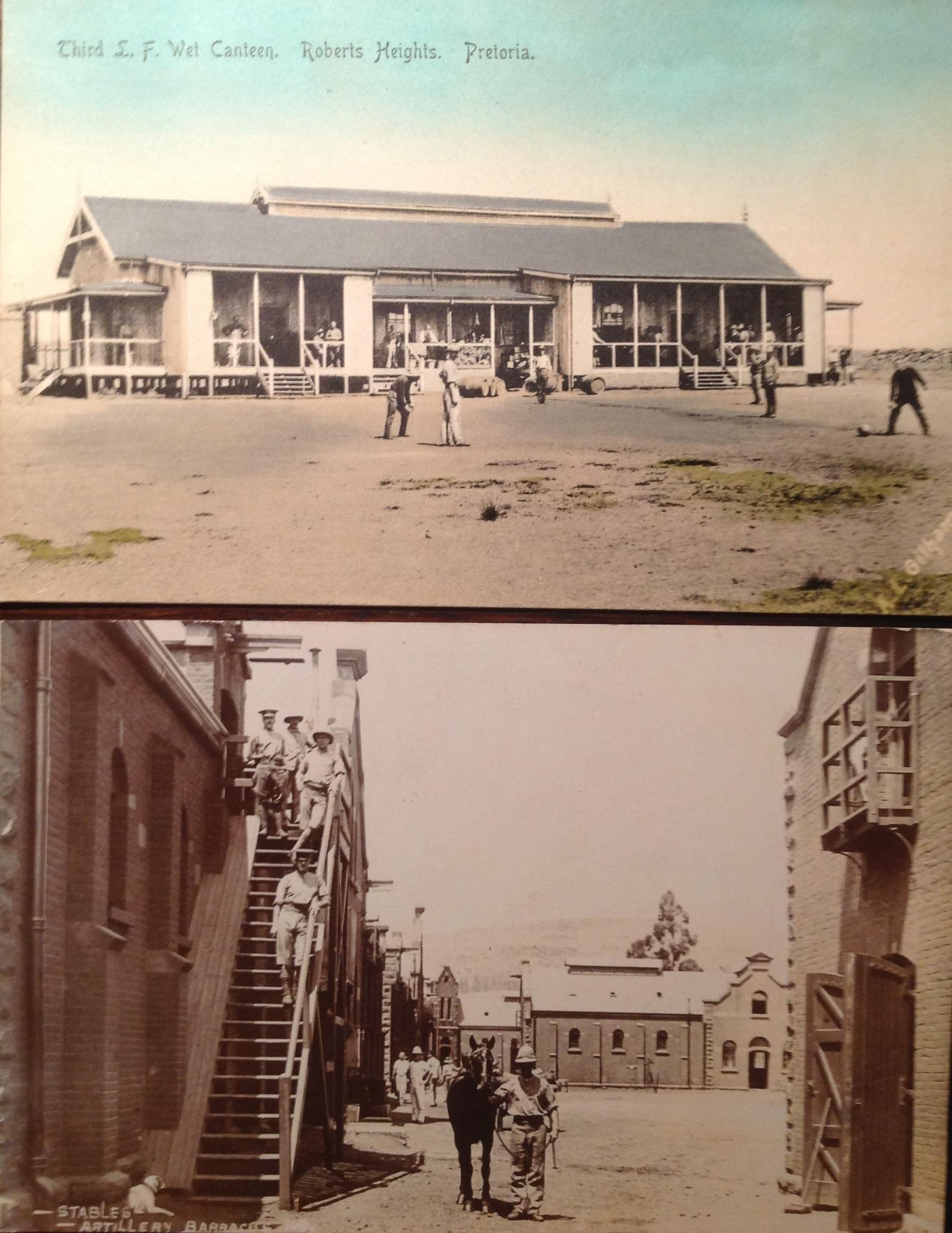

Example of printed versus real picture postcards. Top card would have been printed in bulk. Unusual for the photographer AL Gilham’s details to have been applied on front of the card. Card at bottom is a Real Photo Postcard of the artillery barracks in Pretoria as produced by SAPSCO. Lower numbers would have been produced of this card compared to the top card.

Identification of RPPCs

RPPC images are fresher and clearer compared to the printed postcard that typically contains a grainy pattern. RPPCs have a smooth shining surface. Captions on RPPCs are often also hand written.

What complicates research when using the RPPC is that the photographers did not always have their names applied on the card.

South African produced RPPCs can be identified and confirmed as being South African where the photographer has either applied a rubber stamp on the back providing his details or where it can be determined from the address, names of the sitter/location or postmarks that may have been applied. In exceptional instances the photographer would have pre-printed his details on the card. Photographs produced by amateurs are more difficult to identify without any details captured on the back.

Although it is not clear when photographic postcard stock was first produced in South Africa, it is safe to assume that between at least 1904 and 1910 that such stock would have been imported from both Europe and the USA.

RPPCs may or may not have a white border, or a divided back, or other features of postcards, depending on the paper the photographer used.

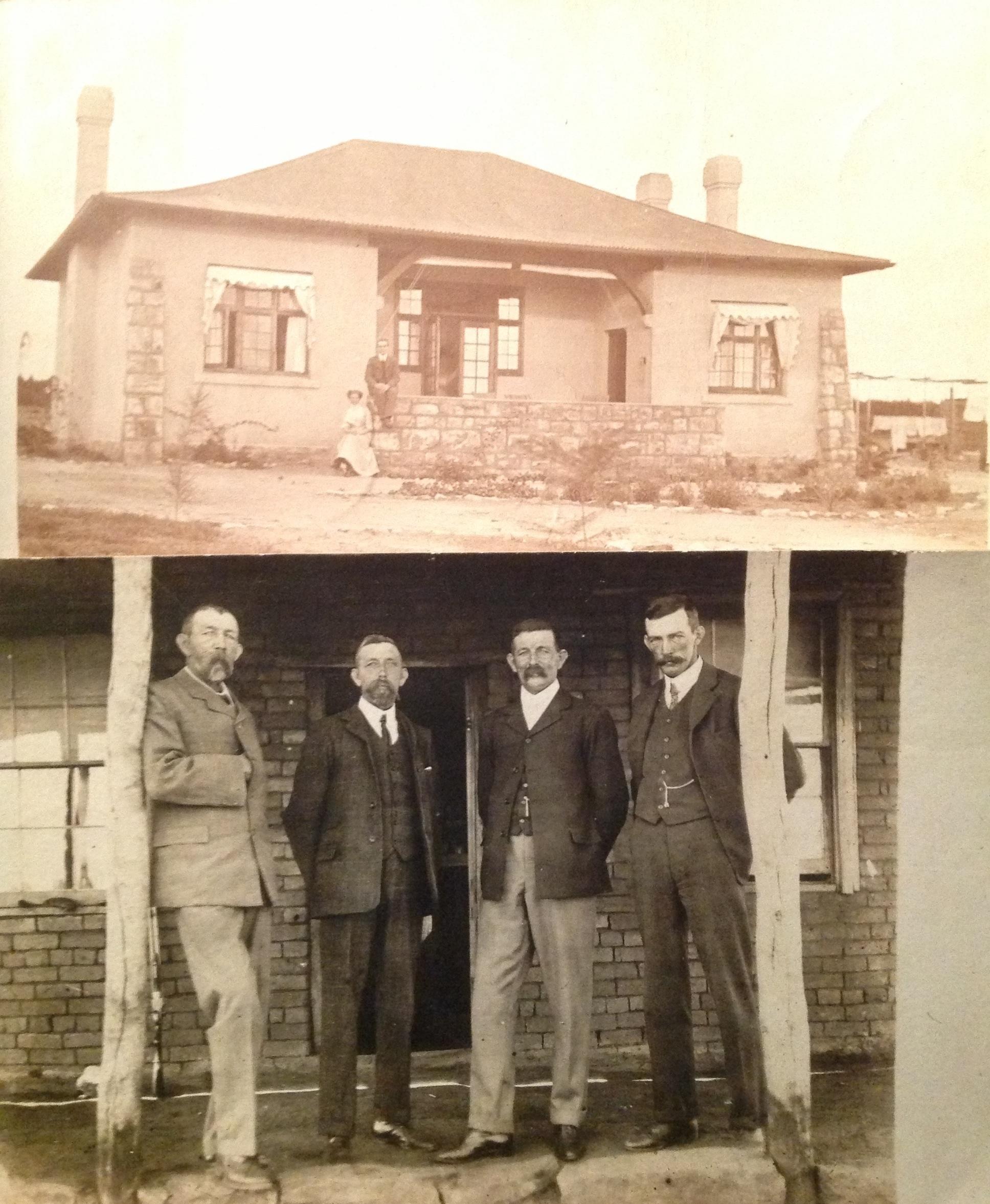

Top: House in Rosebank – Johannesburg. Photographer unknown. Bottom: Unknown men at a house in Pretoria. Unknown amateur photographer.

Who produced these Real Photo Postcards?

RPPCs were produced by both professional photographers/publishers and avid amateur photographers. View cards (street scenes, market places, buildings, natural disasters etc.) were produced in small batches by professional photographers/publishers that either sold them out of hand or to local merchants. These cards have become of great interest to both postcard collectors as well as photographic researchers.

The better known local RPPC producer of such view cards was SAPCO (South African Photo & Stereo Company) based in Johannesburg. Although less cards would have been produced per image as compared to their printed counterparts, these cards are higher in number compared to social/portrait images produced by either professional or amateur photographers.

In the handful of books published on South African postcards, no emphasis is placed on the difference between RPPCs and printed postcards. SAPSCO is also not acknowledged in these publications as a real photo publisher. Further research is required into SAPSCO’s business model at the time.

Photograph produced by Happy Snaps in Durban. Card especially of interest due to the car included. More than likely taken by a long term beach front photographer. Parties unknown.

From around 1906 to the 1930's it was common for South African studio photographers to produce photographs of their clients on postcard stock.

Ironically studio or amateur produced RPPCs are of little, if any interest to the general postcard collector. They remain mainly of interest to photographic and social history researchers. The focus of this article is therefore mainly on the social aspect, namely photographs of people produced in studios or by the amateur photographer.

Left: Photograph by Pretoria based photographer Otto Husemeyer (May 1915). Right: Baby Botes (Nee Joubert) – photographer unknown. Cannot help but to wonder whether the composition was intentional considering the similarity in patterns on her dress and on the building behind her.

Social aspects

People, from all stages of life, have always formed the principle subject of the photograph. The desire to have likeness of family and friends captured photographically has been the main motivation behind camera purchases over the years. Although some photographs remain formal, RPPCs are most desirable where they display military or other uniforms, disasters, cars, pets and children’s toys.

Standerton floods during January 1911

Potchefstroom camp April 1927. Armoured train group.

With the odd exception, photographs taken by amateurs rarely include images of documentary significance. Due to the studio portrait photograph in RPPC format not being in high demand they can be picked up at very reasonable prices.

Messages contained on some of the cards are also of interest and become a separate field of study. On the back of one of the photographs presented in this article, reference is made to a couple that are recovering from “the fever” and that 7 other in town have also been affected by this fever.

Real photo postcards remain a rich source of both visual and social historical interest.

Back of the card states: “My first photo taken” which explains poor composition as well as the lady being out of focus. Addressed to a Miss E. Clark in Cape Town.

Photographs of unknown children by JD Toerien from Robertson Circa 1918. Toerien was a long standing photographer in Robertson in that early Carte de Visite format photographs taken by him have been identified.

All photographs included in this article form part of the author’s photographic research collection.

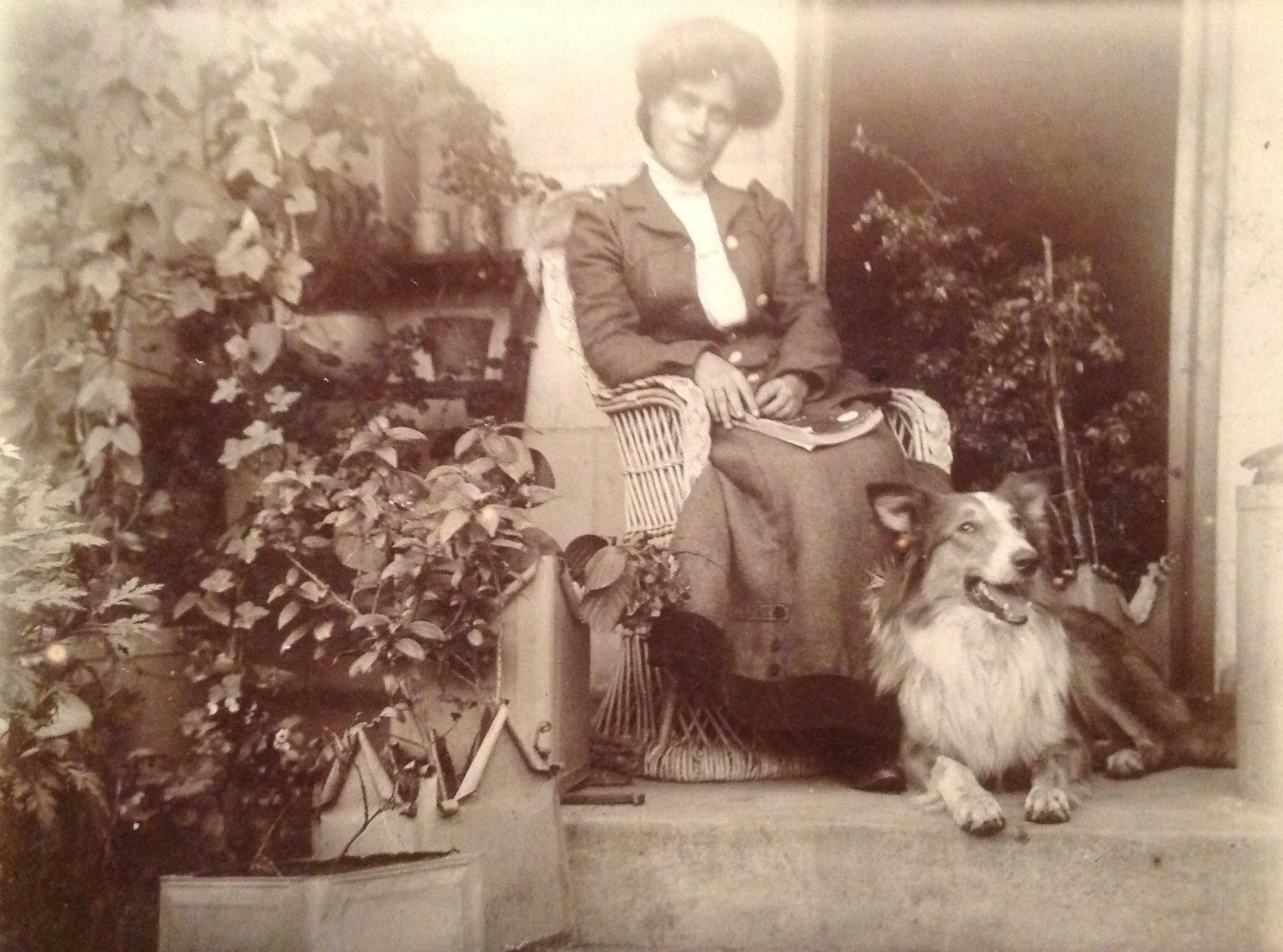

Description of two images at the start of the article: Left: Margaretta Joubert (by unknown photographer). Right: Sitter unknown – photograph by Pretoria based Aug. Blaettler.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources:

- Bogdan, R. & Weseloh, T. (2006). The Real Photo Postcard Guide – The People’s Photography. Syracuse University Press. New York.

- Coe, B. & Gates, P. (1977). The snapshot photograph – The rise of popular photography 1888 – 1939. Ash & Grant. London.

- Phillips, T. (2000). The Postcard century – 2000 cards and their messages. Thames & Hudson. London.

- https://www.collectorsweekly.com/postcards/real-photo

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_photo_postcard.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.