J. B. Taylor’s A Pioneer Looks Back is one of those understated memoirs that rewards careful and sympathetic reading. It is not the self-promoting autobiography of a dominant Randlord, nor a triumphalist corporate history written to secure a legacy. Instead, it is the reflective account of a man who was present at the formative moment of the Witwatersrand, accumulated capital swiftly and intelligently, and then stepped aside while the goldfields were still young.

J. B. Taylor was South African born, and that grounding gives his narrative its distinctive texture. He writes not from the imperial centre but from within the social and economic networks of southern Africa itself. Intelligent, affable and plainly well liked, Taylor followed the familiar late nineteenth-century path to wealth — diamonds at Kimberley, gold at Barberton and Pilgrim’s Rest, and finally the Witwatersrand. Luck, he freely admits, played its part; judgement and timing did the rest.

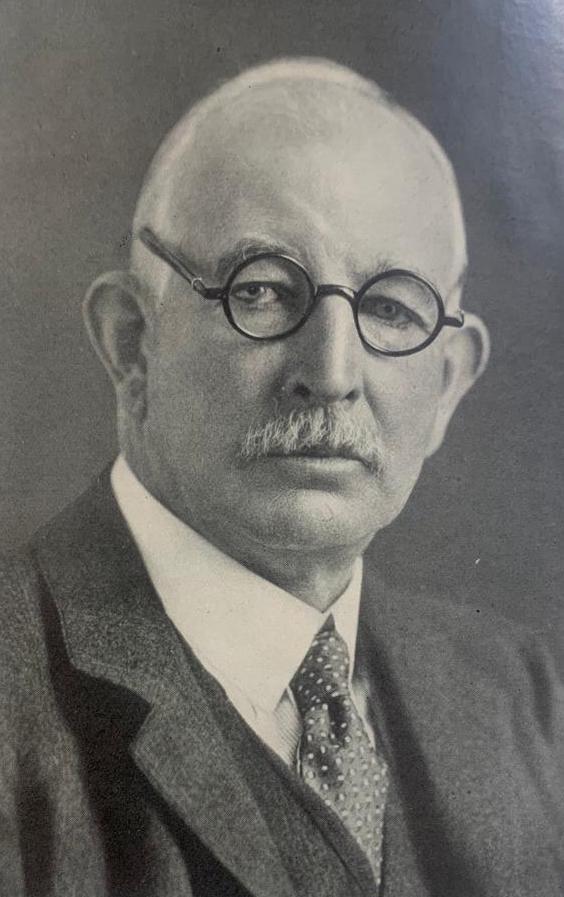

JB Taylor

His early association with Alfred Beit proved formative. Beit’s reputation for fairness left a mark on the young Taylor. A Grand Tour of Europe was followed by the sobering recession of 1882, which left him financially exposed. That early reversal lends weight to the success that followed when he and his associates turned to the Witwatersrand and, through what became known as the Corner House group — a pointed play on the surname of Hermann Eckstein — made a second and far larger fortune in gold.

Taylor moved easily among figures such as Paul Kruger, Cecil Rhodes, Percy Fitzpatrick, and Julius Wernher. As a confidant of Kruger and intermediary between the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek government and mining capital, he observed at close quarters the tensions that culminated in the Jameson Raid and the Anglo-Boer War. He was also instrumental in shaping Rand institutions, notably as founder of the National Bank of South Africa in 1891.

A particularly significant chapter in the memoir deals with the founding of the Chamber of Mines and the vexed question of the dynamite concessions. The South African Republic’s concessions policy was intended to stimulate local “critical industries,” but in practice it bred monopoly and resentment. The most controversial of these monopolies was the dynamite concession, initially associated with Alois Hugo Nelmapius (1847–1893), whose career represents the speculative flip side of Taylor’s own. Nelmapius overreached and died insolvent, his creditors receiving fifteen shillings in the pound — a stark reminder that the concession system could destroy as readily as enrich.

Control later rested with Eduard Lippert, and Taylor makes clear that Lippert did not meaningfully establish local explosives manufacture in the early years. Instead, Nobel products were imported, repackaged, and sold on to the mines at what were widely regarded as abnormal and exploitative profits. The newly formed Chamber of Mines emerged, in large part, as a protest against this situation. Yet the Chamber could do little more than protest. The monopoly remained entrenched.

Taylor records, almost casually, that he fell out with Lippert over the matter — and that Lippert never spoke to him again. The anecdote is revealing. There is no bitterness in Taylor’s telling, merely observation. He does not moralise about the system. He presents it as part of the accepted fabric of the time: influence, monopoly, opportunity. Morality was not the dominant currency in either Johannesburg or Pretoria. Taylor himself was driven by the same impulse as his contemporaries — to seize opportunity, to take risks, to make his fortune while youth allowed it. His memoir is the view of the man on the spot: observant, good-humoured, pragmatic, and untroubled by retrospective ethical scrutiny.

Equally important is his recognition of the technical foundations of Rand success. Taylor gives due credit to the American engineers who solved the deep-level challenges of Witwatersrand mining. His discussion of Hennen Jennings and particularly Gardner Williams highlights the importance of imported engineering expertise and a problem-solving culture capable of confronting depth, water, and scale. In this respect, the memoir offers more than anecdote; it preserves a contemporary understanding of technological transfer at a critical moment.

Taylor retired from active business at the remarkably young age of thirty-three and left South Africa before the political storms broke. He later returned in 1917, settling in the Cape, where hunting, fishing and travel filled his remaining decades. He was also a founder member of the Wanderers Club, when it stood on the site later occupied by the new Johannesburg station in the 1950s — a reminder that his life was woven into the social as well as the commercial fabric of early Johannesburg.

Old photo of the Wanderers from above

Born in 1860 and dying in 1944, Taylor’s lifespan bridged frontier conflict, the rise of the Rand, the Anglo-Boer War, the First World War and most of the Second. He both shaped and benefited from the British imperial economy in Africa.

This gives the 1939 first edition of A Pioneer Looks Back particular poignancy — and increasing collectibility. Published in London on the eve of the Second World War, the book already described a vanished world. The Rand pioneer era had passed; Europe was again at war. Unsurprisingly, the memoir slipped quietly from public attention. Today, the first edition is valued not only for its content but for its timing — a reflective voice speaking at the precise moment when both a personal and imperial chapter closed.

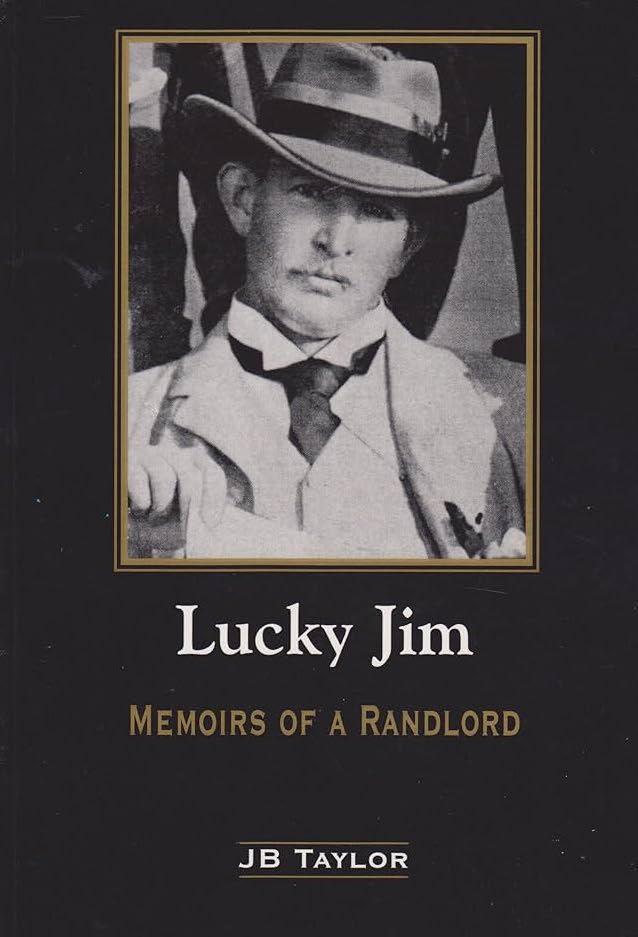

When Stonewall Books republished the memoir in 2003 as Lucky Jim: Memoirs of a Randlord, accessibility was restored. Yet the authority of the 1939 edition — contemporary, elegiac, slightly out of time — remains distinctive.

Book Cover

It is fitting that Taylor’s youthful portrait hangs at Northwards. Like the house itself, his memoir captures a Johannesburg that was still becoming — a world of risk, personality, opportunity and unapologetic ambition. The book is illustrated with some 25 photos of peoples, places, scenes and events adding texture, authenticity and a visual archive.

JB Taylor portrait

For readers, historians and collectors interested in the early Witwatersrand, A Pioneer Looks Back remains quietly indispensable: not because it is morally searching or analytically severe, but because it is the voice of a young man who was there, who prospered, and who later told the story with charm, candour and remarkably little regret.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also a previous Chairperson of HASA.