Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Human behaviour that deviates from the norm has always incurred curiosity. It is thus unsurprising to discover that photography was used to capture images of the mentally ill as early as 1848.

The photography of mental illness can be defined as the practice of depicting people whose behaviour has been deemed markedly abnormal by their contemporaries. Photographs taken of the mentally ill once served to document case histories, but occasionally also as therapeutic instruments. The patient seemingly only needed to recognize himself in the image of insanity and to note his difference from the images of normalcy in order to restore himself to reason and sanity.

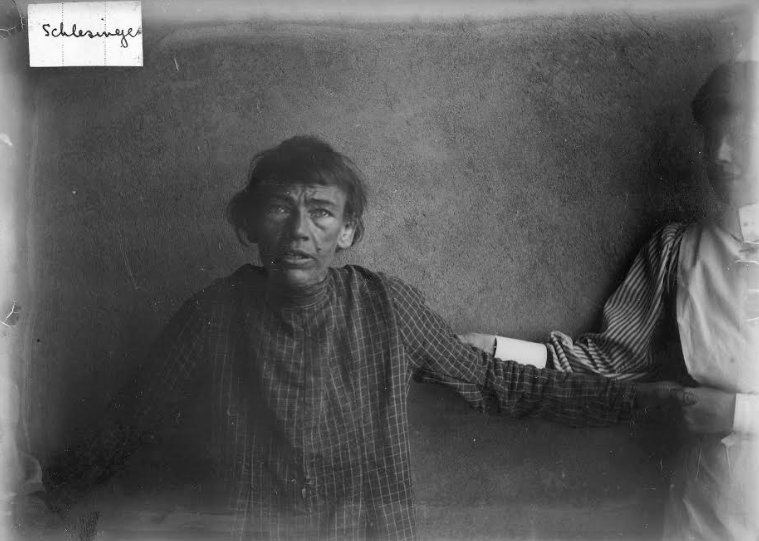

Some 100 photographic glass negatives, recently donated to the author, are images of individuals, or small groups of people, many of whom are clearly mentally ill and held in some sort of captivity. These images, in all probability were taken in South African mental asylums and some prisons.

A prominent photo from the collection

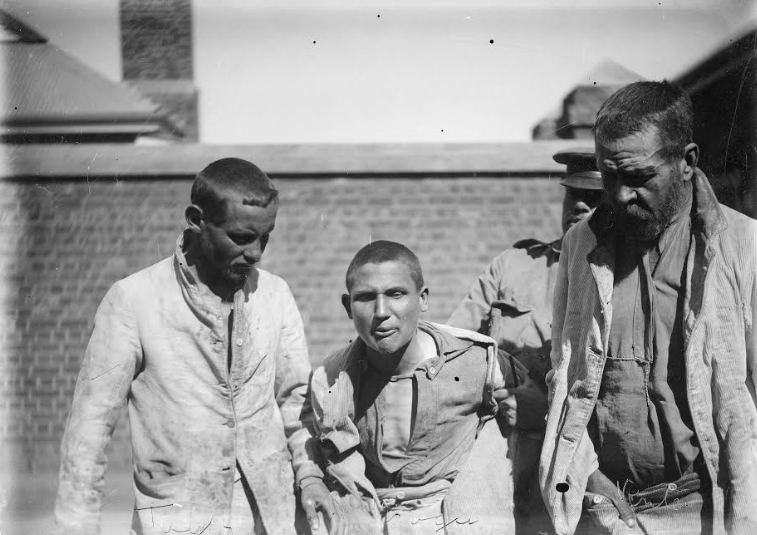

These images date from between 1908 and 1912. Both the location and the photographer details are unknown, yet these unusual images leave the viewer saddened, surprised, shocked or even in denial as in some cases they portray images of clearly abnormal behaviour – a dimension of human pain and imbalance that the majority of normal functioning human beings are not exposed to on a daily basis. The majority of these images, many of them with the patient’s name included, leave one curious and wondering about individual circumstances and conditions the subjects found themselves in.

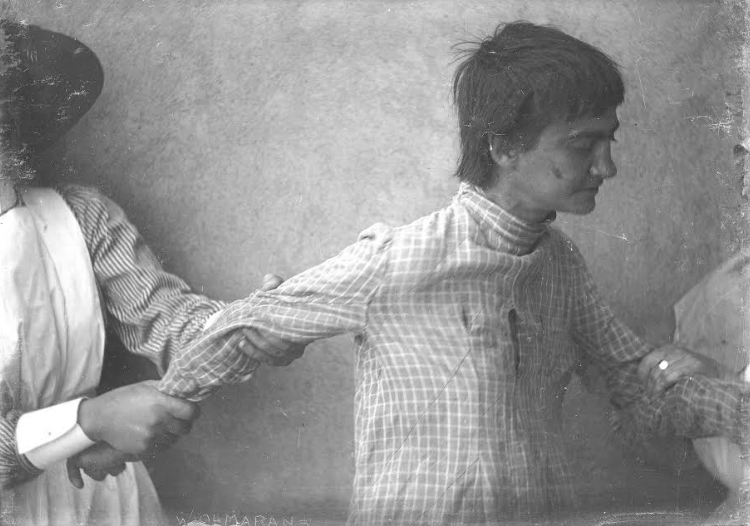

Some of the images are of patients photographed in the nude. In the background of some images female nursing staff in uniform, or what seems to be a prison guard, can be seen (see main image). Other images show patients sitting in a courtyard or a man in a prison cell bed, surrounded by other beds. With many of the images one gets the impression that the individuals did not pose willingly. Even though most images include the names of the patients, the actual individuals photographed remain a fairly elusive and abstract entity. The reality of these images is that one will never know all the circumstances surrounding the moment at which each photograph was taken and what contributed to the construction of each image.

Nursing staff in uniform can be spotted in many images

Another photograph revealing uniformed nurses

At one stage it has been suggested that madness and criminality were congruently charted. The earlier view of the mentally challenged was that the visual typology of the insane was wild and that the pathology was not only located in the mad person’s skull shape and size but also in his/her facial characteristics.

Photography’s early status as an objective medium has provided it with a particular authority when representing to us the human form in all of its manifestations. Early photographic studies were used to set up indices of normalcy and deviance. Images of the insane were therefore not so much aesthetic as illustrative.

Photography of the mentally disturbed, prior to 1920, provided a captured visible dimension – the notion that external symptoms unequivocally indicated a particular illness or disturbance. With the abandonment of this approach during the early 20th century, psychiatry’s interest in pictures of mental patients diminished as they were hardly objective clinical records. This makes the find of these early historical images even more significant – images that were more than likely not meant for public viewing in the first place.

Images were more than likely not intended for public viewing

It has been suggested that criminal photographic archives gave birth to psychiatric photography, or photography of the mentally ill. This is however unlikely, as mugshot photography of the criminal was only started during the late 19th century in France.

The first image of a mentally ill patient was taken by Frenchman Jules Baillarger during 1848, just 21 years after the invention of photography. Just over two decades later, in 1876, the first medical textbook to employ photographic illustrations (written by Henri Dagonet) was published. A British medical practitioner and amateur photographer, Dr Diamond, even exhibited some portraits of his patients at a London photographic society exhibition. Charles Darwin also used photographs of mental patients for his book Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), both for study purposes and, occasionally, to illustrate his arguments.

One of the original purposes of psychiatric photography was to ease a growing public anxiety with respect to the increasing dangers associated with an ever-expanding social arena.

Psychiatric, as well as criminal, photography and physiognomy (judging human character from facial features) promised to educate a nervous public about who they could and could not trust on the urban scene.

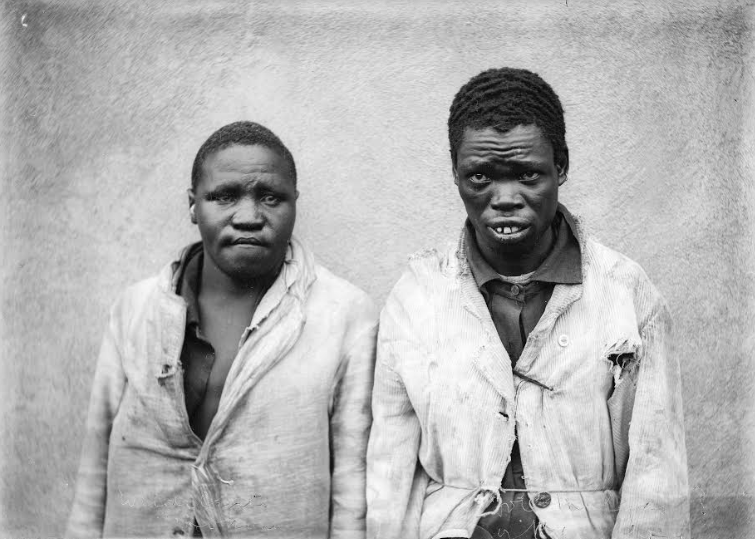

The question eventually asked was: “is the state of mental illness readily available to the “naked eye” of the camera?” It became clear that images of the mentally ill provided no scientific base to make an informed psychiatric diagnosis. The lady on the left in the image below certainly does not seem mentally disturbed in any way – at least on the surface.

Is the state of mental illness readily available to the “naked eye” of the camera?

The reliability of an image is based more on how well it corresponds to our belief system than on how neatly it conforms to the “actual” physical dimensions of the object it represents. In the early days of photography, insanity was not conceptualized as an “invisible” disease.

Photographic images of the nineteenth and early twentieth century therefore created more of a visual model rather than representing a psychological state. Visual types were constructed in that the photograph focused on the face of the deviant.

Few therapeutic options were available and practitioners acted mainly as custodians with patients being left to spend the rest of their days within the bleak walls of institutions.

It is known that prisons served as temporary holding areas for the mentally disordered due to mental institutions being full. This might explain why some of the images seem to have been taken within the confines of a prison.

Sadly, the confining of the poor and homeless in early South African state mental institutions was a means by which the state could maintain social control. Practitioners used psychiatry as a disciplinary tool to control violent African resistance to the colonial government’s often racist policies.

It has been argued that psychiatry was used as a prime tool during colonization, having as it did the mandate to manage unruly and disruptive members of community. Psychiatry certainly assisted in providing a rationale, under the guise of science, for existing practices of social control.

Looking at images donated to the author of inmates in these South African institutions, the question arises, - which individuals were incarcerated due to some form of mental disorder and which were incarcerated due to social control or group oppression?

Tragically, many asylum inmates actually suffered from developmental and not mental disabilities, but an asylum was a convenient place to put them “out of sight and out of mind”. Human rights were certainly not a consideration then.

At the time of unionization, South Africa had eight mental institutions that accommodated around 1692 “European” and 1932 “non-European” patients. Mentally disordered individuals were either institutionalized voluntarily or involuntarily (through a court of law). Both instances however required the evidence of two medical practitioners.

Although photographic images were intended to substantiate a particular view of a condition, they could hardly have been an objective clinical record. So much so that their scientific value became suspect, resulting in their rejection as valid research material. Yet, only a few of these images leave us with some impressions on what a mentally disturbed person seemingly looked like.

* * *

The photographic glass negatives that led to this article were donated to the author by Lappe Laubscher. Sources consulted: Mainly internet based articles by Prof R. Emsley, T.F. Jones and Kathryn Fraser.

Note: Terminology with regard to the mind is extremely subjective. Words such as lunatic, imbecile, insane, idiot, mad, defective and feeble-minded were used prior to World War 1. By the mid-twentieth century individuals were referred to as retarded, neurotic, disordered, unhygienic and unstable. It was only much later that words such as schizophrenic, depressed, psychotic or mentally ill came into use.

This article was also published in the Africana Society (Pretoria) annual booklet.

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.