Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Excerpt from his book 'We Wander the Battlefields'. Submitted by Pam McFadden, Curator of the Talana Museum. Should you wish to read the entire book it is available here.

In 1978 an English / American film company, Samarkand came to South Africa to make the film Zulu Dawn, about the worst military defeat ever suffered by a white British army at the hands of a black army in South African history. This happened at a place called Isandlwana in Zululand in 1879.

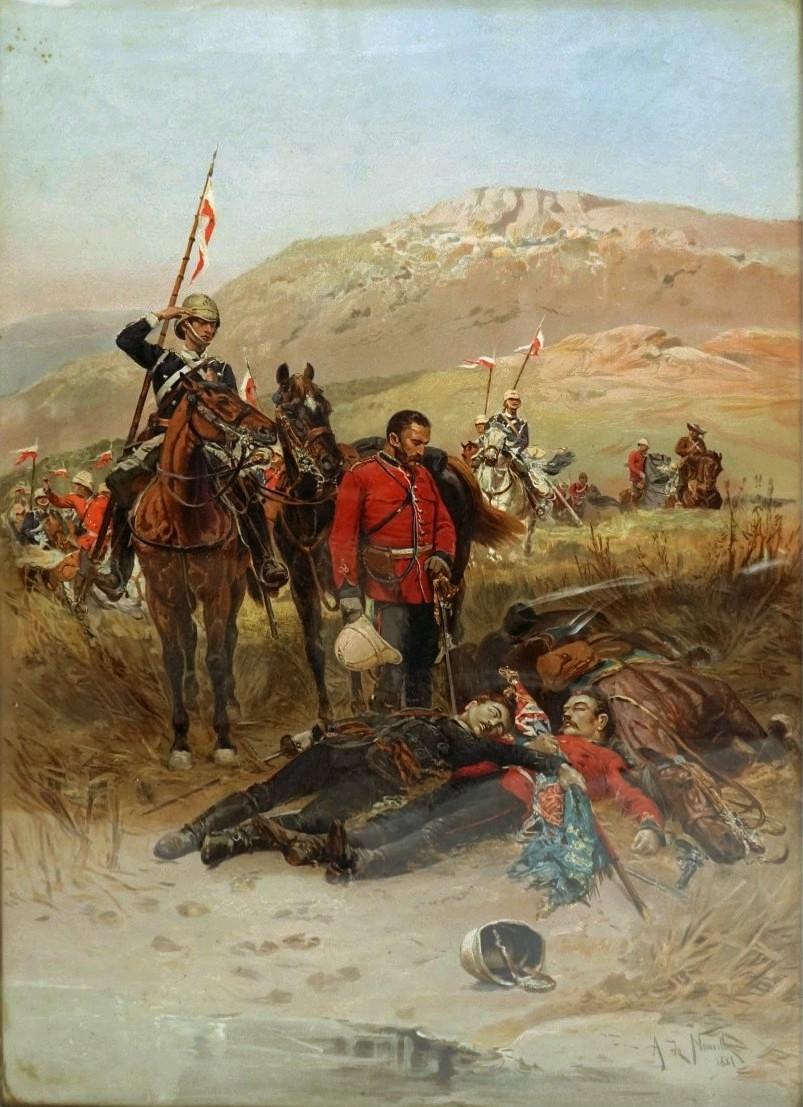

Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

Unfortunately nobody on their production staff had any knowledge of the Zulu War or of this battle. I had contacted them because I was concerned that they would fly the incorrect flag in the battle sequence, which was not the Regimental flag of the 24th Regiment. This was incorrectly painted by the Victorian painter Alphonse De Neuville in his painting The Last Sleep of the Brave.

Last Sleep of the Brave (Wikipedia Commons)

It was the Queen’s Colour, the Union Jack which had been taken to Isandlwana, the Regimental Colours remained with HQ staff at base camp.

Concerned about this, I phoned the production office in Pietermaritzburg to see if the saving of the Colours was going to be featured in the film. When this was confirmed I asked them to describe the flag being saved. It was the wrong one, and I had pictorial evidence to prove it. That afternoon the Art Director came to our home and I showed him what I had, which resulted in me being offered a job on the production.

Fortuitously, as the firm I worked for had just folded, Samarkand then contracted me as the historical advisor and later as the military advisor as well. I had served in the South African Commandos for over 15 years at that time and I also had an extensive collection of military weapons and a long and passionate interest in the military history of South Africa.

I was put in charge of the principal actors and all 400 extras, to teach them the correct drill procedures of the period – very different from what they are today.

My work quickly snowballed into location-finding, set-dressing, voice-overs, still photographer and even assistant director and finally to play the part of Lieutenant Cavaye, one of the British officers who was killed.

Some perks were the use of a company car, a motor-cycle to enable me to move quickly between sets, and flights in a helicopter to choose locations (keeping in mind the Director’s needs regarding access, lighting etc.)

Well-known actors in Zulu Dawn included John Mills (a true gentleman), Peter O’Toole, Burt Lancaster, Dai Bradley, Bob Hoskins, Christopher Cassenove, Denholm Elliott, Simon Ward, Paul Copley and many others.

Movie Poster

We also required in excess of 1,000 Zulus at times. These were drawn from the local workforce, which was not very popular with the sugarcane growers. It was rather amusing that the scenes demanded that the Zulu actors run bare-footed over the rocky ground – something they were not used to now and which caused chaos in one huge massed charge when it was noticed that one or two were wearing green ‘tackies’ (sneakers).

I was constrained, to a certain extent, by the underlying purpose and need of the company to “put bums on seats”. This meant including a romantic interest between Colonel Durnford and Fanny Colenso, the daughter of Bishop Colenso of Pietermaritzburg.

Trish recently found a magazine article, Film and the Zulu War by Ian Knight, in which he writes, referring to Zulu Dawn: And yet the historical accuracy is far better than average, the battle scene breath-takingly spectacular, and the sense of location superb. Many of the scenes were filmed on the spot, including the river-crossing at Rorkes Drift-though this was filmed in reverse, the column crossing from the Zulu side to the real Natal side!”

In going through the large amount of paper I kept from the making of the film, I found these “observations” I made at the time. It may answer many questions.

The cloud of grey smoke cleared away with the echo of the gun shot. The crowd of senior film personnel stood back watching the test firing of a British field gun made expressly for the film Zulu Dawn. To me, as military advisor, it was incredulous. The gun did the most remarkable gyrations along the ground, defying realistic imagination. By the looks of delight on most of the faces about me, the antics of the gun were lost to most but me.

What happened in sequence went something like this:

1) the gunner chopped down on the lanyard (dummy) in the customary manner;

2) instantly the gun was fired electrically – remotely triggered by a special effects man;

3) half a second later the gun ran back in a delayed recoil and,

4) instantly and entirely unassisted by the now unemployed gunners was thrust forward to position (1) by its own concealed mechanism.

I protested to the director that this sequence was impossible and explained why. A hurried meeting was held with the special effects team who admitted that the device they had made and brought from Germany was made to suit a modern gun with a recuperator – not an unsophisticated muzzle loading British field gun designed well over 100 years ago. The system could not be adapted to work any other way due to the time factor, the only choice left was Hobson’s! Perhaps some deft cutting by the editor may be able to mollify these sequences, otherwise you gunners please don’t laugh.

But by and large Zulu Dawn has been made as historically and militaristically accurate as the strictures of time, money and the dramatic content of the story will allow and Douglas Hickox, the director, and all the other hard-working production crew, kept this constantly in mind.

To this extent original locations were used wherever possible. I came to Zulu Dawn well after the production stage had commenced, with the result that to some extent the die had been cast on some issues, but shooting was still two months away and many inaccuracies were corrected.

The film script Zulu Dawn had been written by Cy Enfield and Anthony Story many years ago, soon after the very successful release of Zulu in 1964.

Zulu Movie Poster

The actor Stanley Baker had bought it with the intention of making this a vehicle for his own acting talents – but by the time he died this had never been done. With his death the script became available once again and Samarkand Motion Picture Productions obtained the production rights.

Naturally, being an out-of-doors film, good weather was vital so a winter schedule was opted for. This presented several problems for the sake of consistent sunshine. As we all know, the period we were filming was of a Natal in mid-summer with all its greenness, full rivers, thunderstorms and mists, but we would have brown veld, clear skies and rivers with little water in them.

Added to this, extras dressed for summer found the chill winter winds bit through their thin garments, and the near-naked Zulu extras suffered even more.

The concensus of opinion however was that the majority of people overseas, who have any preconceived opinion of South Africa, picture it as a ‘Khaki” country, so that piece of licence was accepted.

I would like to make one important point here which an historian must accept when he starts to get on his high horse over some point or other. The Director’s word is final. A film must sell to be a success. The average film-goer is there to be entertained. If he or she is, they pass the word along, and so the turnstiles roll and the producers – those who put up the money – are happy.

In an enormous production like this, both in size and expenditure, those turnstiles must turn a’plenty to keep the backers happy.

So, bearing this in mind, all things are subservient to the dramatic impact of the story. With Zulu Dawn this too must apply, but wherever possible all due respect has been given to historical accuracy.

Zulu Dawn starts with the ultimatum being drawn up by Sir Bartle Frere, played by Sir John Mills. This is then conveyed to Cetshwayo, who does not comply with the terms and thus the British Army sets out from Pietermaritzburg for the Zululand border.

These scenes are historically simplified so as not to confuse the unknowledgeable and perhaps uninterested cinema goer, whether they be in America, Japan, Germany or Spitzbergen.

For convenience the first scenes shot were those of Lord Chelmsford’s sorties out from Isandlwana looking for Cetshwayo’s army whilst the British camp was attacked and destroyed.

These scenes were shot at Baynesfield near Pietermaritzburg. The soldiers had to look dirty, sweaty and tired after a long march. Helmets and webbing browned down with mud as was required by regulations to make them less conspicuous. Certain animal-drawn vehicles were insisted upon to make the column look big, although Chelmsford took little or none in reality. Also appearing here, and historically incorrect, is a section of 17th Lancers, as his guard. These had been ordered and cast before I came on the scene, and certainly they added an air of military pomp. In real life this unit only reached Natal in April, 1879. As to Lord Chelmsford’s escort, this was composed of mounted infantry, drafts from the 24th Regiment.

After several days at Baynesfield, where every morning we waited for the sun to melt the frost before we could make the scene look like summer, we moved the whole operation, including our vast mobile kitchen and canteen to Pietermaritzburg.

Here the army would be assembled before going to war, here the NNC (Natal Native Contingent) would get a smattering of training, here the volunteers would be introduced to the story and here the Commander-in Chief would review some of his troops. Needless to add all browned-down helmets and equipment had to look like virgin snow!

For this purpose, a squad of near company size was drilled solidly until they could present arms like a machine. The moment had come and Peter O’Toole, as Lord Chelmsford, regally mounted an off-white horse, approached with his Staff. Sergeant R Gill bellowed the appropriate command–there was a crashing and stamping of feet–and Chelmsford’s horse took off. Peter O’Toole battled to control the beast, but to no avail and he fell off – fairly gently, fortunately.

Peter O'Toole on the left

All credit to him, a hurried discussion took place; he would do it again and the men would go through the motions in silence. Next take–the same result, but Peter O’Toole kept his seat this time. He then drove the horse back to the redcoat ranks, but it remained very skittish, and finally threw him heavily and very nearly trampled him as well. This put Mr O’Toole in bed for a few days.

Another gaffe, which I had to concede to, was Lt Melvill inspecting the men’s rifles from right to left, which is the wrong direction. This was done for the sake of camera angles and the direction of the sunlight.

It was during this period that I read an amusing report in a local paper. Several of our extras proved to be enterprising young journalists hoping for inside stories, and one who had been in a day or two wrote about the sloppy marching and rifle drill he had been taught, nothing like the smart foot-stamping drill of the British Army. Furthermore he said we had concocted it all ourselves. He obviously hadn’t been present, or hadn’t listened, when I explained to all the new recruits that they would have to learn the authentic turns etc. of the time and forget about all they had been taught during their military training.

The scenes utilising the oval in Pietermaritzburg, which had been very skilfully redecorated to resemble a military assembly area, were concluded with a night sequence of the army on the move. This took three full nights of shooting. Now there can be few more pleasant places than Pietermaritzburg on a warm summer evening, but in June we were working in temperatures down to -5 ̊C and all night through. It was hard going.

Screenshot from the night sequence

Following this section I left for Dundee and Rorkes Drift with the 2nd Film Unit.

Now a movie of this size needed two complete film crews in order to accomplish the shooting in the allotted time and the second unit, directed by David Tomblin, had all the vast outdoor scenes to shoot, including the massive sequences at the Zulu Royal Kraal.

But to start with they had to shoot the invasion of Zululand at Rorke’s Drift, with all the paraphenalia of an army crossing a river into enemy territory, and a more dedicated and professional crew one couldn’t hope to meet with.

Crossing the river

Once again dramatic licence was used. Looking at Zululand across the Buffalo River, the countryside looks soft and peaceful, but looking at Natal from the Zulu bank, with the rugged Oskarberg or Shiyane looming straight up from the river bank, a far more forboding scene meets the eye, so for effect the filmed invasion is reversed – we invaded Natal from Zululand!

At this point we were troubled by the low water and also a modern building close to the river where the army had originally crossed, but downstream 600 metres we found a spot wide enough to make the ponts feasible and realistisic. These had been accurately built by a skilled crew, and reduced slightly from the originals to make the river seem much wider. A vast tented camp was set up across the river and an old drift crossing, opened up by an excavator, became our roadway for the 4-wheel-drive vehicles to cross. This track gave constant problems and needed frequent work to keep it negotiable.

We seemed to spend weeks on this sequence, during which our first helicopter crashed when the engine failed. The occupants were very lucky as only the skill of the pilot saved them from certain death.

Whilst there, the rocky and bush-covered slopes of the Oskarberg were used to shoot a number of small scenes of importance to the story. It was here that we had the helpful company of Mr George Buntting, the well-known historian from Fugitives’ Drift.

One particular incident stands out in my memory. Towards the end of these sequences a high angle view of the crossing was called for, showing Zulu scouts observing the British invasion. This had to be shot from the summit of the Oskarberg.

By now both film units and the whole crew were at Rorke’s Drift. I was asked by Peter MacDonald, the 2nd Unit Co-Ordinator, if I could guide a small camera crew to the summit early next morning. We would take four Zulu actors with us as well.

By 7.30 we were ready. We drove to a point around the back of the hill, completely surrounded in mist. Each person had a load to carry. We had two 35mm Panavision movie cameras and all their equipment. To my surprise, Peter MacDonald, who is not a big man, heaved a massive tripod on his shoulder and set out behind me up through the rocks and heavy bush into the mist. We made the summit, heaving and sweating, in three quarters of an hour and had to huddle in the lee of the rocks for nearly two hours until the mist cleared and we could shoot. It was the willingness of these two directors to muck in and do everything they expected of their team, that created a wonderful esprit de corps amongst the second unit. I don’t recall them ever taking one Sunday off once the filming got under way. What a farewell party they gave their unit crew in the final week! I will never forget it.

From here we moved to the battle area to be shot on the northern slopes of Isepezi Hill, about 18 kilometres to the east of Isandlwana. Whether or not permission was given or even asked for us to use the original battle site I do not know. Technically it could certainly have been used.

The hill used in the film

The monuments, graves and buildings could easily have been concealed, but one major problem could not be avoided. From soon after mid-day Isandlwana throws an ever-lengthening shadow across the battlefield. This would have created major problems from two points of view;

1) with big scenes it would take all morning and sometimes more, to set up a sequence, so shooting would take place late in the day, and

2) that massive shadow would cause serious continuity problems.

So, with some regret, we had to use a very different locale, a hill double the size of Isandlwana, and a plain heavily interlaced with deep dongas. On this field I now had to set up the battle sequences as near as possible to what took place in reality, and at the same time use the natural terrain as a local commander would use it.

I spent much time walking the area, if I couldn’t get to it by light motorcycle, and finally drew a set of maps laying out the whole sequence of events to represent the fateful 2nd of January, 1879. In the end Douglas Hickox chose to bring the perimeter in somewhat closer than I had suggested, for practical cinema purposes.

Next problem was to expect modern Zulus to emulate highly trained and hardened warriors of a century before. Many lacked any incentive to run, let alone charge on command. Their feet, in many instances softened by constant wearing of shoes, couldn’t take the rough ground. We eventually let them wear dark shoes or tackies in long shots. Much time was lost in trying to get these sequences to work, and it wasn’t until David Tomblin and his unit had a brainwave on the penultimate day of shooting, that we got something that really looked like a ferocious charge from our thousands of warriors. He found them an area of soft going with little or no rock or thorns, faced them downhill, pointed them towards home – the opposite direction of the British camp – placed all the prop trucks in a donga (a dry water course) in front of them, and then told them to do it right and they could go straight on home, but if any one of them didn’t run like hell, he would send them back to do it all again! There were also several crates of beer in the trucks for them – a powerful and successful incentive!

Zulu Charge

His “Go!” signal was two rifle shots fired over his head. What a headlong rush – it was incredible. Three cameras at different angles got it all and the Zulus went home.

Veld fire was a constant hazard and our efficient fire-fighting unit had a number of calls to deal with before the film was finally in the can. Many fires were required for the film... we lost count of the number of times one waggon was set alight for the cameras and as quickly doused once shooting was over. A trick of ‘special effects’ used for this was to use liberal amounts of contact adhesive poured all over it and lit. This burned most realistically for quite a while before the timber was seriously affected.

Authentic equipment proved to be a very serious problem however, one which was never completely solved. Martini-Henry rifles in any quantity were just unobtainable. Carbines and cut-down rifles, ex-school cadet drill weapons yes, but long rifles very few.

The set design department made a very authentic looking Martini-Henry reproduction in moulded foam polyurethane for drill purposes, which worked very well, but these obviously couldn’t fire, so in the battle sequences these were replaced with the shorter carbines which would fire blanks. Even these were in no way adequate quantity for all our soldiers, so men in long shots had all sorts of .303 rifles (all our blanks were black powder in this calibre), and I had to keep a constant watch to see that these were never seen close on camera. For specific close-ups the long Martini-Henry rifles were used.

The seven-pounder field guns do not resemble the authentic guns either. Firstly they were made to the size of the nine pounder, as the seven pounder looked too puny, and secondly the quoin elevating mechanism is utterly wrong, as they copied this from an illustration of a seven-pounder mountain gun.

Due to the size of Isepezi, the Zulu right horn, who came round behind Isandlwana to cut off the British retreat, had to be ferried in by bus. They were then assembled to make their dramatic entry to cut off the flight of Durnford and the survivors from the battlefield.

Burt Lancaster as Colonel Durnford, uses an authentic break frame Mk.vi Webley revolver. He had to do all this acting and action with a crippled left arm and he devised a way he could handle and reload this type of weapon, which he could not convincingly do with the solid frame Adams or Tranter of the period. He proved a fit and skilful rider and comes over well as the doomed Colonel.

Throughout the battle the guns caused problems and certainly some excitement too. The sequence where they are lost was all action and despite mishaps, no serious injuries were sustained.

At this point, it is important to understand the role of the Honourable Standish Vereker in this film. This character did exist and was an officer with the NNC and perished in the flight from the battlefield.

As the reader can appreciate in an action like Isandlwana, many men have small but important parts in the action. In a film, to create all these characters for a fleeting moment only serves to confuse the audience. To simplify it all and make things work, Vereker plays the part of a number of men on that fateful day and becomes a major character in the story. This part is played by Simon Ward. In the film Vereker’s role incorporates the actions of Vereker himself, Captain Bradstreet, George Shepstone and, finally, at Fugitive’s Drift, Lieutenant Higginson.

This sequence is not historically accurate either, as the Queen’s Colour is not washed out of Lieutenant Melvill’s hand, but is dropped in the river by a fleeing Zulu after Vereker shoots him. This ending is more theatrical and the Director rewrote it this way. He doesn’t let Melvill and Coghill get far from the river bank either.

I did not see this sequence being shot, which was done at the real Fugitive’s Drift. I had earlier taken a film crew, complete with two horses and riders, to prove the feasibility of using this drift again. To my surprise the water, even in mid-winter, was too deep for horses to cross without swimming.

Horses swimming across Fugitive's Drift

With a production of this size there are many little facets that cannot be recorded here, but for me it was an unforgettable experience.

If you would like an unforgettable experience join us on the Fugitive's Drift Walk 3-5 September 2021. Click here to for all the details.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.