The airline industry came of age in 1957 when for the first time more passengers crossed the North Atlantic by air than by sea. The jet aircraft—with its capacity to move hundreds of passengers within twenty-four hours from the southern tip of Africa to any major European city—sounded the death knell for the ocean-going passenger liner as the primary means of long-distance travel. Air travel was still a luxury, however, and sea travel retained its appeal. A Union-Castle mail ship voyage from Cape Town to Southampton took eleven days, cost perhaps as little as £140 sterling, and offered the prospect of shipboard friendships—or romances—unfolding at an unhurried pace. But the tides of transport were already turning.

My own memories sharpen the resonance of this book. In 1963 I flew to New York, a green eighteen-year-old on an American Field Service scholarship, when group package tickets had begun to democratise air travel. Yet in 1968 my journey to the United Kingdom was from Durban aboard the Windsor Castle, travelling tourist class. It was an experience of a lifetime. I had just resigned my first professional post as an assistant economist, and one of my earliest published articles examined the coming revolution in cargo handling through containerisation—though at the time I scarcely grasped how profound that revolution would be. Turning the pages of Halcyon Days brought all these memories vividly back.

Model of the Windsor Castle (Wikipedia)

This handsome volume is, at heart, a nostalgic pictorial celebration. It presents Nigel Hughes’s personal selection of more than eighty full-page colour photographs—many originating as colour slides—of passenger liners operating in the 1940s and 1950s. The emphasis is on exterior views: majestic vessels photographed at anchor or alongside quays, poised between departure and arrival. The book’s clear and effective format places a full-page image on the right-hand page, with a concise but information-rich text on the left summarising the ship’s vital statistics, ownership, service history, and eventual fate.

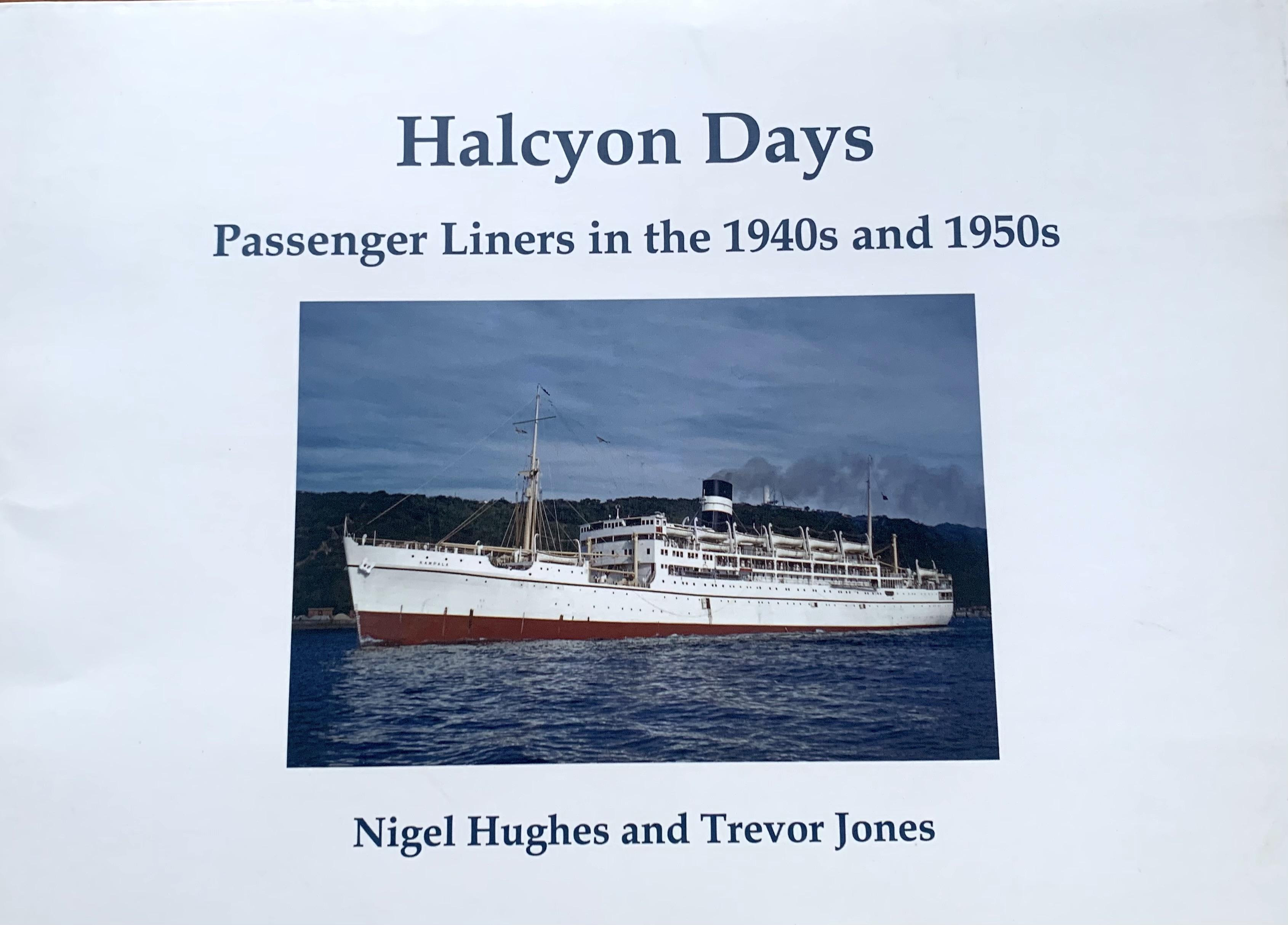

Book Cover

Each ship’s story follows a familiar arc: conception and construction, periods of service—often under changing flags or ownership—adaptation to new markets or passenger classes, and, finally, breaking up and scrapping. Hughes and Jones write with fluency and authority about shipping terminology and maritime practice. Their research is impressive, underpinned by a substantial bibliography that testifies to the care taken with technical accuracy and historical detail. Dramatic episodes—wartime service, collisions, fires, or other mishaps—are recounted succinctly and without sensationalism.

What the book largely foregoes are personal narratives: the voices of captains, crew, or passengers whose lives unfolded aboard these ships. This is a deliberate editorial choice rather than a shortcoming. The focus remains squarely on the vessels themselves as artefacts of design, engineering, and economic history—icons of an era when maritime travel still shaped global mobility.

Today’s passenger ships, by contrast, are floating cities conveying thousands of holidaymakers on tightly scheduled cruises to Mediterranean ports and beyond. As my daughter wryly observed after a recent Greek island trip: if you truly want to enjoy the islands, take ferries to places without cruise-ship ports. In that sense, Halcyon Days offers the superior alternative—armchair travel at its most evocative—allowing readers to savour a vanished world of measured pace, elegance, and anticipation.

The book’s concluding reflections situate these liners within a wider historical transformation. Britain no longer commands an empire or rules the seas; international shipping has become a fiercely competitive, globalised industry; and container ships now dominate the movement of goods. Against this backdrop, the great passenger liners appear as the graceful casualties of progress.

The cover photographs are especially striking. The back cover shows Cunard’s Aquitania and Queen Mary, alongside Compagnie Générale Transatlantique’s Normandie and Île-de-France, moored at their Manhattan piers in 1939, photographed from an airship. This single image captures the zenith of an era. At a local Johannesburg level, the Normandie even left its imprint on the city’s built environment: the ship lent its name both to a Houghton home built by a newly married couple who honeymooned aboard her, and to Normandie Court, a 1937 apartment block designed by Grinker and Skelly for the developer Shim Lakofski.

Back Cover Photograph

Halcyon Days is a high-quality production by authors who are passionate, knowledgeable, and generous in sharing a remarkable photographic archive. It is a book that fascinates, educates, and entices the reader to dream—of ocean crossings, distant harbours, and a world when travel itself was an event. Truly, these were halcyon days.

Purchase your copy from Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. 060 813 3239

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also a previous Chairperson of HASA.