Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Saldanha Bay, with its perfect setting for a harbour, was always constrained by the lack of fresh water. With the Khoekhoe's transhumant existence, the Vredenburg Peninsula formed part of seasonal grazing, which was dictated by the seasons, with summer providing little rainfall and winter being the opportunity to graze cattle and sheep. The early seafarers and explorers who entered the safe haven found that the lack of a permanent fresh water source restricted any concept of settlement.

When a ship, the Pearl, captained by an Englishman Samuel Castleton entered Saldanha Bay in 1612, he was able to trade a calf and sheep for an iron hoop and hatchet with the Khoekhoe based there. They advised him that besides a small ‘puddle’ there was no other water in the vicinity. He declared it a ‘very barren place’.

Subsequent explorations by the Dutch, French and British all reached the same conclusion: a fine, placid natural harbour, but devoid of an adequate water source. The British author, John Barrow, saw the bay as a ’spacious, secure, and commodious sheet of inland sea water, for the reception of shipping, hardly equalled in any other part of the world’. He reported two brackish springs near Hoedjes Bay and went on to suggest laying a course to a farm, Witteklip, 10km north to create a supply; not a new idea as it had been proposed previously in 1738. This would have been prohibitively expensive.

He then had the idea to tap into the Berg River, which became a concept discussed with the the Dutch officials, including Col Robert Gordon. Barrow had a vision for Saldanha Bay to become a strategic military port, and a trade and industry harbour.

The geology of the area is defined by underlying granite, which appears as hills and domes, and overlaid by sandy soil of varying depths. This configuration allows the sparse rain to soak in or evaporate quickly, with little surface water left.

The situation was to change dramatically during World War II when the Union Government made the decision to tap the waters of the Berg River. Some water had been found by then near Langebaan, by digging wells, but to the north it was obtained by harvesting rainwater and storing in underground tanks. The poorer residents, the ’coloured’ fishing community, did not have access to these faculties and the South African Railways (SAR) were utilised to haul fresh water from Kalbaskraal in the Swartland.

Kalbaskraal Station, a contemporary view, in a neglected state.

A number of proposals had been discussed during the period between the two wars, with private profit seemingly part of the motivations. One came from Martin Melck of Kersefontein, to construct a weir across the Berg River upstream from the mouth, to eliminate the influx of sea water during the reduced summer flow. If situated near the farm it could possibly have benefitted financially from the operation. None of the projects came to fruition, however.

As a result of the decision to utilise Saldanha Bay as a naval port during World War II the population increased, putting further pressure on the totally inadequate supply. A scheme to ship water from Oostewal to Saldahna did not solve the problem.

In June 1942 the Union Government granted permission to lay a 55 kilometre pipeline from the Berg River to Saldanhna Bay, and a site was selected on the farm Jantjesfontein, and a section, including a large five-bedroomed house and outbuildings, was purchased. It was acquired from brothers Martin and Arthur Melck, for the erection of a pumping plant and purification works, and servitude for the pipe.

The barn, assumed to be one of the outbuildings mentioned in the farm sale; the structure alongside is of a later type.

Detail of the barn

One of the benefits of the selected site was its proximity to a rail station, that of Bergrivier, which facilitated the delivery of heavy piping, supplies and equipment for the construction.

Bergrivier Station, still in use for commercial traffic

Two military companies comprising nine officers and 106 men were on site by mid 1942, joined by an initial force of 172 African* workers, an insufficient number for the project, rising to 729 late in the year.

Two views of the elongated structures, presumably barracks used by the military. There is no indication of where the army would have housed their personnel and the labour force.

The interior of one of barracks, with the later additions of cattle pens.

The course of the pipeline from the waterworks was surveyed and pegged by engineers, with camps being established at numerous points along the route. Work began immediately on the excavations, construction of the waterworks and storage reservoirs, and laying of the pipes. The latter process was often challenging as anyone who is familiar with the Sandveld will be aware - the sand is mostly soft and difficult to dig.

Photograph from the 1938 aerial survey, showing the location of the waterworks, and also Bergrivier Station to the north.

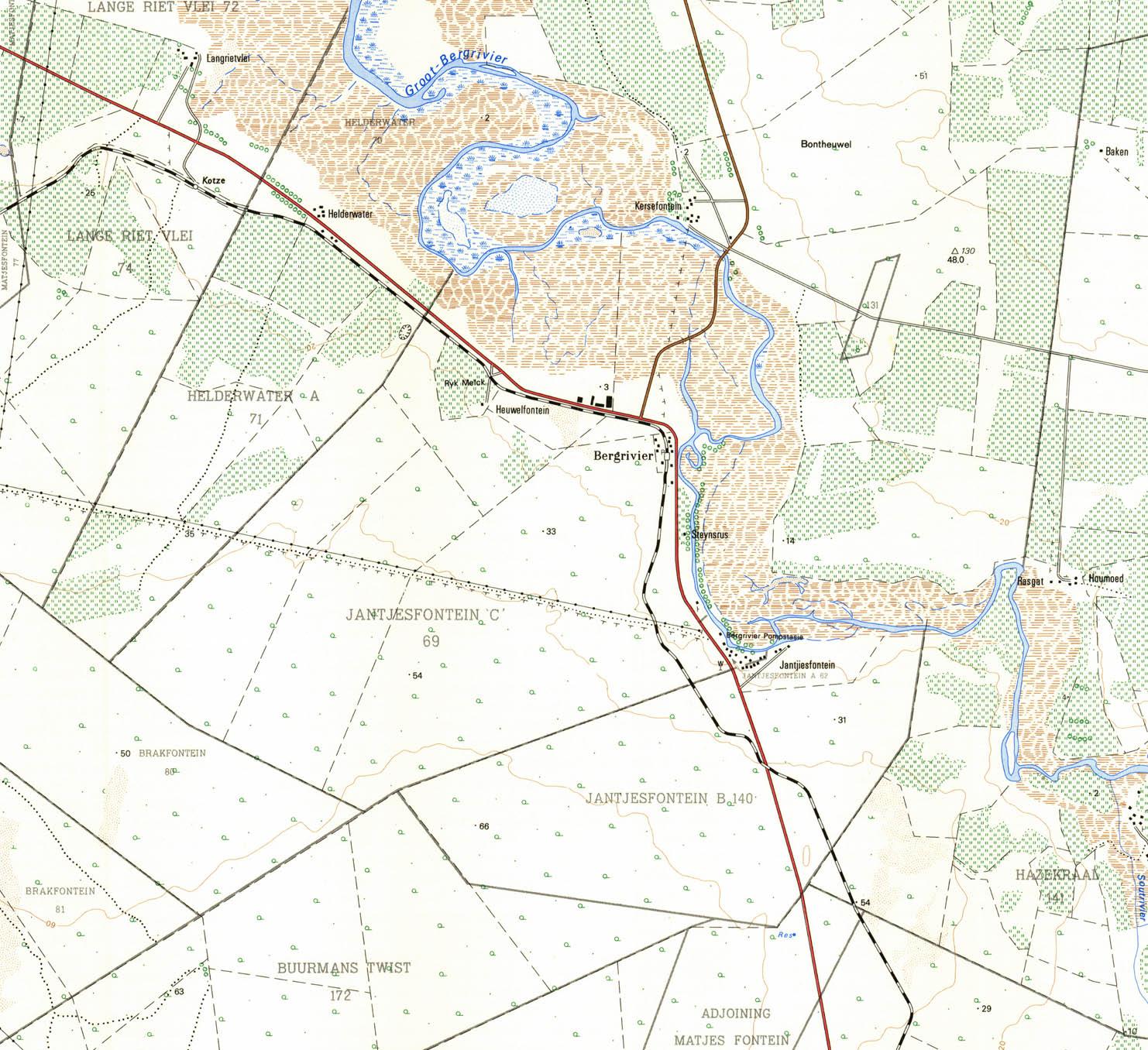

Mapping & Surveys map, with the ‘pompstasie’ indicated; it still shows the route of the water pipe leading in a north westerly direction.

The storage dams, now empty

A covered water tank.

A tower on site, the usage of which is not determined.

One of the lamps that stand over each of the dams.

A section of the water pipe.

Pressure also came from the fact that German submarine activity off the coast had increased and the necessity to afford protection was a priority. To this end other non-essential activity was ordered to be ceased, with the intention of speeding up the construction of the pipeline. The first water reached Saldanha Bay on 7 February 1943, alleviating the previous shortages.

Today the waterworks, now obsolete, stand semi-derelict on the banks of the Berg River. Some of the houses are still occupied whilst others appear deserted.

Two of the houses at the site, presumably abandoned

*Much as I am disinclined to make racial distinctions, it is an important part of this story, in that racialism was enshrined in the South African Defence Act of 1912, only permitting people of colour to perform inferior rôles. This appalling situation, as we know, took until 1994 to rectify.

Reference: This article heavily relies on a publication: Water for Saldanha: War as an Agent of Change by Deon Visser, André Jacobs and Hennie Smit, published in Historia 53.1, May 2008.

About the author: Chris was a member and subsequent chair of the Swartland Heritage Foundation for many years. He has also completed the Urban and Architectural Conservation course at UCT. At present he is the chair of the West Coast Museum Forum.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.