Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Perhaps you recall the 1980s advert, ‘Where did you have your first Campari? – in Benoni.’ That was well before Charlize Theron made Benoni famous.

Well, you do not have to be a taphophile (someone who takes an interest in cemeteries and tombstones) or require a taste for Campari to visit the Rynsoord Benoni Cemetery.

If you are interested in the 1913 Mineworkers Strike, the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic, the 1922 Rand Revolt, the Crimean War or even the Mapungubwe Heritage Site, then the Rynsoord Cemetery is for you.

This Cemetery, on Main Reef Road (R29) is still active, but its oldest precincts contain many interesting and historical graves, all relating to the above events.

When you enter the cemetery driveway, travel towards the cemetery offices where the lych-gate is situated (main image). The lych-gate built in the Arts and Craft style is worthy of preservation. The lower walls are of dressed stone and the internal wooden trusses are most attractive. Originally, this structure probably served as a covered area to the burial ground where the coffin would have been placed on a pedestal prior to the burial service.

The older precincts (Wesleyan, English & Methodist and Dutch Reformed Sections 1 & 2) are situated west and south west of the lych-gate.

In the Wesleyan precinct, next to the covered parking lot for cemetery staff, is the grave of the very first internment in this cemetery, namely that of Norew Sunney, a Marine Engineer formerly of Doncaster England, who died on 17 October 1911. At the base of his grave is a memorial stone which reads, ‘This memorial was erected by the Town Council of the Municipality of Benoni to further commemorate the first internment in this Cemetery’.

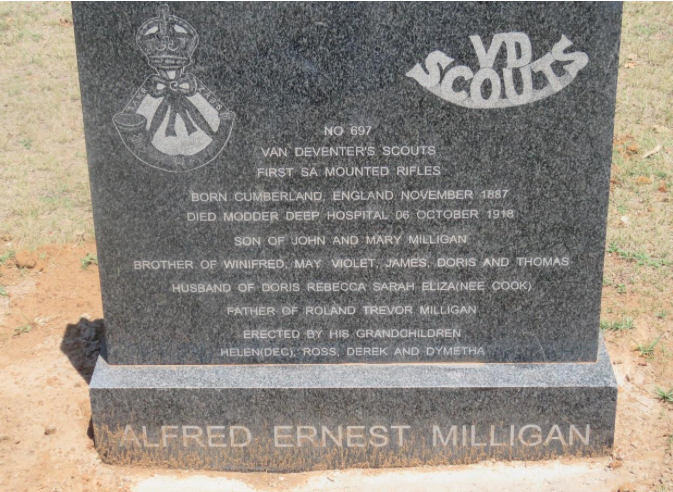

Nearby is an interesting and recently erected tombstone to Alfred Ernest Milligan. His epitaph states he was No. 697 of Van Deventer’s Scouts and 1st SA Mounted Rifles. Born November 1887 and died Modder Deep Hospital on 6 October 1918. Many of the returning soldiers who fought in East Africa suffered from malaria and other tropical diseases. Due to a weakened constitution he may well have fallen victim to the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic.

Grave of Alfred Ernest Milligan (SJ de Klerk)

There is also a tombstone to Thomas Smyth Kerr, who most likely also died from the Spanish Influenza. His epitaph reads, ‘Late County Antrim, Ireland. Died on 27th October 1918, Aged 27 Years’.

Towards the end of September 1918, the 2nd wave of the world-wide Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 struck South Africa. Spreading at the speed of a steam locomotive, this country was overwhelmed within a space of two weeks by the worst natural disaster in its history.

The pandemic is thought to have originated in Asia late in 1917 or early 1918, then moved westwards and appeared in a mild form in Europe and North America in the first half of 1918. It was this 1st wave which produced the label ‘Spanish’ Influenza, as reports of its outbreak in non-belligerent Spain were not limited by any war-time censorship there. Howard Phillips argues the 2nd more virulent wave erupted in August 1918 and was rapidly conveyed around the world from three main sea ports, Brest, Boston and Freetown. It was most likely from Freetown that the deadly 2nd wave was brought to Cape Town in mid-September by returning soldiers of the SA Native Labour Contingent. Durban was infected slightly earlier, probably by the much milder 1st wave of the epidemic. By the time the 2nd wave abated in November 1918, between 250 000 and 300 000 South Africans may have died, although many fatalities in rural areas went unrecorded. Locally, this disaster was afterwards known as the ‘Black October’. It is an interesting phenomenon of this pandemic that people in the age group 15 to 45 years were the most susceptible to it.

In Benoni an estimated 505 people died out of the town’s total population of 42 275, a mortality rate of 11.9 deaths per 1000 people. In Springs/Boksburg, which was then measured as one area, the mortality rate was slightly lower with 430 deaths out of a total population 56 190, a mortality rate of 7.6 per 1000 people.

Globally, it is estimated that the Spanish Influenza pandemic killed approximately 20 million people, making it the worst pandemic in modern times.

Van Deventer’s Scouts was part of the 1st Mounted Brigade and served during World War 1 in German East Africa, then also called Tanganyika and today Tanzania.

As may be expected in what was then a predominantly mining district, there are numerous tombstones of people killed in mining accidents or who died in mine hospitals, scattered across all the cemetery precincts. Only a few of such tombstones will be highlighted.

In the Wesleyan precinct there is a tombstone to William Thomas Gray accidentally killed at New Kleinfontein Gold Mine on 31 March 1923. Aged 34 years.

In Section 1 of the Dutch Reformed precinct, are tombstones of nine miners all grouped together, part of a larger group of twelve, who were all killed in an accident at the Brakpan Mine on 8 December 1916. The nine whose tombstones are in this precinct include Marthinus van Rooyen Kapp, John Henry Oosthuizen, William Henry Collins, Petrus Albertus Pepler, Frans Johannes van Aardt Jansen van Rensburg, Christoffel J. Campher, F. W. M. Swanepoel, Cornelius J. D. Small and Cornelius Raath.

There is also a poignant tombstone in early Afrikaans, ‘Rusplaats van mijn dierbare zeun George Henry Gravett. Geboren 2de Mei 1892. Verongeluk in de Brakpan Mijn de 24ste Januarie 1920.’

Nearby is a sad tombstone to Johan Christian Scheepers killed in a mine accident on 21 November 1921, and his son Frederick Johannes Scheepers killed in an air crash with the SAAF on 10 September 1942.

These and other similar tombstones serve as reminders that the profits of the gold mining industry were achieved at the cost of many lives. Statistics quoted by H. Wagner, which were compiled from government sources, indicate that 2 962 White employees and 41 143 Non-White employees died from accidents on the Gold and Uranium Mines in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State from 1911 to 1982, inclusive. This averaged 41 White employees and 575 Non White employees per annum over the seventy two year period. These statistics do not include vast numbers of mine workers who died because of mining related illnesses and diseases.

Almost all graves you are likely to see in the older cemeteries of Johannesburg and on the East and West Rand, which are associated with the mining industry, are those of White mine workers. Most African mine workers lie buried in forgotten graves either at some long closed down gold mine or at a rural African village somewhere in Mozambique, Lesotho, Swaziland, Malawi, KwaZulu-Natal or Eastern Cape. The large number of mine fatalities presents an alternative perspective as to why both the 1913 Strike and the 1922 Rand Revolt were characterized by so much violence. Mine workers perceived that the mine owners viewed them as mere assets to be used and discarded when no longer required and when unable to work because of silicosis or other industry related illnesses.

The East Rand Gold Mines were among the last to be developed along the Main Reef, which at that time was considered to stretch from Nigel or thereabouts, to Randfontein. The government owned large tracts of land in the East Rand and it offered mining companies the opportunity to lease such government owned land. Under this system, mining companies could tender for a lease and operate a mine on the proviso that part of the profits would be paid to government. In effect, government became a partner to the mining companies, accruing profits without actually having to invest or contribute to the operation of the mine. Not surprisingly, many of the mining companies balked at this arrangement. It was under these conditions that the Johannesburg Investment Company floated the ‘first’ leased mine, Government Gold Mining Areas (Modderfontein) Consolidated Limited in 1910. The success of this mine established the leasing system and other mines soon followed suit – Brakpan, Daggafontein, East Geduld, Modder East and so on. By the 1950s there were 22 large mines operating on the East Rand.

In the adjacent English and Methodist precinct there are eight graves of members of the Special Mine Guard, South African Police and Transvaal Scottish Regiment respectively, who were killed during the 1922 Rand Revolt at Benoni and Brakpan. Most of the fatalities occurred between 10 and 12 March 1922, when the Revolt was at its height and for a while it seemed that the strikers might prevail. However, by 14 March, the government forces had largely suppressed the Revolt.

There are two tombstones for the members of the Special Mine Guard who died while attempting to safeguard the mines during the strike.

The first one is an attractive white marble tombstone mounted with a cross and a superimposed rifle. The epitaph reads, ’In loving memory of my husband Dennis Higgins who met his death at Van Ryn Estates 10th March 1922. Aged 41 years. He saved others. Himself he could not save’.

Next to it is an imposing black granite tombstone to Horace William Adcock who was also killed on 10 March 1922.

Dennis Higgins and H. W. Adcock (SJ de Klerk)

There are four similar black granite tombstones to Constables Frederick Henry Ludwig Howe (killed 10 March), N. A. C. Kruger (killed 10 March), Benjamin Hannant (killed 10 March) and Sergeant F. W. Hooper (killed 12 March), which were erected by the South African Police. There is a white marble tombstone, which has unfortunately broken into two pieces and lies flat on the ground, ‘In loving memory of Constable Addison Ridley Jordan. Beloved son of C. E. and W. Jordan. Born February 5th 1900. Died March 10th 1922. Aged 20 years.’

There is also a black granite tombstone to Sergeant H. H. Roux of the Transvaal Scottish Regiment. This tombstone was erected by the Regiment in 1970.

160 Men of the Transvaal Scottish Regiment were sent on 10 March 1922 to support the beleaguered Police in Benoni. A hefty skirmish broke out with an opposing striker commando at the Dunswart railway crossing, where 3 officers and 9 troopers were killed. Sergeant Roux’s tombstone only provides the month of death, but he was most likely also killed at Dunswart.

On the eve of the Rand Revolt there were approximately 200 000 workers on the gold mines of which Whites constituted about 20 000. The Revolt commenced in January 1922 when White workers from the gold mines, engineering firms and power stations went out on strike. The origins of both the 1913 and 1922 strikes are broadly similar, and mainly due to attempts by the Transvaal Chamber of Mines to reduce both the work performed, and pay earned, by higher paid White miners, while increasing the work performed by lower paid African mine workers, so as to reduce operating costs of the mines. Who can forget the infamous slogan of the white strikers from the 1922 Rand Revolt, ‘Workers of the World Unite and Fight for a White South Africa’?

Chamber of Mines Building in Marshallstown (The Heritage Portal)

Ivan L. Walker and Ben Weinbren quote the Report of the Martial Law Inquiry Judicial Commission, that 153 people were killed or died of wounds during the Rand Revolt, as follows:

- Armed Forces - 43;

- Police - 29;

- Revolutionaries - 11;

- Suspected Revolutionaries - 28;

- Innocent Civilians - 42.

Nearby the graves of the 1922 Rand Revolt is a tombstone which reads, ‘In Loving Memory of Frederick Karl von Mengershausen. Late Professor of Mining and Surveying Johannesburg University College. Died at New Modder December 27th 1920 aged 39. Son of the Late Dr. Von Mengershausen of Howick, At Rest.’

The School of Mines was originally established in Kimberley in 1899 as a technical training school for the mining industry. In 1904 it was moved to the Johannesburg CBD to meet the local demand for the training of engineers and technicians for the gold mining industry. The Johannesburg School of Mines is therefore the precursor of Wits University.

Old School of Mines Building in Kimberley looking worse for wear (David Morris)

Great Hall at Wits University (The Heritage Portal)

In the same precinct, but slightly to the north-west, is the historical tombstone of Thomas John Gifford Lane (4 September 1831 to 19 December 1913) whose epitaph states he went through the Crimean War under Commissariat Generals Fielder Adams and Sir William Drake. His tombstone is an unusual and attractive one of white marble, mounted with a cross and a superimposed sword in a scabbard.

Grave of T. J. G. Lane (SJ de Klerk)

The origins of the Crimean War lay in a dispute between Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests in 1850 as to who had ‘the right of first access to certain holy Christian places’ in the Ottoman-controlled holy cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

Tsar Nicholas I wanted recognition from the Ottoman Sultan for what he felt was his right to represent and protect Christians in the Ottoman Empire.

In reality, the war came about because of the Russian desire to gain access to the Mediterranean through the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, an area controlled by the Ottoman Empire.

It is also not generally remembered today, that one of the former Cape Governors, Sir George Cathcart, died at the Battle of Inkerman on the Crimea, while leading his brigade into battle on 5 November 1854.

Next to T. J. G. Lane’s grave is the tombstone of Arthur Edward Morgan of the 1st Regiment SA Mounted Rifles who died on strike duty at Benoni on 13 July 1913.

The 1913 Mine Workers strike is now almost forgotten and overshadowed by the 1922 Rand Revolt, but the causes of the two strikes were quite similar.

Lastly, for something quite different.

In Section 12 of the Dutch Reformed precinct, lies the interesting grave of Jerry van Graan (1908 to 1987). His grave is covered by a large engraving of the well-known golden rhinoceros of Mapungubwe and the inscription ‘Ontdekker van Mapungubwe’ (Discoverer of Mapungubwe).

Van Graan was one of a small party who ascended the purportedly mystical Mapungubwe Hill in 1933, having heard rumours of gold and treasure buried there. Gold artifacts were excavated and divided amongst themselves. Van Graan, being a university student had second thoughts and subsequently informed Professor Leo Fouché from the Department of History at the University of Pretoria, of their discovery. The University of Pretoria became involved with this site and proceeded with the longest Iron Age archaeological excavation project ever undertaken in Southern Africa.

Grave of Jerry van Graan (SJ de Klerk)

Mapungubwe was declared a World Heritage Site in 2003.

Post script. The Rynsoord Cemetery is well maintained and safe to visit during working hours on weekdays when the cemetery employees are present. Care should however be taken when visiting the cemetery during the weekend, especially at the older precincts where visitors are less prevalent.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South Africa's historical cemeteries.

Sources:

- Antrobus E. S. A. (Editor). 1986. Witwatersrand Gold – 100 Years: A review of the discovery and development of the Witwatersrand Goldfield as seen from the geological viewpoint. The Geological Society of South Africa.

- Davenport J. 2013. Digging Deep: A History of Mining in South Africa. Jonathan Ball Publishers.

- Figes O. 2010. The Crimean War: A History. Metropolitan Books.

- Krikler J. 1995. The Rand Revolt: The 1922 Insurrection and Racial Killing in South Africa. Jonathan Ball Publishers.

- Oberholzer A. G. 1982. Die Mynwerkingstaking Witwatersrand, 1922. Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria.

- Phillips H. 1990. “Black October”: the Impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa. Archives Year Book 1990 (1). The Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Stevens M. 2000. Civilians at War: William Henry Drake and the Commissariat at War. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts at Monash University.

- Tiley-Nel S. 2004, Mapungubwe: South Africa’s Crown Jewels. Sunbird Publishing.

- Van der Waal G. M. 1987. From Mining Camp to Metropolis: The buildings of Johannesburg 1886 – 1940. Chris van Rensburg Publications.

- Wagner H. July 1988. Discussion: Safety on South African Mines – Contribution by H. Wagner. Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy.

- Walker I. L. & Weinbren B. 1961. 2000 Casualties: A History of the Trade Unions and the Labour Movement in the Union of South Africa. The South African Trade Union Council.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.