Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Until the middle of the 19th century, few authorities worldwide bothered about safety at sea and more particularly about the provision of lighthouses. The sea was a demanding mistress and was entitled to claim vessels, cargoes and lives, and the ruling classes who governed nations and held the purse strings were unaffected and unconcerned by losses at sea. And so the wrecks piled up on the treacherous coasts of Europe and North America, and in some numbers on the uncharted peninsulas and capes around the southern tip of Africa.

Photographing a shipwreck at Cape Point (SAHRA)

Certainly the Dutch East India Company was not prepared to spend its profits on maritime safety around the Cape of Good Hope, and left any efforts in this respect to the initiative of the Governors – to be funded from the normal budget. Van Riebeeck had a go at putting a bonfire on Robben Island, but soon gave up when the local supplies of wood were exhausted. Thereafter the Dutch did nothing.

At the time of the British takeover of the Cape, the authorities in Whitehall and their parliamentary masters were still indifferent to the funding of lighthouses from the public purse. The shipowners, the citizens of the Cape, the merchants there and in India began to agitate for proper facilities but their petitions fell on deaf ears. The government simply denied that it was its responsibility to finance such facilities – they reasoned that “if those at the Cape wanted lighthouses they should pay for them themselves” - and as the Cape had no funds of its own there was no progress.

One of the first to make his voice heard was Admiral Sir Jahleel Brenton, during his term of duty at Simon's Town between 1815 and 1821. Just before his arrival the troop ship “Ärniston” had been wrecked in Struis Bay with the loss of 372 lives and had raised a huge outcry. He estimated that during his incumbency the cost of losses in Table Bay alone amounted to £3,400,000. But the British Government was unimpressed. Lights used purely for local purposes had to be operated and maintained from the local purse - which, for the impoverished and neglected Cape Colony, was usually empty.

Sir Jahleel was an unusual and colourful character – an American who had risen to flag rank in the British Navy. His major work here was to survey and map the coast from Cape Point to Algoa Bay, during which he was one of the first to negotiate a proper ocean-going ship through the Knysna Heads. The nearby resort of Brenton-on-Sea is our lasting reminder of a competent and principled officer.

Portrait of Sir Jahleel Brenton (National Maritime Museum)

Sir Rufane Donkin, who acted as Governor between 1820 and 1821, had other ideas about the value of lighthouses and pushed ahead with plans for a light at Green Point. He called for tenders without proper authority and awarded a contract for 13400 rix-dollars to Herman Schutte. However, Governor Lord Charles Somerset returned before the job got under way and he put the project on hold. There was a delay of some three years before permission was granted to proceed. Eventually, after Admiral Brenton convinced Somerset that the lighthouse would be of enormous value to merchant shipping, funds were authorised and the job went ahead.

Schutte is the least well known of the triumvirate who had a huge influence on the appearance of 19th century Cape Town – the other two being Louis Thibault and Anton Anreith.

He was born in Bremen and trained as a stonemason and an architect, which in those times must have included the then current knowledge about the theory of structures. After practising in Hanover for seven years he arrived at the Cape in 1790. Soon afterwards he became involved in a brawl and was banished to Robben Island where he lost an eye and a hand in a blasting accident. After serving his time, he returned to the mainland, where, disabled and unable to ply his trade, he set up as an architect and builder. Thibault helped him get established by giving him work on repairs to the Castle. His practice grew, and he became involved in the design and construction of the Good Hope Lodge (he was a confirmed Freemason). He then was commissioned to build the original St Georges Cathedral – and lost heavily on the deal. His most important work, the Groote Kerk, was both designed and built by him, and was completed in 1841.

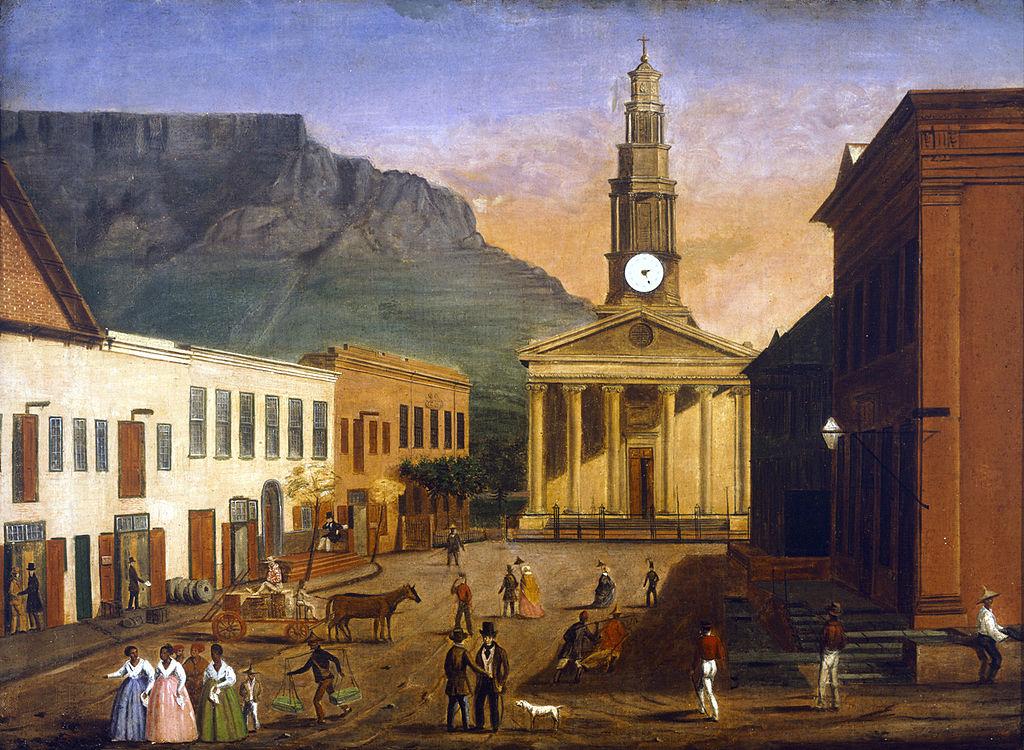

Old painting of the first St George's Cathedral

Groote Kerk

After Thibault's death he took over as the Inspector of Government Buildings, and later became the Town Surveyor for the new Municipality of Cape Town.

Where and how he learned about lighthouse design is not known, but he produced a practical structure in which the light was displayed for the first time in April 1824. Originally the Green Point light had two lanterns: these were converted into a single, more modern appliance some years later. The design has stood the test of time, and despite many modifications the original building is still recognisable and in use today, and now also houses the headquarters of the SA Lighthouse service.

Apparently Schutte habitually underpriced his contracts and was invariably short of cash; although his Masonic brethren assisted him, he died in poverty in 1845. His gravestone is in the Groote Kerk.

The Governor’s purse apparently did not extend to funds for maintenance and by 1828 the Green Point light had fallen into disrepair. Major Charles Michell repaired it and restored it to working order. The campaign for lighthouses continued until the British Government came round to accepting that marine safety was the responsibility of the state, and from 1847 lights began to appear at all critical points on the South African coast.

Main image: Green Point Lighthouse via SJ de Klerk

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.