Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

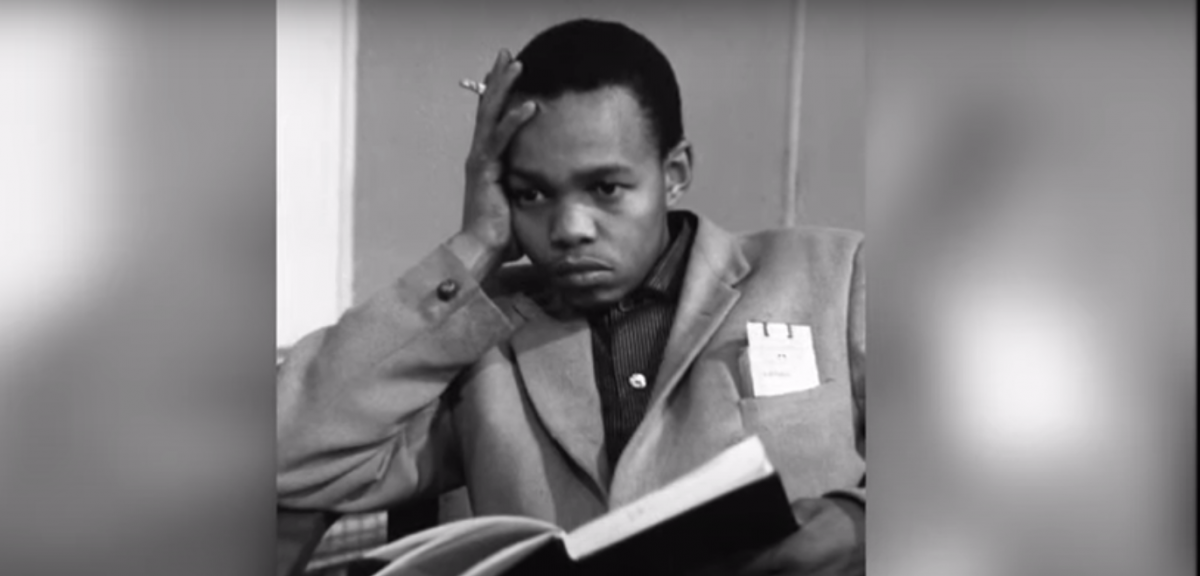

July is mid-summer and warm in New York. But in this world city, July 1965, Nat felt cold, miserable, depressed and missing his country, his people.

Nataniël Nakzana Nakasa, popularly known as Nat, could not ever return to his country of birth. The premier placing this restriction on his passport which prevented him from returning to South Africa, was none other than the architect of apartheid, Dr Verwoerd. Verwoerd, as Nat once commented, was himself not even born in South Africa (Dutch), while Nat was.

Verwoerd (via Wikipedia)

Nakasa left his country from Johannesburg in 1964 to follow his dream. It was an ideal of many journalists, to study at Harvard. He persevered and became a Nieman Fellow in 1965 – maybe the first South African who accomplished this fellowship. Eventually he moved to New York to practice his skill with vigour.

In New York that summer, Nat was depressed. He had experienced an America riddled with racism, albeit more subtle and not as legislated like in his home country. Maybe this also contributed to his lesser success in selling articles. Yet, he appeared on television, a programme on apartheid: The fruit of fear.

Nat also surely missed his people in Durban in Natal, now KZN. That is where he grew up and where his father, a letter setter, his teacher mother and his 4 siblings, lived. And there he started writing articles even before he completed Standard 8 (Grade 10) in Estcourt, a Natal district. He left school and seriously worked on his career as journalist – Zulu for Illanga and English for other papers like Golden City Post.

It was inevitable for him to move to Johannesburg, then the mecca of South Africa’s black journalists, as assistant editor at Drum. He was just 22 at the time. Gradually he also freelanced at the then popular Rand Daily Mail.

Study at Harvard may have became a reality after his coverage of the Sharpville Massacre. In 1961 the New York Times published his article: 'The human life meaning of Apartheid’. He then successfully applied for acceptance as a student at Harvard.

Surprisingly the apartheid government did issue a passport, but as mentioned and not surprising, with the major condition of no return. Unknown to him he had been under the eye of security police for 3 to 4 years.

At that time Nat had already launched the magazine Classic and as editor, intended to encourage the publication to be a fight for just causes. Nat Nakasa was the young successful, controversial, satirical, bright journalist with ambition and a promising future in a career not popular with the authorities at the time.

Life in Johannesburg was a challenge since he, Nat the journalist, had no address.

In an article, Johannesburg, Johannesburg, he described how he spent the first 8 months in this city. After all, he was most probably illegal in terms of the then Influx Control Regulations. If he was in the city on permit, as required for a Black person visiting a region other than what his pass book determined, movement in town was at a risk. Being in town after 10pm was a risk. This strict rule dated back to 1923 – no black person was allowed on the streets after that hour.

The Albert Street Pass Office in the Johannesburg CBD (The Heritage Portal)

Permits were issued in compliance with legislation adopted in line with the Group Areas Act of 1950, which contained more restrictions in addition to the existing restrictions of the Urban Areas Consolidation Act (25/1945). Furthermore, hostels in townships were developed for employees working on permit in Johannesburg (Soweto’s vigorous hostel schemes took off as from 1956).

Nakasa, related in Johannesburg, Johannesburg, how he, posing as a Mr Brokenshaw with a fake Oxford accent, called a hostel superintendent. He enquired about an available bed, receiving the reply that there was indeed an available bed in one of the 10/12 bed dormitories: 'But I must explain to you we are only taking special boys now'.

Those special boys as the sup explained, had to be employed in essential services like milk delivery, sanitary services!

Obviously, a journalist would not qualify as rendering an essential service, but Mr Brokenshaw was not really interested in a bed for his employee. His call was part of research.

The homeless, dedicated researcher Nat Nakasa, was happy to be allowed to use the library at Wits University. At Wits he befriended white liberals. He was successful in his career, in spite of having had to squat somewhere every night. Squatting included staying overnight in the room of a night watchman of a building in downtown. (Cleaning and security staff at the time were accommodated in roof top flat and office complexes – so-called locations in the sky – belonging to their employers. Eventually all of them were forced to move into township hostels).

William Cullen Library at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

Nat described how at Wits he also became friends with a liberal Afrikaans painter. On enquiry the painter was surprised to learn about Nat’s lack of accommodation. He offered him a room to stay at his home in the white suburb (perhaps it was no backyard boy’s room, but not to be judged since that was a friendly gesture and an outcome – better than the hostel or having to look for a place or invitation every night as homeless journalist).

Yet, the enlightened host-to-be stated that he remained a supporter of Verwoerd and the then Nationalist Party, because that is how it should be for him, the painter.

This forces us to borrow from a book title by a recently deceased Afrikaans writer Jeanne Goosen, ‘Ons is nie almal so nie’ (we are not all like that).

A good example, was the narrative of a journey by the dedicated journalist Dana Snyman (then with Huisgenoot). In the article he published afterwards, he narrated the full journey he embarked on to find the grave of his icon Nat Nakasa. And seeking closure. This search: a formidable challenge in New York, but testimony to perseverance and determination.

To start with: imagine how many graveyards there are in this major city and surroundings? And scattered. But with dedication Dana managed to find a lead and caught a train to the Ferncliff Cemetery, Hartsdale. This seemed to be where most black people who died in the NY environment, were buried. On the train a chatty fellow passenger found it strange, this mission. However, not strange to Dana.

What he found at Hartsdale, was an enormous cemetery – an endless panorama of graves with no headstones, only identifying information on copperplates. Chuck, working at the cemetery, was surprised that he was not looking for the grave of Malcolm X like many other pilgrims. Yet he traced Nat’s grave number by checking endless papers. Carrying a map, Chuck and Dana’s search began to find the grave of Nat Nakasa who died on 14 July 1965 and was buried in this cemetery.

Nat’s death followed two days after he told a friend: I cannot laugh anymore, and when I cannot laugh, I cannot write. The very Malcolm X with whom he ultimately shared a cemetery, led his funeral service, while Miriam Makeba – whose biography Nat so much wanted to write – sang his farewell. There may have been other exiles present, perhaps American friends, but no family, therefore surely lacking traditions as required to secure his ancestral passage.

There was no choice: Nat Nakasa, accomplished graduate and journalist, stateless in a foreign country, had to be buried far from home, the funeral lacking the presence of family and important Nguni rituals to facilitate the ancestral journey. He was only 28 years old.

Dana and Chuck almost missed Nat’s grave, then also covered with grass. But no name plaque – only a tag with the number: 1302.

Here Nat was buried when depression and all of the reality he faced, became unbearable. On 14 July 1965 he opened the window of a friend’s apartment on the 7th floor in New York. He jumped.

Resulting from the translation into English of Dana Snyman’s 1993 article, Nat’s grave received at least some identity since a name plaque was then attached to the lonely grassy pitch, grave 1302. A small contribution Dana made in an effort to heal and honour, but also for the healing of a nation. He chose this pilgrimage since he was: ‘…one of those who believe you can heal something in your soul if you undertake a journey to the appropriate spot’.

However he was buried far from home. Maybe the healing process did improve when the grave received some small identity.

But the journey and procedures got real momentum with Nat’s re-burial home at – as cited by Dana – an appropriate spot – therefore a spot with identity, in the Chesterville cemetery, Durban, in 2014. Ultimately the stateless Nat came home to his country of birth – too late for a passport free from restricting conditions, but free at last.

Nat is now also remembered in a different way: The Nat Nakasa prize of The National Editors’ Forum for courageous journalism. A small tribute to thr brave journalism of Nat Nakasa in difficult times, whose life on earth ended in the tragedy, the talented young writer and journalist whose dream became a dream deferred.

(Information for this article was gathered via online sources, as well as in the article Nakasa, Nataniel: Johannesburg Johannesburg in Reef of Time by Ricci, Digby, (Ad Donker Publishers, 1986). Notes on authors whose articles were published in this book, provided more information on Nakasa, together with comments by other authors on Nakasa. The information on Dana Snyman’s article was found in an old press cutting from the Beeld newspaper, unfortunately date cut off, but most useful and informative).

About the author: Estelle was a senior official in city management before and after the 1994 democratic transition. She was in a unique position to be part of official processes like the privatisation of properties, negotiations, participation in important planning and discussions for change, witnessing the rise and fall of the BLA in Soweto, and much more. She has extensive experience as a private property facilitator and as a tourist guide in Soweto for close to 20 years.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.