Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

From about 05h00 on Saturday 8 June 2025 around 15,000 athletes are expected to gather in the cold pre-dawn outside the Pietermaritzburg Town Hall. Normally one would also have said it was pitch dark and very quiet.

But on 8th June this year (as it is every second year) the entire area will be well lit, music will be blaring from loudspeakers and there will be an excited buzz as new arrivals join the throng.

As the young set would say: “unless you’ve been living under a rock” every reader will recognise that we are describing the scene that builds up to the start of “The Comrades”. Over the years the organising committee has dropped the reference to “Marathon” but added the epithet - “the Ultimate Human Race”.

Gathering before the start (Wikipedia)

A dash for the cameras (Rob Arthur)

Nine times winner and 30 finishes overall Bruce Fordyce has frequently sardonically quipped that:

Only in South Africa would they call an event that is twice the standard distance, with at least 5 monstrous climbs and many other up and downs along the route, and with a time limit of 12 hours to complete, a marathon!

The first Comrades was run on 24 May 1921 which was Empire Day. This year marks the 99th event. No races were held from 1941 to 1945 because of World War II and there was a pause in 2020 and 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

So what interesting tidbits of historical interest should readers of The Heritage Portal be considering as they settle down to watch the Comrades on 8 June?

We are confident that there will be many readers who join the millions of viewers from around the world who will watch the live TV broadcast of the Comrades. Some will do almost nothing else for the whole day. Others will just drop in from time to time to watch at significant points during the day, and virtually “everyone” tunes in just before 17h30 to watch the annual drama that accompanies the final cut-off.

Talking of drama. Alan Robb, the Germiston Callies runner who has not only won the Comrades on 4 occasions, but also earned a total of 12 gold medals, 16 silver medals, 5 bronze medals and 9 Bill Rowan medals (which makes 42 finishes), was once given the “honour” of firing the pistol that signifies the end of the race and thereby ending the dreams of some athletes who may only be a few metres short! In accordance with tradition, Alan moved into position with a few minutes to spare. Just as he was about to turn his back on the field (so that he could fire the pistol without regard to who would be approaching the line), a huge cheer went through the crowd to greet Wally Hayward, one of the “G.O.A.Ts” of Comrades with 5 wins but who at the age of 80 years was attempting to break the record he set the previous year of being the oldest athlete to complete the gruelling event. Hayward still had about 120 metres still to run and just over 2 minutes to do it in. Worst of all for Alan Robb - Hayward also ran in the colours of Germiston Callies!

As he turned, Alan Robb said a silent prayer, willing Hayward forward. To his great relief, he was able to see the figure of Hayward pass over the line on his left-hand side about 30 seconds before he pulled the trigger.

At the other end of the race i.e. the winning end (though every athlete who has ever completed a Comrades - and there are now over 130,000 who can boast of having done so at least once - will tell you: “Every Comrades finisher is a winner”) we can also talk of fine margins.

The closest finish occurred in 1967 when Manie Kuhn beat the previous year’s winner Tommy Malone by one second, as Malone inexplicably collapsed a few metres from the line and was overtaken by Kuhn as he literally crawled on towards the finish.

In my book Summit Vision I commented:

By the way whenever I have read accounts of that finish in the past i.e. before writing this book, I always thought that it would have been a much more generous gesture if Manie Kuhn, instead of passing Malone who was on his hands and knees having collapsed metres before the tape, had stopped and helped his “Comrade” to cross the line together with him. But now I have researched the matter further and discovered that not only had Tommy Malone beaten Kuhn into second place by a time of 17 minutes and 39 seconds the previous year (1966) but that Manie Kuhn had finished second (in 1964 behind Jackie Meckler) and third (in 1965 behind Bernard Gomersall) in other prior races. He must have thought: “It’s now or never!”.

For his part Malone never held any grudges against Kuhn and I have heard that he always used to chirp: “Manie beat me by 1 second. That means I’m still 17 minutes and 38 seconds to the good!”

The second closest victory in the race occurred in 2023 when Tete Dijana outsprinted Piet Wiersma to win by a margin of only 3 seconds.

It has often been said that the most disappointed athlete on the “winner’s podium” has to be the athlete in second position. First has achieved his goal, third is just happy to be included, but second... it hurts, and often there is some bitterness, even self-recrimination (“why did I do this instead of that?”, “what do I have to do to improve next year” etc). Without doing a detailed analysis, we suspect that a runner who has finished second often wins the next year or in a subsequent race. Fordyce (who once came second to Alan Robb), Wiersma (second to Dijana but winner last year), Nick Bester (second to Fordyce) and Manie Kuhn are all examples that readily spring to mind.

But let us go back to the beginning of Comrades, which was founded by Vic Clapham who was a veteran of the Boer Wars and had also served in the First World War where he observed that even overweight and unfit soldiers became lean and fit with the regular exercise of marching daily! His idea was to commemorate the fallen and injured soldiers with an arduous but in his mind achievable endeavour. Although he was the founder and also the race secretary for many years, Clapham never himself ran the Comrades!

Bust of Vic Clapham at Comrades House (Wikipedia)

Comrades House, home of the Comrades Marathon Museum (Wikipedia)

He tried more than once to get his idea off the ground. He was eventually able to get permission and borrowed £1 (yes, one pound) to finance the venture. Today the Comrades has three major sponsors and 16 “suppliers” who contribute millions of rand to the staging of the race, in exchange for advertising and branding opportunities. And the competing athletes also raise millions of rand for various charities: so far nearly R5 million has been pledged for this year’s race and with some time to go this figure is likely to increase.

Vic Clapham’s appeal for prizes was successful with donations including watches, silver cups and a leather briefcase. There was even enough for him to have some small bronze medals cast which were handed to each finisher.

In my passage on Bruce Fordyce’s achievements in the Comrades in Summit Vision I wrote:

It might also interest many to know that despite his achievements on the road, Bruce made virtually no money directly from running. Sure, he was (and remains) a much sought after motivational speaker, and has written a few books about his running, and now has a more than useful website that provides training and other advice to runners. But he received no prize money for his wins. Even sponsorship deals were hard to come by. I’ve heard him recall that after his first victory a shoe manufacturer allowed him to buy his shoes “at cost”. After his second victory they allowed him 5 free pairs of shoes a year! So much for ‘sponsorship’.

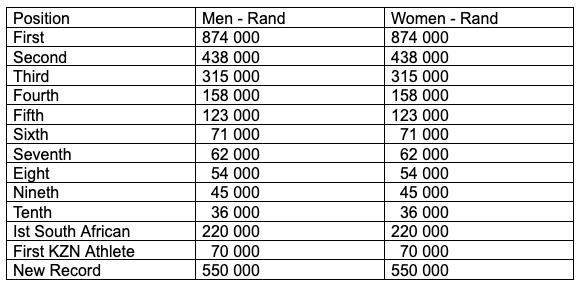

By contrast here’s a table of the prize money that will be on offer on 8 June 2025 (and we note the equality factor):

There are also age-group and team prizes.

We do not know if anyone paid an entrance fee in 1921 but today a South African runner pays R1 200, while an international athlete will pay R4 500.

In exchange for the entrance fee one gets a “goodie bag” and of course free access to and use of the refreshment points along the route, the assistance of the marshals, traffic police and first aid or medical facilities which all help to make the day in the sun a more tolerable experience!

In 1921 Vic Clapham had to borrow a pistol from a policeman who was observing the start to get the race on its way.

In Summit Vision I described the start of the Comrades in the year 2,000 in the following terms:

There can be few scenes in sporting endeavour like the start of the Comrades – over 22,000 excited athletes waiting in anticipation! Jackie Mekler describes the feeling he experienced before the start of Comrades in these terms:

The feeling one gets at the start of Comrades is quite different compared with standard marathons and the other races I had concentrated on over the past few years. Due to the extreme distance of the Comrades Marathon there is a far greater feeling of uncertainty. So much can go wrong. Its rather like going on an expedition into the unknown.

And of course in my case there was the added pressure that this was the fourth leg of the Nashua Millennium Big 5 Challenge. Fortunately negative thoughts are soon swept away by the what happens just before the start.

Over the course of 100 years a number of traditions have evolved to get the Comrades on their way.

First comes the National Anthem – one of the longest national anthems in the World but which has brought the Rainbow nation together in a way many thought impossible in 1994 just a few years before we were now lining up at the start of Comrades. “Nkosi Sikeleli Africa” – God bless Africa.

This is followed by the singing of “Shoshaloza” (the song that carried the Springboks to victory in the 1995 World Cup”) which is a traditional miner's song, originally sung by groups of men from the Ndebele ethnic group that traveled by steam train from their homes in Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia) to work in South Africa's diamond and gold mines. According to cultural researchers Booth and Nauright, Zulu workers later took up the song to generate rhythm during group tasks and to alleviate boredom and stress. The song was sung by working miners in time with the rhythm of swinging their axes to dig. It was usually sung under hardship in call and response style (one man singing a solo line and the rest of the group responding by copying him). It was also sung by prisoners in call and response style using alto and soprano parts divided by row. The late former South African President Nelson Mandela described how he sang Shosholoza as he worked during his imprisonment on Robben Island. He described it as "a song that compares the apartheid struggle to the motion of an oncoming train" and went on to explain that "the singing made the work lighter". In contemporary times, it is used in varied contexts in South Africa to show solidarity in sporting events and other national events to relay the message that the players are not alone and are part of a team.

For Comrades runners the song reminds them to shove up the hills (a thought that the cycling community caught onto when they started a cycle race between Pietermaritzburg and Durban and called it the “Amashovashova”).

Then follows the stirring theme to “Chariots of Fire” by Vangelis – ironically a film about British sprinters at the Olympics Games – but it is always that scene of them running along the beach that stirs the passion of an ultra-distance athlete.

As the strains of Vangelis fade the tension becomes palpable as the athletes await the recording of Max Trimborn’s imitation of a cock-crow. In 1948, local runner Max Trimborn couldn't contain his nervous energy on the starting line of the Comrades Race. So he cupped his hands, filled his lungs and issued a hearty rooster crow. The other runners so enjoyed this display that they demanded repeat performances in subsequent years. Trimborn obliged for the next 32 years, sometimes adorning himself with feathers and a rooster vest. By the time of his death in 1985, Trimborn's crowing had been preserved on tape. These days, greatly amplified, it still starts the Comrades Marathon...”

And of course the Mayor of the host city fires a pistol shot but the back-markers hardly ever hear that. When Vic Clapham’s field started in 1921 they stood in one line across the road. Today it can take the last athlete several minutes to actually reach the start line!

And if music is associated with the start of the Comrades, it also features at the finish. Seconds after the pistol shot signifies the final cut-off a bugler plays the “Last Post”, a fitting reminder of the reason Vic Clapham created this event in the first place.

Apart from the wonderful sense of satisfaction that one gets for completing the Comrades all one really gets is a small medal.

The emotion at the finish (Rob Arthur)

The first 10 men and the first 10 women each receive a gold medal. Men finishers in positions 11 to finishers under 5h59 get a Wally Hayward medal (5 time winner Wally was also the first runner under 6 hours). Women finishers in positions 11 to finishers under 6h59 get a Isavel-Roche Kelly medal (who broke the seven hour barrier for women runners). Men finishers from 6h00 to 7h29:59 and women finishers get a silver medal. Everyone finishing between 7h30 and 8h59:59 receive a Bill Rowan medal, 9h00 to 9h59:59 a Robert Mtshali medal, 10h00 to 10h59:59 a bronze medal; and finally 11h00 to 11h59:59 a Vic Clapham medal.

Vic Clapham Medal (Wikipedia)

Hopefully you’ve enjoyed reading a bit about the Comrades.

But here’s a special challenge to you: right now - decide to do the Comrades in June 2026. Age is not a factor - even Wally Hayward’s record of 80 years has been broken (by 81 year old Polokwane bricklayer Johannes Mosehla who is still working, and running at a ripe old age!). Nor is your current state of fitness. In March 1999, as an overweight, and unfit, 45 year-old I committed to not only doing (and did do) the Comrades, but the Dusi Canoe Marathon, the Midmar Mile Swim, the Cape Argus Cycle Tour and an ascent to Uhuru Peak on Mt Kilimanjaro all in one year to celebrate the advent of the new Millennium. I recorded this journey and the life lessons I learned in the process in my book Summit Vision. Drop me an email (legaleagles@srvalley.co.za) if you would like a copy (R300 plus courier fee of R150).

Graeme Fraser (BA LLB LLM HDip Tax) is a corporate and commercial law consultant. He has a passionate interest in legal writing and in particular the collection of cases from South Africa and other jurisdictions. Has has co-authored, self-published and marketed over 23 books since 2010. Graeme also wrote "Summit Vision" an account of the lessons he learned creating, co-ordinating and completing the Millennium Big 5 Challenge in the year 2000: Dusi Canoe Marathon, Midmar Mile Swim, Cape Argus Cycle, Comrades and an ascent to Uhuru Peak on Mt Kilimanjaro.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.