Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Middelburg is one of those towns one usually bypasses while travelling to the Loskop Dam, the Kruger Park or the Mpumalanga Escarpment, not realizing it offers interesting sightseeing opportunities.

There is a historic Dutch Reformed Church established by the controversial Reverend Frans Lion Cachet in 1866, when the community was still known as Nazareth. Later the town’s name was changed to Middelburg, as it was midway between the two principal Transvaal towns of Pretoria (Tshwane) and Lydenburg (Mashishing).

It contains an attractive railway station erected when the NZASM Delagoa Bay line was laid. By the time this railway line reached Middelburg, the town had already become an agricultural centre of some importance and the hub of the regional transport roads. Its railway station was expected to become important because of the nearby coal fields. As a result more care than normal, went into the design and construction of this station building.

Then, there is the very interesting and historical Municipal Cemetery, which one enters from Bhimy Damane Street.

For anyone interested in the history of the Voortrekker migration, there is the grave of Carolus Johannes Trichardt, eldest son of Louis Trichardt who was the leader of the ill-fated Trichardt Trek of 1835 – 1838, who explored large stretches of East Africa for possible settlement areas for the migrants.

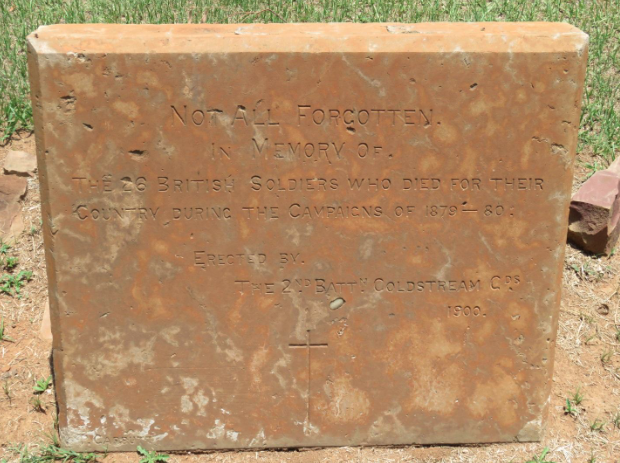

For a student of the old Transvaal Republic, the cemetery contains a memorial to 26 British Soldiers who died in the campaigns of 1879 to 1880, following its 1877 Annexation by Great Britain.

For the Anglo Boer War enthusiast, there is an impressive Garden of Remembrance dedicated to Imperial Soldiers whose remains were interred here during and after the war. In the Dutch Reform precinct there are the tombstones of Jack Hindon and Henri Slegtkamp, two legendary Boer scouts.

For the musicologist, there is the grave of the lyricist who supposedly composed the well-known Afrikaans song ‘Sarie Marais’.

Lastly, for the military historian, there is a grave of a Union soldier who was wounded at the famous 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, during the American Civil War.

The historical precincts of this cemetery are compact, easily accessible and well maintained.

Upon entering this cemetery, the Garden of Remembrance for Imperial Soldiers is just to the right (east), of a more recent precinct.

In front (south) of the Garden of Remembrance and east of the Jewish precinct is a somewhat enigmatic memorial stone erected by the 2nd Battalion Cold Stream Guards in 1900, which reads, ‘Not All Forgotten. In Memory of the 26 British Soldiers who died for their Country during the Campaigns of 1879-80.’ There is a small cross engraved at the lower middle of this stone. The name of the stonemason engraved on the left hand side at the bottom seems be that of ‘P. Carbutt’. Unfortunately the 3rd letter of the surname is badly weathered and hard to read.

The question is which 26 British Soldiers this memorial commemorates? There are no other tombstones to British Soldiers of this period to provide any clues. The wording indicates it was not necessarily dedicated to soldiers of the Cold Stream Guards, but probably to all British soldiers who died in the area during the 1879-1880 campaigns.

Presumably, this memorial commemorates the 13 British soldiers who were killed during the second campaign of the second Sekhukhune War of 1879, in the vicinity of the present towns of Burgersfort and Steelpoort.

It probably does not commemorate Colour Sergeant John Pegg of the 13th Regiment, who died of his wounds on 28 October 1878, during the first campaign of the second Sekhukhune War and whose grave is near the Steelpoort Station. Pegg was apparently the first British military casualty in the Transvaal, but would not be commemorated by this memorial stone, since he died before 1879.

It is uncertain which other 13 British soldiers this stone commemorates. One is inclined to assume the memorial also commemorates soldiers of the 94th and the 58th Regiments who died while besieged at Lydenburg, Standerton and Marabastad (a few kilometers east of where the R519 joins the N1 near Pietersburg/Polokwane), during the First Boer War.

According to Duxbury, British deaths at these three besieged towns were as follows:

- Lydenburg - 4 killed or died of wounds/disease;

- Standerton - 5 killed or died of wounds/disease;

- Marabastad - 5 killed or died of wounds/disease.

The above figures may, or may not be totally accurate, as for instance, in the Garden of Remembrance at the new Standerton Cemetery, there is a granite stone commemorating nine soldiers; eight from the 94th Regiment and one from the 58th Regiment, who died during the siege.

Monuments, memorials and graves relating to the First Boer War are quite rare and only found at the battlefields of Bronkhorstspruit, Laingsnek, Rooihuiskraal, Skuinshoogte, Majuba Hill and the Mount Prospect Cemetery, as well as at some of the seven towns where British garrisons were besieged: Pretoria, Potchefstroom, Rustenburg, Wakkerstroom, Standerton, Lydenburg and Marabastad.

Memorial stone to 26 British soldiers who died in campaigns of 1879 – 1880 (SJ de Klerk)

The Anglo Boer War Garden of Remembrance on the other hand contains the remains of 503 Imperial Soldiers, of which 109 were killed in action or died of their wounds. It is the largest repository of remains of Imperial Soldiers in Mpumalanga, other than the Standerton Garden of Remembrance, which contains the remains of 549 soldiers.

After being defeated at the Battle of Diamond Hill (also called Donkerhoek) on 11 and 12 June 1900, the Boer forces retreated further east along the Delagoa Bay railway, past Middelburg. They formed a defensive line ranging from about 40 kilometres north-west of Belfast to about 35 kilometres south-east of it. The topography of the area was ideal for the Boers to make a final effort to halt the British advance along the railway. To the north and north-east of Belfast the plains and rolling hills of the Highveld give way to mountains and ravines, while to the east there are various springs rising amongst marshy terrain. This made it difficult to outflank the Boer line, while providing escape routes if needed.

For both Boers and British, control of the Delagoa Bay railway line was of utmost importance. The Boers to maintain their only remaining link with foreign countries via Delagoa Bay (Maputo) and for the British to substantiate their claims that the Boers have been defeated. The Boer force of 5 000 men under General Louis Botha faced for the first time virtually the whole of the British Field Force in South Africa, consisting of the main British force under Field Marshall Roberts and the Natal Field Force under General Buller, totaling close to 20 000 men. Although heavily outnumbered, the greater mobility of the Boers somewhat compensated. The last set piece battle of the war took place here from 21 to 27 August 1900. This battle called the Battle of Dalmanutha or Bergendal, was one of the most severe of this war.

During the course of the seven day battle, General Buller identified a small rocky hill at the farm Bergendal, where a 70 strong contingent of the ZAR Police, supported by 40 Austrians had entrenched themselves some distance ahead of the main Boer line, as the weak point where it could be breached. Following an intensive three hour bombardment and a powerful infantry attack by the Rifle Brigade, the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, supported by the Devonshire Regiment and the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, the British broke through here on 27 August 1900. This is the same hill where an impressive monument was unveiled in August 1971 to the memory of those burghers who died in this area during the war. This monument is situated south-east of Belfast next to the N4.

Boer Memorial at Bergendal (via Wikipedia)

The defeated Boer commandos then separated with some retreating northwards via Dullstroom towards Lydenburg, others to Barberton and some further east along the railway line. The Boers realised the futility of opposing the stronger British forces through set piece battles and instead embarked on their guerilla war campaign.

During the guerilla war phase, Middelburg became an important Imperial military centre accommodating about 30 000 Imperial soldiers. Many small battles and skirmishes occurred in the Eastern Transvaal as Imperial graves in the Gardens of Remembrance at Middelburg, Belfast, Machadodorp, Waterval Boven, Waterval Onder, Lydenburg, Ermelo and Standerton testify.

While stationed at Middelburg, Major S. R. Rice of the 23rd (Field) Company Royal Engineers designed the circular corrugated iron blockhouse, of which the first type of this new blockhouse was erected on 11 March 1900 at Gun Hill near Middelburg. This easily erected and cheap to manufacture blockhouse played a vital role in restricting the mobility of the Boer Commandos during the guerilla war.

The Imperial forces were very effective in implementing their ‘Scorched Earth’ policy in the Eastern Transvaal. The success of Colonel Benson’s No. 3 Flying Column was examined in a previous article on the Primrose Cemetery (click here to read). When the Boer Delegates met in May 1902 to discuss possible peace proposals, General Louis Botha presented a gloomy picture to his fellow delegates of the east and south-east Transvaal. Reviewing district after district he showed that some of them could hold out for a month or two, while others were on the brink of starvation. In the whole of the Transvaal he estimated there were no more than 10 816 burghers in the field of whom nearly a third had no horses. His overview convinced the majority of Boer delegates that there were no prospects for success and the best possible peace terms should be sought.

At the entrance to the Middelburg Garden of Remembrance is a stone indicating the restoration of this precinct by the SA War Graves Board in 1972.

Situated towards the northern end in the Garden of Remembrance is a substantial monument erected by the War Graves Board in 1962, providing the names and regiments of all soldiers buried or subsequently reinterred here. The place names where the soldiers were killed and presumably interred from are engraved at the bottom of this monument: Pan Station, Roodepoort, Wilmansrust, Wonderfontain Station, Groblersrecht, Middelkraal, Blinkwater and Brugspruit (now Cluwer).

The remains of Imperial soldiers who died in action or from their wounds and reinterred in this Garden of Remembrance seem mainly those killed during the guerilla war.

With some exceptions, most of the Imperial soldiers who were killed at the Battle of Dalmanutha/Bergendal were buried at Military cemetery at the Bergendal battlefield, or later reinterred at the Machadodorp Garden of Remembrance.

The majority of graves are indicated with steel crosses bearing the name, rank and regiment of the deceased soldiers. There are in excess of 400 such steel crosses erected.

There are only a few monuments that refer to specific battles or skirmishes. One was erected by the State of Victoria to 17 Australian soldiers killed at the battle of Wilmansrust on 12 June 1901, which is incorrectly indicated on the monument as 7 June 1901. Another is an attractive white marble monument to 13 members of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers who died in Middelburg during the period 1900-01. The epitaph on this monument ends with the stirring slogan, ‘Nec Asperra Terrent’ (Difficulties be Damned).

There is an impressive and unusual tombstone to Lieutenant Rainy Anderson of the Royal Engineers who died on 11 July 1901 from wounds received the previous day at Zeekoeigat (near the present Loskop Dam). This grave together with those of two other soldiers are grouped together and enclosed by an attractive iron fence. The two other soldiers were probably killed in the same skirmish as Lieutenant Anderson, as the dates of death broadly correspond.

Interestingly, there is also another tombstone in the hills of the farm De Voetpadkloof near Loskop Dam to Lieutenant Anderson. According to local lore a woman from overseas used to visit this grave every few years to clean and cover it with flowers. It may be that the remains of Lieutenant Anderson were reinterred at the Municipal Cemetery some years after the Boer War, when his original grave at the farm could no longer be properly maintained. Lieutenant Anderson served with General Beatson’s column to which he had been appointed Intelligence Officer, shortly before his death. A memorial tablet was erected to his memory in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. This tablet must have been transferred to Anderson’s present grave, quite possibly when his remains were reinterred from the farm grave, as his grave contains a loosely placed marble tablet, regretfully now damaged, with the inscription, ‘This tablet was erected in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London 6th January 1901’.

Grave of Lieutenant Rainy Anderson. The tablet previously erected in St Paul’s London is visible next to the helmet. Note the empty sheath a symbol of death. (SJ de Klerk)

To the north of the Imperial Garden of Remembrance is the Anglican Section. There is a tombstone of a Thomas Begbie who died on 3 August 1912 aged 67 years. His engineering works (the largest in the Transvaal) situated in the City and Suburban suburb of Johannesburg was destroyed by a massive explosion on 24 April 1900. The ZAR Government was angered by this explosion and suspected sabotage and charged Begbie but he was acquitted. After the war he relocated his factory to Middelburg.

To the south-east of the Imperial Garden of Remembrance is the oldest Dutch Reformed precinct in this cemetery. The oldest grave found in this precinct was that of H. van der Linde who died in 1880, aged 30 years.

A very historical grave in this precinct is the one of Carolus Johannes Trichardt (born at Boschberg now Somerset East 1811 and died Middelburg 1901) and his wife Zacharya Geertruida (nee Erasmus 1823 - 1901). They died within two weeks of one another and are buried in the same grave. Carolus Trichardt was the eldest child of the Voortrekker leader Louis Trichardt, who died in Delagoa Bay (Maputo) in October 1838. The Trichardt migration departed the Cape Colony in 1835.

Shortly after arriving in April 1838 at Delagoa Bay, numerous members of the Trichardt migration started falling ill and dying from the effects of malaria acquired during the trek through the Lowveld and while at Delagoa Bay. Louis Trichardt therefore instructed his son Carolus to travel to the north to seek suitable settlement areas for the survivors. During the third week of June 1838, Carolus travelled by coastal trader to Imhambane and then inland for about 500 kilometers but found the region unsuitable for cattle farming. He then continued his trip with this ship to Sofala stepping ashore in October 1838 and again travelled inland for a distance of about 350 kilometers. He reached the area where the City of Salisbury (now Harare) was later established and might have recommended it as a settlement area, if his father and other members of the Migration had survived. His travels lasted for about fourteen months. Having been the only Voortrekker who had travelled extensively along East Africa, he was able to inform other Voortrekkers that the area today known as the Gauteng and Mpumalanga ‘Highveld’ offered the best prospects for settlers of European descent.

Grave of C. J. and Z. G. Trichardt. (SJ de Klerk)

Very close to the Trichardt graves is an attractive tombstone to a Boer burgher, Jacob Philippus Maré who was wounded in the battle of Dullstroom on 19 December 1901 and died on 11 February 1902.

There are a number of other interesting tombstones in this precinct dating back to the 1890s.

One is a poignant tombstone with the epitaph ‘Thalitha Khumi’ dedicated to the ‘Teeder bemind Dochtertje van J. B. en A. E. de Kock’, (dearly beloved young daughter) who died at the tender age of one year, one month and twenty days on 25 July 1893. Thalitha is an uncommon feminine name meaning ‘little girl’ in Aramaic, given in reference to the Biblical story in the Gospel of Mark in which Jesus Christ was said to have resurrected a dead child with the words ‘Talitha cumi’ or ‘Talitha kum’, meaning ‘Little girl, I say to you, arise!’

Note the proverb ‘Talitha Khumi’ (Little girl I say to you arise!) on tombstone of the De Kock infant girl. (SJ de Klerk)

There is another attractive tombstone of a Boer burgher who died during the war. It is situated slightly to the north, amongst graves of inmates from the Middelburg concentration camp. It is of Phillipus Charel Bronkhorst who was killed on 11 March 1901 at the age of 17.

Just to the north of Bronkhorst’s grave and immediately east of the pathway, lies the tombstone of the renowned Boer scout Jack Hindon (1874 – 1919). The epitaph in Afrikaans on his tombstone reads, ‘Ter gedagtenis aan my man Kaptein Jack Hindon tot die laaste druppel bloed onverskrokke, dapper, getrou en goed’, (To the memory of my husband Captain Jack Hindon, to the last drop of blood intrepid, brave, loyal and good). Hindon joined the British Army and arrived in South Africa at a youthful age to serve in the then Zululand (KZN Province). Due to alleged victimisation he deserted and in 1888 moved to Wakkerstroom where he worked as a builder. He associated himself fully with the Boer cause and obtained citizenship of the ZAR because of voluntary services rendered during the Jameson Raid (1895-1896). Having joined the ZAR Police (ZARP), he departed to the Natal front on the outbreak of the Boer War. Shortly before the Battle of Spioenkop (24 January 1900) Hindon, together with Henri Slegtkamp, Albert de Roos and a handful of burghers, made a name for themselves by occupying a hill in the Thabanyana mountain range for several hours, notwithstanding a murderous bombardment. During June 1900 he joined the Danie Theron Reconnaissance Corps and was subsequently appointed head of a small group of about 50 men tasked with disrupting British communication lines. During October 1900 he was promoted to Captain and soon became well known for his train wrecking exploits. Only a few weeks before the end of the war he fell ill and surrendered to the British. After the war he married an Afrikaans speaking woman (Martha Pauline Coetzee) who Harald Pakendorf as a young boy recalls working as librarian in Middelburg. Hindon died in 1919 after suffering from poor health for some time. This tombstone was probably erected some years after his death as the epitaph is written in modern Afrikaans and not the more Dutch oriented early Afrikaans, spoken or written in 1919.

Tombstone of Jack Hindon (SJ de Klerk)

Very close to Hindon’s grave is the grave of Jacobus Petrus Toerien (1859 – 1920), an early Afrikaans writer who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Jepete’. A tablet, undoubtedly placed at a much later date on his grave site reads, ‘JEPETE verantwoordelik vir die vrye vertaling van Sarie Marais’ (JEPETE responsible for the translation of Sarie Marais).

Toerien settled in Middelburg during 1896 where he became the editor of the ‘Barberton and Middelburg Herald’ as well as the ‘Belfast en Middelburg Heraut’. Although no definite facts have surfaced that he composed the song ‘Sarie Marais’, the available evidence indicates that he may have composed it for his wife Susara (Sarie) Margaretha Maré. She was against the popularisation of the song as she considered it to be her personal property and instructed one of her daughters to destroy the original verse after her death. ‘Sarie Marais’ originally ‘Sarie Maré’, seems to be based on the words and melody of the American civil war folk-song ‘Ellie Rhee’.

Tombstone of J. P. (Jepete) Toerien who may have composed the song ‘Sarie Marais’ (SJ de Klerk)

Slightly to the north-west of the grave of Toerien is a monumental tombstone to Hendrik Frederik (Henri) Slegtkamp (1873 – 1951), another famed Boer scout from the Boer War.

Slegtkamp emigrated to the ZAR from the Netherlands at a young age apparently because of a desire for adventure. At the Battle of Tabanyama (20 January 1900) a prologue to the battle of Spioenkop, Slegtkamp won special recognition when he, Jack Hindon and Albert de Roos ascended a hill which had been abandoned by the Boers, on their own initiative and subjected the left flank of some British soldiers to heavy fire. Under the impression that the hill was heavily garrisoned by the Boers, the soldiers retreated. The morale of the other burghers having been strengthened by the action of Slegtkamp, Hindon and De Roos, re-occupied the hill. Thus the way was paved for the Boer victory at Spioenkop four days later. Afterwards he was known as ‘Slegtkamp of Spioenkop’ and this phrase is also engraved on the horizontal slab on his tomb. He served as Hindon’s second in command of the corps formed to disrupt British communication and railway lines. From the beginning of 1902 until peace was declared, Hindon’s corps was mercilessly harassed between the blockhouse lines by the British. When Hindon surrendered very shortly before the end of the war, Slegtkamp succeeded him as Captain of this force.

Tombstone of Henri Slegtkamp. The letters DTD means ‘Dekoratie voor Trouwe Dienst’, a medal issued in 1920 as a retrospective award for distinguished and meritorious service to Boer Officers, who served in Boer War. (SJ de Klerk)

Lastly, there is an intriguing tombstone situated immediately north of the Jewish precinct. It is the one of Dr. John Tower Blake (1840 -1927), of whom unfortunately we know very little. His epitaph reads, ‘In Memory of Dr. John Tower Blake. Born in Providence Rhode Island, 1st December 1840. Wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg USA. Died in Middelburg Transvaal, 22nd July 1927.’

In an email exchange between Robin Smith on behalf of the South African Military Society and Professor Carol Reardon from the USA, dated 6 June 2011, and accessible on the internet, the following comment was posted, “John T. Blake served as 1st Sergeant of Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Artillery commanded at Gettysburg by 1st Lieutenant T. Frederick Brown. Blake was severely wounded in the wrist on 2 July 1863, probably in the repulse of Brigadier General Ambrose Wright’s Georgians. Blake enlisted in Providence on 13 August 1861 and was appointed to the rank of Sergeant. He was promoted to the rank of 1st Sergeant on 5 February 1863, and commissioned a Second Lieutenant on 28 October 1863 to Battery, 1st Rhode Island Artillery. Apparently he served through General Grant’s Overland campaign and the opening phases of the Petersburg campaign. He mustered out of service on 19 August 1864.”

The Battle of Gettysburg was fought from 1 to 3 July 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania by Union and Confederate forces. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the turning point of this war.

Union General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, thereby stopping Lee’s invasion of the North.

After the unsuccessful outcome of this battle, Lee and his battered army retreated back to Virginia. Between 46 000 and 51 000 soldiers from both armies were casualties from the three day battle, apparently the most costly in US history.

On 19 November 1863, President Lincoln used the dedication ceremony for the Gettysburg National Cemetery to deliver his famous and historic Gettysburg Address.

The Middelburg Cemetery is fenced, very well maintained and open to visitors.

The local Middelburg Municipality deserves to be complimented on the high standard of maintenance at this cemetery.

The author also wishes to express his appreciation to Sarah Welham for locating the grave of Dr. Blake and noting the epitaph on the tombstone of the De Kock infant girl.

Main image: Beautiful marble grave in the Middelburg Dutch Reformed precinct of Martha Wilhelmina Zacharia Viljoen (nee Trichardt). Note the drape over the tombstone symbolizing the passing from one world to the next. Perhaps where the saying ‘you are curtains’, originates. (SJ de Klerk)

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South Africa's historical cemeteries.

References:

- Childers E. Editor. Vol. 5. 1907. The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899 – 1902. Sampson Low, Marston, and Company Ltd. London.

- De Jong R. C. Van Der Waal G-M. Heydenrych D. H. 1988. NZASM 100: The Buildings, Steam Engines and Structures of the Netherlands South African Railway Company. Chris van Rensburg Publications, Melville.

- Dictionary of South African Biography Vol V. 1987. Creda Press.

- Dooner Mildred G. Reprint 1980. The Last Post: A Roll of all Officers (Naval, Military or Colonial) who gave their lives for their Queen, King and Country in the South African War, 1899 – 1902. J. B. Hayward & Son. Suffolk.

- Duxbury G. 1981. David and Goliath: The First War of Independence 1880 – 1881. SA National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg.

- Eicher David J. 2002. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. Pimlico.

- Grobler J. 2018. Anglo Boer War (South African War 1899 -1902) Historical Guide to Memorials and Sites in South Africa. 30̊ South Publishers.

- Kinsey H. W. Sekukuni Wars (Part II) December 1973. Military Historical Journal Vol 2 No 6, Published by the South African War Museum.

- Oosthuysen H. (Not dated), 101 Kerke: ʼn Huldeblyk aan die ryk geskiedenis van ons kerke in Suid Afrika. Hong Kong.

- Pakendorf H. 2018. Stroomop – Herinnering van n koerantman in die apartheid- era. Penguin Random House, South Africa.

- Pretorius F. Editor. 2017. Scorched Earth. Tafelberg.

- Schultz B. G. 1974. Die Slag van Bergendal (Dalmanutha). Dissertation for the Master of Arts degree. University of Pretoria.

- Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Vol I. 1976. Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing. Tafelberg Uitgewers Beperk, Kaapstad.

- Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Vol II. 1986. Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing. Nasionale Boekdrukkerye, Goodwood, Kaap.

- Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Vol III. 1977. Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing. Tafelberg Uitgewers Beperk, Kaapstad.

- Van der Westhuizen Gert & Erika. Not dated (2002?). Guide to the Anglo Boer War in the Eastern Transvaal: 1899 – 1902 100 years. Transo Press, Roodepoort.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.