Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The Krugersdorp Concentration Camp and the graves of its victims are still visible today in the old Burgershoop Cemetery.

Let us go back to eight months after the outbreak of the Second South African War (1899–1902). In June 1900, following the annexation of the Orange Free State, British troops under Major-General Archibald Hunter occupied Krugersdorp without resistance. Magistrate J.C. Human formally handed over administration of the town, and martial law was declared. The Union Jack was hoisted at a public ceremony held in front of the Old Magistrate’s Court on Commissioner Street, signifying the beginning of British military rule.

The British garrison set up its headquarters—according to local tradition—in Kilmarnock House on the corner of De Wet and Begin Streets in Krugersdorp North. A blockhouse was also constructed on the Monument hillside to oversee the town. It was manned by seven soldiers and four Black men acting as servants and watchmen. This blockhouse still exists today, situated in the park opposite Monument Primary School on the corner of Sarel Oosthuizen and Sarel Potgieter Streets.

Under martial law, movement was tightly controlled. Public gatherings were prohibited, and permits were required for anyone wishing to travel or even access the railway platform. Shortages of food and essential goods worsened when shops were forced to close at the outbreak of war. However, a few stores such as Hompes and Seehoff, Harvey Greenacre, McCloskie, and Te Water reopened after the British occupation, providing crucial support to the impoverished townspeople—many of whom had relied on now-suspended gold mining operations.

To address these hardships, the Krugersdorp Women’s League was established. Initially focused on poverty relief, the League later expanded its work to support residents of the newly formed Krugersdorp Concentration Camp.

In October 1901, a Health Committee was re-established to oversee public health in accordance with pre-war regulations. Under Proclamation 21 of 1900, all infectious diseases had to be reported, with doctors receiving a fee of 20 cents per case. Proclamation 10 of 1901 placed the responsibility for inquests in cases of sudden or suspicious deaths on the Resident Magistrate. All births and deaths had to be officially registered.

With the annexation of the South African Republic (ZAR), all citizens became British subjects. Townspeople were forbidden to support the Boer commandos. Each household was issued a permit following an inventory of its belongings to prevent provisions from being passed to Boer fighters. Nevertheless, several elderly residents—Dr. van der Merwe, Landdrost J.C. Human, Mr. M.W.P. Pretorius, Mr. S. van Blommenstein, Mr. A. Vorster, Mr. A. te Water, and Mr. D. Grundlingh—succeeded in smuggling intelligence to the commandos using notes tied to stray dogs. Magistrate Human was placed under house arrest for his role but continued to assist the Boer forces covertly.

Life in Krugersdorp during the war was exceptionally harsh. With no steady income and no money circulating, townspeople struggled daily for survival. Formal education ceased: the local Dutch Reformed (NG) Church school closed at the start of the war. In 1901, the British opened an English-medium school. In response, community leader Mr. J.H. Grundlingh established a private Dutch-medium school with 100 students, employing Misses F. van Binnedyk and H. Putten at five pounds per month.

The Krugersdorp Concentration Camp

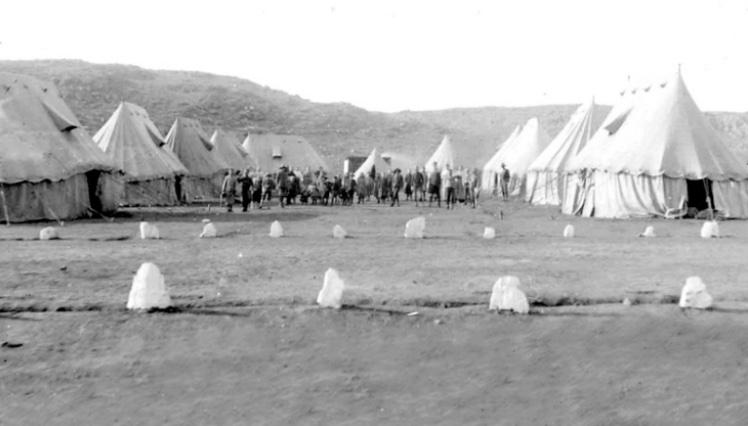

Though relatively small in comparison to others, the Krugersdorp Concentration Camp was no exception in terms of suffering. Located against Monument Hill—on the site now occupied by Yusuf Dadoo (formerly Paardekraal) Hospital and Coronation Park—the camp held over 6,000 women and children by the end of 1901.

Krugersdorp Concentration Camp

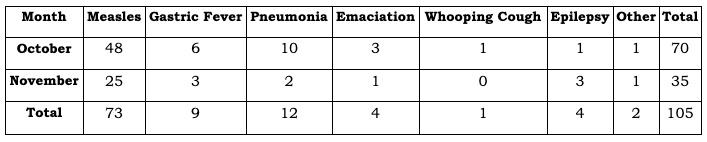

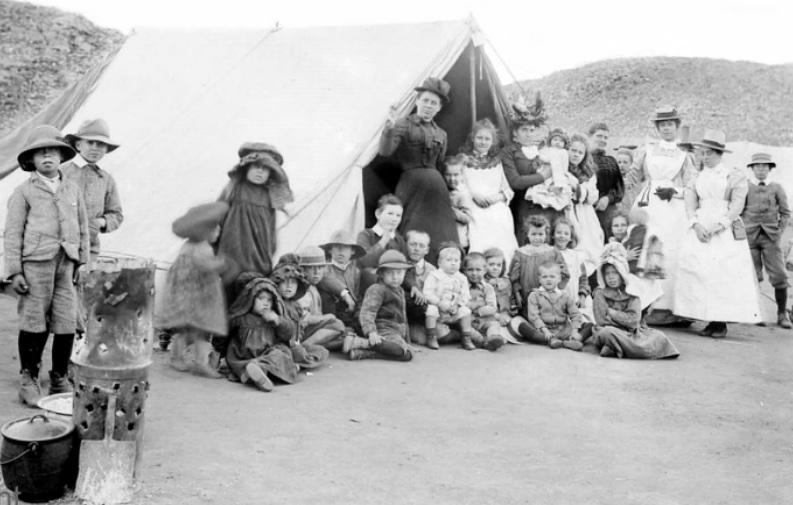

Unsanitary, overcrowded, and poorly managed, the camp experienced severe epidemics of measles, pneumonia, and dysentery. Malnutrition and polluted water worsened conditions. October and November 1901 were particularly deadly:

Child Deaths in Krugersdorp Concentration Camp (Oct–Nov 1901)

After administration was transferred from military to civilian control under Mr. Tomlinson and Dr. Aymard, mortality rates improved. The town’s Ladies’ Commission expanded its support to camp families, focusing especially on food provision.

Rations were divided into two classes:

Rations per Week – Krugersdorp Concentration Camp

Additional maize meal and milk (for children under 2) were distributed when available. However, family size was not considered in rationing, leading to widespread malnutrition. Contaminants in food were also reported. Families had to scavenge for firewood or cow dung to cook. Some women worked for British soldiers—for instance, doing laundry—in return for better treatment.

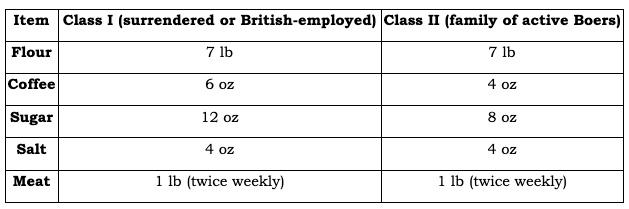

Women and children in Krugersdorp Concentration Camp

A large tent in the camp doubled as a church and school. For many Boer children, this was their first formal education—taught in English, part of Britain’s policy to anglicise Afrikaners. Many teachers remained in South Africa after the war, forming the core of the emerging education system.

The camp was officially closed in November 1902 following the peace treaty in May. According to 89-year-old Mrs. Rachel Lindhout-Fourie, her grandfather “Oom Klasie” helped bury victims, who were initially interred at the camp site and later reburied at Burgershoop Cemetery. The graves, uniform and unnamed due to the reburials, are said to contain up to four individuals each—accounting for the estimated 1,800 dead.

Krugersdorp Native Refugee Camp

Less widely acknowledged is the existence of one of the largest Native Refugee Camps in the region. In July 1901, many Black residents of the western Transvaal sought refuge with British forces. To enforce the displacement of Boer women and children, Black farm labourers were also removed and resettled.

The Native Refugee Camp was first established on the farm Roodekranz No. 83 IQ near Krugersdorp, and later moved to Waterval No. 74 IQ due to better water access. Farming began under a self-sustainment policy, and by September 1902, the British government had negotiated a crop-sharing agreement with the landowner, Mr. A.H.F. du Toit.

The Krugersdorp Native Refugee Camp housed 3,382 people in December 1901. Of these, 1,288 Black men served the British Army, while a small number worked in private homes.

Conditions were dire—often worse than in the white camps. Disease and famine claimed many lives, with pneumonia, measles, and dysentery being the leading causes. Missionaries, such as Reverend Farmer, reported on 23 November 1901:“We have to work hard all day, but the only food we get is mealies and mealie meal—and we have to buy this with our own money. Meat is unavailable at any price, and we are not allowed to shop freely.”

The camp was abolished in October 1902. Some inhabitants refused to return to Boer farms, hoping instead for better lives under British rule. However, famine persisted in the region, and the Krugersdorp grain depot was retained to support the devastated Black communities.

Aftermath of the War

The war reshaped Krugersdorp society. Assistant Resident Magistrate Lt. Phillips took over administration as families and prisoners of war returned. For the first six months post-war, repatriation and reconstruction dominated public life.

A commission under the Assistant Resident Magistrate processed Boer claims for war damage compensation. Although aid—such as food and farming equipment—was available on credit, many Boers fell into severe debt.

Large numbers of impoverished Afrikaners settled near the Burgershoop Brickfields, where they began producing hand-moulded clay bricks used in many early Krugersdorp buildings. This clay was sourced from the wetlands near what is now Harlequins Rugby Club.

Today, little physical evidence remains of either the White or Native camps. The White camp site became Coronation Park in honour of King Edward VII’s coronation in 1902. The Native camp area was absorbed into the old Krugersdorp Game Reserve and all that remains there are a few graves in the veld.

Grave in the veld

Born and raised in Krugersdorp, Jaco Mattheyse has deep roots in the region, with his family's history stretching back to the 1870s in the shadows of the Magaliesberg. A passionate History teacher at St Ursula's High School for over a decade, Jaco also serves as curator of the St Ursula's Museum, Art Gallery and Research Centre. His dedication to preserving local heritage extends to his role as co-founder of the Krugersdorp Heritage Association. Jaco's lifelong connection to the area fuels his commitment to documenting and sharing the rich history of his hometown.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.