Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The five historical buildings were built adjacent to one another over a period of about 50 years in the late 19th Century. Today they have been beautifully restored and equipped with authentic furniture and artifacts from the time of their occupation. Collectively known as the Paul Kruger Country House Museum, they are owned and curated by the Recreation Africa Group and are accessible to the public. The five historic buildings have each been awarded blue plaques.

The farm Boekenhoutfontein was bought by Paul Kruger in 1862 and he and his family lived there from 1873. After his death in 1904 the farm was divided between his two sons, Pieter and Jan, and his son-in-law Theunus Eloff; Pieter bought out his siblings’ shares in the early 20th Century. After his death, portions of the farm were sold off in subsequent years and the buildings were extensively altered and finally abandoned and allowed to fall into disrepair.

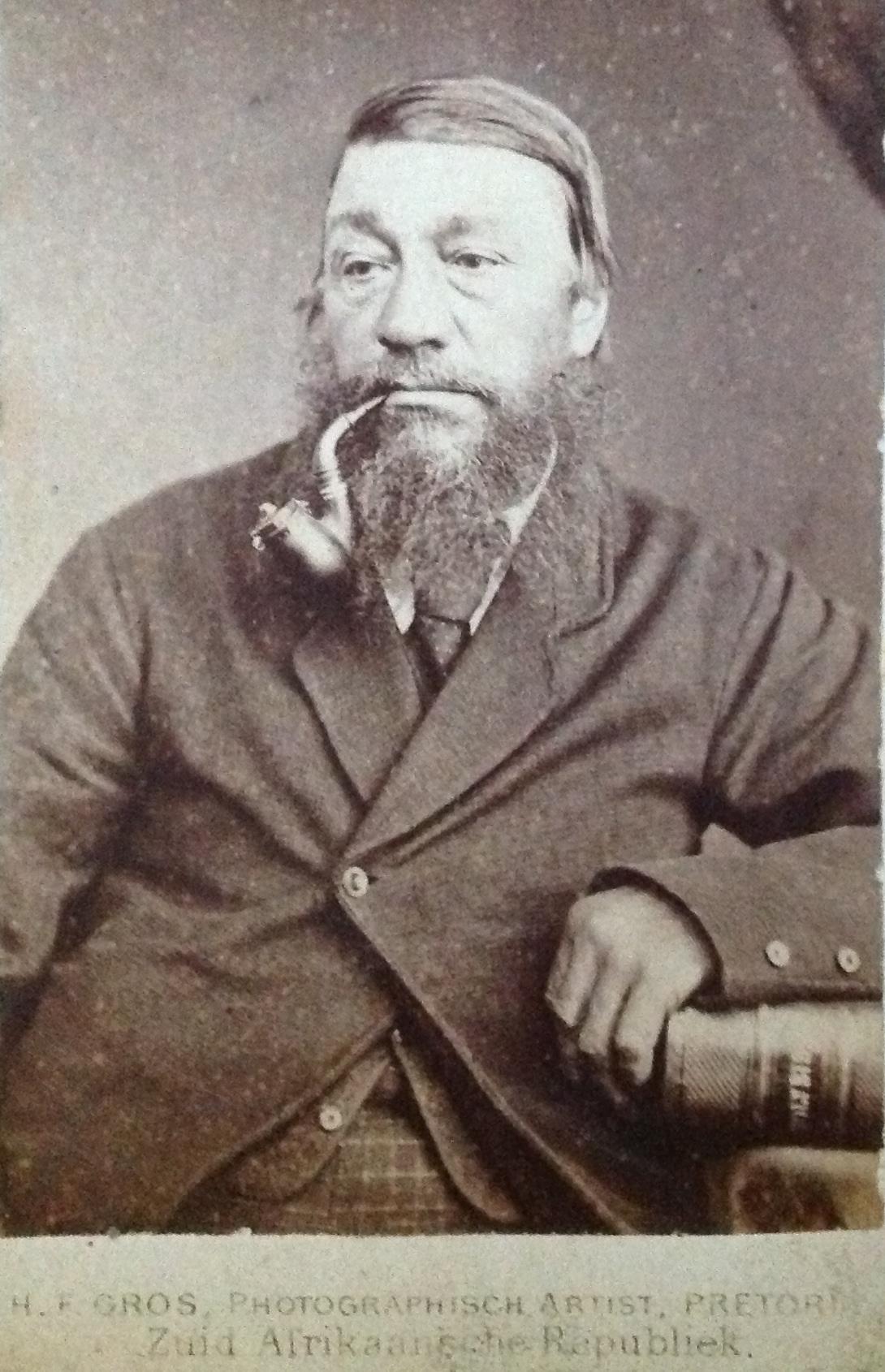

Paul Kruger circa 1876 (HF Gros via the Hardijzer Photographic Collection)

In 1971 the Simon van der Stel Foundation restored them to their original state and opened them to the public as a museum and restaurant in 1983. A decade later ownership of the historical farm passed to Recreation Africa Group, a private organisation with a strong commitment to the acquisition and preservation of southern African heritage. Kedar Heritage Lodge was built a short distance from the Kruger houses on the same farm and holds one of the most extensive collection of South African War artifacts and sculptures in private hands.

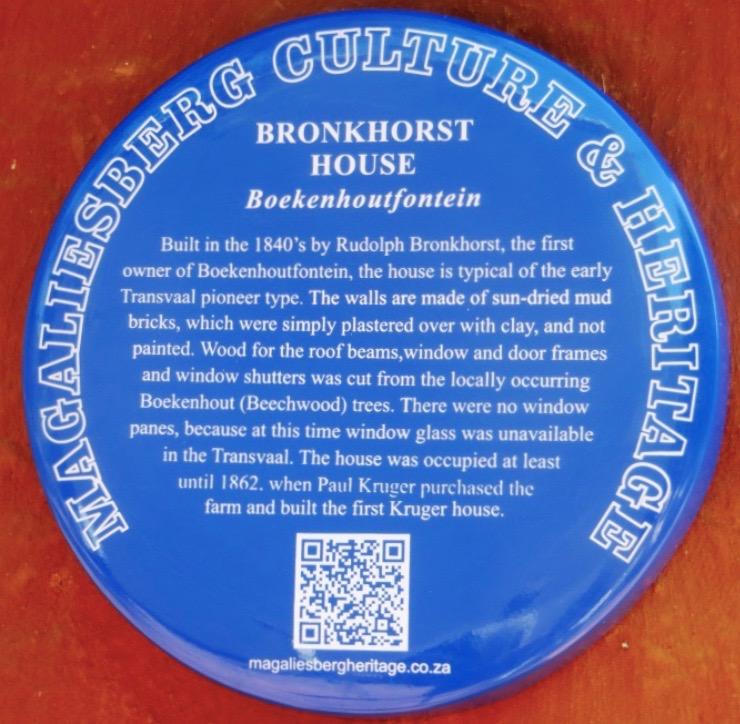

Bronkhorst House - The original house on Boekenhoutfontein before Paul Kruger bought it

In the early days of white settlement in the Transvaal, large tracts of land (usually between 3000ha and 4000ha) were allocated to all white adult male settlers. Title deeds for these allocated farms were formally registered for the first time in 1859. The farm Boekenhoutfontein was registered to Rudolph Bronkhorst, the original owner, at that time but it was immediately transferred to P.T Erasmus, indicating that the latter was already in possession. Kruger bought the farm and farmhouse from Erasmus in 1862, so the old house would have been built by him or by Bronkhorst between about 1840 and 1862. Traditionally it is known as the ‘Bronkhorst’ House.

The first house on Boekenhoutfontein built by Rudolf Bronkhorst or P.T. Erasmus from whom Paul Kruger bought the farm in 1862 (Vincent Carruthers)

The house is a simple structure, typical of the first homes built by migrant Voortrekker families when they settled permanently. Unpainted walls made from sun-baked mud bricks support a thatched roof. The original timber for roof beams, windows and door frames was cut from the local Boekenhout (Beechwood) trees, after which the farm was named. The widows are unglazed with wooden shutters. The interior comprised two rooms, one for sleeping and the other for living and eating with a large external oven on the west wall.

Paul Kruger was already a prominent figure in public life when he bought Boekenhoutfontein. He had been married twice (his first wife died of malaria two years after they were married). He was commandant the Rustenburg region and the following year he became Commandant-General of the Transvaal and a member of the Volksraad Executive Council. He had taken part in numerous battles against the local indigenous people and had become involved in the simmering confrontations among the Boers themselves, and he had played a leading role in the establishment of the Gereformeerde (Dopper) Kerk van Zuid Afrika, founded in Rustenburg in 1859.

He was also a significant landowner by the time he bought Boekenhoutfontein. It was one of the 27 farms (about 100,000ha) he eventually owned in the Rustenburg area. Nine of these he had been awarded to him in lieu of payment for military service, but others, like Boekenhoutfontein, were purchased from other landowners. It is unlikely that Kruger ever lived in the Bronkhorst farmhouse as he remained resident on another of his farms, Waterkloof, until much later. It was probably occupied by a bywoner or caretaker in the years after Kruger bought the farm.

Blue Plaque (Kathy Munro)

First Kruger House - Paul Kruger’s first home at Boekenhoutfontein

Soon after buying the farm Boekenhoutfontein, Kruger built a small house for his own use. It was similar in design to the Bronkhorst house, with simple accommodation and peach-pit floor. The house was built in the decade between 1863 and 1873 when the larger main house was erected.

Kruger’s first house on Boekenhoutfontein built between 1862 and 1872 (Vincent Carruthers)

Politically and personally that decade was a turbulent time in the life of Paul Kruger. Immediately after his appointment as Commandant-General in 1863, a Boer faction calling itself ‘the people’s army’ under Commandant J.W. Viljoen of Marico, rebelled against the presidency of Martinus Pretorius and, as head of the state army, Kruger found himself fighting in a minor civil war against some of his own people. The rift was reconciled in 1864 but a new problem to the north threatened to discredit Kruger. The Boer settlement at Schoemansdal was attacked by the Venda chief, Makhado, and Kruger’s punitive commando was unable to prevent the town being sacked by the Venda and abandoned.

At the same time he became deeply involved in the nefarious ‘inboekseling’ system whereby black children were kidnapped in raids on local communities and put to work as child labour on Boer farms – a thinly disguised form of slavery. Many of the child-trafficking raids were carried out on his behalf by the powerful Kgatla chief, Kgosi Kgamanyane, who had an uneasy submissive-cum-collaborative relationship with Kruger. Kgamanyane would bring captured children to Kruger at Boekenhoutfontein where, in his capacity as Commandant-General, he would allocate them among farmers in the district.

Kruger had acquired the Bakgatla and Bafokeng homelands as his own farms, Saulspoort and Kookfontein, and he demanded indentured labour as ‘rent’ from people living on their ancestral land. Boekenhoutfontein lay close to both of these tribal centres and was a useful base from which to conduct this activity.

A crisis arose in 1870 when the Volksraad legislated against unpaid indentured labour. Kgamanyane refused to continue supplying men as labourers and, in defiance of the legislation, Kruger had him publicly flogged by veldkornet Harklaas Malan. In protest, more than 10,000 BaKgatla migrated from the Rustenburg district to a new homeland at Mochudi in Bechuanaland. The exodus crippled the labour-dependant Boers farms around Rustenburg and Kruger faced a Volksraad commission of enquiry. He was eventually exonerated, but in 1871 Thomas Burgers was elected President of the Transvaal and his enlightened views were anathema to the conservative Kruger. He relinquished his position as Commandant General in 1873, moved his home to Boekenhoutfontein and temporarily withdrew from public life.

Blue Plaque (Kathy Munro)

Second (Main) Kruger House - The private home of President Paul Kruger until he went into exile in 1900

Paul Kruger was 48 years old when he built the main house at Boekenhoutfontein and moved into it with his family in 1873. The double-storey house is said to be based on the vernacular architecture found in the Cradock-Colesberg region where Kruger’s family were trekboers before joining Potgieter’s trek when Paul was eleven years old. Irrespective of its provenance, it was considerably more elegant than most rural dwellings in the Transvaal at the time. The rooms were spacious, the windows glazed, and a decorated staircase led to the upper floor in a land where double-storeyed houses were rare.

Main house at Boekenhoutfontein built by Paul Kruger in 1872-73 (Vincent Carruthers)

In the 1870s Kruger was implacably opposed to President Burgers’ liberal views on theology, education, and the economy, and had resigned from public life after a number of disagreements and political setbacks. However, he remained engaged in opposition politics from his home at Boekenhoutfontein, criticising the President’s policies at every opportunity.

His major opportunity came when the British annexed the Transvaal in 1877. The country was bankrupt, and Burgers was forced to accept the annexation and resign. The new British administration did little to endear itself to the local burgers. Kruger led the resistance which eventually resulted in the Boer victory in the First Anglo-Boer War of 1880/81 and the restoration of Boer independence in 1883. Boekenhoutfontein would have been pulsating with activity during that time.

Adjacent to Boekenhoutfontein was the farm Kookfontein which was also owned by Paul Kruger. On it lay the village of Phokeng, the ancestral home of the Bafokeng, and the people of Phokeng depended on Kookfontein for grazing and cultivation. Kgosi Mokgatle, chief of the Bafokeng, was therefore both Kruger’s neighbour and his tenant. The rapport between the two men was generally good and mutually respectful. However, during the 1880/81 war the relationship deteriorated when word reached Kruger that Mokgatle proposed assisting the British garrison besieged in Rustenburg. On the eve of the battle of Majuba, Kruger rode from Heidelberg where he was conducting the war and challenged the chief. Details of the confrontation differ slightly, but in essence Kruger attempted to assault Mokgatle whose men fell on Kruger and might have killed him had it not been for the intervention of the missionary, Ernst Penzorn, who was present. Days later the war was over with the Boers victorious and the friendship between Kruger and Mokgatle was repaired.

Kruger was elected President of the newly independent South African Republic in 1883 and two years later he left Boekenhoutfontein to live in Pretoria. The old farmstead remained his private home, however, and he visited it periodically until his exile in 1900.

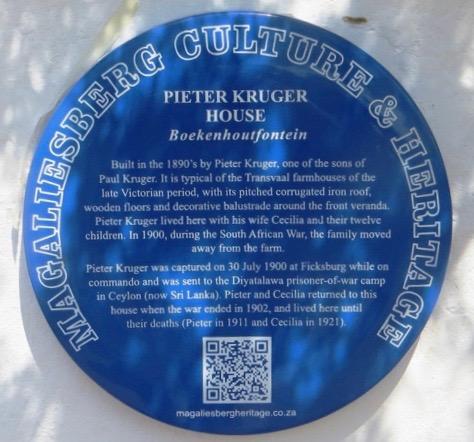

Pieter Kruger House - The home of Paul Kruger’s son, Pieter, who inherited Boekenhoutfontein from his father

When Paul Kruger became President of the South African Republic, he and his wife Gezina left Boekenhoutfontein to live in Pretoria. The capital was more than two day’s journey away and management of the farm from that distance was no longer practical, so his son Pieter took over the running of the Boekenhoutfontein. It is unclear when Pieter moved into one of the existing houses before building his own, but in the late 1890s he completed the fine late Victorian homestead now called the Pieter Kruger House. It is similar in architectural style to President Paul Kruger’s house in Church Street, Pretoria, with an elevated front veranda surrounded by a wooden balustrade. The corrugated iron pitched roof was characteristic of the late Victorian era and something of a luxury in the rural Transvaal.

Pieter Kruger's House at Boekenhoutfontein

In the 1980s, the Simon van der Stel Foundation used the house as the museum curator’s residence and the surrounding garden wall was built at that time to give some privacy; it was not part of the original Kruger house.

During the South African War (1899-1902) Pieter Kruger left the farm to serve on commando and his wife Cecilia and children moved into a house in Rustenburg. The house and several treasures, including the family Bible, were left in the care of the Bafokeng. It was a dark time for the occupants of Boekenhoutfontein. Pieter was captured in the Free State in June 1900 and sent to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as a prisoner-of-war. Two months later his aging father went into exile in Switzerland, never to return.

Soon after the start of the war, Kgosi Linchwe, chief of the Bakgatla, entered the war on the side of the British. His armies swept through the western Transvaal, plundered Boer farms and attacked Boer sympathisers such as the Bafokeng. Boekenhoutfontein was ransacked and temporarily occupied by Linchwe’s brother, Segale, who “took delicious pleasure in occupying Piet Kruger’s abandoned house and carting away symbols of Boer elegance such as a new pump organ”.

Pieter and Cecilia Kruger returned to the farm in 1903 to repair the damage and continue farming until his death in 1911 and hers in 1921.

Pieter Kruger House Boekenhoutfontein Blue Plaque (Kathy Munro)

Old School Room - The original farm school founded by Paul Kruger

The importance of farm schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth century is often under-rated. For many South Africans of that time, they offered the only education available. Farm children travelled long distances every day to be taught by dedicated, but often itinerant, men and women who were often the only literate people in the neighbourhood. Age groups were mixed, and lessons were juggled between younger and more advanced pupils to the best of the teachers’ abilities.

The School Room after renovation (Vincent Carruthers)

Little is known about the school room at Boekenhoutfontein. It was built during the years that Pieter Kruger lived at the farm and would certainly have catered for children from several farms in the area.

The structure is rudimentary. A single rectangular room with traditional packed clay floor. The roof is made of corrugated iron sheets, many of which have been beaten flat to cover a greater effective area.

Today the building has been fitted out as an information museum concentrating on the role of Black people and women in the South African war.

Blue Plaque (Kathy Munro)

You can view all the buildings and blue plaques by visiting Kedar Heritage Lodge. Click here for details.

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

Further Reading on the Kruger Houses

- Bergh, J.S., ‘Kruger and landownership in the Transvaal’, Historia 59(2), 2014: 69-78. - A comprehensive analysis of Paul Kruger’s acquisition of land in the Transvaal.

- Labuschagne, Elize, Boekenhoutfontein. Simon van der Stel Foundation, 1983 - An informative pamphlet published for visitors to Boekenhoutfontein after the restoration of the buildings.

- Kruger, S.P.J., The Memoirs of Paul Kruger. Toronto: George A Morang & Co., 1902. - Dictated by the author to H.C. Bredell and Piet Grobler, translated from Dutch into German by Rev. Dr. A Schowater and translated into English by A. Trixeira de Mattos.

- Mbenga, B. and Manson, A., ‘People of the Dew’: A history of the Bafokeng of Phokeng- Rustenburg Region, South Africa, from early times to 2000. Johannesburg: Jacana, 2010. - A detailed description of the relations between Paul Kruger and the Bafokeng. Meintjes, J., President Paul Kruger. London: Cassell, 1974.

- Morton, F., When Rustling became an Art: Pilane’s Kgatla and the Transvaal Frontier 1820- 1902. Cape Town: David Philip, 2009. - A detailed description of the relationship between Paul Kruger and the Bakgatla.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.