Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Before the discovery of gold in 1886, the Witwatersrand rang with the sound of sparkling springs, streams and waterfalls. These springs and streams are now hard to find as they have been put in pipes or canals under the city. Even if you can find the outfalls of these original springs and spruits (small streams), they are badly polluted. Sewage spills and uncollected rubbish, along with acid mine drainage and other chemical contamination, have put water quality into crisis in the heavily populated and industrialised Witwatersrand landscape.

It was of interest to me to find one of these hidden streams in the City and Suburban area of Johannesburg next to the N2 motorway. The current manifestation of this stream is a concrete and dressed stone canal and its toxic outflow. The quality of the emergent water is so bad that is must surely be emblematic of Johannesburg’s severe water pollution, decaying infrastructure and waste disposal challenges. Over a distance of about 2 km between a possible pristine ground water source to the north and the outflow, terrible contamination of the water occurs as it flows underground. This deadly-looking water flows south, untreated, into more natural river systems to become part of the Vaal system.

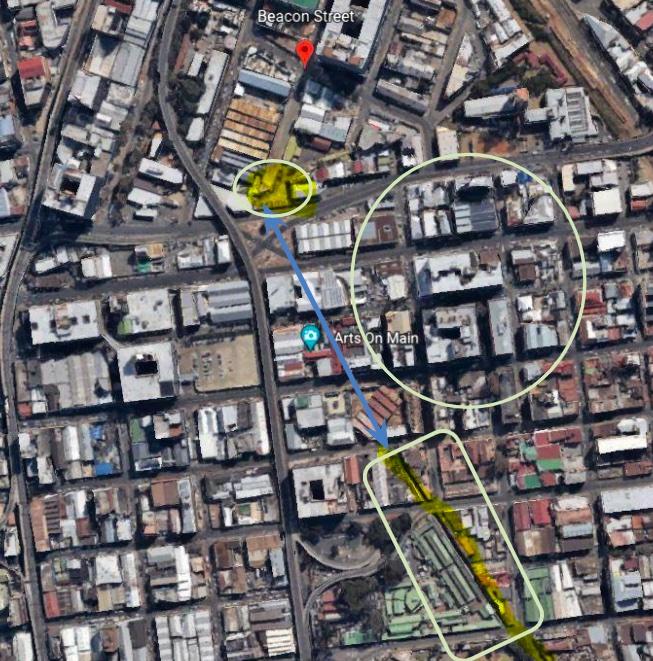

Between its hidden source and the outflow, there is an underground pipe and then an open air canal with four road bridges before the stream flows out into the open. One does have to wonder why there is a pipe in one section and a canal in another and what decisions were made about this. The way that the canal has been built between various buildings, including the Mai Mai market complex in this area suggests that it was there before or as the area was being developed. The Mai Mai complex is thought to have originally been stables and residential units in early Johannesburg, so being next to a stream would have been important. The Mai Mai complex was built after 1929 (as it does not appear on Holmden’s map of 1929), so potentially the canal must have also been built around this time because of the way it fits so closely to the Mai Mai complex (see image below). The canal system or any rivers in the urban areas also do not appear on Holmden’s map.

The open canal runs alongside the eastern boundary wall (wall and canal indicated by the blue oval) of the Mai Mai complex (green roofs), suggesting the two might have been constructed at the same time. (Google Earth 2022)

The Witwatersrand as a watershed

The Witwatersrand continental divide runs through Randfontein in the west, via the gold mining belt of Krugersdorp, along the Northcliff Ridge and Ontdekkers Road, through Braamfontein and Kensington, OR Tambo airport and the north of Benoni. Streams draining the Witwatersrand ridge to the south flow into the Vaal catchment, then into the Senqu–Orange system and out into the Atlantic. Rain that falls north of the Witwatersrand divide flows into the Indian Ocean via the Limpopo River system (GCRO 2017). Most of the Johannesburg CBD falls into the Vaal-Orange primary catchment system and thus any streams flow southwards.

The river systems of South Africa are in a critically polluted condition, contaminated by unmanaged sewage from both poorly-functioning urban sewage works and from direct sewage pollution from informal settlements without sanitation. Relentless urban development, agriculture, forestry, mining and industry have also contributed specific types of pollution over the years, with little effort to reprimand polluting sectors. Just plain old littering and dumping of domestic trash next to and into streams is also a big problem in urban areas. Even if not actually next to a water course, when it rains, this litter and any faecal material wash into drains and out into local rivers.

Litter dumped on the street at the back of the Mai Mai complex on Durban Street, City and Suburban. (Sue Taylor)

Finding one of Johannesburg’s hidden spruits

I have previously taken photos of this dismal road intersection at the corner of City and Suburban and Maritzburg Streets in Johannesburg and its bridge and canal, but this time I actually got out of my car. Parts of the Johannesburg CBD are definitely no-go areas for outsiders and this area is one of them. I was immediately surrounded by people wanting to know what I was doing, and even an unmarked police car (well, they said they were police) stopped to ask me if I was alright. Everyone was friendly. Locals I spoke to said that the spruit was part of the city’s storm water system, and that the water did not come from a spring, although I thought it may be both. No-one commented about the poor water quality.

The canal and its four road bridges are of no architectural value, other than some stone work. The canal outfall is not fenced and could be a hazard for pedestrians at night.

The exit point of the stream at the most southerly canal bridge at the corner of City and Suburban and Maritzburg Streets. There are two tunnels here, one either side of a concrete divide, presumably bringing water from two different sources. The left hand tunnel could be for storm water. The canal here is not fenced. This view is looking north. (Sue Taylor)

The sides of the canal made of dressed sandstone (Sue Taylor)

This water flows south out of the City and Suburban suburb and after travelling in pipes under the M3 motorway and the Kaserne railway yards, end ups in the Rocherville Dam (Rod MacKinnon, personal communication, 2023). The water is hardly flowing in January 2023, but presumably after a storm, this stream would be in full flood.

City and Suburban rich in mining history

This area is part of the original Central Rand goldfields and the locality of the City and Suburban gold mining company which was established in 1887, along with nearby Jubiliee, Salisbury, Jumpers and Wolhuter mines. The gold mines of the Central Rand, including City and Suburban, had all shut down by the late 1970s, including the City and Suburban mine. In the City and Suburban suburb now, there is no longer any trace of the City and Suburban mine, its buildings or its equipment, which is rather sad from a heritage perspective. Very few of the historical mining structures have been preserved or even documented in the past and a rich history has been destroyed (Fourie and Van der Walt (2006)). Only the slimes dams and polluted landscape remains, and even the slimes dams are disappearing, being reworked for residual gold.

Old postcard of City and Suburban Gold Mine

Currently, the main survivalist activity in City and Suburban Street is taxi washing and waste picking. A small informal settlement has sprung up around these activities. There is no municipal waste collection in this settlement. Other economic activities in the area include interactions with the many cash4scrap depots and waste buy-back centres, and working within vehicle chop-shops repurposing ‘written-off’ vehicles in premises behind high walls. The provision of cooked food and cold drinks to pedestrians and to the various business people like the taxi operators, taxi washers and the waste pickers is also important.

Trying to put a name to the spruit

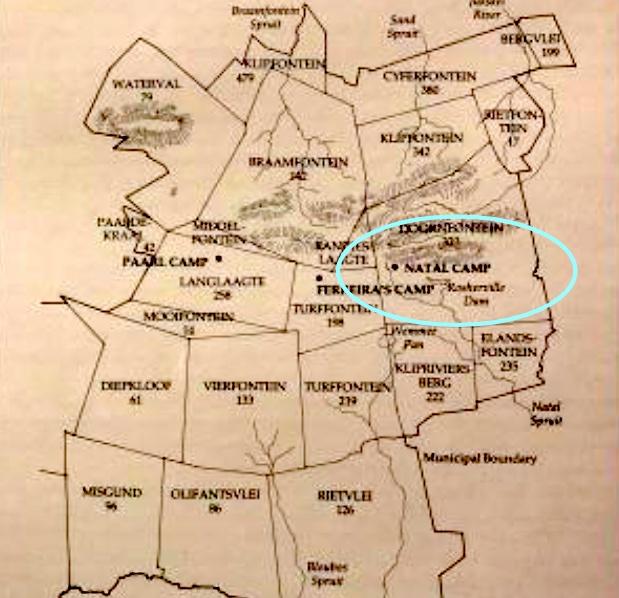

The early suburbs of Doornfontein, Fordsburg and Jeppe were declared around 1889 and on the periphery of these formal areas were the miners’ camps like Ferreira’s Camp and Natal Camp. So, although this stream appears ecologically dead now, a mere urban storm water drain full of sewage and trash, it once flowed in the open and the water quality was good enough for diggers to put up camp next to it around 1890.

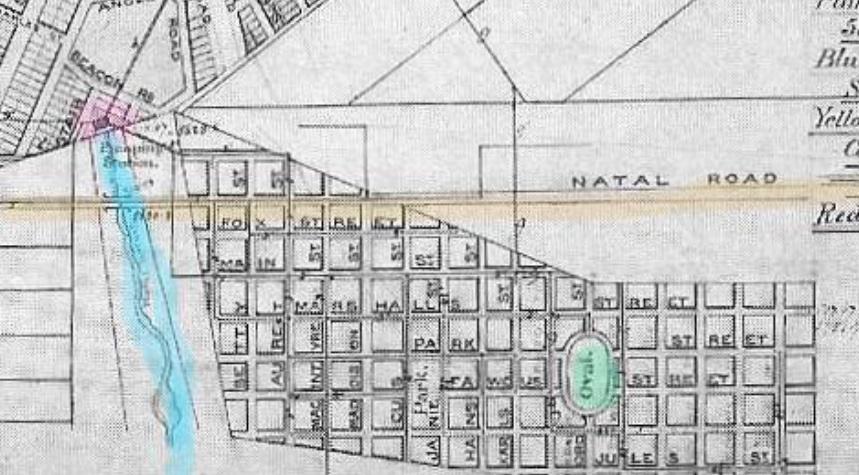

Section of the GR Andrews 1890 map of Johannesburg showing an unnamed stream (in blue) in relation to a Pumping Station (pink) near Beacon Street, the Jeppestown Oval (green) and the position of the Natal Road. This puts the spruit on this map in the proximity of the canal which we are trying to trace underground.

An article by WJP Carr published on The Heritage Portal (click here to view) mentions that the site of the Mai Mai market was “very close to the spot of the Natal Camp (first called Meyers Camp) where the diggers from Natal pitched their tents on the banks of the so-called Natal Spruit (now canalized).”

The Natal Road is indicated on the 1890 GR Andrews map above and the Natal Camp must have been on this road which was near Jeppestown. It makes sense that diggers would pitch a camp next to a stream. Natal Road eventually became Commissioner Street. Our hidden stream is likely to have been the Natal Spruit, as mentioned by Carr, although it might have a different name now.

The map below from the book, Johannesburg: One Hundred Years shows the locality of the Natal camp next to an un-named short stream. This is likely to be the short stream now canalised and emerging on the City and Suburban Road.

Early farms and original camps of Johannesburg, from the book, Johannesburg: One Hundred Years, but shown on the website Johannesburg 1912. The map shows the locality of the Natal Camp next to an un-named small stream that feeds into the bigger Natal Spruit in the south.

Google Earth was used to match contemporary streets and infrastructure to the Andrews 1890 and other maps.

This satellite image shows the possible location of the pumping station of 1890 (yellow shape) and the part of an old canal system currently still visible (yellow line) and that runs along the east side of the Mai Mai market (rows of diagonal green roofs). There must be an underground pipe (indicated by a blue line) that now connects the canal with the location of the pumping station (and possibly the actual source). The large yellow circle indicates the location of the Natal camp, based on the map of Johannesburg 1912 (Google Earth 2022).

Trying to glimpse the past

It is really difficult to try and imagine early Johannesburg, even though many photographs do exist, first of the original tented camps, and then small wood and iron shanties and the quick development of roads and a smart urban centre. These images cannot communicate the hardship and psychological stress that these hopeful men would have undergone.

The Natal Camp, a miners’ tented camp next to the so-called Natal Spruit stream in early Johannesburg, seems to have escaped photography. One can be certain that it was a most rudimentary and uncomfortable place, muddy and hot in summer, and freezing cold and dusty in winter. From existing photographs of early Johannesburg, it can be seen that the mining landscape was quickly stripped of any grassland vegetation. The few trees around rocky outcrops would have been used for firewood. Any game animals would have been killed for the pot.

Back then, there would have been no plastic sheeting and nylon ropes, or convenient Portaloos, for new encampments although corrugated iron did exist. It is likely that many fortune seekers may not have been able to afford any kind of material to make a decent shelter. These fortune seekers and their black workers would have lived in appalling conditions and been under-nourished, diseased, afflicted by ticks and other vermin, been subjected to violence in fights and work-related accidents, and also most likely, were heavy drinkers of cheap, low quality alcohol.

Early Johannesburg encampment (Museum Africa)

A freshwater canal reflecting Johannesburg’s early history

The springs and spruits of the Witwatersrand form part of Johannesburg’s environmental and natural heritage and they should be given much more protection, including rehabilitation so that they can provide fresh water as the city becomes more water-constrained. However, given the challenges facing the City of Johannesburg currently, this type of protection, both for mining heritage and water resources is unlikely.

From old maps, the origin of the short stream appears to be near Berea Street in the City and Suburban area because there was a pumping station there, as well as a stream indicated on the GR Andrews map of 1890. The locality of the stream in the Andrews 1890 map as well as in the Johannesburg 1912 map lines up with the locality of today’s stream. I am assuming that the original source of this water is where the pumping station was located. From the Heritage Portal article by Carr (2015), the spruit was called the Natal Spruit.

In my view, the ‘Natal Spruit’ canal system in City and Suburban, with its four road bridges, should be considered as heritage and should be afforded protection under the National Heritage Resources Act, with the site of the pumping station, the Natal Camp and the working of the City and Suburban Gold mine marked with signage to promote the remembrance of the importance of this area in the history of Johannesburg.

Points of comparison – Pretoria’s freshwater ‘eyes’

By comparison, the City of Tshwane (Pretoria) has been careful to protect the many freshwater springs that supply the city with drinking water. Approximately 57 million litres of water per day is supplied to the City of Tshwane from ground water sources (7.5 % of total requirements) and the remaining demands of 742 million litres per day is supplied from dams or nearby water boards.

Until the 1930s, two Fountains Valley springs (eyes) supplied all the drinking water to Pretoria (Dippennaar 2013). To ensure that these two springs continued to deliver quality fresh water eyes at a rate of 24 million and 18 million litres of water per day respectively, the Fountains Valley was formally protected as a nature reserve (Groenkloof Nature Reserve, declared by President Paul Kruger in 1895).

There are a number of other smaller springs like the Grootfontein spring which also supply Pretoria via various transfer schemes. In the case of the Grootfontein spring, the Rietvlei Nature Reserve provides protective zoning for this water source (Dippenaar 2013). The area surrounding the spring was proclaimed as a nature reserve in 1934. This means that no development is allowed around this structure. The difference between Pretoria and Johannesburg is of course, the environmental impact of the gold mining sector.

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. She is a development consultant with experience in researching, writing and lecturing about climate change and social/development issues in South Africa and Africa. She has worked in the biotechnology research sector, in nature conservation and in the NGO sector as a climate change activist, and more recently as a science writer. Her current interest is cities and urban climate change adaptation.

Dr Taylor is one of the editors of a new book on Phuthaditjhaba, QwaQwa, published in January 2023 and has also written one of the chapters, discussing greening as a way of climate preparedness for towns and cities. The book is now available with open access on https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-15773-8.

Sustainable Futures in Southern Africa’s Mountains: Multiple Perspectives on an Emerging City (2023). Editors: Andrea Membretti, Sue Jean Taylor, Jess L. Delves. Springer.

Sources

- Businesstech (2016). Joburg is 130 years old – this is what it looked like back then. Staff Writer.

- Carr WJP (2015). Mai Mai Market – ‘The Place of Healers’. Heritage Portal.

- Christie S (2021). Taking a tour of Gauteng’s dangerous drainage system. Sunday Times.

- Dippennaar MA (2013). Hydrogeological Heritage Overview: Pretoria’s fountains – arteries of life. A publication of the Water Research Commission of South Africa and the University of Pretoria.

- GCRO, 2017. Watershed boundaries of the GCR).

- Holmden’s 1929 map of Johannesburg. Johannesburg1912

- Krüger-Franck E (2019). Anthropocentric impacts on the ecology and biodiversity of the Natalspruit watercourse and its associated wetlands. MSc. Deptr. Of Environmental Science, UNISA.

- Munro K (2015). What did Johannesburg look like in 1889? Heritage Portal

- Snyman W (2021). A return to source: Saving the Witwatersrand’s ancient freshwater system to save South Africa’s rivers

- Tutu H, McCarthy TS and Cukrowska E (2008). The chemical characteristics of ac id mine drainage with particulars reference to sources, distribution and remediation: The Witwatersrand Basin, South Africa, a case study. Applied Geochemistry. 23(12) 3666-3684.:

- Fourie W and Van der Walt J (2006). Heritage Scoping assessment for the Top Star Dump mining project – Crown Gold Recoveries.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.