Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

If the question was asked what was the Crystal Palace? More than likely the answer would be an association football (soccer) team that plays in the English “Barclays Premier League”. If this was a pub quiz the answer would be correct and it would be next question please, however the more curious minded of us would wish to know how the football team got its name.

In the years before the Great War (1914-1918) the Final of the Football Association Challenge Cup (FA Cup) was held at a ground to the south of London known as the Crystal Palace Park. The owners of the ground wished for the stadium to be used as a regular venue, in order to tap into the crowd potential of the surrounding area and they raised a team, for the 1905-1906 season, to play in the Southern League’s second division, hence the name Crystal Palace F.C.

This now begs the question why was the ground called the Crystal Palace?

Between 1854 and 1936 there stood atop of Sydenham Hill a glass and iron edifice, which was a popular attraction for all walks of life - the Crystal Palace. It was erected as the main attraction to a park that had been laid out by the foremost gardener of his day - Joseph Paxton. For 82 years it had been a popular entertainment centre for both Londoners and visitors from further afield and had two railway stations (high level and low level) nearby, for easy access to and from the metropolis. Tragedy struck on 30th November 1936 when it was completely gutted by fire, an inferno which lit up the night sky and could be seen for miles around. Winston Churchill was to remark “This is the end of an age”; it was never to be rebuilt.

The structure which came to be known world wide as the Crystal Palace had a former life before its erection on Sydenham Hill, which had begun in Hyde Park. The year was 1851 and Great Britain, as the leading industrialised nation in the world, decided to show her pre-eminence by staging a Great Exhibition. The exhibition was scheduled to run for a period of six months from the beginning of May until the end of October and would be truly international with half the area of ground set aside for foreign displays. A plot of nineteen acres was marked out, but a huge difficulty arose in that not one of the plans put forward (and there were 240) were found to be acceptable by the Royal Commission, set up to run the show.

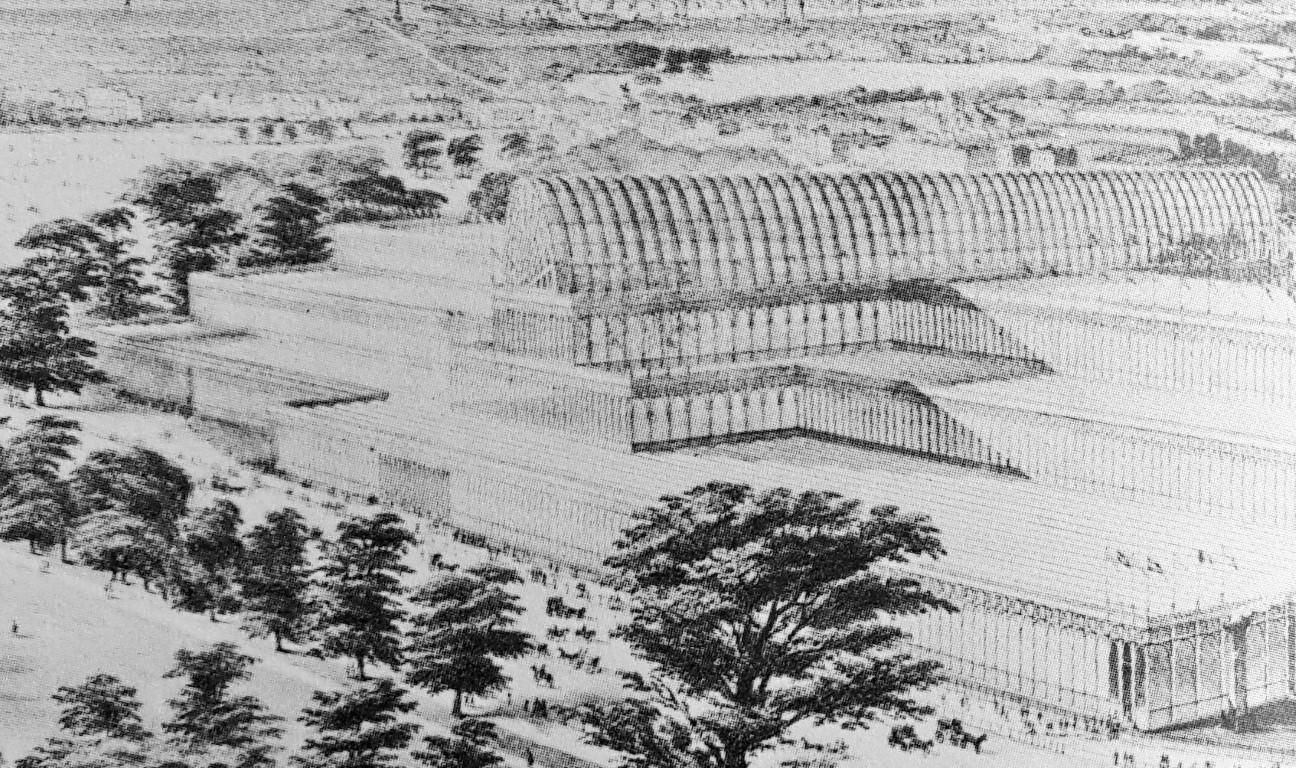

Part of the Crystal Palace from above (Victorian Engineering)

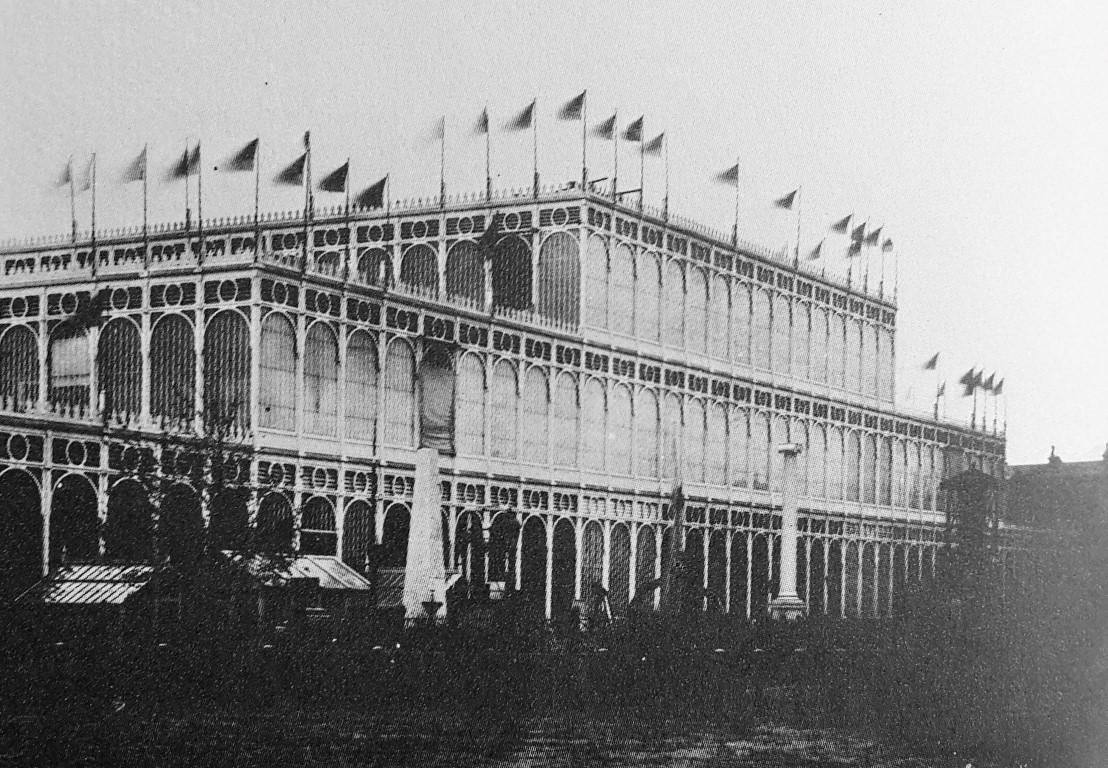

The west end of the building (Victorian Engineering)

Cometh the hour cometh the man and in the nick of time Joseph Paxton saved the day by designing what was a very very large greenhouse. Paxton was the head gardener at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, the stately home of William Cavendish, the sixth Duke of Devonshire, who was somewhat a horticulturist himself. Not only did Paxton have green fingers but he also had grey iron running through his veins and although he was of humble birth, he was a talented landscape gardener who had worked wonders at Chatsworth. There he had built a lily house for the exotic giant Amazonian water lily, which was given the name Victoria Regina. The leaves of the water lily grew to a span of six feet and could support the weight of a small child. This beautiful plant did not always flower in Europe, but Paxton was able to get one to bloom. His lily house was to become the prototype for the very much larger Crystal Palace in Hyde Park.

Paxton was introduced to Henry Cole the prime mover of the Exhibition who was keen for him to pursue a glass and iron structure, which was both easy to erect and dismantle. Both Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel gave practical advice, however the most important person to assist Paxton from an engineering standpoint was Charles Fox, who was a partner in the firm, Fox, Henderson & Co. the leading designers and fabricators of cast and wrought iron structures to the railway industry. Fox agreed to take on the structural design and fabrication of the exhibition building at a very low fee on the proviso that his firm could keep the component parts. Not only did Fox, Henderson & Co. supply all the iron parts – more than 2 000 prefabricated girders and nearly 400 roof trusses, but also they supervised the whole construction. Here we have a little South African interest in that the young William G. Brounger, who would later become the Chief Engineer of the Cape Government Railways, was tasked with supervising the work on the exhibition hall, of which he was highly praised in the contemporary Encyclopaedia of Architecture, which read “The symmetry and strength of this vast building depended upon the accuracy with which the simple plan was drawn and much credit is due to Mr. Brounger, who superintended the work”.

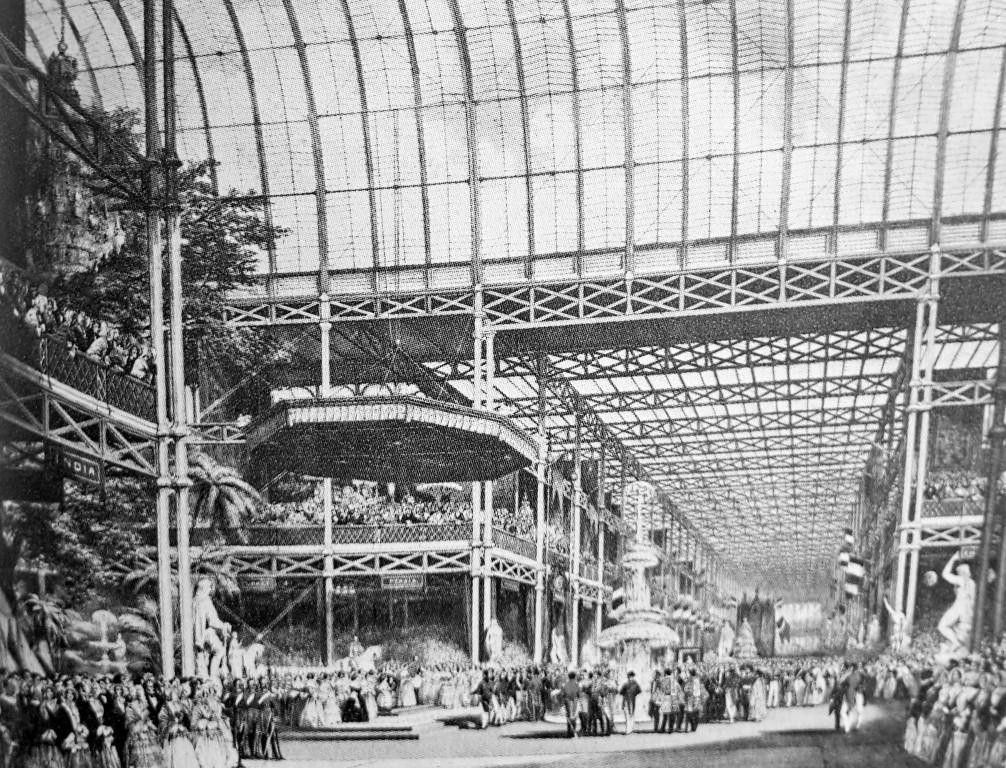

The design of the exhibition hall had to be revised on several occasions and so as to save felling some fine elm trees the original flat roof was altered to allow for a barrel vault transept, no mean feat as the trees were 135 feet (41.15m) high. When the 19 acres had been covered the interior was reckoned to be four times the volume of St. Paul’s Cathedral and yet it had been erected in only seven months at a low initial cost.

Inside the Crystal Palace (Victorian Engineering)

Queen Victoria and her consort Prince Albert officially opened the Great Exhibition at mid-day on the 1st May 1851, which was to be followed by the first ever royal walk about. The Prince was the Patron of the Exhibition and he was able to fully indulge his passion for science and culture, he was German after all.

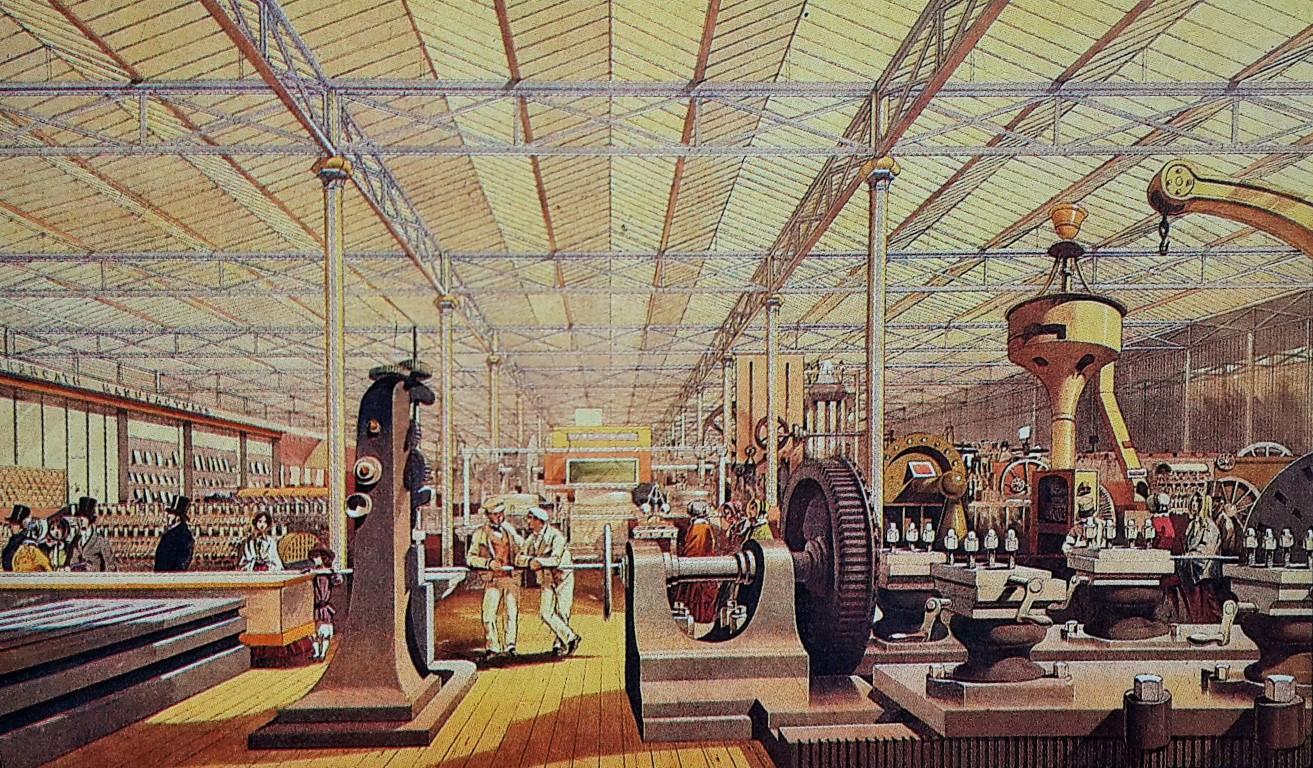

It was the satirical magazine, Punch which would give the glass and iron edifice its soubriquet “the Crystal Palace”, the palace of wonders and it was summed up nicely at the time, by a Frenchman, Michel Chevalier “It is elegant, simple, imposing and convenient; it is inundated with light and easy to approach. Every contingency has been provided against: rain cannot penetrate, nor fire can destroy. Steam was necessary to put in motion the numerous engines and machinery established in the mechanical division, for it was thought better to enable the public to see the machinery in motion; there are pipes which distribute steam where it is wanted, and vast boilers have been erected in an adjacent building, which afford an abundant and constant supply…. An electric telegraph is there to convey each moment to central bureau all communications that may be desired… When one reflects that all this has been conceived, adopted, moulded, cast, adjusted, placed and covered with glass in the space of a few months, we fancy ourselves to be in fairy-land. The Crystal Palace would have been an impossibility elsewhere than England” (from Ref 1).

Machinery exhibited at the Great Exhibition (Works of Man)

And there it stood in Hyde Park for the six month period of the exhibition, 3 800 tons of cast iron, 700 tons of wrought iron, 900 000 sq. ft of glass and 600 000 sq ft of wood; a great cathedral dedicated to the worship of material progress. It allowed six million people to enter, in all weathers, to see the advanced technology of the day, which thereby, it was hoped, would engender a better world with peace and harmony between nations.

References and Further Reading

- “The Industrial Revolutionaries – the making of the modern world 1776-1914” by Gavin Weigtman.

- “Architecture of the 19th Century” by Claude Mignot.

- “Structures - Man Made Wonders of the World” by Nigel Hawkes.

- “Victorian Engineering” by L.T.C (Tom) Rolt.

- “Girders in the Veld” by Eric Rosenthal.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.