Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Below is the first article in a series on the Brixton Cemetery by Kathy Munro. The piece begins by giving the reader a general understanding of the purpose, origin and meaning of cemeteries before delving into the history and significance of Brixton Cemetery. It finishes by highlighting the shocking current state of the cemetery and attempts by local groups to take action. Future articles will look at the epitaphs and symbolism of the Brixton Cemetery as well as stories behind the graves and family memorials.

Walker grave-site Brixton Cemetery (Kathy Munro)

Why the fascination of a cemetery? Cemeteries have always fascinated me. I love their tranquillity, remoteness and solitude. Stepping within the gates of a cemetery takes one into another world; it is the world of the dead but belongs to the living. Cemeteries are strange places as they are resting places for the dead, a means of disposing of a deceased body, but they are also places for the living to return to, to mourn, grieve and remember a loved one. I may not know any of the people buried there but immediately I become a vicarious mourner if only for an hour or two. Cemeteries are places to reflect on mortality, life, death, longevity and the possibility of an afterlife.

Cemetery definition. By definition a ”cemetery” is a place or ground set aside for burying the dead. The word derives from the Greek, κοιμητήριον, meaning "sleeping place". In the context of European cultures, the first cemeteries were the early Christian catacombs, then came the burials within church yards under church control. In Europe bodies were often buried in a mass grave until decomposed, then they were exhumed and stored in an ossuary in a church crypt or in the walls of a cemetery. Wealthier families had crypts and sand stones. Other cultures and societies had different end of life traditions: Egyptians believed in mummification; Hindus believe in cremation; Parses have a custom of erecting Towers of Silence, where their dead are left for the vultures and the whole body returns to nature; Buddhists believe in reincarnation and cremation, burial or embalming is acceptable.

Origins of the modern urban cemetery. More recently in Western societies choices lay between burial and cremation and, while modern cities have crematoria, burial never went out of fashion and accepted practice. Rapid population growth and urbanization in the 19th century led to the development of city cemeteries under municipal control rather than church management. Sometimes private companies developed cemeteries. The professional layout of these modern cemeteries owed much to John Loudon a landscape gardener and professional cemetery designer. London in this way developed Kensal Green in the 1830s and later came Highgate. Another example of an early landscape-style cemetery is Père Lachaise in Paris. It is a cemetery of 44 hectares or 110 acres and with 3.5 million visitors per annum it is the most visited cemetery in the world. Pere Lachaise is often featured in films about Paris. The graves of Oscar Wilde, playwright Moliere, the artist Géricault, musician Chopin, author Colette and even the more recent grave of Jim Morrison of the Doors (died 1971) are crowd pullers. In Paris, graves of the famous are honoured and protected.

The cemetery as a organized garden space. The very arrangement of cemeteries, with their formal avenues of trees, the geometric layout of sections divided by pathways that lead to family plots or remoter graves signals that cemeteries have a physicality and are organized places. These city cemeteries were rather like garden suburbs with care and attention paid to landscaping, paving, trees, paths and an orderly design in demarcated and even walled family plots. Modern specially created cemeteries were regarded as far more hygienic and sanitary for the living and the dead in modern cities. This was particularly important during epidemics and plagues when the speedy disposal of a body was imperative but the spike in mortality meant that mass burials could be resorted to. Disasters with high death rates could also give rise to emergency approaches.

A late afternoon view of Brixton cemetery (Kathy Munro)

A Vienna Cemetery. My favourite cemetery in Europe is the Central Cemetery or Zentrafriedhof on the outskirts of Vienna. It is a huge cemetery that dates back to the 1860s and is a place to teach history (I used to include the cemetery in Wits' student exchange programme). There is a Viennese joke that the Central Cemetery is "half the size of Zurich, but twice as much fun" (the cemetery is half as large as the city of Zurich!). It has a dead population of almost twice the present living residents of Vienna. There is a wonderful art nouveau church in the cemetery as well as a special section for great musicians. I am aware of the preservation efforts made by Vienna’s citizens where teams of gardeners and private citizens work to care for the cemetery. It was a private citizens' effort that restored the section with Jewish graves that were disgracefully desecrated during the Anschluss and Second World War.

Johannesburg cemetery origins - Braamfontein. Johannesburg, as a young city, set land aside for burying its dead from its date of origin in 1886. The first cemetery was located close to the centre of the nascent town, on the corner of Bree and Harrison Streets. Within two years a new cemetery in Braamfontein was established and the first burials there, date from 1888. The bodies from the first town cemetery were exhumed and removed to Braamfontein in 1897.

From the first, Johannesburg cemeteries also reflected religious as well as social identities. Divisions in life were perpetuated in death with different sections of the cemetery arranged according to different organized religions: Christians, Muslims, Jews, Chinese. Then the subdivisions multiply with the Christian section subdivided into for example, Dutch Reformed Church, Roman Catholic, Anglican (Church of England) or non-conformist church burials. Then there were the racial divisions: colour consciousness meant that racial divisions persisted in death with a separate section for the graves of African, Coloured and Chinese people in Brixton and Braamfontein cemeteries. Flo Bird, founder of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation, comments: “Remember, at Brixton we have the apartheid trench across the grave yard excluding the Chinese, Indians, Coloured and Black graves running up to the Hindu Crematorium”

Sarah Welham provided this information: "When the first Parsees starting dying in Johannesburg, they asked the Town Council for permission to erect a Tower of Silence but were refused; and so all Parsees dying in Johannesburg have to be buried. There must still be Parsees in Johannesburg as some of the graves are recent."

Managing old and new cemeteries. Today there are 35 cemeteries and two crematoria under the custodianship of Johannesburg City Parks. The City Parks website comments “as the city continues to develop and grow, so does the pressure on burial space and, in 2006, the City of Johannesburg set aside R20-million for the development of new cemeteries.” For me this raises even more questions: What is the future of old cemeteries? Should valuable urban grave yard space remain isolated, unused, remote and often neglected a century later? Should cemetery land not be recycled? How long should the dead in ancient graves be left undisturbed?

A cemetery with its well established trees, flowers, shrubs and often plentiful bird life is a green lung for the city but in the case of very old cemeteries, these green parks are seldom visited.

But is a cemetery not a heritage site? How can we bring people back to ancient cemeteries? An old cemetery is a site of heritage but what should a city do with a cemetery where three or four generations later, families cease to visit or maintain the graves. Where does the cemetery fit in the line-up of heritage responsibilities. I believe cemeteries should be preserved and visited to teach history in a way that brings the people of past generations back to life. Each cemetery has a story to tell. Flo Bird enthused: “I love visiting cemeteries, not mournfully at all. I see it as visiting and paying tribute where I am especially interested in them. The dead come alive when you remember them or they live on in memory.”

Graves disappearing beneath the ivy (Kathy Munro)

The History of Brixton Cemetery. The first burial in Brixton/New Cemetery was in 1910 as the Braamfontein Cemetery filled up and more space was needed. As early as 1905 it was reported that “Braamfontein would be fully occupied within 20 months” with 50 burials a week. Brixton is 84 acres and is located approximately one kilometre west of Braamfontein Cemetery. It was the principal Johannesburg cemetery until it reached capacity and was replaced by West Park Cemetery in 1942 (West Park lies beyond Marks Park and the Melville Koppies). However, Brixton comprises many family plots so people continued to be buried there even after West Park had been opened.

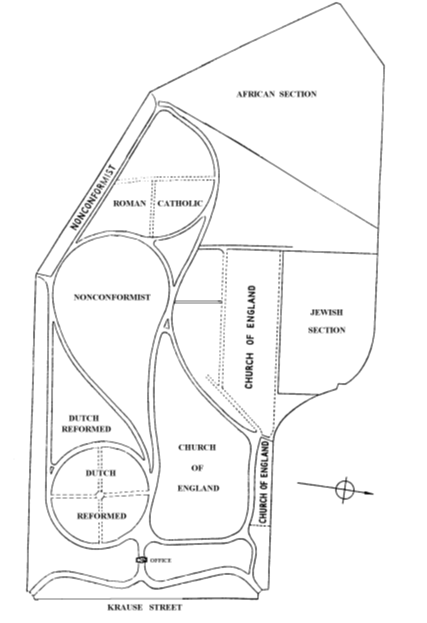

Cemetery layout

From the start, Brixton Cemetery was a landscaped, planned and organized cemetery in a park like setting with a design being of a “curviformed nature”, following the trend of English and Scottish urban cemeteries. The Council wanted a systematic layout and decided that inscriptions on the headstones would face the paths and walks so that they could easily be read. This was to be an improvement on what was seen as the confused state of Braamfontein Cemetery. The Council acceded to the request from the various religious denominations to have separate sections (Council Minutes, 18/03/ 1908, information sourced by Sarah Welham).

A family plot in Brixton Cemtery (Kathy Munro)

Brixton and the City’s history. Brixton Cemetery reveals a layered history of the city and its economy. Johannesburg had become a town of substance and permanence. The cemetery offers an insight into the city’s history, its gold mining past, its turbulent labour, union and worker conflicts arising out of the 1913 and 1922 strikes and the South African participation in two world wars. As the mining camp transformed into a sizeable town and then sophisticated city so too its cemetery reflected the kind of people who came to settle, lived out their lives, contributed to the city’s development, died and were buried here. There are many immigrant strands in Johannesburg’s demographic history - the Jewish immigration from Lithuania and Latvia, the English miners from Cornwall, Durham and Yorkshire, the thrusting Scots businessmen, the adventuring Irish, the German mining entrepreneurs, there was a Greek community, then the Italians, even the odd Australian or Canadian immigrant who died in Johannesburg would have been buried locally. Johannesburg people came from all over the world and mixed in were also the migrants from the towns and villages of South Africa. The late 19th century and early 20th century saw a state of demographic flux, the comings and goings of immigration and migration. Everyone was in search of his fortune; South Africa was a frontier country that promised game hunting, mining wealth or just perhaps an opportunity to make a better living than “at home”.

Choosing the burial plot for eternity. Where you were buried in the cemetery depended on other factors as well - class, race and religion determined location and the style of the design. Whether a tombstone is an elaborate one, a granite obelisk or a simple stone slab reveals the economic status of the family or person. A grave could be a space for a single person or a family plot with space for several family members, almost a mansion for the dead; some family plots having low enclosing walls. Sarah Welham comments: “Brixton is a manageable cemetery to see and understand as there is a time sequence in the layout of the graves.”

Who is buried in the Brixton cemetery? Here is an excellent way to engage with the city’s history. The names on graves become cues to research: who were these people in life, what did they achieve, who did they love or were loved by, when did they die, what was the cause of death? The questions push up through the decaying tombstones and around the creeping ivy. There are the graves and tombs of the so called Randlords and the toffs of the society, but there are also the memorials to the professors, the teachers, the musicians, the newspaper editors, the legal men, the pioneering woman in the girl guide movement, the architects and engineers, the business entrepreneurs and the doctors of the town. The diversity of the people buried at Brixton shows how by its jubilee, Johannesburg had become a city with a rich cultural, sporting, religious, community and education life that grew up around the fundamentals of the mining and commercial economy.

The Addition of the Hindu Crematorium. There is also a prominent and important Hindu presence at Brixton. In 1918, a wood-burning crematorium was built in the cemetery, on land organised by Mahatma Gandhi on behalf of the Hindu community. In 1912 the Johannesburg City Council allocated a piece of land 75 feet x 50 feet for the purpose of erecting a crematorium and by 1917 the size of the land had been increased to 150ft x 150 feet. The Hindu crematorium was declared a national monument in 1995. In 1957 a new gas fired crematorium was officially opened by the mayor of Johannesburg, Max Goodman (who was Jewish and is buried in the Jewish cemetery at West Park). It was built alongside the old crematorium and temple. You will find the Hindu crematorium on the Western Edge of the Brixton cemetery; I have explored that section on another visit and found the experience slightly terrifying as vicious dogs guarded and protected the crematorium and one could only view it from afar.

Brixton a place of landscaped beauty. Brixton is a beautiful cemetery as a site of heritage and history. It is a very traditional cemetery; there is a hidden and now little understood language of memorial signs and symbols. There is an architectural presence to this cemetery. Etched ivy, masonic tools, particular flowers, different types of crosses and institutional insignia convey meaning and belief. The headstones and tombstones reveal attitudes about the afterlife. The solidity of the stone work, whether granite or quartz or moulded concrete or sandstone provides evidence of a growing city’s prosperity.

Brixton is also important because it is a military cemetery. Many soldiers who fought and died in two world wars are either buried here (many were returning soldiers who then died of their wounds) or are remembered here by families who could not bury their sons where they fell in the North African Desert or on the Western Front of France. There is an iconic and internationally known Cross of Sacrifice here and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission takes an interest in this cemetery. There are regimental memorials here, for example the S African Scottish memorial and there have been enormous efforts on the part of the military authorities to restore the military graves.

Brixton and remembering mining history. Brixton is important because it tells the story of the City and South Africa’s mining industry and its labour strife. There are many who are buried here who were Rand Pioneers (men who had arrived in the mining camp prior to 1899). There is a modern memorial to migrant African Labour and indentured Chinese labourers. There are many graves that remind us that the life of a miner was likely to be short – you could either die in a mine accident, perhaps entombed underground or you could die of the dreaded miners’ industrial disease of silicosis. Many Johannesburg women were left widowed because of the voracious appetite for labour generated by the gold mines of the Witwatersrand. One of my party commented on many graves dating from 1919, and of course the reason for that was that the end of the first world war saw the international influenza pandemic that brought with it a high death toll.

Mortality trends in Brixton. It seemed to me that the earliest date of birth of anyone buried in the Brixton cemetery was circa 1860 and that whilst the average life expectancy might be between 40 to 50 years, there was the odd person who survived into his or her eighties or even nineties. It was your luck if you did survive to very old age but not such a happy fate for those whose children predeceased them and one often spots a grave that marks a child dying and grieving parents. Infant mortality was far higher than today and there are sections filled with small graves, the graves of young children. Families were far larger in the past, but it was rare for a family not to lose at least a couple of children to illnesses such as measles, diphtheria, mumps, or chickenpox; in a pre vaccination era childhood illnesses could be fatal.

Longevity, Youth and grieving parents (Kathy Munro)

A grand past, but a dismal present raises doubts about the future of Brixton. Brixton is a cemetery with a grand past but its future needs to be secured. Here is a cemetery in severe trouble. Brixton is a good place to observe that Johannesburg has problems with its current social dynamics and local governance. Visiting Brixton raises questions about tombs from the dead and homes for the living. I shall explain.

A rather grand tombstone and stone canopy complete with urns for the Hunt family (Kathy Munro)

The vagrants who live among the dead. Security is a concern when you visit Brixton. Our small photographic party was accompanied by a security guard; there was evidence of people living rough in the cemetery beneath bushes and under low hung branches, or nudging up against old tombstones. At the gate one man has created a home. There is evidence of human faeces in a few places, the ivy is overgrown and verges are untrimmed. The fence along Caroline Street has disappeared while funerary stone vases have been upended and turned into seating for braais. Bronze lettering on tombstones has been prized off and taken for recycling. There are many broken and damaged tombstones. Statuary of angels has fallen to the ground or if propped up repositioned on another grave. Monumental masonry has lost significant bits. Names on graves have disappeared. Everywhere there is litter and filth. Subsidence on some graves has not been attended to. In summary, here is a traditional mysterious old Johannesburg cemetery that has fallen into decay and total neglect. The result is that people can only visit in groups.

Lucille Davie reported as long ago as 2002 on the problems of Brixton cemetery: “Today (2002) Brixton Cemetery reflects a different kind of history - defacement and toppled headstones, mostly the work of vandals. Some graves have also experienced subsidence, causing headstones to fall over.” Now some 15 years later Brixton shows even worse neglect, decay and evidence of homeless people inhabiting the place. It has been an uphill battle for City Parks, Zoo and the Cemetery Department. Davie is to be complimented on the publication of her recent book that celebrates Johannesburg parks, the cemeteries and the zoo, but our cemetery is still in trouble.

Sadly, there is not much left of this family plot. This appears to have been the Kerse family area. They came from Gosport on Tyne

Flo Bird a woman who has made it her career to fight for Joburg’s heritage speaks fondly of this cemetery:

Brixton is a wonderful cemetery with a huge array of fascinating people ranging from Stafford Parker to Ken Birch and all laid out so beautifully. On my tour, I talk about the baronets as well as the workers. Sir William Dalrymple, Sir George Albu, Sir Lionel Phillips..… a little further on we get a mere knight Sir Frederick Spencer Lister. He actually deserved the title.

Johannesburg Heritage Foundation Tours. June is a perfect month to visit the Brixton Cemetery on a tour organized by the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation (led by Flo Bird, Sarah Welham and Gail Wilson). The tours are backed by detailed research, which draws on the documentation of Brixton Cemetery captured in the files of the JHF resource centre. Orange ribbons were tied around nearby trees to signal important graves to be viewed. It was a cold Highveld winter’s day with clear skies, and the pale warm sunlight casting shadows through the bare branches of trees. Winter is a melancholy time to visit a cemetery with fallen oak leaves, dried acorns and pine needles forming a soft carpet underfoot. I joined the photographic team led by Gail where we wandered in an undisciplined way and allowed the eye and a camera to capture the grave, perhaps a name or a particularly meaningful epitaph and the moment. A particular pleasure was a melancholic meander listening to the sweet, beautiful tenor voice of the muezzin calling people to prayers at the nearby neighbourhood mosque in Pageview/Feitas. I had never heard, in travels in Muslim countries, such beautiful melodious prayers. I felt a shiver of emotion.

The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation has at least three different routes for tours. One tour covers about a third of the cemetery. You need at least another two tours to get to the northern end which has historic graves of black, Indian, Chinese and so-called coloured people. Then there is the densely packed Jewish section to the East, now locked and fenced it is difficult to gain access.

The JHF tour started with my musings about transferred necropolitic nostalgia, “remembrance of thing past” and paying homage to the dead but shifted and became a journey of discovery to find the graves and the history of the prominent citizens of Johannesburg but also the presence of the ordinary man in the street, the lesser known citizens whose tombstones mark family remembrances to dearly loved and missed mothers and fathers, and where an immortality is achieved through the poignant epitaphs – such as “ thy willing hands toil no more” or the rhyming couplet recalls: “to a loyal heart, a spirit brave / a soul that is pure and sweet” .

City action needed to save Brixton. The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation has written to the authorities in the hope of action. Flo commented in a recent letter to City Parks and the Mayor of the City: “We have not done that section for a while because two years ago a gang came running chasing someone they thought had stolen a cell phone. This was somewhat intimidating so for the June 2017 tour we kept closer to the gates on Krause Street and 3 security guards accompanied us.“ Unfortunately Brixton Cemetery is being destroyed by homeless people, thugs and vagrants, who live here; there are no public conveniences so people the defecate behind trees and between graves. Tombstones are being wantonly destroyed, crosses smashed and delicate angels lie in fragments. We were particularly distressed by the destruction of the Webster family grave where the unique ceramic artwork has been smashed.

Example of a damaged graves, with upended crosses and another with a damaged plinth (Kathy Munro)

At the same time the dreadful condition of this aging and now neglected but extraordinary place led me to think about the future of the cemetery in our city. Should graves “belong” to a person or family in perpetuity? Should families be able to buy plots on a freehold basis? How can we make people care about dead strangers and why. Could Brixton and the even older Braamfontein Cemetery not become the Père Lachaise or the Highgate of Johannesburg? Could we get citizens of today to know about a particular story and get to the point of adopting a grave for preservation and upkeep.

Here is a solid rough-hewn granite Celtic cross marking the grave of John Wevell however, every scrap of bronze lettering on the tombstone has been prized off and lost. John was born in 1883 and “passed over“ in 1936. There are many such Celtic crosses in Brixton and these often indicate Presbyterian graves.

Flo Bird believes that Brixton Cemetery should be used for school and heritage tours, orienteering and bird watching while Sarah Welham is keen to start a Friends of the Braamfontein and Brixton Cemeteries. Welham highlights that members could work together in teams to restore gravestones that have fallen, trim trees that are interfering with graves and so much more. She knows that it will need a lot of negotiating with the City of Johannesburg because they are supposed to look after the vegetation in the cemeteries. I think this is a positive idea.

The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation Resource Centre has done an extraordinary job in documenting and photographing the graves of many people: it’s the well known, the not so famous but the person may have a beautiful headstone or an interesting inscription. A database has been compiled of all the people the JHF have noted/photographed in alphabetical order and in section order; in the different Johannesburg cemeteries (however not all graves are covered). If you are looking for someone specific and know roughly when they died, then the burial registers kept at Braamfontein cemetery office are the answer. The JHF maintains some major files of photographs. There is a charge for research access.

People need to come back to the cemetery and reclaim this public space. It is a green lung for the city as well as a place of remembrance and history.

In conclusion I wish to thank Flo Bird, Gail Wilson and Sarah Welham of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation for their dedication, friendship and capacity to share their Johannesburg on all of our adventures.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.