Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Known as “Long Toms”, the four 155mm siege guns installed in the forts to protect Pretoria, were supposed to be far too big and cumbersome to move, yet one of them (nicknamed Schanskop Tom), which had originally been installed at Fort Schanskop, was used to drive the British out of Dundee. It was manoeuvred up Impati Mountain and shelled the British camp on Ryley’s Hill. Unable to retaliate, the British were forced to withdraw from Dundee and make a hazardous, but mostly uncomfortable (in the pelting rain) retirement to Ladysmith.

H. Watkins-Pitchford, one of the Veterinary Officers stationed in Dundee, wrote to his wife that –

“The big gun of the enemy drove us out. They had managed to put one of their 40 pounders (6 inch) guns on a truck and had brought it from Pretoria on our railway, which had, of course, been left intact, with our usual disregard of our foe. This gun was mounted upon the top of a hill overlooking the town, and with it they poured in heavy shells at a range at which we were hopeless to reply as we had only light guns in our possession”.

This gun was subsequently moved to Pepworth Hill, just north of Ladysmith, as the Boers tightened their grip around the town. It came into action again during the abortive British sortie on 30 October, later to become known as “Mournful Monday”. Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes but at that time a Doctor serving with the British forces, wrote how –

“Huge shells – the largest that ever burst upon a battlefield – hurled from distances which were unattainable by our fifteen-pounders, enveloped our batteries in smoke and flame. One enormous Creusot gun on Pepworth Hill threw a 96 pound shell a distance of 4 miles … that terrible 96-pounder, serenely safe and out of range, was pumping its great projectiles into the masses of retiring troops”.

Towards the end of November 1899 the Boers decided to move the gun a little closer to Ladysmith, together with a 120 mm Krupp howitzer, onto Gun Hill at the foot of Lombard’s Kop. Its cousin, known as “Wonderboom Tom”, had previously been moved next door to Mbulawana Mountain on 8 November. The siting of these two guns within easy range of Ladysmith became a huge concern to the garrison. Civilians in town were forced to construct bunkers in their back yards or tunnel into the banks of the Klip River for protection.

According to Michael Davitt, after a few weeks of desultory bombardment of the town...

“During November the Boer laagers around Ladysmith attracted visitors of both sexes from the Transvaal; non-combatants who travelled down to witness the siege. The prowess of Long Tom, which was a legendary rather than actual, made the two guns on Lombard’s Kop and Bulwana objects of almost religious regard for the holiday seekers. Ladies by the hundred came from Johannesburg and Pretoria to enjoy the sensation of besieging an English army, and to experience the satisfaction of touching the big Creusot gun”.

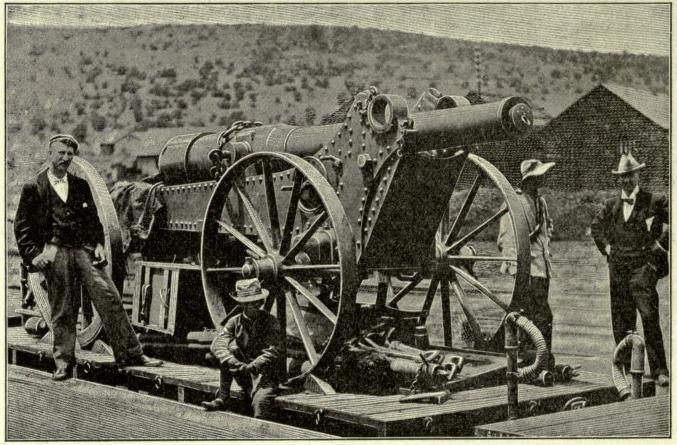

Long Tom Gun during the South African War (via Wikipedia)

Long Tom could engage a target by either direct (where the target could be seen) or indirect fire (where it could not, and a “spotter” had to be used). Since a shell will “drift” in the direction of the rifling in the barrel, target laying had to be adjusted and the gun laid slightly to the left of the target, to allow the shell to ”drift” to the right onto the target.

The gun’s angle of elevation was the angle that the barrel had to be raised or lowered in order for the shell to hit the target. The device used to measure elevation was known as a quadrant or field clinometer. The degree of elevation was firstly calculated, and result set on the quadrant. This device was then placed on the breech, and the barrel was then elevated or depressed until the bubble in the “spirit level” on the quadrant was level.

After six weeks of being subjected to enemy shellfire, the British had had enough and it was resolved to do something about the situation.

“On the night of the 7th. December, Major General Sir A. Hunter, K.C.B., D.S.O., made a sortie for the purpose of destroying the Boer guns on Gun Hill, which had been giving us much annoyance.

His force consisted of over 500 men with explosives and sledge hammers for destruction of the guns when captured”.

“The troops were led to their respective positions by Natal Guides, under Major David Henderson ... the guides had on more than one occasion carefully reconnoitred, by night, the whole area and, from the knowledge that they had gained, were most sanguine of success.

After the scheme of the sortie had been explained and all necessary instructions given, the men were led out under the personal guidance of Major Henderson, accompanied by one or two of the Guides. Night marching is difficult at the best of times, but this advance over broken ground, covered with thorn bush and cactus, through dongas and over boulders, was infinitely trying and a severe test of march discipline.

After what appeared an interminable scramble, the guides halted the assaulting columns at the points where, after deploying, they would commence their attack. It was now 2:30 a.m. Up above could be seen the crest line of Gun Hill, silhouetted black and hard against the starlit sky. The guides had done their share …

It was so dark, when climbing the almost perpendicular hill, that they were compelled to use their hands to feel the way and to haul themselves over the boulders. At last, when they had scrambled about a quarter of the way up, … yelling and firing broke out on the right; from above a volley of orders was shouted in Dutch, followed by a single shot and then a ragged rifle fire … the firing above increased in intensity and in consequence the advance was resumed with less speed and greater caution.

When nearing the crest line, Colonel Edwards was inspired to shout “Fix Bayonets” (the men had not a bayonet between them!). Evidently the defenders of the guns had no taste for cold steel (and) … they disappeared into the night.

Accurate guiding, possibly also a wonderful piece of good luck, brought the Colonel exactly to the spot of the big 6-inch Creusot gun (they also captured a 4.7 Howitzer and a machine gun). The men still further forward and placed them in extended order, where they lay down forming a covering party in case of counnter attack … it was a tremendous relief when two explosions in succession announced the fact that the guns had beaen rendered useless and the night’s adventure had been successful.

Major Karri Davies, to make doubly sure that the Creusot should not be used again, obtained leave to carry away its breech-block.

As (it) weighed nearly 180 lbs., its removal, considering the steepness of the hillside, was a tremendous undertaking. Although the ascent had been rough and extremely difficult, it was an easy task compared with the descent.

“The word to retire was given, and nearly every man brought away some souvenir of the fight. One had the tangent-scale of the gun, another the sights, a third the rammer; some had biltong; some tinned beef; even a tin of baking powder was among the trophies”.

As for Schanskop Tom, he was, so the British believed, mortally wounded during the affair. However, the Boers thought differently and he underwent extensive reconstructive surgery in the railway workshops in Pretoria. Schanskop Tom subsequently shyly reappeared in the field with a shortened barrel. He was inevitably nicknamed “Die Jude” or “The Jew”, because with its shorter barrel, it had obviously been circumcised.

The shortened barrel (via Wikipedia)

Main image: Long Tom replica at Fort Klapperkop (via Wikipedia)

Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. Since 1983 as curator, Pam McFadden has developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. As part of the museum collections she has collected and created an extensive museum archive, that holds many treasures.

Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.