Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The recent discovery in the cellar of a home in Saxonwold, Johannesburg of an old discoloured, brass plaque is a heritage opportunity and opens space for reviewing the motives and outcomes of the Royal Visit to South Africa in 1947.

The plaque commemorates the visit of the Royal Family to the Zoo Lake Sports Grounds on 5th April 1947. The current owner of the house does not know how the plaque came to be in the cellar of her home. She has generously passed the plaque on to the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation for preservation. The JHF has arranged for the professional restoration of the plaque by two of its members; it has been rebuffed and black enamel lettering repainted. A quality photograph will be taken and this will be presented to the Zoo Lake Sports Club, while the plaque will be presented to Museum Africa to become part of Johannesburg’s history. The Zoo Lake Sports Club’s website shows that it was renovated some years ago and it was possibly during that renovation that the plaque was discarded. It is time for a reappreciation.

This discovery has led me to delve into records of the 1947 Royal Visit. In 1947 the Royal Family (King George VI, his wife Queen Elizabeth and his two daughters, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret) undertook a leisurely three month journey (February to April) through their Southern African dominions (South Africa itself, Southern Rhodesia, Swaziland, Basutoland and the Bechuanaland Protectorate). The trip involved 10 000 miles of travel including 4920 miles by rail (though the family flew to Rhodesia). The journey to South Africa was by battle cruiser (the HMS Vanguard). It was a marathon endurance test in cheerful and gracious encounters with their African subjects; these were the moments of welcome, homage and delight. There must have been thousands of handshakes and platitudes exchanged that the people who met the King and Queen and the two princesses would remember the rest of their lives as “the day I met the Royal family”. Small girls curtseyed and presented bouquets of flowers (or in the case of Mary Oppenheimer a gift of diamonds from Kimberley was given). The occasions were many for cultural spectaculars whether Volkspele dancing or massed Zulu impis in warrior stance. Thousands flocked to the railway stations along the route for the brief whistlestop halts; these were the speedy moments for local dignitaries and guards of honour to be presented to royalty or to stand to attention for inspection.

HMS Vanguard in front of Table Mountain (via @tablemountainca)

A study of that Royal visit offers some insights into the politics of the day, social customs and history. I very much doubt that we would today go to the trouble of erecting an expensive brass commemorative plaque recording a royal visit. We are no longer monarchists, though we are once again part of the Commonwealth and the Queen is represented in South Africa by a High Commissioner and similarly a South African High Commissioner is the South African diplomatic representative in London.

Why did the Royal Family come to South Africa? It must have been a hugely expensive project and a logistical nightmare. I think the answer is because General Jan Smuts, who as Prime Minister extended the invitation, seemingly wanted to consolidate ties between South Africa and Britain. An additional reason could have been possibly to strengthen or maybe invent a South African national identity. Royalty was a particularly British institution and while there was ready resonance with the English speaking component of South Africa’s population, did royalty have the same meaning for Afrikaners, black Africans or South African Indians? What was Smuts thinking?

There was an election looming in 1948 and with hindsight, perhaps that Royal Visit was not such a smart political move. It is thought that Smuts’ closeness to the establishment during and after the Second World War was very much a factor in his electoral defeat just over a year later in May 1948, when the United Party was defeated by Malan and the Afrikaner Nationalists rose to power ushering in the long dark years of apartheid. The nationalists had very different ideas about social order, race and hierarchy and hence the coming of the apartheid state. The controversies of the day were the questions of human rights, race and segregation, the South African presence in South West Africa. The fascinating question is whether this Royal visit had negative consequences for South Africa and indeed there was some slippage between the issue of an invitation and the grand arrival in Cape Town.

What did the Royal visit achieve? In retrospect one can argue that it was a significant factor in costing Smuts and the United Party the 1948 election. But at the time it was seen as an opportunity to express good will and gratitude for the South African contribution to the Allied effort in the Second World War. Here was an opportunity to express patriotic feeling and monarchical fervour. We can argue that hereditary kingship was an essential glue that held the British Commonwealth and empire together. Could homage to King and Queen that symbolised those ties in wartime, not be extended into the peace time era. South Africa was a self-governing dominion but the King was the constitutional head of South Africa and one task was to open the 1947 session of the Union Parliament shortly after his arrival in Cape Town.

There’s an interesting article by Sarah Gertrude Millin (The Spectator, 19th June 1947). Millin was at that time a popular thinking author, an early admirer and biographer of Smuts. She wrote:

What, then, did the visit achieve? Principally it showed the physical possibility of a closer Union between the Dominions and England and one another. The King of England was quite simply opening the South African Parliament in his capacity as the King of South Africa. It may indeed have set going the conference system, an important accomplishment that would be. It sweetened the atmosphere of South Africa. Here came four Royal people from England - and they were not at all like the King's grandfather with his goodwill tours in Paris. They were modest, lovable, so anxious to please, so eagerly pleased, that it was almost painful to watch them doing their duty, and another duty, and still another duty, and a further duty, and anything anyone considered a duty - more, indeed, than was necessary for duty.

It is interesting that Millin puts her finger on the personal appearance of the couple; that they were affable, modest, pleasing and easily pleased, carrying out their duties with dedication and commitment. They were a model King and Queen for a democratic age but with an empire trailing behind. It was an empire transitioning towards independence in the wake of the Second World War but with a future less clear at the time. Who better to make that transition than a modest second son king with a stammer and his slightly plump but feisty Scottish queen. The glamour factor was there too; the queen and her daughters must have required an entire train coach to convey their wardrobe. They wore light colours, pastel shades, beautiful hats (the Queen's were often adorned with those floating ostrich feathers from Oudshoorn) long white gloves, stylist forties peep toe shoes, neat handbags and of course magnificent jewellery. The King on the other hand dressed for the occasion whether in uniform, business suit, robes of state or nifty knee length shorts for the safari moments. The paparazzi had not yet come of age but official photographers, newsreel cameramen and journalists did dutiful duty. It was all so consciously but rather low key in stylish demeanour; the late forties fashion signalled a Britain coming out of war time austerity with dress designers such as Norman Hartnell (who designed the Queen’s Wedding dress later the same year) making do and being inventive. The Royal Tour of South Africa was the first post war peace time celebration of empire and an African perambulation. There were all the many photo moments and there must be thousands of photographs of the entire vist. In turn too, the King carried a camera to photograph the game of the Kruger Park and whatever other moments took his eye.

The Economist in an article in May of 1947, reflecting on the significance of the Royal Visit in the context of “a divided dominion” and the political as they saw it of the three big racial divides. Between the planning of the Royal visit and the actual commencement, South Africa had been criticised severely at the fledgling United Nations because of its attitude to South West Africa and to Indian civil rights at home. Among the Afikaner Nationalists, republicanism was also in the air. Malan was already airing his views about “apartheid” (a word not yet in the dictionary), but while some political leaders boycotted and made their disapproval known, royal charm, official pomp and circumstance and warm South African hospitality meant that the tour was a triumph for fashion, memory making, personal good will and harmony. The Economist article pontificated then as much as it does today, warning that a move towards the nationalists (it was already seen that the election could be won by Malan) could sacrifice South Africa’s international stature and status. Prophetic words indeed.

The Royal party arrived in Cape Town by battleship cruiser, the HMS Vanguard in Cape Town on February 17th. The Vanguard was the pride of the Royal Navy, it was the largest, fastest, newest battleship of its day, built during World War II but only commissioned after the war. The Vanguard served between 1946 and 1960 and cost over 11.5 million pounds. On this 1947 visit it carried a staff complement (officers and crew) of 1 975 men. Below is an impressive photo of the Royal Family with the crew. It strikes one as somewhat excessive and extravagant that nearly 2000 naval personnel were required to care for the four royals.

The Royal Family and the Crew of the Vanguard.

The South African Railways published a substantial (red hardcover) souvenir book in anticipation of these Royal travels; complete with maps, colour plates (birds, flowers, wild life), and sepia toned photographs. It set out the planned itinerary and gave a romanticised view of history, sites and scenes to be encountered en route. Many such souvenirs were produced in 1947; most popular and still to be found are the medallions (given to school children and dignitaries) and commemorative mugs (not too difficult to find either). Pathe news reported on the Royal Visit and today you can find these adoring, patriotic news reels on You Tube. It was a well recorded visit with everyone armed with Brownie Box cameras lining the city streets to catch a glimpse of imperial grandeur.

Commemorative Medallion

South Africa’s Coat of Arms in 1947 reflecting the four provinces: Cape, Natal, Orange Free State and the Transvaal

In 1947 South Africa had two official languages, English and Afrikaans. It also had two official national anthems, one was God Save the King while the other was Die Stem (written by the poet C. J. Langenhoven in 1918 and was set to music by the Reverend Marthinus Lourens de Villiers in 1921). This was the arrangement between 1938 and 1957 when Die Stem became the sole national anthem until 1994.

Princess Elizabeth, as she was then, celebrated her 21st birthday (21st April, 1926) in South Africa. For her it was a momentous year; a year of the great South African adventure, coming of age, then her engagement followed by marriage to Prince Philip. During the tour she had her first solo public engagement, the opening of the Princess Elizabeth graving dock in East London. Her sister Princess Margaret played second fiddle, though she was often seen as the prettier, more fun loving daughter.

This year, as the reigning Queen Elizabeth, she celebrated her 90th birthday. Her mother, who had a long innings as the Queen Mother, lived to the grand old age of 101 and died in 2002 as did Princess Margaret, but she was 71. The present Queen’s reign of over 60 years has been feted and celebrated, though such has been the change in political structures and climate that the diamond jubilee and the 90th birthday hardly mattered in South Africa. Queen Elizabeth is still queen of the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and some 12 island nations but many of the former British empire dominions have seized independence. Of course the Queen is still head of the Commonwealth, but in South Africa’s case there was the intervening history of withdrawal from the Commonwealth and then readmission after 1994. As a ruling monarch the Queen has surpassed the reign of her great grandmother, Queen Victoria.

Today, when royals travel abroad, the trips are shorter and the photo moments are many and eagerly sought by photographer and royal. Plus the dreaded paparazzi look for the unguarded moments. Prince William and his wife Kate, as Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and their two children, made a one week, intensely packed tour of Canada in September 2016. It seems far more informal though hardly more relaxed than back in 1947. Queen Elizabeth in support of reconciliation and the new government visited South Africa only again in 1995 (19-25 March), when she was met by 50 people at the airport and then made a short helicopter flip to Simons Town to spend a night on the royal yacht, Britannia. It was only a 6 day speedy tour of the main centres. The queen addressed the new Parliament, following the 1994 all race election with universal franchise. Mandela had become our “rainbow nation“ President. In 1999 the Queen returned to South Africa for the 16th Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting that took place in Durban. She came for exactly a week between 9–15 November. Thabo Mbeki was the President.

Looking back on the specifics of the Royal Visit of 1947 reminds us, how much South Africa has changed in 60 years. The past is indeed another country. In 1947 South Africa still had General Jan Smuts as Prime Minister and the country was a dominion within the British empire having made its contribution to that empire on the side of Britain and her allies in the Second World War. Soldiers who volunteered, enlisted and fought with determination in North Africa and in Italy were now being thanked for their contribution. In 1947 there was an aura of post war patriotic fervour. Most white English South Africans were royalists, almost by birth if not by political conviction. It is interesting that Indian South African political opinion was split and the Natal Indian Congress boycotted the Royal visit in the context of discrimination against “Asiatics” at that date. Gandhi in India supported the position. African decolonization did not come until the 1960s.

What of this Royal Visit? Prime Minister Smuts took huge pride and pleasure being the gallant personal host of the Royal Family. His political responsibilities must have taken second place for many weeks when he was in attendance. He escorted the Royal family up Table Mountain and to the Royal Natal National Park. His wife, Isie Smuts did not accompany him or the Royal Family but they came on a visit to meet Ouma Smuts at Doornklooof. South Africa went to great lengths to commemorate the visit in the medallions mentioned above as well as in special issue stamps.

The Royal Family at Doornkloof in 1947, visiting Ouma Smuts.

Special issue stamps

The itinerary was by White train and was hectic, with train station views of towns such as George, Oudtshoorn, Graaff-Reinet, Grahamstown, Umtata, Aliwal North. Larger centres must have put on more substantial receptions and banquets – a day in Bloemfontein, East London, Port Elizabeth. Game reserves came high on the agenda. Towns prepared and printed welcome programmes and agendas for receptions, and these are now most collectible items of royal memorabilia. The Natal National Park gave them a welcome weekend break and thereafter the Park became the Royal Natal National Park; today the hotel stands in ruins but it used to show off its royal suite and I can remember in the 1970s thinking we had moved into the upper classes to be allocated the royal bedroom (it was actually quite ordinary and hospitable in a homely way, having once been a hostel for hikers).

The Royal Train 1947

Royal Natal National Park Hotel in ruins (The Heritage Portal)

The Royals in South Africa were given the most royal red carpet welcomes. They saw the best of the country as well as some rather curious places – game reserves, wine farms, the Port Elizabeth Snake Park, the East London graving dock, clipping ostrich feathers in Oudshoorn, an official banquet in Pretoria, the award of an Honorary degree to Queen Elizabeth at UCT (towards the end of the visit – that colonial connection that featured quite prominently on the UCT history section of its website until recently), the vistas of Drakensberg at Mont aux Sources.

The awarding of an honorary degree (UCT)

The brass plaque Sports Club visit reminds us that there were the large and the small occasions and events. I have followed up on the programme for 5th April 1947. I gather that there must have been some changes in the programme as the official Railways programme allocated only 1 day, 2nd April, to all of Johannesburg, the East and the West Rand and the following day they were supposed to be in Pietersburg followed by a weekend in Pretoria. How did it then happen that Saturday, 5th April saw the Royal family in Johannesburg for a programme that included a visit to the Crown Mines (photographs show them wearing hard hats and protective waterproof coats for the underground descent), a visit to Baragwanath Military Hospital and the conferring of awards to various World War Two military heroes. At Baragwanath a red carpet was laid out and some rare photos from the Arnott collection show the informality and delight of those who were honoured. Then too came the visit to the Zoo Lake Sports Grounds. The Thelma Gutsche book A Very Smart Medal also shows the visit of the Royal Family to the Rand Easter Show, and there is also footage on a Pathe news clip.

Visit to Baragwanath Military Hospital

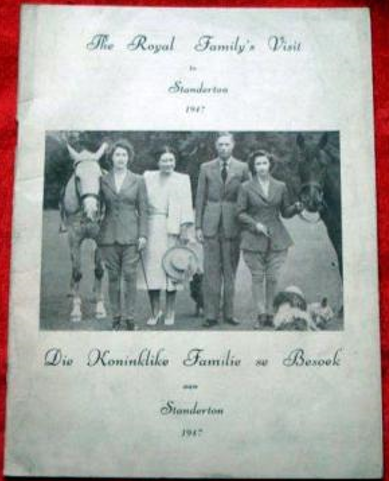

There was a celebratory ball at the Johannesburg City Hall, with young women attired in gorgeous evening gowns forming a tableau to represent the Heart of Africa. Fireworks and bonfires blazed from the golden mine dumps and lit the almost lunar landscape of Johannesburg. The Royal family visited the Turfontein Race Course to see the running of the Kings Cup. There was a ceremony at the Cenotaph with the King unveiling an inscription to the fallen soldiers of World War II. There was a visit to the Benoni Town Hall, the Krugerdorp Town Hall and a garden party in Pretoria. At Standerton there was an open air banquet and a display of Volkspele dancing (they were there from 12h45 to 15h30!). It must have been an endless succession of dinners, presentations and group displays. There was more Volkspele dancing in Pietersburg. The Princesses and Queen were given diamonds in Kimberley, all presumably added to their personal collection and not the state crown jewels.

Visit to the Kimberley Diamond Mines – 18th April Friday. Princess Elizabeth inspecting graded diamonds.

Standerton Programme Cover

Gerald Smith in a report for the Adelaide Advertiser 3rd April 1947 (an Australian digitized newspaper found on line) - tells us of the anticipated visit of the Royal Family to Crown Mines on the 5th - and I was amused that the entire report was written in advance of the actual descent down the Crown Mines shaft to 8500 feet. The Mine visit was recorded as a private visit added on to the itinery. During his visit to Johannesburg (the largest city in the Union), despite being of short duration, the Royal Family “saw more people in one day - and more saw them - than on any day of the tour. It was well over a million, black, white, and khaki.” By all accounts it was a marvellous three months for the Royal Family, and the occasion was forever remembered by those who met them.

Reported in the Chicago Daily Tribune 19 April 1947 Princess Elizabeth was presented with a 6 carat perfect blue and white diamond and Princess Margaret received a 4.5 carat stone gift from the Oppenheimers (presented by Mary Oppenheimer). The Union government’s 21st birthday gift to Princess Elizabeth were 87 more diamonds suitable for setting in a necklace – 21 major stones totalling 71.31carats.

Here is a strange addendum to my zoom in on the 1947 visit. In 1947 in late March following a severe icy winter, flooding on the Thames followed the thaw of ice sheets. Surprisingly and with open generosity South Africans collected funds for British flood relief. These were called the Great Floods of 1947 and the flooding of the Thames was the worst 20th Century flood of the River Thames. Canada too sent food parcels to Britain. The Royal Family did not cut short their South African sojourn but flood relief for Britain was a popular charity in South Africa. Back in 1947 we were not an underdeveloped country but had the sources to send gifts and donations to struggling Britain. Its all in perception!

If anyone can provide me with a copy of the programme of the Johannesburg visit of the Royal family this would add greatly to this contribution.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.