Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Midge Carter’s fascinating account of the behind-the-scenes goings on during the making of the movie “Zulu Dawn” (provided by Pam MacFadden and published on 26 August 2021 - click here to read), brought back many memories, some of which can be safely shared with a respectable journal such as The Heritage Portal.

Zulu Dawn movie poster

Pietermaritzburg did not know where to put itself in 1978 while “Zulu Dawn” was being filmed in and around the city. Everybody was agog with excitement and the Natal Witness produced breathless pieces about sightings of the likes of Peter O’Toole, Burt Lancaster, Sir John Mills, Denholm Elliot, Simon Ward, etc. Male students on the local campus of the University of Natal volunteered en masse to appear as extras and as British soldiers. The most cursory military accomplishments during national service were polished up to resemble heroism at the Battle of Alamein, or the drill proficiency of the Grenadier Guards. Those who knew one end of a horse from the other, such as Mooi River farmers’ sons at the agriculture faculty, were not only in high demand by the film producers, but they swaggered around the pubs as though they were the Household Cavalry in Whitehall.

Burt Lancaster (as Colonel Anthony Durnford) and Peter O’Toole as Lord Chelmsford on the lawn of San Souci Mansion, the location for the signing of the ultimatum scene.

I was a very junior archivist at the old Natal Archives Depot at the time and, when these exotic movie researchers appeared to consult documents, we were totally overawed. They sniffed at the historic maps in the Map Collection, and it was only then that I discovered that colonial Natal had been very poorly mapped before the Anglo-Zulu War. During the campaign there was a surge of map making that tailed off afterwards until the Anglo-Boer War when the dearth of maps once again hampered British military operations.

But what the researchers wanted to see were samples of Lord Chelmsford’s and Sir Bartle Frere’s handwriting. We found some examples in the Government House Collection, which contained the correspondence of the governors of Natal. Then came a specific request: Did we have the actual ultimatum that the British presented to the Zulu delegates on the banks of the Thukela River? Miraculously, we did. Then the query: “May we borrow it?”

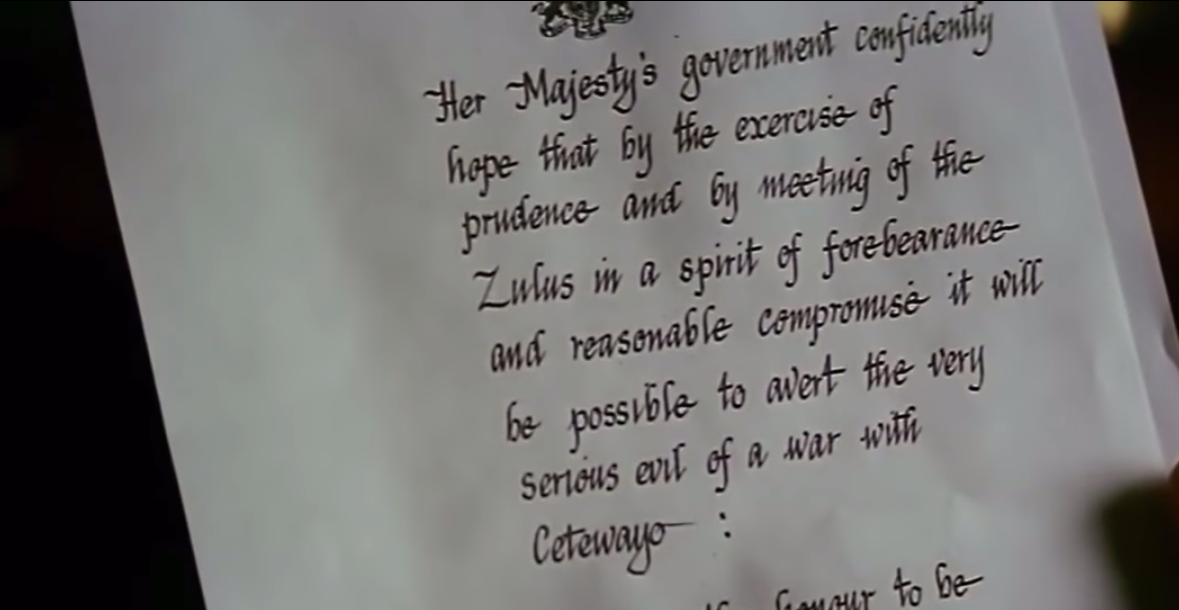

Crash, the irresistible force of dazzling movie requirements met the immoveable obstacle of official archives regulations: back then original documents were not to be loaned out at all. I can’t remember which of us archivists came up with the solution, it could have been the result of a teatime brainstorming session. The Government House collection had been handsomely restored and rebound and, in the process, many blank pages of the original stationery had been placed in storage. We could photocopy the ultimatum (which had been written in black ink) on to the original foolscap-size blue, watermarked, paper. It would look completely authentic in a camera shot. Pretoria had to be consulted, but we got a cautious and somewhat puzzled approval.

The Ultimatum Document in Zulu Dawn

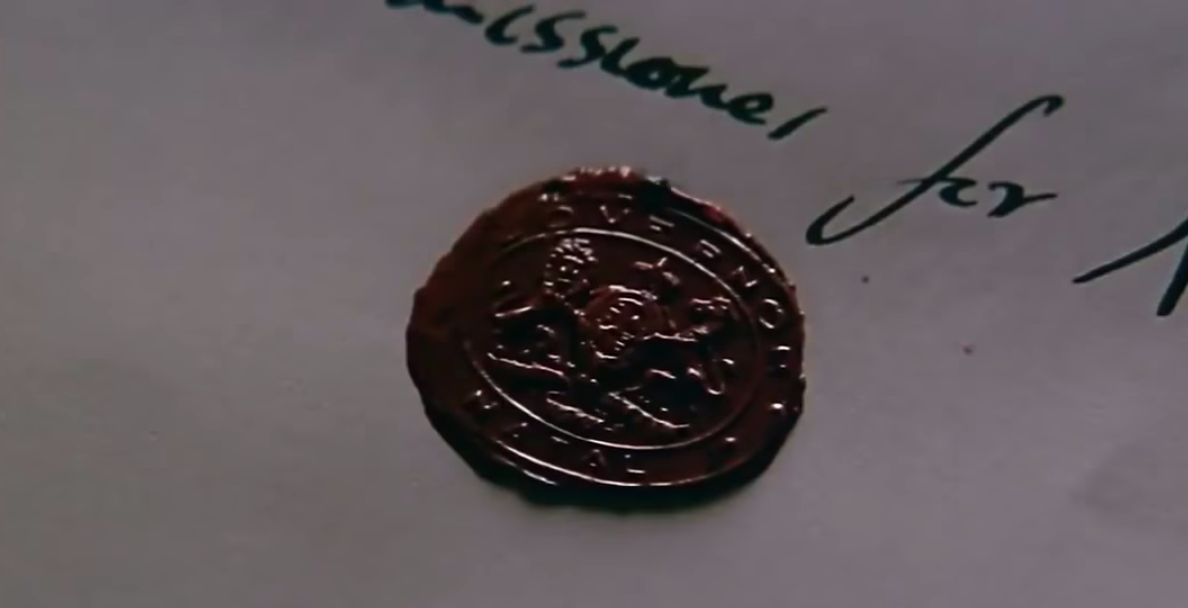

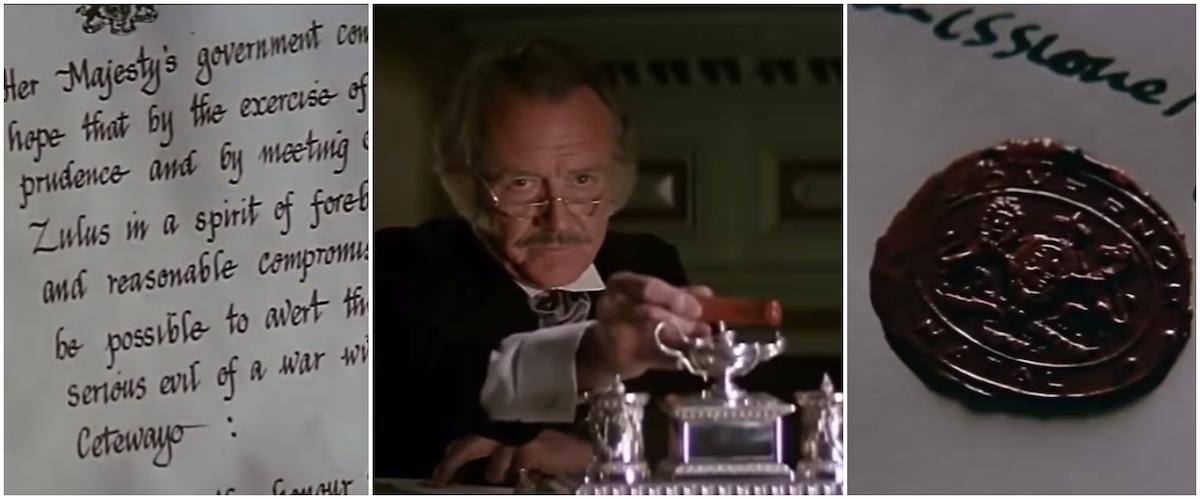

We set to work with a will and the researchers and special effects people were delighted with the results. Then the ante was upped even more. Sir John Mills, playing High Commissioner Sir Bartle Frere, had to place an official seal in red wax on the ultimatum document. Could we oblige?

We had our tails up with a following wind by this stage and, yes, of course we could. The official seal of the Colony of Natal was held at the Archives and we found a stub of government issue red sealing wax, which, in the 1970s, was still the same as that used in the 1870s. It was swiftly written off in the assets register as an “expired comestible product”. Then the official seal posed a conundrum: It was not actually part of the official archives, but it was government property (even if the colonial government no longer existed). The solution was for the seal to be loaned out, but it should always be within sight of a government official. The Chief Archivist was not interested in the film, but we youngsters were detailed to guard the seal with our lives. This meant we got passes on to the set and locations of “Zulu Dawn”.

The red sealing wax used in Zulu Dawn

A pass on to the set of “Zulu Dawn” in Pietermaritzburg in 1978 was pure gold and we made the most of it. I had to meet John Mills and Peter O’Toole and explain the significance of the ultimatum paper and the colonial seal to them. John Mills grasped it quickly and with great charm. O’Toole required much liquid refreshment to keep him hydrated in the dry Pietermaritzburg winter, although this never affected his diction. However, he also shrugged his agreement.

When I spoke to the two great actors, they were on location in Alexandra Park at the city’s Victorian cricket oval. The magnificent Indian Raj-style pavilion building had been imaginatively tarted up as the British army headquarters. The real headquarters of the Victorian era was Fort Napier, in use as a mental hospital in the 1970s and thus inaccessible to film crews. Waving the pass, I was able to swan through the layers of security into the stars’ caravans. If I remember correctly, Midge Carter arranged this. I did not witness O’Toole falling of his horse, but I did witness the scene where he was on his horse talking to another mounted officer. What the photo Midge published did not show, were two men kneeling in front of the horses, firmly holding the reins. Perhaps lessons had been learned.

The Victorian Cricket Pavilion at the Oval in Alexandra Park, Pietermaritzburg. It morphed into the British military headquarters for the shooting of “Zulu Dawn”

The scene with O'Toole on his horse talking to another mounted officer

It was early evening as I left the Oval and on the edge of its heavily guarded perimeter, was a large stand of azaleas, flowers for which Maritzburg was famous. These rustled as I passed and the head of the professor of English at the local university poked out. He was trying to sneak in with his children to get in on the action. When I called out a cheery “Hello Prof”, guards appeared from all directions and the professor was frogmarched away with his wailing family. He glared daggers at me as he passed, and I was very glad that I was no longer one of his students.

The location used for the signing of the ultimatum was a very grand Victorian mansion called San Souci, which represented the governor’s residence for the purposes of the film. Most rooms led off the spacious verandah and I was ordered to stand on the verandah, out of the way of the cameramen, trying to peak in to see the sacred seal on Sir Bartle Frere’s desk. Sir John Mills, as Frere, signed the photocopied ultimatum on its authentic blue paper with a flourish and dripped the archives sealing wax on to the document. The Seal of the Colony of Natal was wielded for the first time since 1910. At this, alas, my official duties and the film set permit expired. Fortunately, I did manage to get into a couple of the parties!

Sans Souci (SAHRIS)

“Zulu Dawn” was filmed during the era of the cultural boycott and there was some controversy about the appearance of British actors on South African soil. I also remember that while there was a great premiere in the old Twentieth Century movie house in Maritzburg, the film did not remain on circuit for long as there was some controversy over the rights. The producers also ran into financial problems and the Natal Witness reported that many local service providers were out of pocket. Certainly, it was never the hit with British audiences that “Zulu” was and still is. But it has a devoted following among the Anglo-Zulu War buffs. It may be out of copyright now which is why it is available on modern social media. If you see it, watch out for the photocopied ultimatum and the stamping of the document with the seal.

The seal in Zulu Dawn

By the way, the Wikipedia article about the movie is full of inaccuracies, readers beware!

Dr Graham Dominy is a former National Archivist of South Africa and is also an historian and author. He currently serves as a member of the National Heritage Council, but he writes in his personal capacity and these views are not necessarily those of the National Heritage Council.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.