Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

My primary interest as a photo historian is in historical South African photographs from before 1915, but photographs from before the 1960s are not totally excluded from my research interest.

Most images curated in the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC) are, therefore, more than 65 years old with some as old as 175 years.

So, often I walk into a charity store asking for old photographs. A comment I receive all too often is: “We discard them due to the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA).” or “We recycle them based on legal opinion received.”

Another disturbing comment, although not relevant to this article, is: “We discard them in that there is no interest/value in old photographs.” One charity worker recently added: “You are the only person ever to have enquired about photographs.”

Although I reluctantly accept that there may possibly be some validity in these views by charity organisations, the destruction of photographs cannot be applied as a blanket approach to all photographs donated.

The reliance on the law to justify the destruction of historical images is, therefore, absolute nonsense and largely ill-guided. Charity organisations that take this stance, willingly and knowingly partake in the destruction of South African heritage, possibly important artifacts.

The ongoing and “wilful” destruction of photographs due to the law allegedly being prescriptive around this irks me, resulting in me researching this aspect to better understand these arguments.

It needs to be said upfront that I am not a legal practitioner. Should any of the facts presented below be incorrect, I would appreciate input accordingly. This will be in the best interest of curating historical photographs optimally instead of allowing them to be destroyed on an ongoing basis.

On a philosophical note – At a recent photographic symposium, I asked the question to a like-minded person whether it would be possible to actuarily figure out the number of historical photographs destroyed annually contributing to the loss of South African photographic heritage. The response I received was: “What does it matter – work with what you have.”

So true - there is no shortage of historical imagery – I have my research work cut out for me for the rest of my life with the material available. I also need to add that, as a purist I only work with original photographs and although reproductions or images used in publications do occasionally aid my research, these are not curated in the HPRC.

The point remains – There simply are too many valuable images being destroyed in South Africa and although I do see an uptake on social media in the reliance on old photographs amongst local genealogists, town historians etc., the general apathy towards original historical photographs amongst South Africans remains - as a society, we hold little interest in our visual history.

This article includes a broad range of photographs ranging from between 1878 and the 1950s to support the argument around their potential value to researchers. The photographs were randomly selected from the vast Hardijzer Photograph Research Collection. It is argued that each of these photographs hold their own unique heritage value. The primary interest in my research work is to identify the studio photographer where possible. Where there is no professional photographer information contained in the photograph, the next level of importance becomes the sitter (from a genealogical perspective), followed by themed photographs. Most black and white snapshot photographs do not contain the amateur photographer’s information, resulting in the focus falling on the themed photograph. Themed photographs include, amongst others, architecture, occupations, airplanes, old cars, military, pets, toys, railways, motorbikes, and humour. It is the destruction of these images that needs to be halted.

A Cabinet Card with little provenance. The details of the family of 12 and the photographer are unknown. This is sad in that this is one of the most unusual and beautiful studio compositions of a large family. The key question is: Is the heritage value of this photograph (circa 1905) reduced because it has no provenance? Not at all – Other than the unique composition, the photograph tells a story of creativity in the photographic studio as well as a story of the larger families during Victorian times.

This black and white snapshot of the wreck of the Nightingale near Port Shepstone was captured in 1947. The photograph was captured 14 years after the 137-ton fishing trawler/cargo ship (a steam vessel) ran aground on the rocks off Glenmore Beach in 1933. Even if the person in the photograph was known, there are no legal restrictions in using the photograph.

Cute – Probably a young actor (circa 1910) by an unknown photographer. This image may become significant when researching early theatre productions and the role children played in them. Who knows – if an actor, by placing this image, the young chap may soon be identified.

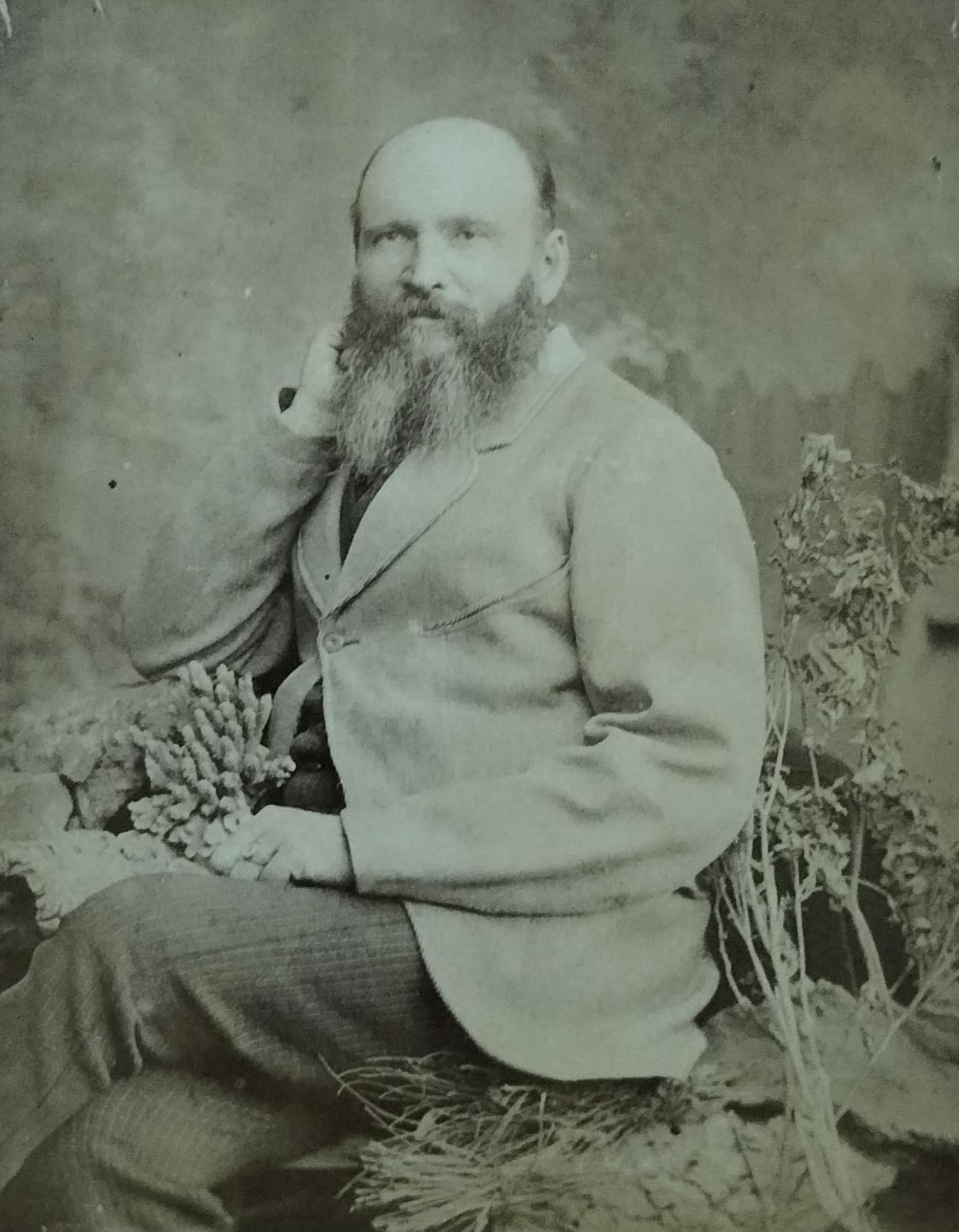

Another “rescued” photograph. Why even consider discarding this unique heritage-related photograph? A Cabinet Card photograph by Grahamstown-based photographer CJ Aldham (circa 1878) of South African-born George Samuel Wood (1828 – 1884). Of significance of this photograph is that Wood was the first appointed mayor of Grahamstown. He was also a member of the MLA (Member of Legislative Assembly).

High achiever with much silver around. Who is he and what were the accolades for? Sport? Cabinet format photograph by an unknown photographer (circa 1905). The photograph remains unique in that it deviates from the stock-standard “dull” studio poses. Hopefully, by placing this photograph, a reader may make a link. Given the unique studio backdrop, ongoing research may also eventually identify the studio in which the photograph was captured.

A cornerstone of a building was unveiled by two ladies in 1910 (One being Mrs. W. Richie). The clergymen surrounding the ladies suggest that this was a church being built. Somewhere a church historian may identify and confirm the location of where the photograph was captured as well as the denomination (Catholic?). There are two photographers at work at this significant event. Note the shade of the second photographer falling on the lady standing on the left. Also, note the Boy Scout standing on the left.

Only two South African laws pertain directly to photography or the photograph. They are:

1) Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA)

A photograph of someone is the property of that person, just like any other of their personal information would belong to them. If someone is recognised from a photograph it’s considered their personal data. Photographs of people still alive, therefore, carry personal protection.

Personal protection certainly no longer applies to those who have passed away. We hold legal rights as living beings. An example of a personal right is the right to privacy. But once we die, we are no longer a legal personality. This results in the rights attached to our legal personality, like privacy, falling away. This then also applies to data privacy laws like POPIA which only apply to living humans and juristic persons.

In short, the protection in these laws does not extend to the dead. So once our life ends, our privacy rights end as well.

I do accept that as lay people, charity workers will not be able to determine whether the people in the photographs are still alive or not. The next challenge is that charity organisations also do not know how to date photographs, so the safer option for them is to rather destroy the potential artifacts.

There are, however, exceptions to the use or sale of photographs of a living human being (as it relates to POPIA and a photograph):

- Obtaining consent from the subject.

- Public vs Private space – there is no reasonable expectation of privacy for photographs taken in public space, yet the converse applies to photographs captured in a private space.

- In commercial use, a consent agreement will typically be needed.

- Commissioned photographs are owned by the client and not the photographer (negotiation dependent).

Although the dead cannot hold rights, the next of kin or other stakeholders may have confidentiality and privacy rights – it is, however, doubtful whether POPIA will protect the next of kin as it relates to a photograph.

Most critical in considering the above is that the Protection of Personal Information Act was only promulgated in South Africa in 2013. The intention of the act was also not to be applied retrospectively. In other words, the argument that photographs from before 2013 are protected by this act is incorrect. The act therefore only applies from post-2013 and most certainly not to photographs from before 2013.

In using photographs of people who have passed away, post-mortem privacy may need to be considered. This entails respecting the wishes of the dead person or the family. One source suggests that the dead also need legal protection.

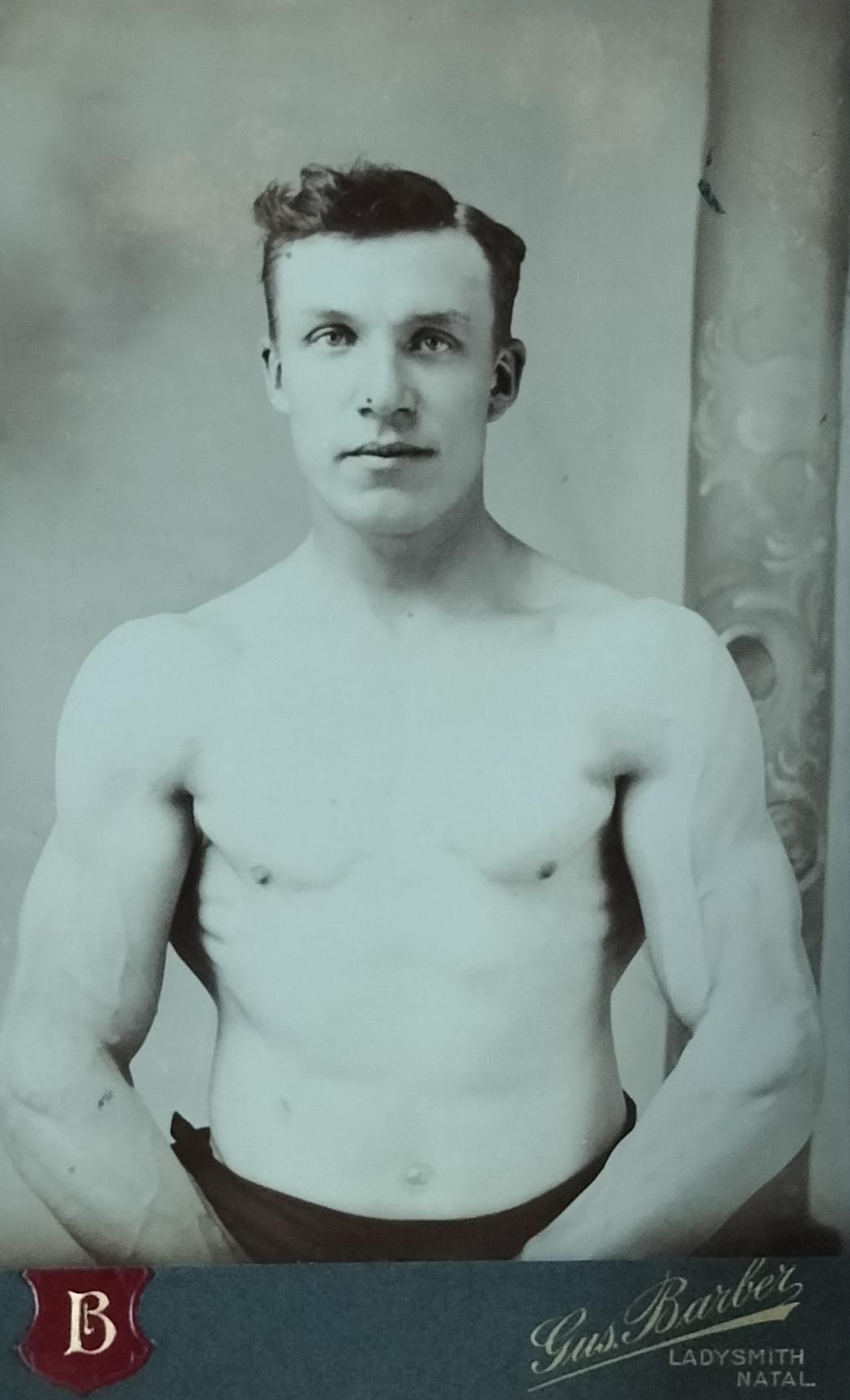

Cabinet Card format photograph by Ladysmith-based Gus Barber of an unknown young bodybuilder (circa 1908). Is it justified to destroy this image because we do not know who the sitter is – an argument used by many who elect to throw away images: “We do not know who these people are”?

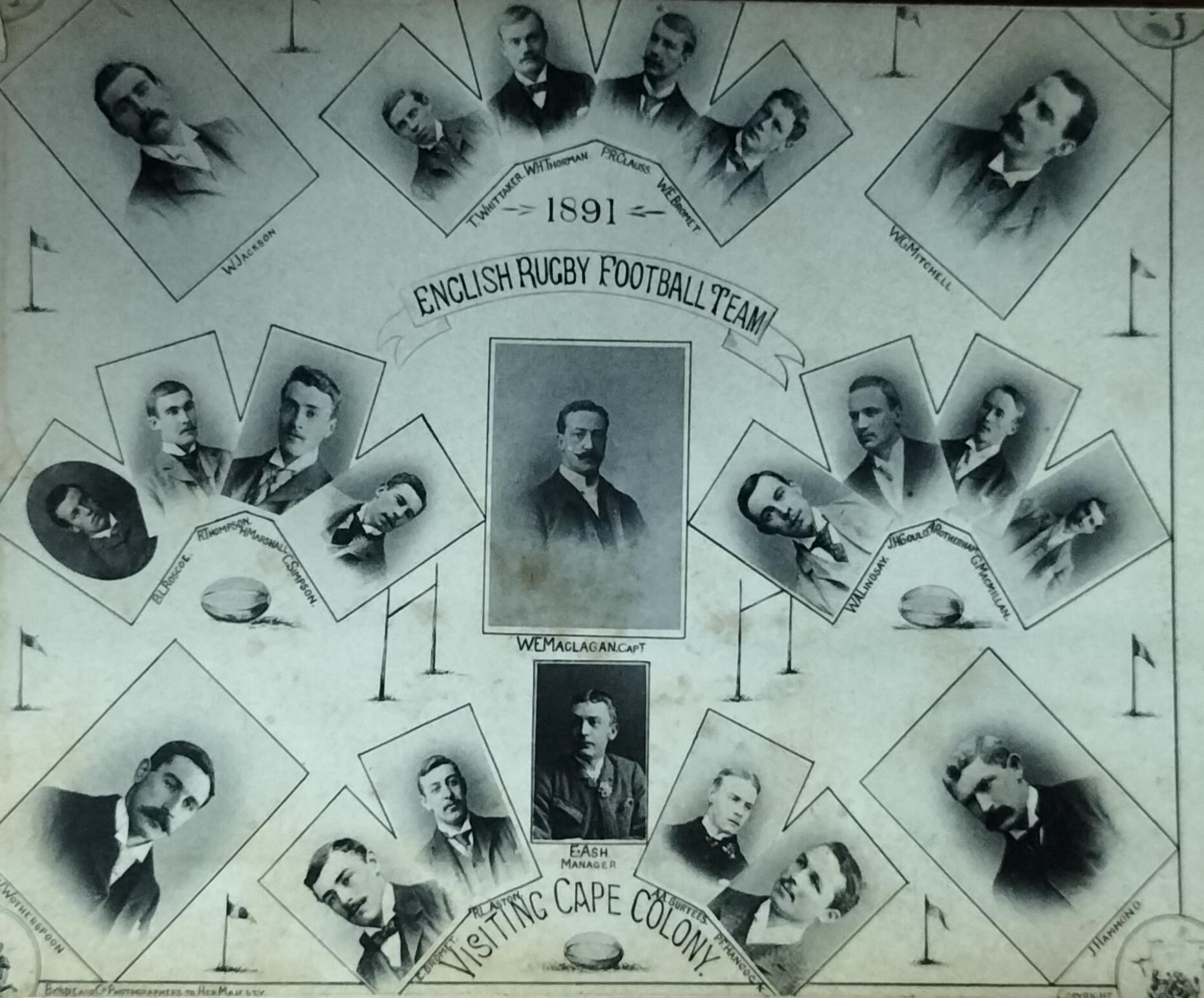

Not entirely a South African photograph, but still relevant in that it contains the details of rugby players who toured the Cape Colony in 1891. The name of each touring player is included in the photograph. Although commercially produced, images of this nature remain of significance to sports historian.

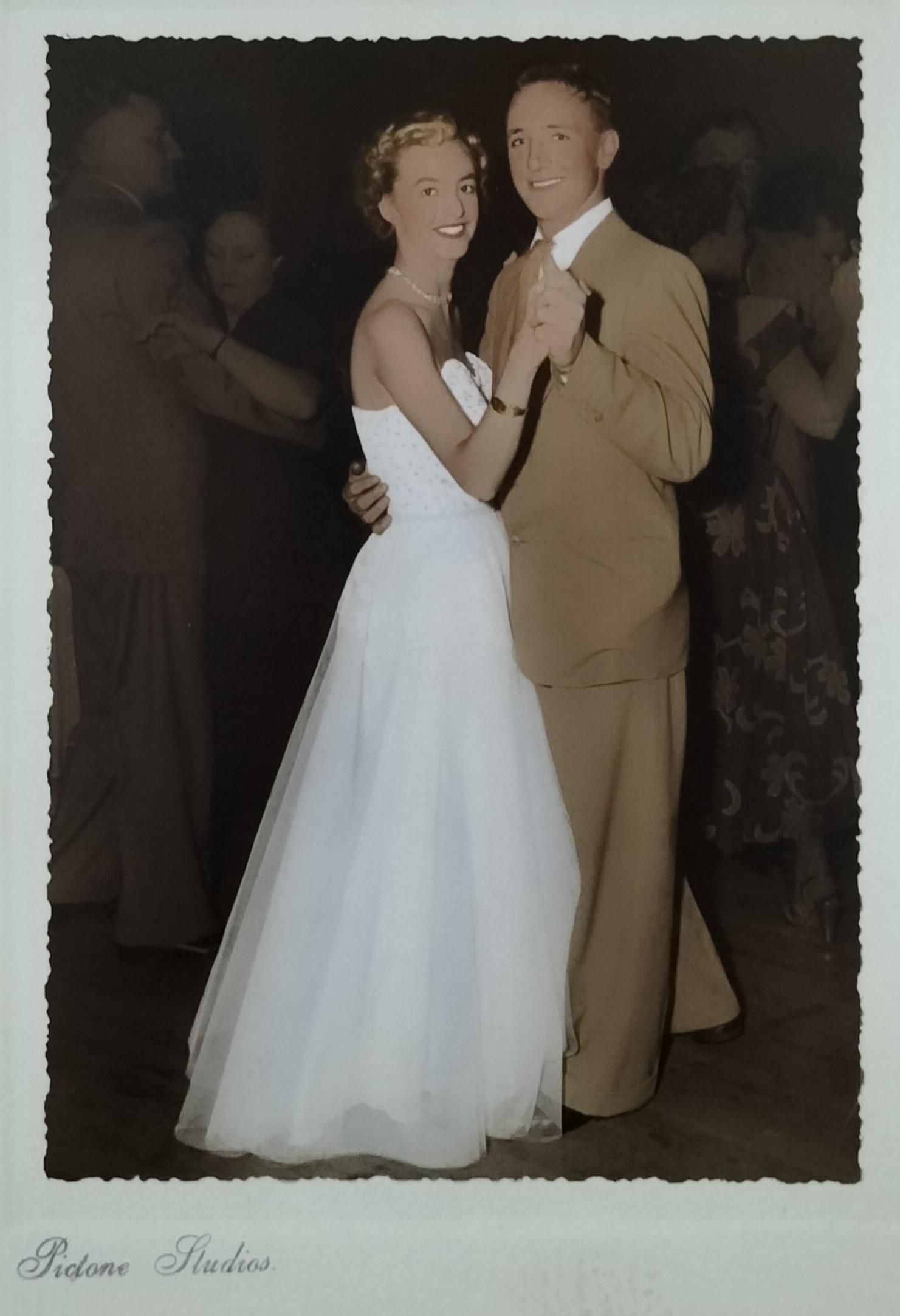

1950’s Hand-coloured photograph of an unknown couple. Photograph by Pictone Studios. What makes this photograph significant is the colouring style applied. Note how the dancing couple is brought to the fore whilst others on the dance floor have been faded. The colouring style is significant to justify the retention of the photograph for heritage purposes.

A large format photograph of the Vlakfontein Shooting Club by photographer WH Charters. The date December 1952 appears on the back of the photograph, but this photo more than likely originates from the late 1910s. Although none of the sitters have been identified in the photograph, the names Klasie de Wet and Abram Coetzee are captured on the back.

Cabinet Card format photograph of unknown mother and son. Simply a beautiful composition. Why even consider destroying a photograph such as this?

Large format photograph of an unknown family by an unknown photographer. The inclusion of the portrait photograph on the lap of the older male sitter (probably of the mother/grandmother of all the sitters) suggests that this is a memorial photograph.

2) Copyright on Photographs

Copyright entails legal ownership of intellectual property, including the photograph. It grants the photographer the exclusive right to control the publication, reproduction, distribution, and other uses of their work. This protection incentivises creativity and provides creators with a means of financial compensation.

In South Africa, the copyright of a photograph generally expires 50 years from the end of the year in which the work was first published. If the photograph was not published within 50 years of its creation, the copyright expires 50 years from the end of the year the work was made. This differs from copyright on literacy, musical, and artistic work where copyright exists for the life of the author plus 50 years following their death.

Unlike other forms of intellectual property, it is not possible to register copyright photographs in South Africa. The person who captured a photograph is generally considered the owner of the copyright of the resultant image. This means that the photographer holds the rights to the image they captured by default. Nuances do, however, apply; for example, if the photographer works for an employer, the copyright may vest with the employer.

Based on the above, at the time of writing, the copyright on photographs captured before 1975 (as of the date of publishing this article) would have expired.

In a recent article on the Pretoria-based photographer, Dotman Pretorius, I inadvertently used photographs captured by him post-1975. This raises two critical questions:

- Where a heritage article is solely about the photographer and he/she is fully acknowledged, could it still be viewed as a copyright infringement?

- Should the law view it as a copyright infringement, how would the copyright on the use of an image be claimed or enforced – considering that the photographer is no longer alive? Pretorius also had no children that could possibly enforce such infringement.

So often online dealers or collectors claim copyright on historical images, but it is not possible to register copyright photographs in South Africa in that the original copyright vested in the photographer (which often has expired). While it is understood that certain images carry significant value and that the owner wants to protect their investment (buying antique photographs can be expensive) by preventing unauthorised use, placing a copyright on the image is not the answer. The more seasoned dealers will place an emblem or item on the photograph when placing the image on the internet to prevent unauthorised use without acknowledging the source. Ironically, modern technology (or AI) can now circumvent this.

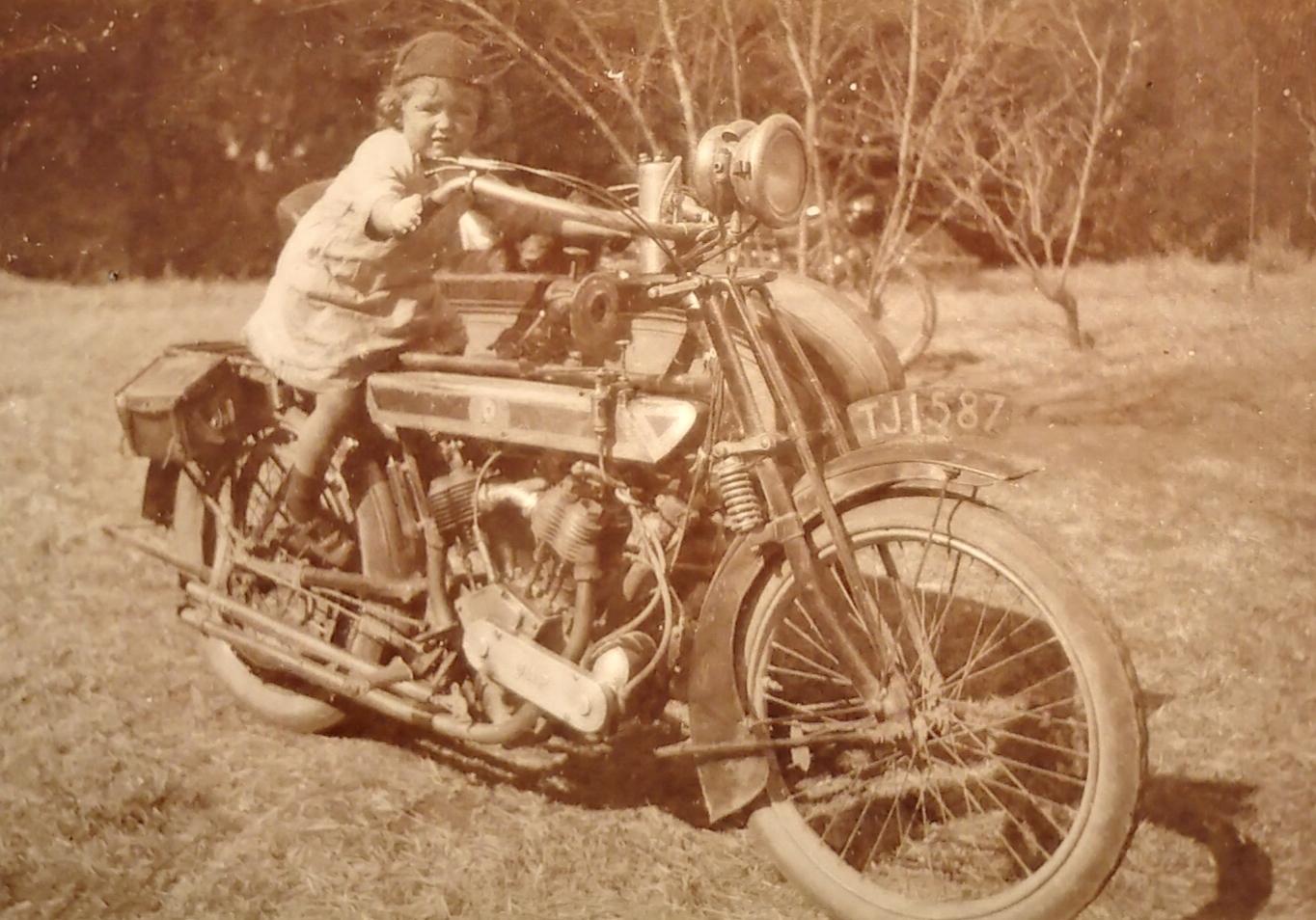

An amateur photograph of an unknown little sitter (circa 1920s) captured in Johannesburg – See the TJ number plate. This photograph was found in a large scratch box (in which photographs were getting damaged) at a car boot sale. The dealer in turn obtained the photograph from a charity store - thank goodness. Future research will determine what type of motorcycle this is.

This black and white photograph (circa 1950) of an unknown telecommunications technician at work is an example of an “occupational” photograph. With the development in technology, this photograph has already become of significance in terms of our heritage.

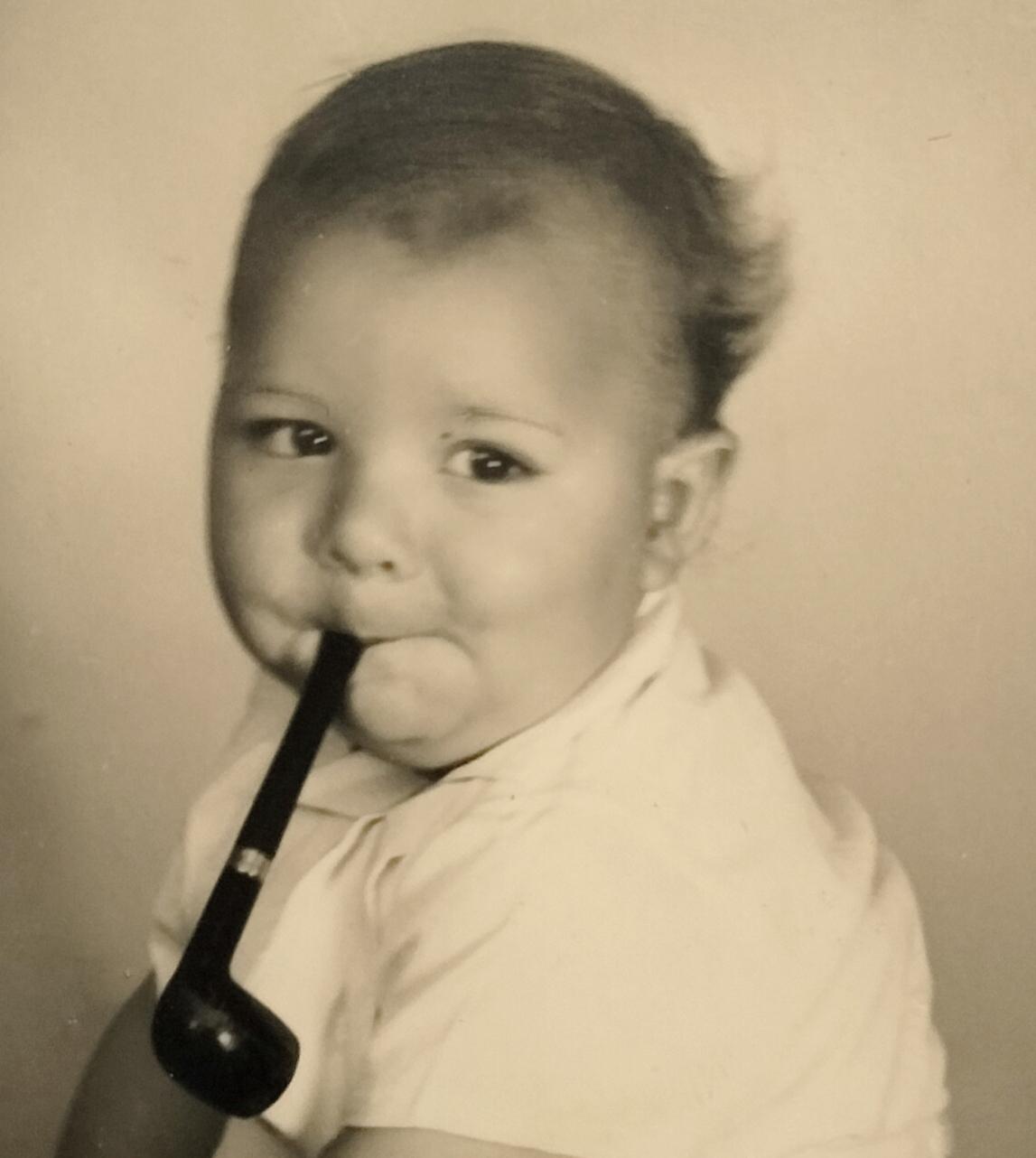

Now this is funny. Why destroy a photograph such as this? Unknown sitter and studio photographer (circa 1960). Even though the little pipe smoker may well still be alive, there are no legal restrictions in placing an image such as this.

A black and white photograph of colleagues on the South African Railways. The photograph of the unknown blue-collar workers proudly standing on a loco that they probably maintained, was captured in Greyville near Durban in 1947.

Black and white holiday snapshot of a Central African Airline aircraft at a local airport (circa 1960). A photograph such as this is potentially seen as “boring” by many, but will be of potential interest to someone somewhere along the line.

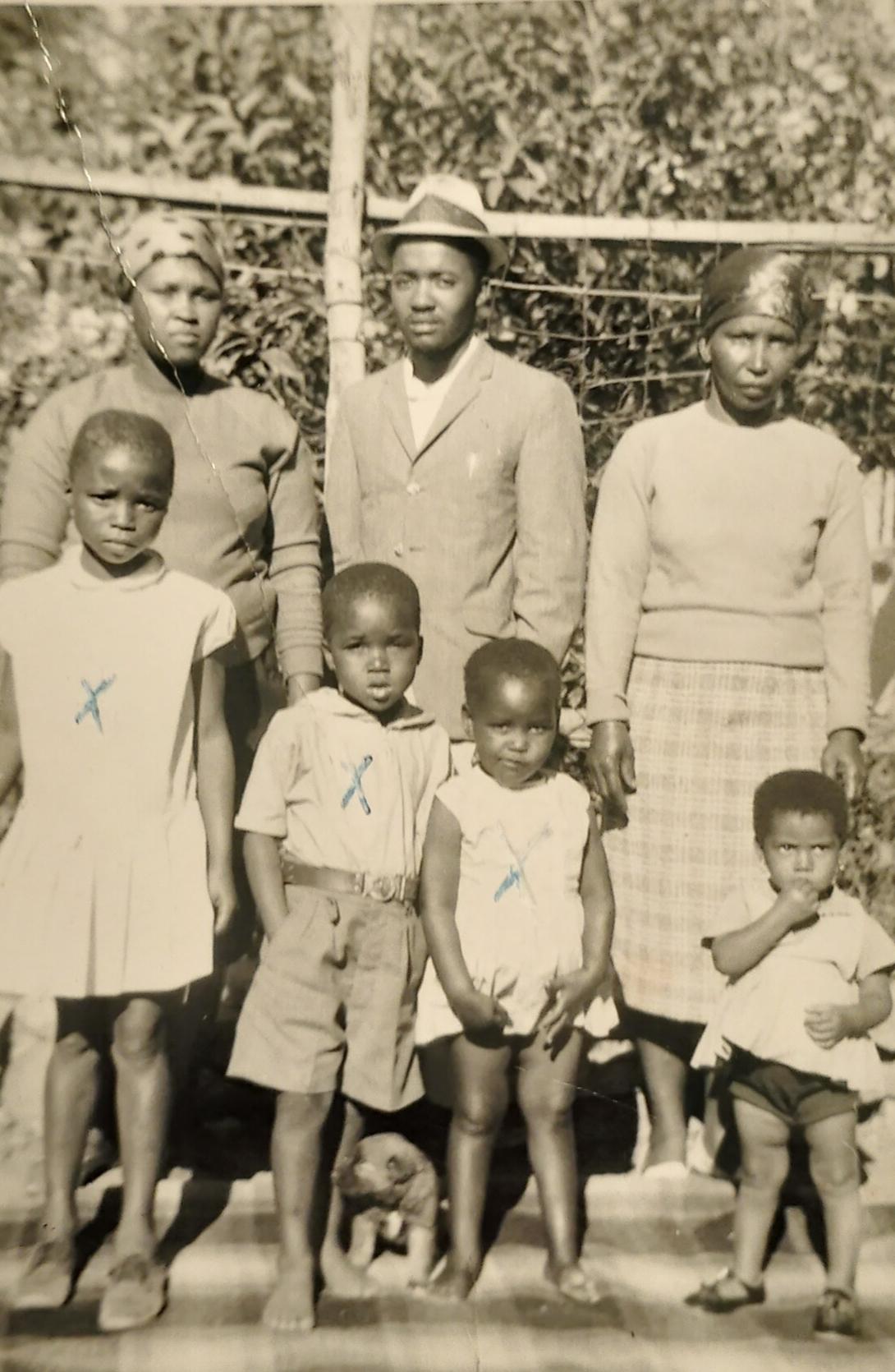

A black and white snapshot photograph of an unknown local Black family (circa late 1950s). Of particular interest for researchers would also be – who was the photographer – a professional or an amateur family photographer? Social family photographs of Black South African residents are not readily found and deserve proper curation.

3) Secondary considerations related to the use of heritage photographs

One charity store assistant once stated: “What if the buyer finds photographs of nudes amongst the donated photographs?”.

I must concur, it may happen, but so what? I once did find a larger format amateur nude photograph in a Cape-Town based shop, captured during the 1920s. It was tastefully done – It is beautiful - It tells a story. Although the person posing in the nude is unknown, should this image be used in the future, the only aspect that may need to be considered is the dignity of the family. Who would want to see a great-great-grandparent in the nude? Buying, owning, or selling such an image is, however, not unlawful.

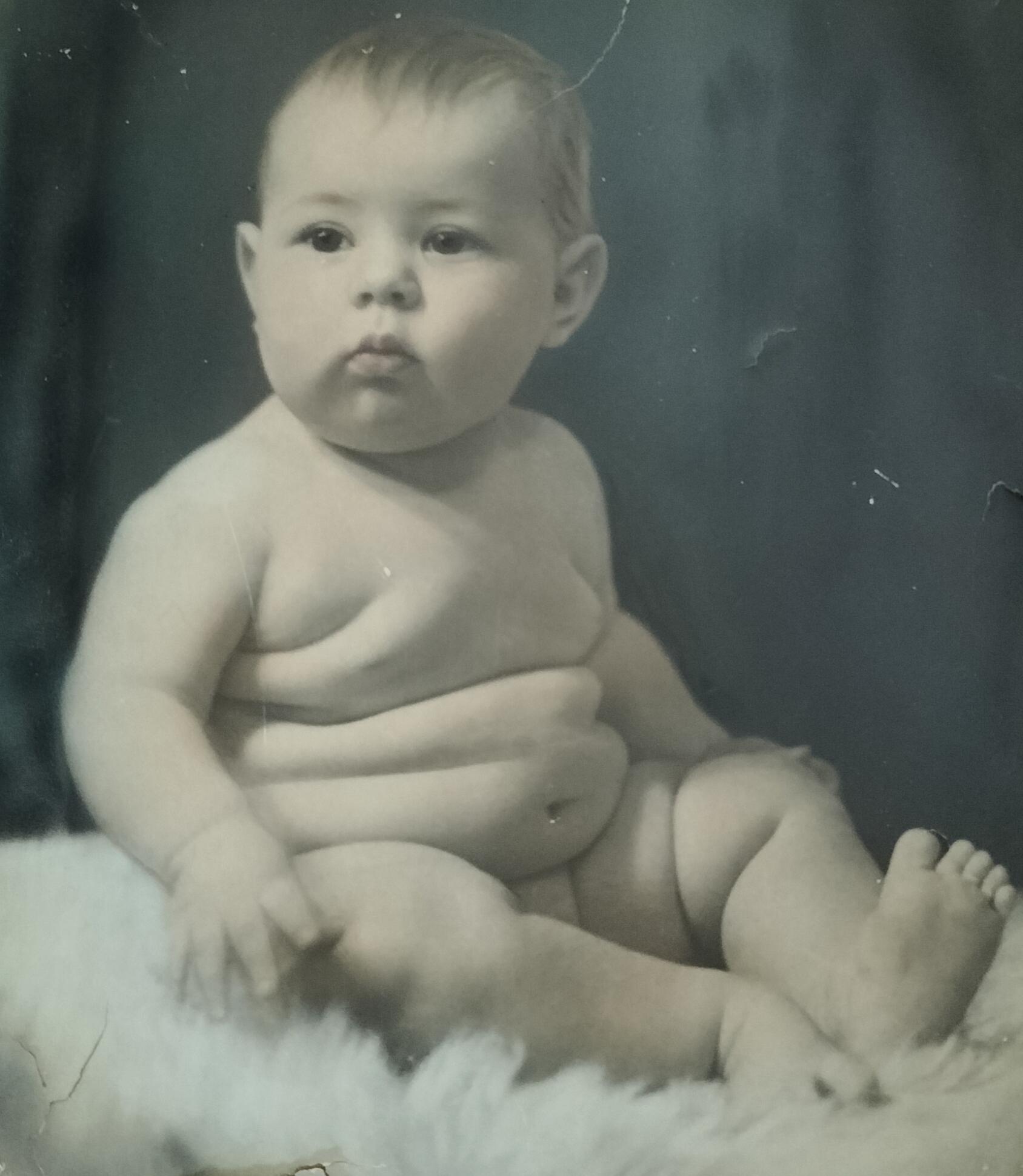

A borderline aspect is when it comes to photographs of babies posing in the nude. Do not be mistaken - It was a popular posing style – these images are aplenty in different photographic formats but are mainly found in cabinet card formats (1880s – 1910s) and picture postcards (1910s -1930s). Parents brought their babies into the studio and had their baby pose in the nude. These images were typically captured of the child lying on a blanket on their stomach. Although photographers (and parents) ensured that no genitalia were captured, these images do border on possible child pornography and may need to be used with caution.

Klein kaalgat. An unknown child posing in their birth suit. This large portrait (circa 1920s) would have been proudly on display in the family home. Photographs of this nature were not uncommon posing styles applied by studio and amateur photographers alike. From a conservative perspective, some may view these images as bordering on child pornography. Publishing an image such as his is, however, not transgressing any South African laws as it relates to a photograph. Would it not be great if the modern family recognised this baby, what today would be their great-grandparent or grandparent?

Another aspect that requires caution (in my mind) is the use of Eurocentric Ethno photographs. These are images captured by foreign photographers of our local population for commercial reasons. The Europeans (and other nations) had an insatiable curiosity about southern Africa’s ethnic diversity. Many of the resultant images are therefore condescending Eurocentric poses or showing the diverse cultural groupings in the nude – including children. Although these photographs portray the rich heritage and realities of that era, they may, today, be viewed as patronising/disdainful.

Closing

In short – There will be no copyright infringements on photographs from before 1975 (at time of writing) nor can there be any POPIA infringement on the use of photographs from before 2013. This substantiates my stance – photographs are being unnecessarily destroyed due to an angst around what some laws are perceived to prescribe.

A family member, two or three generations removed from an original photographer, recently suggested to me that I cannot use the photographs produced by one of their great-grandfathers without their permission. As it is, the relevant photographs currently curated in the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection were initially obtained on the open market. The question is: Did the person have legal standing in their stance? Based on the above, I do not believe so.

To take it a step further, considering that photographs are generally used for research publications or heritage articles, can it be argued that the use of any images, where parties are still alive, conflicts with any of the two laws mentioned above? My personal view is – Unlikely, in that the intent in the use of the photograph, namely photographic historical purposes, should then become the overriding factor.

I’m also not aware of any South African case law in terms of the copyright transgressions as it relates to the use of photographs younger than 50 years.

Recently, I heard a question posed to listeners on a radio station. The question was: What is the first thing you may want to rescue when your place of residence is on fire? The standard response was: My photographs! This confirmed for me that there is still a sentiment in the “old-fashioned” printed imagery, a concept that will fade within the next 30 years or so due to most of our images now being stored on our cellular phones and in the cloud. The challenges of images being digitally stored make for a separate article.

Back to charity organisations. Although donations to charity organisations are a better route than simply tossing them in the bin, potential donors are recommended first to check with the charity institution what they will do with any donated images. If the answer is that they must destroy them, due to the law being prescriptive, consider donating to another charity.

This article has been constructed by a layperson frustrated by the willful destruction of photographs by charity organisations and who is pondering the legal ramifications of the use of photographs for research purposes. No legal opinion was requested as I did not want to incur any cost in my search for an answer.

Any corrections or additional comments by legal practitioners or fellow philaphotographologists (those obsessed with old photographs) would be welcomed.

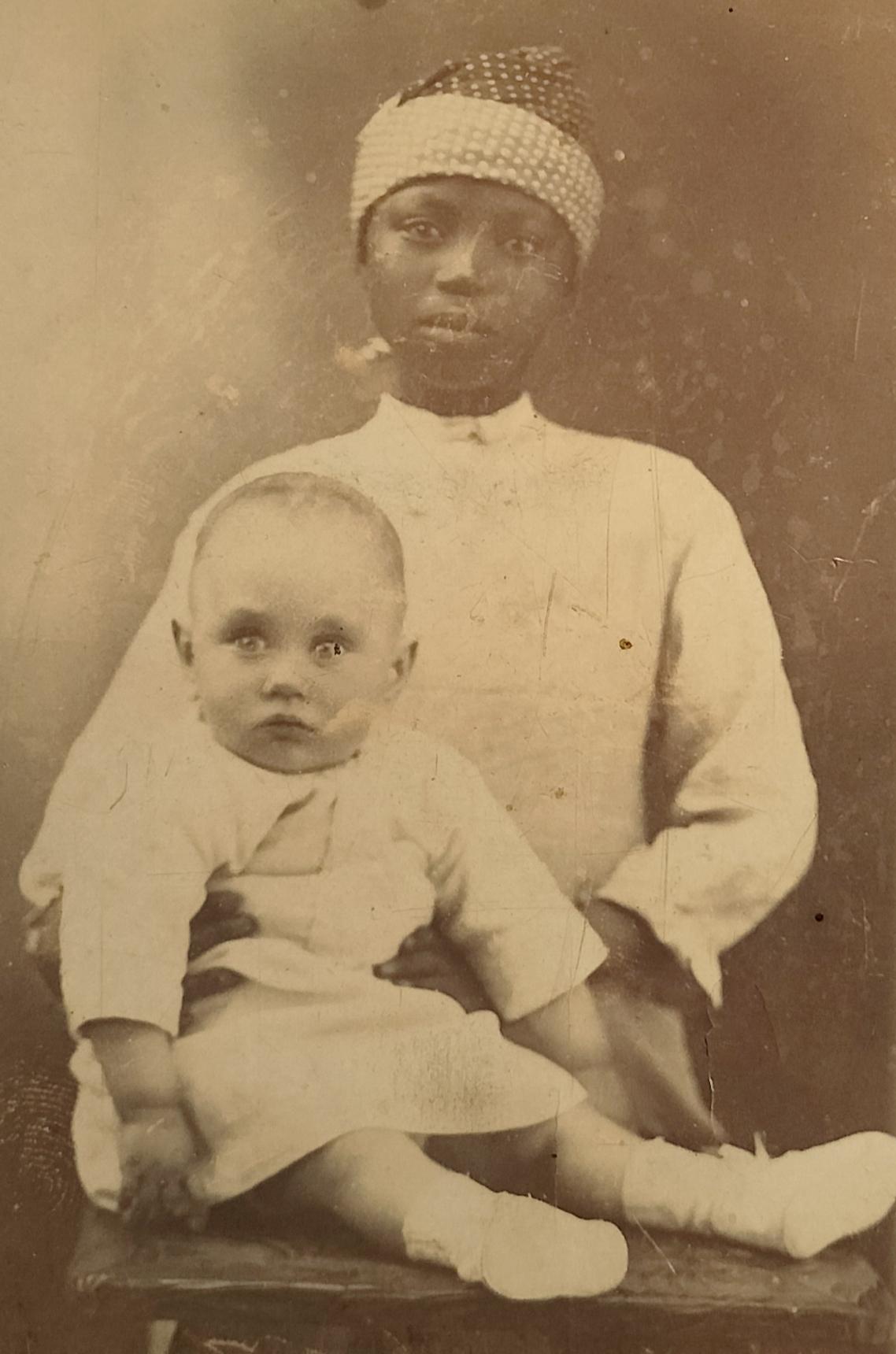

Young William with Daisy by an unknown photographer - 1917. In a South African context, photographs such as these provide insight into our sociopolitical history. Of significance in this photograph is that Daisy is clearly underaged.

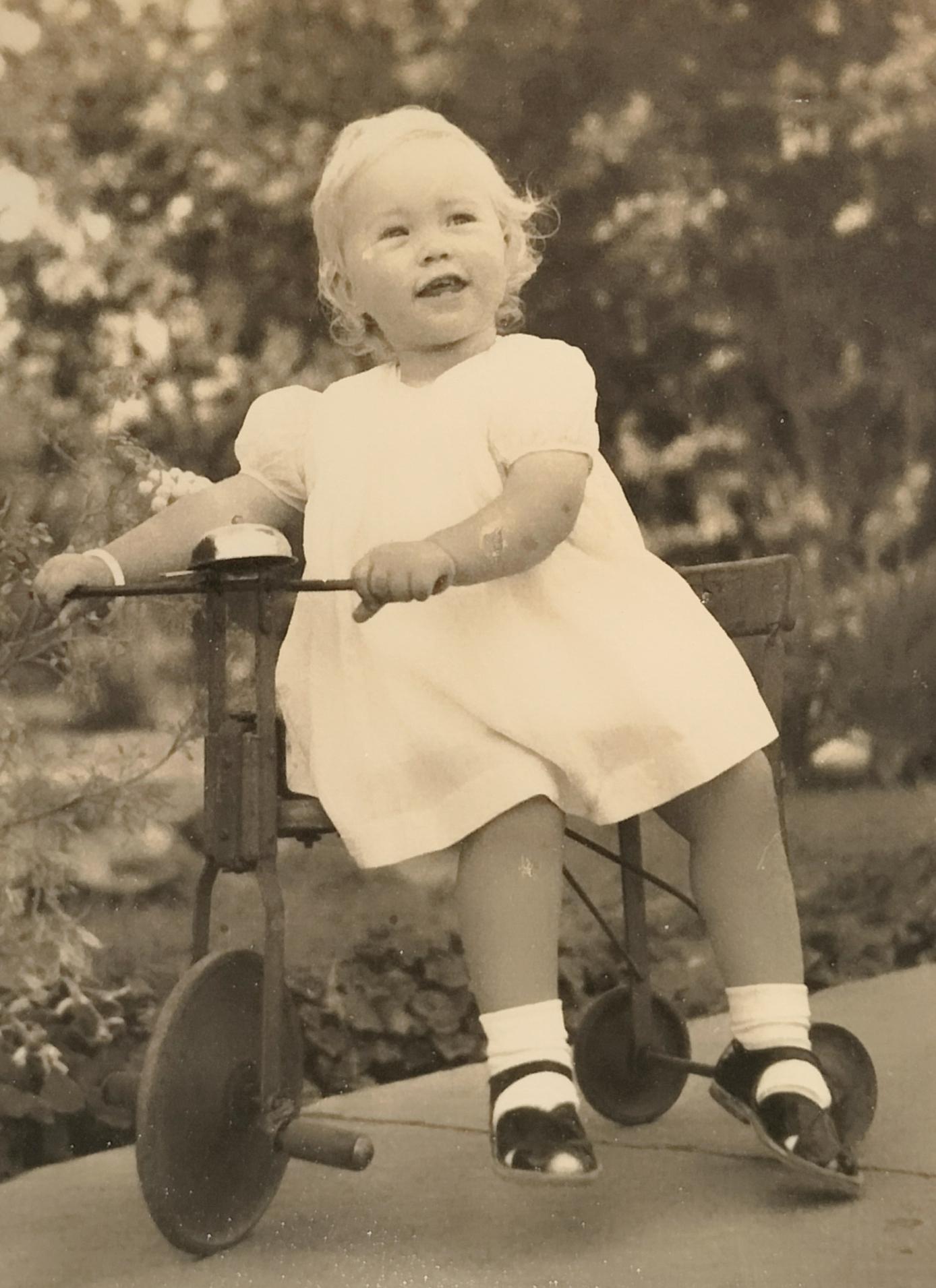

Little sitter that exudes happiness. A photograph of an unknown little girl (circa 1940s). Of particular interest in this photograph is the unusual tricycle she is sitting on, the make of which still needs to be determined.

A privileged little boy in his huge pedal car (circa 1940). Pedal cars have become hugely collectable, therefore the significance of this photograph.

Horsing around – guys having fun, showing off to the camera. Humorous photographs tell us a lot about how people had fun – and what they thought funny at the time.

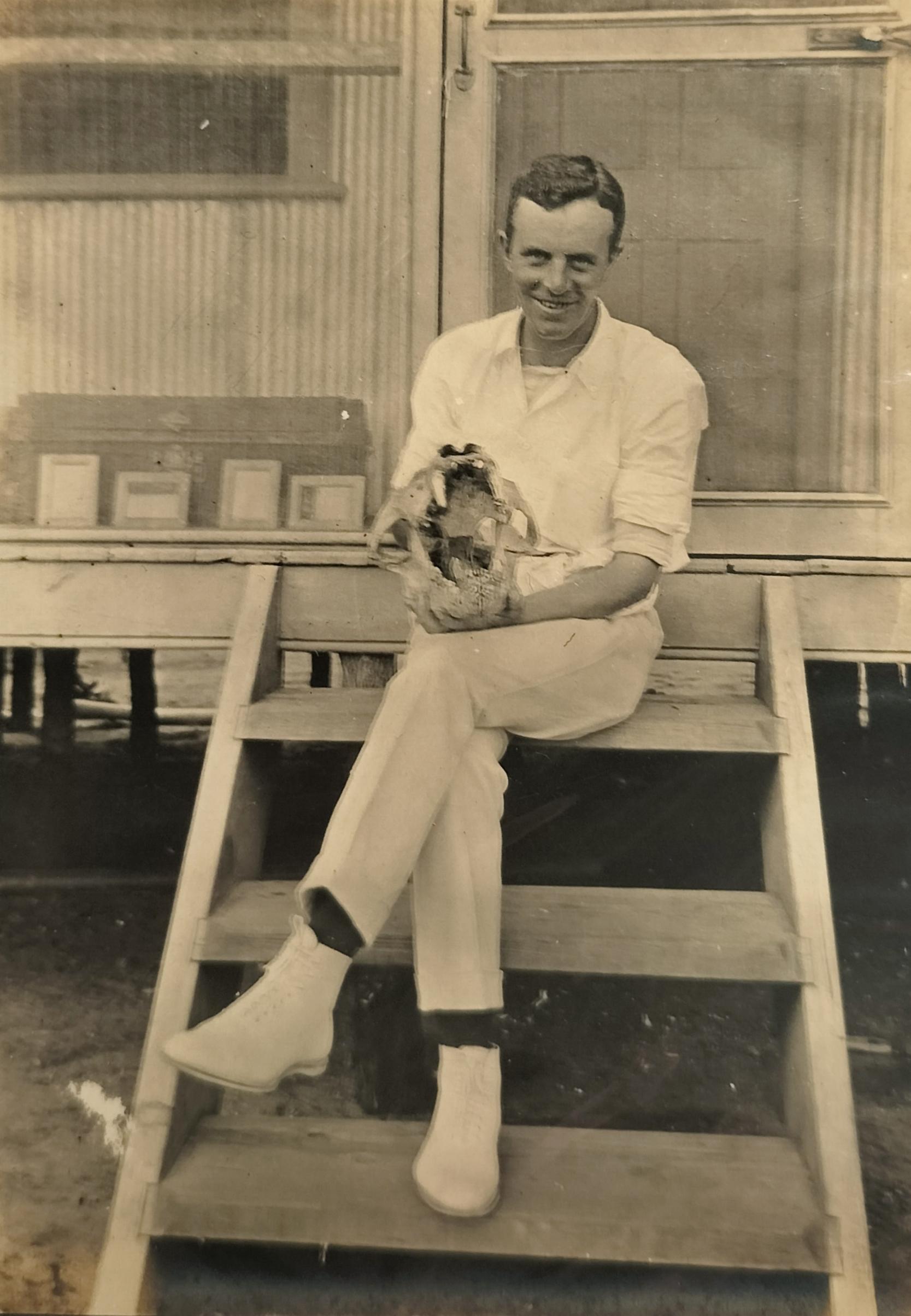

Significance here? Is the unknown sitter holding the lion skull the hunter (circa 1940s)? Although the photograph has little provenance, the lion skull alone makes curating the photograph important as a hunting-themed photograph.

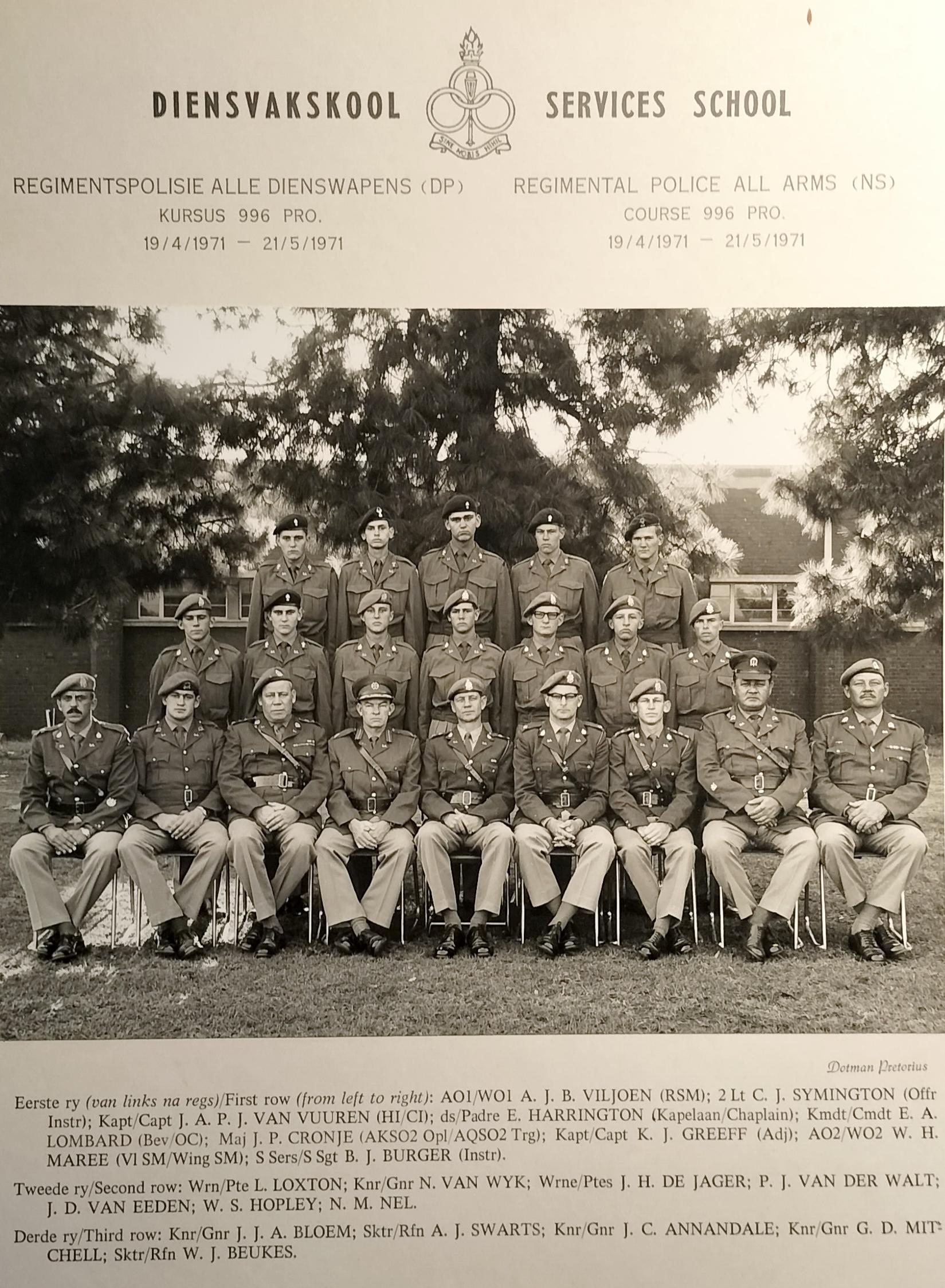

A large format military photograph by Pretoria-based photographer Dotman Pretorius (1971). Images of this nature (military, university, courses, occupational etc.) today occasionally surface at charity organisation that do not elect to destroy photographs. Containing rich genealogical information, they were initially ignored by researchers in that they were viewed as fairly modern. This photograph no longer contains any copyright in that it was captured more than 50 years ago. Some of the sitters, many now in their early to mid-70s, may well still be alive – by placing this photograph, the POPI Act is not transgressed in that the law was only promulgated in 2013.

Main image: World War 2 related black and white snapshot photograph showing “Indian Boys” at the Clairwood camp – Durban (1941). What makes this photograph significant is that the young men seem to be selling fruit at the camp. The destruction of images such as these needs to be prevented in that early photographs of South Africa’s Indian community are uncommon.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- McGregor, S. (2014). Photography Laws for Photographers and people being photographed. Stevenmcgregor.co.za

- Mphahlele, M. (2023). Flashing Lights and Legal Rights: Who owns the Photograph – you or the Photographer (MJMAttorneys.co.za)

- Michalsons (extracted October 2024). Privacy Preference Center. Post-mortem privacy – is it time to prolong privacy after death? (www.Michalsons.com blog)

- Unknown (extracted October 2024). Ask Lawyers: South Africa (Law.justanswer.com)

- Smit & van Wyk (extracted April 2025). Copyright photographs. (www.svw.co.za/copyright-photographs)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.