Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The South African Border War had an immense social, cultural and political impact on South African society at the time. It resulted in unnecessary loss of life and much trauma, not only for the conscripted men, but also families back home.

The South African Border War, also referred to as the Namibian War of Independence or the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict (a war between a standing, professional army and an insurgency or resistance movement) that occurred in Namibia (the then South West Africa), Zambia, and Angola between 26 August 1966 and 21 March 1990. It was fought between the South African Defence Force (SADF) and the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), an armed wing of the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO). The South African Border War resulted in some of the largest battles on the African continent since World War II and was closely intertwined with the Angolan Civil War (information sourced from Wikipedia).

On 4 August 1967, military service became compulsory for all white men in South Africa over the age of 16 (conscription). Deferment to complete schooling or a university degree was granted, but very few of them were exempted from conscription. The end of military conscription was announced during 1993.

Although most young men did not have an understanding as to why they were conscripted into the South African military in the first place, followed by unanticipated indoctrinations, this article will avoid expanding or reflecting on the political ideologies around military conscription in South Africa at the time.

An unknown corporal aiming his R1 rifle – This was probably an image reproduced in order to be sold to servicemen during 1979

This article is ultimately about photography during the above-mentioned period – about forbidden photography.

Images presented in this article were all taken by national servicemen who would have illegally smuggled their elementary cameras (mostly Kodak Instamatics) into the various training bases or to the border. National servicemen were creative in hiding their cheap mik-‘n-druk (aim and press) cameras.

Whilst it was illegal to take photographs, there were inevitably those conscripts who ignored the rules, aiming their cheap, instamatic cameras at whatever they could, but usually among comrades or when it was considered safe to do so.

For those conscripted into the military at the time, the law around the prohibition of being in possession of a camera or the taking of photographs was clear in that section 119 of the South African Defence Act (Act No 44 as amended) stated:

1) No person shall, unless authorized thereto by the Minister of Defense or on his authority, -

- take any photograph or make any sketch, plan, model or note of any area defined by the Minister by notice published in the Gazette or in any other manner which he considers sufficient in the circumstances, or of any part of any such area or any object therein; or;

- have in his possession in any area so defined any camera or other apparatus which may be used for taking of photographs.

The stipulated law then continued stating that any camera or any film may be seized by any member of the South African Defence Force and may after investigation by, and on authority of the Secretary for Defence, be declared by him to be confiscated by the State.

The above was summarised in manuals used during basic training under the heading “Photography” (Blake 2011):

- Any unauthorized use of cameras and other photographic equipment is forbidden. This particular equipment can be confiscated by any member of the SADF;

- Before any photo of any installation within a military area is taken, permission must be given by the security officer;

- Any member in possession of a camera, who does not declare it, is guilty of an offence;

- Permits must be issued by the security officer for those in possession

Military training at the Heidelberg military base during 1979. This image was taken by a corporal and sold to the men undergoing training.

Group of national servicemen undergoing training - in front of the military barracks at Heidelberg (early 1979). Exhausted recruits after a day out training. An image that would have been sold to the group by a instructors.

Considering the above, any photograph therefore taken without approval became a “forbidden image”. The consequences for any national serviceman would have been severe if caught being in possession of either a camera or any image captured during training or whilst on the border.

The purpose of this article is therefore to reflect on photography during military conscription and include some images that were “illegally” captured by the young men – be that during their 1 or 2-year conscription period, or be that whilst they had to attend compulsory annual military border camps (ranging from one to three months).

Both Blake (2011) and Steenkamp (2016) have amassed an incredible number of images for their respective acclaimed publications on the border war.

The Blake (2011) publication mainly includes images taken by the servicemen at the time, whilst the Steenkamp (2016) publication mainly includes images taken by the then war correspondent Al Venter as well as images obtained from other sources such as the South African National Defence Force Document Centre or the National Museum of Military History.

Most of the images in the Steenkamp (2016) publication were therefore taken by officially appointed and “licensed” photographers or photojournalists. The images contained in his publication are therefore generally of a better quality compared to the images included in the Blake publication or those included in this article.

It is unlikely that any conscripts would have had cameras with them whilst undergoing their 3-month basic training. Images that exist of conscripts undergoing training in various military bases in South Africa would have been taken illegally by officers or non-commissioned officers (many of them conscripts themselves), who would then sell these to the younger conscripts undergoing training.

Two corporals in their PT gear – Heidelberg - 1979

Chasing the platoon of recruits through a muddy pond. This exercise was repeated three times on the particular day. Each time with a new set of clothing. The next day all three sets of clothing had to be washed, dried and ironed. This was an image sold to troops by the instructors.

On the shooting range. Location unknown.

Whilst Instamatic cameras were small and easy to smuggle into military bases, the quality of the images were not nearly the same compared to those that would have been produced by the more effective single lens reflex cameras of the time – Such cameras would have been more bulky and difficult to hide.

Even though photographic technology had improved over the years, the border war snapshot images produced by the servicemen (also commonly referred to as “troepies”), were generally also of lower quality compared to the images taken by soldiers during the Anglo-Boer war at the turn of the previous century.

This results in border war images not being that attractive because they were taken by amateurs with cheap cameras. The development of the images at the time was also not of the best quality, resulting in the deterioration in colour over time.

Many images are therefore poor in quality, often blurred and off-centre. Most of the amateur photographers also did not have a natural ability in terms of photographic composition. The photographs can therefore be described as mundane and amateurish at best.

But why would soldiers have wanted to risk being caught by illegally capturing images? It was about visual evidence that soldiers could bring home. It would also have contained an element of sense-making of their experience away from home. Why am I here? What is this all about?

Existing images furnish photographic evidence of conscript life in the South African Defence Force. The pictures may be distorted but they do reveal the actual lived experiences of conscripts at the time. Photographs captured by servicemen mainly focussed on life whilst in camp. There is limited aggression involved in border photography. Although gruesome images were also captured, these were in the minority. Amateur images of actual battle would be few and far between.

The narrative presented around the experience of the war, both visual and verbal, would have been very different for the conscripted national serviceman compared to high-ranking officers or professional soldiers.

Images taken during the border war period have become of significant interest and value. They provide insight into our recent military history. Unlike images from the Zulu or Anglo-Boer wars, where the modern-day viewer has no first-hand memory of the conflicts, the border war images, when combined, do provide a collective memory to those who lived the experience.

Border war photographs would fill in the blanks in most servicemen’s mental picture of the past. Some sentimentalism would be included in images taken during military training or on the Namibian border. It is all about a brotherhood, and although the images were produced by a small percentage of the population, it remains a combined sentiment by and large.

Let’s see how this Unimog performs in the sand. Troops fooling around in a military vehicle on the river banks of the Zambezi during 1980. The fact that they are seen in civilian clothing confirms that they were probably off-duty for the day.

Doherty (2014) argues that photographs are themselves complex and constructed objects that do not provide a simple truth about either history or memory, whilst Sontag (1977) adds that a photograph cannot be an independent source of meaning.

Considering the above, single images or small, private border war image collections can only provide a single memory (to the owner of the images), a memory that may be a restricted and narrow memory by and large. Combining the narratives and images of the men who were on the border may however contribute to a better collective and shared memory. By combining images, as done by Blake (2011) and Steenkamp (2016), it assists in the lived experience being etched into the collective memory.

Sadly, many of these forbidden images have already been discarded. They typically ended up in the old-fashioned photograph albums of the time where the album had a sticky surface over which a cellophane type cover was placed. In many instances, these photographs could not be removed from the albums without damaging them – due to them being glued to the page.

Border war images are no longer commonly available for various reasons:

- Not many servicemen would have wanted to risk being caught with an “illegal” camera;

- The images still form part of many older servicemen’s private photographic collection of their personal life journey;

- They have been thrown away or destroyed.

During the years of the war, the South African government and military attempted to keep the full extent of the war from the South African public. Censorship existed to keep visual reality away from the South African public. Through a variety of mechanisms, including outright censorship and management of the news process, the South African public was kept ignorant of the scale and intensity of the warfare on the Namibian border (Doherty, 2014).

As suggested by Doherty (2014), the existence of the forbidden images indicates ill-discipline within the SADF at the time. This aspect is further confirmed by some of the images included in this article.

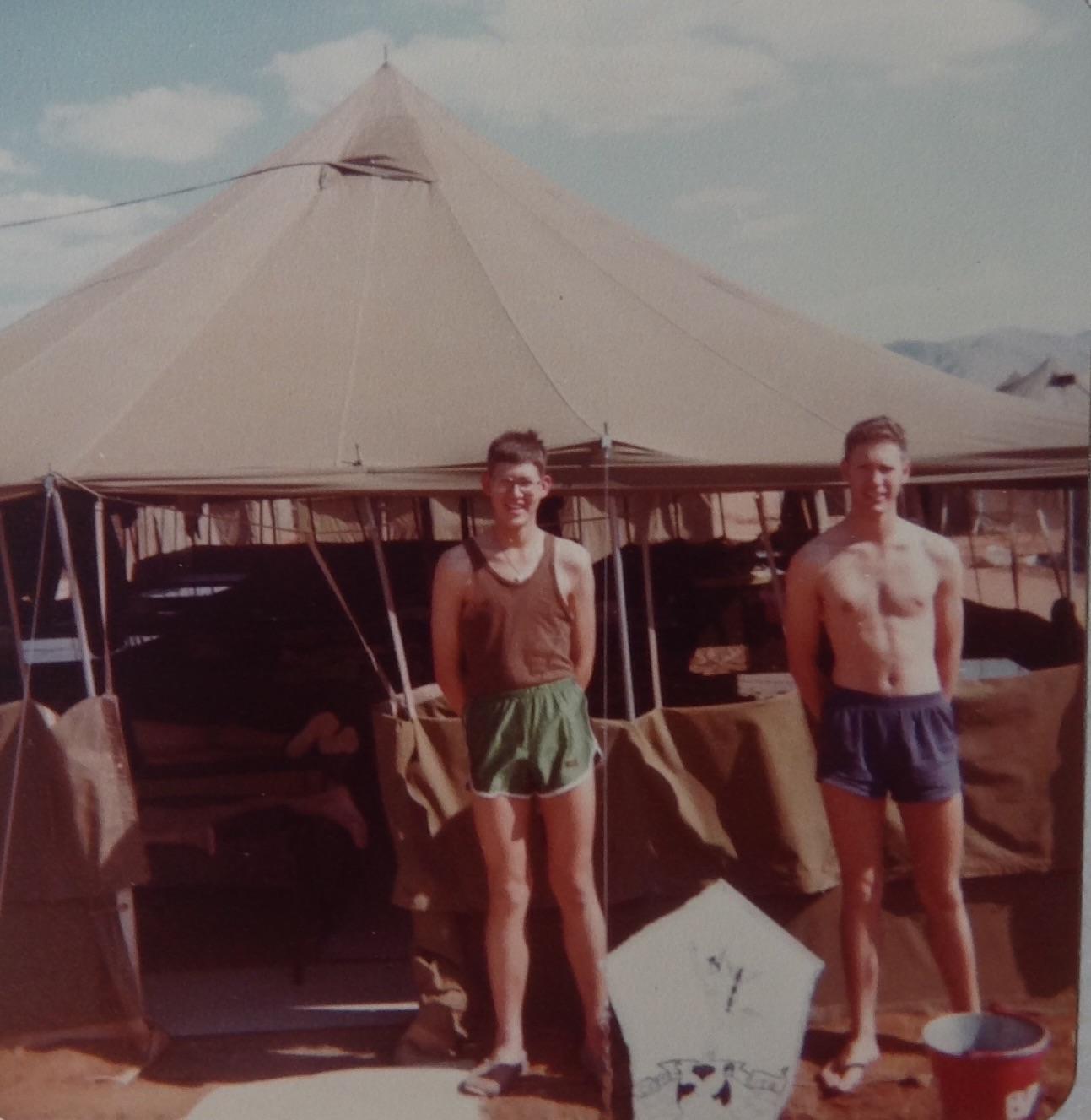

Windhoek - 1979. The homemade sign (on white board) shows the signaler emblem suggesting that these chaps are signalers. Other men can be seen lying on their beds in the tent

Windhoek – 1979. Group of signalers posing for the camera

Blake (2011) quoted the following response by a national serviceman he interviewed:

I took many photos while on the border and in Angola. You weren’t supposed to take photos, but you didn’t really give a damn. You just did it. Took a few with my little Instamatic, nogal (of all cameras). If you were bust with a camera you’d get in a lot of trouble. You weren’t supposed to have them – but that was my challenge.

Given the above narrative, the author, a national serviceman himself, never became aware of a serviceman being court martialled because of him having an “unlawful” camera in his possession.

Blake (2011) also quoted a national serviceman’s account of handing in his film spools at a chemist for development. The serviceman mentioned that he would only receive back the mundane images post development and not the images of “enemy” corpses that he had taken. This narrative begs the question as to whether he then would have received his negatives back at all or whether his negatives would have been cut to exclude these alleged images of “enemy” corpses. Although possible, the author argues that this version is more than likely improbable in that this type of censorship would not have extended beyond the borders.

An ex-lieutenant, in service during the latter part of the conscription campaign, confirmed that when young men reported for their first day of duty in the military, that officers would inspect the young men’s personal belongings and confiscate any cameras – and there were many, he added. This confirms that there were attempts to eradicate cameras from the military, but that these efforts were not sustainable, more so during the latter years of the campaign.

The real question is: How many servicemen would have had cameras with them whilst on the border? It has been suggested that some 600 000 men were conscripted. It is not clear how many of these men ended up on the Namibian border. It would have been the larger percentage in that this was the ultimate reason for the conscription campaign.

If it is assumed that only 5% of the men were brave enough to ignore the law around photography, it may be argued that around 30 000 illegal cameras may have been on the border. If extrapolated further: - If each serviceman, on average, used two film spools whilst on the border (an Instamatic spool consisted of 24 or 36 images), it would suggest that there must be around 2 million “forbidden” images in circulation – and this is a conservative estimation!

Katima Mulilo – The “lavatree” – A baobab tree with a functional toilet which was often photographed. Also appears in the Steenkamp and Blake publications.

Although relatively contemporary photographic history, surviving border war images remain a crucial part of our country’s history. The effort to collate as many of these images needs to continue in that it will not only assist in strengthening the collective memory for many of the soldiers, but also add to the broader narrative around this period. Surviving images also now have an increased post conscription significance.

The author recently engaged with a philatelist whose primary collecting interest is border war related postal history (cancellations and censor markings on letters). He confirmed that this interest is not to the exclusion of any photographic images taken by servicemen during this era.

Photographic images of the older South African wars, also of much better qualify compared to the forbidden border war images, have generally survived better. Images of the older wars are highly collectable. The author suggests that, although to a lesser extent, images taken during the military campaign in Namibia will also become more collectable over time.

It is the author’s view that although the forbidden images are of poorer quality, they also now need to be curated.

The author underwent military training as a conscript between 1979 & 1980. He completed his basic training at Heidelberg, whereafter he spent some 2 months as one of the first conscripts to be trained as a cryptographer at Voortrekkerhoogte, a role previously only earmarked for permanent members of the Defence Force. After completion of the cryptography course, he spent the remainder of his 18-month conscription on the border – mainly at Katima Mulilo (North Eastern Namibian border).

Soldier resting in a tent with his two little adopted puppies in Windhoek (1979). This means that the soldier must have been settled for a while to be able to adopt the two little puppies.

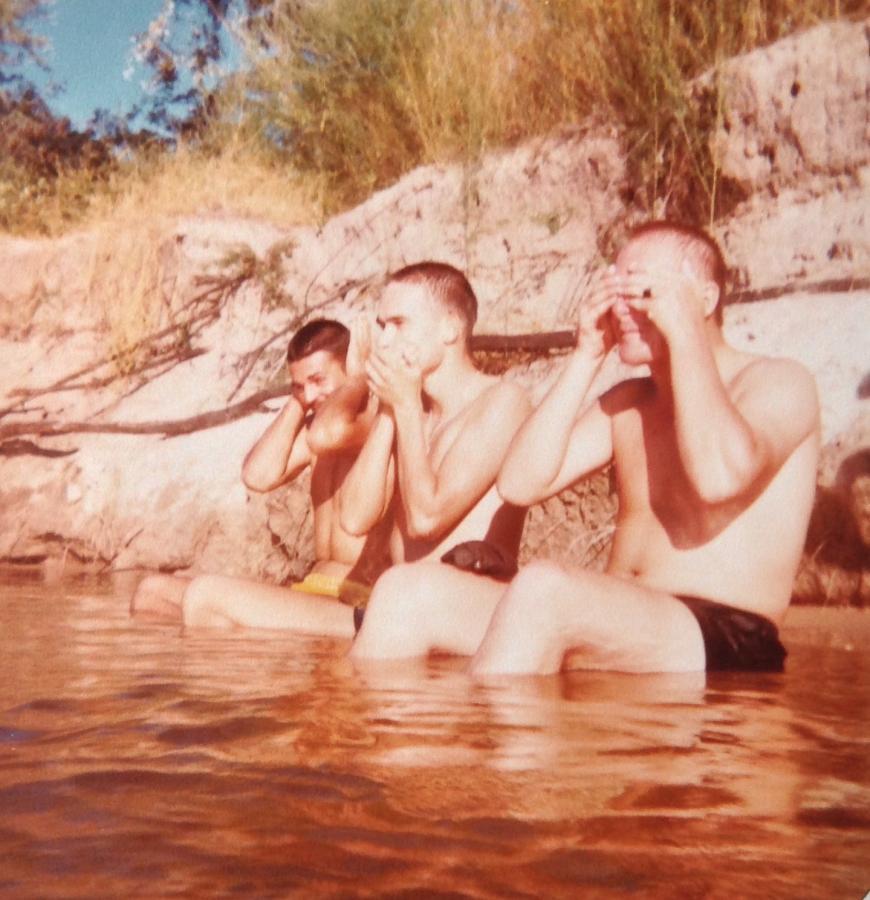

Main image: “I do not see you taking the photo, I may not talk about you taking the photo, I have not heard about the law against photography” – National servicemen on the Zambezi River (near Katima Mulilo) - 1980. The scary part about this image is that the photographer stood in the water and did not even consider the possibility of crocodiles being around.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Blake, C. (2011). Troepie Snapshots - A Pictorial Recollection of the South African Border War. 30° South Publishers. Johannesburg

- Doherty, C.M.W. (2014). Bosbefok: Constructed Images and the Memory of the South African ‘Border War’. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

- Military Conscription in South Africa (www.sahistory.org.za)

- Sontag, S (1977). On Photography. Penguin Books. England

- Steenkamp, W. (2016). South Africa’s border war (1966 – 1989). Tafelberg. Cape Town

- Wikipedia.org (South African Border war)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.