Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We are very excited to publish this detailed article on the life and achievements of Sir William Hoy. The piece was compiled by Dr Robin Lee of the Hermanus Historical Society (click here to view details of the important work carried out by the society). Main image - Hoy's home in Parktown (Wanooka).

“He stopped the railway coming to Hermanus…” - almost every resident of the town knows this much about Sir William Hoy, and many visitors know it too. Perhaps slightly fewer know that he and his wife are buried on the crown of Hoy’s Koppie, because it was his favourite place to sit in the late afternoon, to survey Walker Bay and plan the next day’s fishing with his ghillie, Danie Woensdreght.

Hoys Koppie (Hermanus History Society)

But William Hoy had a life outside Hermanus that renders his actions about the railway to Hermanus an insignificant part of his life’s story. From his base in the Cape Railways and, later, South African Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) he was drawn into some of the major events of the first 30 years of the 20th century.

In this research report I will first give an overview of his career and then explain his involvement in the following historical developments:

- Organising and often personally undertaking repair of railway lines destroyed by the Boers in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902);

- Acting as a key figure in the integration of the four railway systems after the war: the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange Free State, the last two being regarded as one entity and known as the Central Railways (1904-1910);

- Planning, managing and in some cases actually building the equipment needed to transport South African soldiers and materiel into German South West Africa (as Namibia was then) when South Africa invaded that territory at the request of the Allies in World War I (1914-1915);

- Conceiving and carrying out the first electrification of a railway in South Africa, which involved participating in the construction of the first electricity generating plant at Congella, near Durban;

- Accompanying Prime Minister Louis Botha and General Jan Smuts to the Versailles Peace Talks at the end of World War I (1919) and to each Imperial Conference until 1926, when South Africa achieved Dominion status;

- Having responsibility for integrating the railways, harbours and airways into a single state-owned enterprise (1920-1927);

- Playing a key role in promoting the Kruger National Park as a tourist destination by providing rail links to the Park (1923- 1925) and having the SAR publicise the Park at every station;

- Negotiating an agreement with the Wanderers Club in Johannesburg for the purchase of their land by the Railways for the construction of Park Station; and

- Commissioning the panels by Pierneef for the walls of the Johannesburg Station (1927).

The above represent only a part of his activities and, yet, to my knowledge, there is no authorised biography of Hoy. This article may be regarded as a first step in that direction. Thus I have organised the various activities in the chronological order in which they were started.

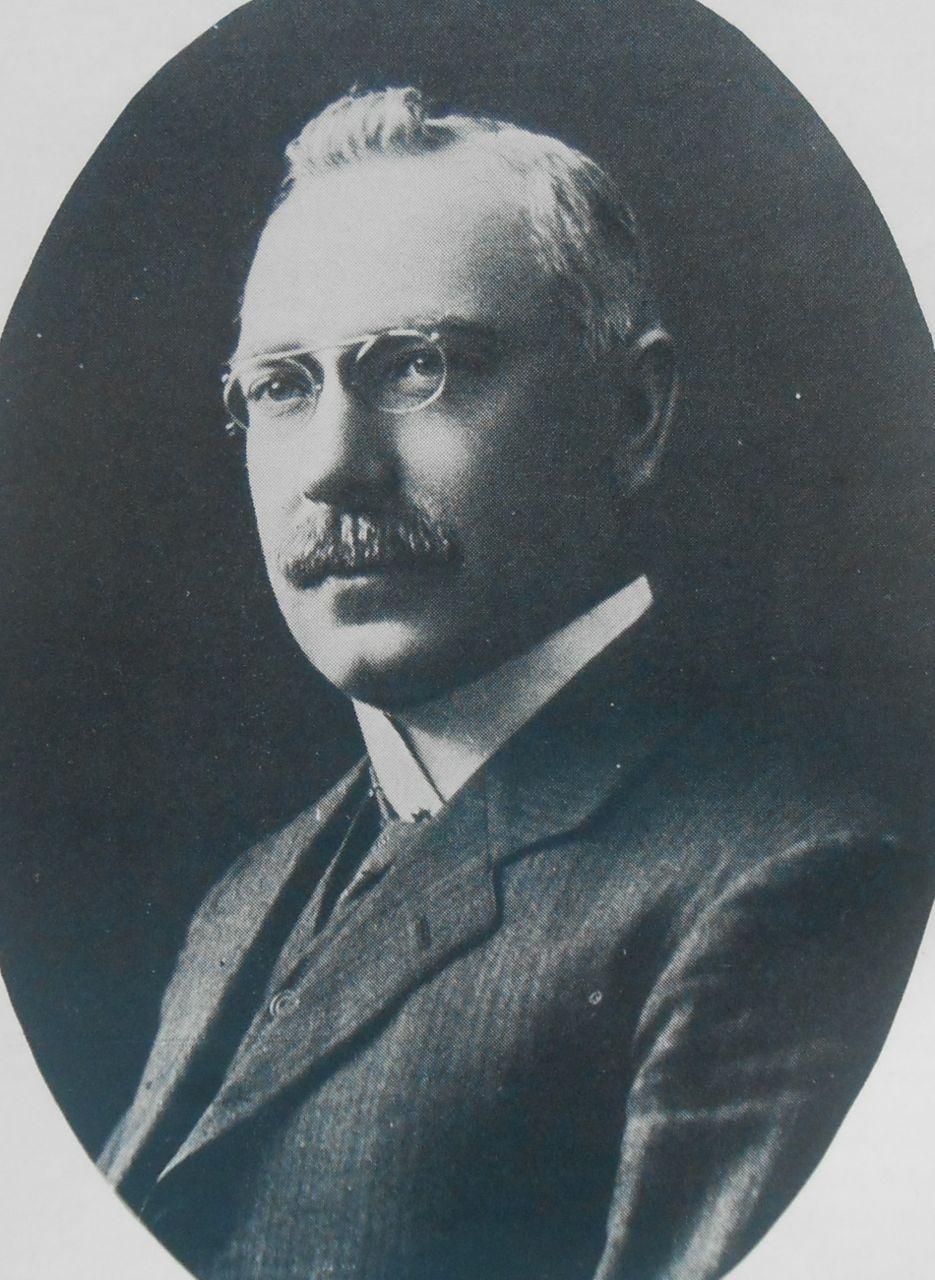

Sir William Hoy (Railways Magazine)

Personal Details

William Wilson Hoy was born on 11 March 1868, eldest son of Robert and Mary Hoy, a farming family living at Arnot Mill, Portmoak, Kinrosshire, Scotland. The family name is of Irish origin, being the Anglicized version of the Gaelic word meaning ‘heart’ or ‘spirit’. However, it is of interest that the word ‘hoy’ is derived from other sources as well. From the 16th century in Scotland and England it was the name used to describe a large, flat-bottomed barge used, in harbours, for loading and unloading ships and for towing ships into different positions – in other words a ‘tug’.

By a strange coincidence, in 1928, just after Hoy’s retirement in South Africa, a tug was launched, named after him. This ‘hoy’ or tug remained in service in Durban Harbour until 1979, after which it was scrapped in 1982. A 70 cent postage stamp featuring the “Sir William Hoy” was produced by the South African Post Office in 1994.

Sir William Hoy Tugboat (via globalmariner.com)

SIr William Hoy Postage Stamp

Hoy’s formal education was limited to the primary (elementary) grades and, at the age of 12, he began work as a junior clerk in the North British Railway Company in Edinburgh, Scotland. Possibly he did not see sufficient avenues of advancement in Scotland, and in 1889 he was recruited by the Cape Government Railways, immigrated to South Africa and took up employment in Cape Town.

An authenticated anecdote reveals his character. He became convinced that shorthand script and typing would become very important in business and qualified himself in both. He brought his personal typewriter with him to South Africa, and it is thought to be the first ever used in the country. One commentator has jokingly claimed that Hoy was the first and only shorthand-typist to become General Manager of the Railways.

He clearly attracted the attention of his superiors and we know that in 1890, after only a year in their employ, he was invited to attend the official opening of the Cape-Free State line in Bloemfontein. There followed a decade of fairly short-term appointments around the country: in 1892, he was Chief Clerk in Kroonstad, and in 1893 he was promoted to a managerial position in Vereeniging. In 1895 he returned to Cape Town as the General Manager of the Cape Government Railways, then represented that section in Johannesburg in 1896 and was then seconded as Assistant Manager to the Rhodesian railways in Bulawayo. After stints in Port Elizabeth and Kimberley, in June 1900 he was appointed Supervisor of the British Military Railway Network, based in Bloemfontein. He held this position until the conclusion of hostilities and was famous for the speed with which sections of the lines in his area were repaired after having been sabotaged by Boer forces.

In 1901 he married Gertrude Mildred Price, daughter of Sir Thomas and Lady Price. Sir Thomas was Hoy’s immediate superior in the Cape Railway’s management structure. The couple had one daughter, Maudie, who appears in at least one of the photographs of the family on holiday in Hermanus. The family holidayed at Hermanus regularly from about 1903 and always stayed at the Marine Hotel, never buying a holiday home and never renting holiday accommodation elsewhere. There are a number of photographic records of the family in Hermanus.

In 1904 Hoy was appointed Chief Traffic Manager of the Central South African Railways, which was formed out of the Orange Free State and Transvaal railways after the Treaty of Vereeniging. He was instrumental in integrating these two sections with each other and then integrating them with the Cape and Natal railways. In 1910 he became the first General Manager of the SAR.

In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I the British Government requested South Africa to initiate military action against German forces in what was then German South West Africa (“GSWA” - now Namibia). Details are given later in this article. Generals Botha and Smuts personally insisted on the appointment of Hoy as director of military railways, with the main task of managing the construction of more than 250kms of new track into GSWA (including 20kms of sidings) under severe time constraints. This was achieved with time to spare and the South African campaign was entirely successful. For this work, Hoy was knighted and made a Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath in 1918.

Sir William Hoy in World War I uniform

Hoy was now regarded as one of the finest strategic thinkers in South Africa, as well as an organiser of formidable talent and he began to be involved in political events. In 1919 he accompanied Botha and Smuts to the Versailles Peace Conference to advance South Africa’s interests. During this visit he received the Belgian Ordre de la Couronne and was created a Knight of Grace of the Order of St. John. He regularly represented South Africa at conferences of countries belonging to the British Empire and was present at the 1926 Conference, when South Africa became a ‘dominion’ within the British Empire.

In the 1920s Hoy continued to develop the railway network in South Africa and to contribute to the industrialisation of the country. He was dragged into politics once again when Smuts called on his help with moving soldiers and materials during the 1922 Rand Rebellion. Sir William retired from the South African Railways in 1928 due to ill-health, and, after only a brief period of illness in Hermanus, died on 11 February 1930. He is buried at the summit of Hoy’s Koppie in Hermanus. His wife who died in the United Kingdom in 1935 is buried alongside him.

In 2015 more details of the grave came to light. The granite headstone on Hoy’s grave was damaged by vandals and the Municipality as the responsible authority asked the Hermanus History Society to ensure that the repairs were properly done. To do this the granite headstone had to be moved to one side, revealing the surface of the grave for the first time in 85 years. We had been prepared to see a fairly rough hole, as we knew from records that rocks had been blasted by explosive to create the grave. However, two examples of high levels of preparation were obvious. First, within the hole blasted in the rock a concrete box had been constructed to provide a regular space as a tomb. Secondly, the box had been filled with beach sand, which is not to be found on the Koppie and would have had to be carried up by hand by the ghillies. Hoy’s coffin must rest securely under metres of this sand.

Activities during the Anglo-Boer War

Railways were a key factor in this conflict and control and use of them was a large part of the reason for British success. This was clear to the British Army from the outset and its expert in such matters was immediately brought to South Africa.

He was Major E Percy Girouard who was at the time head of the railways in Egypt. Girouard promptly set up a management structure for military use of the railways, which linked at each level with the civilian structure. His aim was to keep both elements operating wherever possible. Within the military structures responsibilities were divided around function: security of the tracks, leading eventually to the famous ‘blockhouses’; repair of bridges, tracks and tunnels; transportation of personnel; transportation of materials and so on.

Witkop Blockhouse south of Johannesburg (The Heritage Portal)

Hoy remained in the civilian side of the management structure, but we do know that he accompanied some of the teams repairing the track. However, his main task was integrating the civilian and military uses of the railways and in this he was highly successful. A noted railway historian comments as follows:

No greater proof of Colonel Girouard's appreciation of civilian help could be adduced than the appointment of Mr. Hoy, of the Cape Government Railways, to be traffic manager of the Imperial Military Railways, and no words can convey an idea of the help rendered by the Cape Government Railway to the military authorities in all emergencies. Whatever requisitions were made “and they were large and constant, often causing great inconvenience to the department”, they were cheerfully given, whether it was in the services of the staff or supplies; military requirements being paramount.

Modder River Bridge destroyed during the War (South African Railway Magazine - February 1908)

Challenges at the Cape Government Railways (CGR)

At the CGR Hoy faced three main challenges. First, he had to take a position on the issue of the ownership of railways in general, and the CGR in particular. There existed a strong body of opinion that railways should be privately owned, and operate under regulations set by government. They should not be operated by government, as the bureaucracy involved would inevitably stifle innovation and hinder cost containment. Hoy and others believed that government should own and operate railways, as it would be under pressure to offer the service wherever it was needed and not just where it was profitable. In this case, Hoy's views prevailed, partly because he regularly maintained cost-effectiveness and range of services at least as well as any private operator might.

Secondly, the issue of the gauge of railway had to be decided and implemented, with agreement from the Natal and the two Boer Republics. Without this agreement costly trans-shipping to trains running on a different gauge would hamper all efforts to extend the system. Hoy managed to broker this agreement.

Finally, several different lines had been started under local initiative within the Cape and these had to be integrated into a single system. Hoy was successful in this as well.

Integration of four Railway systems into South African Railways

After Union in 1910 Hoy was entrusted with the even greater task of integrating the four different railway systems in South Africa. He was appointed the first General Manager of the newly-named South African Railways. He proceeded on the basis of a few principles:

- The SAR must be run on business principles and wherever possible at a profit

- It would be uneconomic to try to build rail connections to smaller towns and villages. Rather, ‘railheads’ would be established at key junctions and a road transport system created to take goods further. (In the case of Hermanus the railhead was at Bot River and the first railway bus to the town ran in 1912.)

- Wherever possible electric traction should be employed.

The GSWA Campaign

On Tuesday 4 August 1914 Great Britain declared war on Germany. Three days later, the British Government officially requested South Africa to invade GSWA and destroy the wireless communications stations along the coast, which were a vital part of the German naval activity in the southern Atlantic. Politically, this was not an easy decision for Prime Minister Louis Botha as many Afrikaans-speaking citizens still had strong negative attitudes towards the British and there was considerable political risk involved. In fact, the decision precipitated the Rebellion of 1914, led by General Manie Maritz.

General Jan Smuts chaired a meeting to plan the invasion on 21 August 1914. Those present were Smuts, four army generals and William Hoy, at that time General Manager of the SAR. Hoy left the meeting with the task of constructing 250kms of railway line across virgin territory, in difficult desert conditions, harassed by Boer Commandoes, within as short a time as possible. It is not feasible to give an account here of how this was successfully achieved, but Hoy employed traditional and innovative techniques. He selected the best professional for each aspect of the task, notably Arthur Tippett, Engineer-in-Chief for the SAR. He created a ‘just in time’ process of delivery of materials so that as each shift went on duty their material arrived, but did not block the railway in the interim. (Work was divided into 3 shifts of 8 hours each.) He encouraged and authorised innovative methods, such as laying the rails on the desert surface when this was judged possible and filling in between and around the sleepers at a later stage, once the troops and material were not so urgently needed. He also devised a set of lights on a truck on the rails to allow working at night.

In 1916, the Rand Daily Mail commented: “That Sir William Hoy well deserved the knighthood that has been conferred on him will be admitted by all who have any idea of the immense of work which fell to the lot of the Railway Authorities in this country in the past sixteen months.”

General Botha, as Commander-in-Chief sent a telegram: “General Botha telegraphs appreciating excellent services and sends congratulations on success attained railway construction."

But possibly his greatest success was a campaign he managed himself. He issued repeated orders to all Railway employees to collect all material that might be used in making new rails and to send this to De Aar for sorting, repair and re-use in the GSWA initiative. There was a massive response to this communication, and to others Hoy sent out personally. ‘Eventually 152 miles of rails, 360 000 sleepers and 459 sets of points’ were sent in. A beneficial side effect was ‘a universal clearing up of all lines and depots on a scale beyond anything previously attempted....’

We should bear in mind that Hoy had a few other things going on at the same time as the railway into GSWA. In fact, 16 other railway lines were being constructed under his control at the same time and, in terms of distance, the GSWA line constituted only 23% of the lines under construction. Hoy was knighted for this work and, interestingly, is the last South African to receive a knighthood, before the ban on such awards was legislated by Prime Minister Hertzog in 1924.

Supply Train for GSWA Campaign (McGregor Museum)

The Hoy family home in Johannesburg

The suburb of Parktown in Johannesburg dates from 1893 when the very rich ‘Randlords’ families moved from Doornfontein to land on the edge of a rocky ridge, north of Johannesburg itself and with a fine view further to the north. The area was known to the local farmers as the ‘Witwatersrand’ or ‘ridge of white waters’, as many streams originated along the ridge and then, depending on whether the stream was to the north or south side of the ridge, flowed into the Crocodile or Vaal River tributaries.

A few families had settled before the arrival in South Africa of a railway engineer and soldier from Canada, Captain Henry Smith Greenwood. He arrived in 1900 to take charge of the Imperial Military Railways in the Transvaal during the Anglo-Boer War. In 1901 he built a house in Parktown for his family and called it ‘Wanooka’. He stayed there until 1908 before returning to Canada and the house was acquired by the SAR as the official residence of their General Manager.

Wanooka restored by KPMG (The Heritage Portal)

The name remained something of a mystery until I carried out research to establish its meaning. It appears that Captain Greenwood’s family lived in a town in Canada called Lakefield, in Ontario. The lake referred to is named by the First Nation Ojibwa people as ‘Katchewanooka’, which translates as ‘lake of sparkling waters’ or ‘lake of many rapids’. It is reasonable to conclude that Greenwood realised the similarity between the name of the Canadian lake and the name of the ridge of white waters on which his South African house was built.

In 1910 the Hoy family moved into the house, when he was appointed General Manager of the SAR. At that stage, a second storey had just been added to the original house. The basic design was described in a report commissioned as: “a square single-storey home, with a front veranda and a back stoep, and a generous, interleading dining room and sitting room, a study and library, four bedrooms, one bathroom, and kitchen and pantry…”

Though Hoy was often absent on business and spent every annual holiday in Hermanus, the family obviously liked the house, as Hoy bought it from the SAR in 1920. It was sold after his death in 1930 and passed through several hands until, in a very dilapidated state, it was bought by the company Hunt, Leuchars and Hepburn in 1980. The company renovated Wanooka according to the best information available, using it as its entertainment facility, and building a modern office block behind the house. Early in the 21st century the property changed hands again and the new owners KPMG carried out another renovation, restoring the house to its original condition.

Electrification of the Railways

Hoy was a strong advocate of the electrification of railways and, as early as 1922, wrote a long article on the topic that was published in the South African Railways and Harbours Magazine. However, the railways could not be electrified unless an adequate electrical supply was available – and this was not yet the case in South Africa. This fact opened up a line of co-operation between the Railways and the relatively newly-established Electricity Supply Commission (which had the English acronym ‘Escom’ until 1987). Specifically, Hoy was involved in two projects that are amongst the earliest recorded: the electrification of the Cape Town-Simonstown route in 1927 and the construction of the Congella Power Station in 1928.

However, the groundwork had been laid much earlier. In 1917 Hoy had invited experts on electrification from Great Britain to assess the South African system and advise him on the issue. The delegation and the South Africans designated to travel with them were given the use of Hoy’s own private railway carriage during their stay. Their report was received in 1920 and immediately acted on by the government advised by Hoy, resulting in the creation of Escom in 1923.

At this time Hoy was interviewed by a well-known American journalist, Isaac F Marcosson, who was writing a book on Africa. The comments Marcosson makes are worth quoting at some length:

Stimulating the railway system of South Africa is a single personality which resembles the self-made American wizard of transportation more than any other Britisher that I have met with the possible exception of Sir Eric Geddes, at present Minister of Transport of Great Britain and who left his impress on England's conduct of the war. He is Sir William W. Hoy, whose official title is General Manager of the South African Railways and Ports. Big, vigorous, and forward-looking, he sits in a small office in the Railway Station at Cape Town, with his finger literally on the pulse of nearly 12,000 miles of traffic. During the war Walker D. Hines, as Director General of the American Railways, was steward of a vaster network of rails but his job was an emergency one and terminated when that emergency subsided. Sir William Hoy, on the other hand, is set to a task which is not equalled in extent, scope or responsibility by any other similar official.

Like James J. Hill and Daniel Willard he rose from the ranks. At Cape Town he told me of his great admiration for American railways and their influence in the system he dominates. Among other things he said: "We are taking our whole cue for electrification from the railroads of your country and more especially the admirable precedent established by the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway. I believe firmly in wide electrification of present-day steam transport. The great practical advantages are more uniform speed and the elimination of stops to take water. It also affords improved acceleration, greater reliability as to timing, especially on heavy grades, and stricter adherence to schedule. There are enormous advantages to single lines like ours in South Africa. Likewise, crossings and train movements can be arranged with greater accuracy, thereby reducing delays. Perhaps the greatest saving is in haulage, that is, in the employment of the heavy electric locomotive. It all tends toward a denser traffic.

"Behind this whole process of electrification lies the need, created by the Great War, for coal conservation and for a motive power that will speed up production of all kinds. We have abundant coal in the Union of South Africa and by consuming less of it on our railways we will be in a stronger position to export it and thus strengthen our international position and keep the value of our money up."

Since Sir William has touched upon the coal supply we at once get a link, —and a typical one—with the ramified resource of the Union of South Africa. No product, not even those precious stones that lie in the bosom of Kimberley, or the glittering golden ore imbedded in the Rand, has a larger political or economic significance just now. Nor does any commodity figure quite so prominently in the march of world events.

The creation of Escom enabled Hoy to press ahead with a joint venture between Escom, the Durban Municipality and the SAR to build a power station at Congella, just outside Durban, to supply power for the city, but also for the trains hauling coal from Glencoe in northern Natal to Durban. The station was built on 8 hectares of land supplied by the Railways. Further investigation and experience, however, showed that it would be more economical to build a power station nearer the coalmines. The town of Colenso, on the Tugela River, was selected and, with Hoy behind the project, the work was completed in two years. At the time it was the second biggest railway electrification project in the world, with only the electrification of the railways in Chicago being larger. Hoy continued to support electrification of railways throughout his life.

The Rand Revolt of 1922

Hoy showed his adherence to Smuts during this episode of labour unrest. Sharp differences between the owners of mines and the -largely European and mostly British – workforce, created a showdown of almost military proportions. Smuts (as Prime Minister) took personal command of the situation and decided that force had to be used. He mobilised the military forces in Johannesburg, used artillery and even ordered the Air Force to bomb areas of the city held by the miners. However, the situation still could have got out of hand if Hoy had not re-organised the entire railway schedule to assemble and run several trains of military reinforcements from Durban.

It is perhaps useful to mention here that the working relationship between Smuts and Hoy was reinforced by a shared affection for Hermanus. Smuts' presence in Hermanus goes as far back as the late 1890s, when he often visited his sister who was married to Dr. Joshua Hoffman who built and ran the Sanatorium (now the Windsor Hotel). While Hoy’s association with the town ended with his death in 1930, Smuts continued to visit until the late 1940s. Another of his sisters, Bebas, was Mayor of Hermanus during World War II and he could always rely on the support of P John Luyt, owner of the Marine Hotel.

Tourism and the Kruger National Park

In 1922 Hoy became interested in the Kruger National Park – or the Sabi Game Reserve as it was then called. He was consistently trying to increase tourism to South Africa and had instituted a ‘round in nine’ tourist train trip, from Johannesburg, through the then Eastern Transvaal and to Lourenco Marques (Maputo). On the return trip an overnight stop was included at a place in Sabi called ‘Reserve’. It is now known as Sabi Bridge. Travellers were able to leave the train, enjoy a ‘braai’ around campfires, listen to tales told by the game rangers and then sleep comfortably on the train. A history of the Park recounts the response:

The passengers declared this the most exciting and interesting episode of the whole tour, and immediately the Game Reserve began to be recognised for the tourist attraction that it was.

Col. Deneys Reitz became an enthusiastic advocate of the National Park scheme and so did various other prominent personalities such as Sir William Hoy, the General Manager of the Railways, who requested Stratford Caldecott, an artist, to be the Railways publicity agent for the advertisement of the Sabi Game Reserve as a potential asset. Caldecott was also an enthusiastic writer and after spending two months in the Reserve, his influence in South Africa was such that soon there was hardly a man, woman or child in the country who had not heard, or read, or seen pictured some aspect of the Sabi Game Reserve.

After this initial contact Colonel Stevenson-Hamilton and Hoy continued to work together. In 1927 the SAR and the Park reached an agreement on the overall strategy to attract tourists to the Park. In this agreement the SAR through Hoy, undertook to ‘provide all transport, by rail and road, and to launch advertising campaigns and catering services and to pay the (Parks) Board a percentage of the income received’. The Board of the Park agreed to build roads, rest huts and other facilities and to provide guides and protection services. Co-operation continued between the SAR and the Parks Board well after Hoy’s retirement, but he remains the one person who saw the tourist potential of the Game Reserve and acted effectively on it. His backing (and through him the backing of the SAR) was decisive in countering the proposals being made to de-proclaim the Park in the period 1922-1926.

Hoy and the Wanderers Club, Johannesburg

The Wanderers Sports Club was established in Johannesburg as early as 1888, on land to the north of the city, on the farm Braamfontein. It had a very successful start and many of the Randlords and their families joined and participated in sporting activities or came as spectators to important events. International cricket matches were played on the main sports field, although it was for many years not grassed.

Wanderers Stadium from above

However, after World War I the Club began to struggle. The railway station had been built immediately adjacent to the sports fields, the commercial activities of the city had expanded around it and most of the wealthier members had moved to Parktown, to the north of the Club. The financial standing of the Club fell, as did membership, and, by 1922 the violence associated with the miners’ strike made it dangerous to use the facilities, on occasion.

In 1924, the SAR specified which portion of the Club’s grounds it wished to acquire for expansion and it was understood that the Club really faced the choice between sell or have the land expropriated. The official History of the Club has the following passage:

The Club struck the attitude that a Sports Ground was as important as a station and strong words were uttered. Schoolchildren had free use of its facilities, its grounds were host to innumerable visiting teams who improved the standard of almost every sport, and it was the nursery of the country’s champions and the joy of the citizens, quite apart from its titles at the hands of President Kruger and Lord Milner.

Sir Julius Jeppe, a figure of great stature in the affairs of the community, and Victor Kent were in constant colloquy with Club and Railway officials, notably Sir William Hoy, the general manager, seeking to temporise and conciliate and find a way out of the difficulty. There was none and public opinion began to harden against the Club’s apparent opposition to the progress of the town.

On the 25th September 1925, a special meeting was held to settle the matter. Nearly 100 members, including founders such as Gustav Sonn, Bernard de Malraison and C. A. O. Bain, attended and heard Kent present the case in a lengthy address in which he counselled that it was better to accede to the Railway demand for 100 feet in depth of ground along about 200 yards of Hancock Street with appropriate compensation than, by refusal, force expropriation.

Once again, specific mention is made of Hoy as a negotiator. However, in this case, the Club only obtained a stay of execution. In 1945 the SAR bought the remaining land and buildings at an agreed price and the Club moved to a site that was then regarded as ‘in the country’, in the suburb of Illovo, where it has generally prospered.

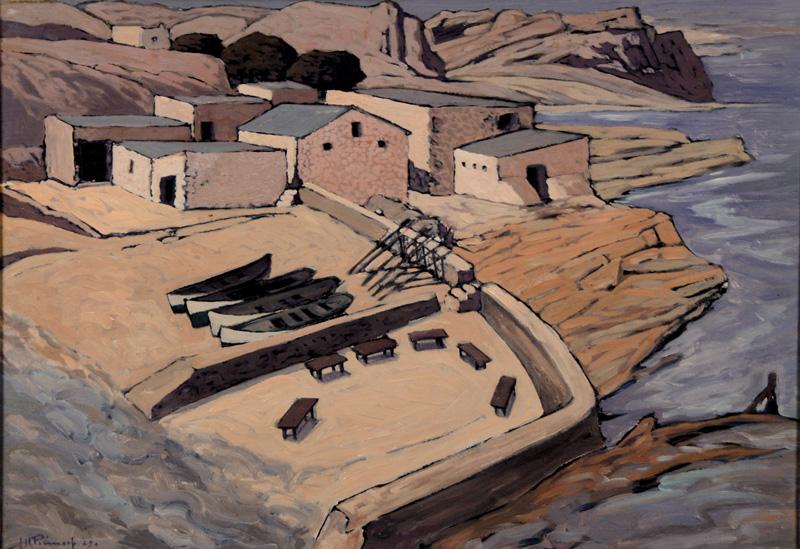

Hoy, Pierneef and the Johannesburg Station Panels

In 1929 the famous South African landscape artist J H Pierneef was commissioned by the South African Railways and Harbours to paint 32 panels for rooms in the new Johannesburg Station. This occurred after the retirement of Hoy in 1928, but there is no doubt that he had a large say in the choice of artist and subject matter. In fact, one of the panes depicts the Old Harbour in Hermanus, a subject that was not of national significance, but was of great concern to Hoy. Also, it would have reflected Hoy’s own tastes in the bushveld scenes, though these were, of course, a major interest of the artist’s as well. Each panel is about 150cms by 140cms and Pierneef was paid the princely sum of R80 for each panel. An art history source comments on the importance of the work:

This project created enormous publicity for the artist, as the Railways were responsible for the promotion of tourism both nationally and internationally, and Johannesburg Railway Station became the main point of embarkation for visitors, whether tourists or businessmen, as the age of air transport had yet to arrive. The ‘Station Panels’ were installed by the end of 1932, and included four smaller panels of indigenous trees.

The Panels are now in the Rupert Museum in Stellenbosch.

Pierneef Panel - Old Harbour Hermanus via Travel And Trade South Africa

Conclusion

Hoy’s rapid rise to senior positions and his influence beyond strictly railway matters is directly attributable to being the right person in the right place at the right time. Railways arrived somewhat belatedly in South Africa, demanded by the diamond and gold industries. But the effect was the same as in many other countries: the growth of the railways propelled individuals to prominence because of the economic and social impact of the technology itself.

Historians of the railways such as Wolmar identify at least three major impacts of the process. The railways had an economic impact in reducing the costs of transport of goods and accelerating the journey to market and making it possible to link different markets:

…in all countries where the national railway system…has succeeded in creating a network from end to end of the territory, the railway has at once become a source of economic strength to the whole nation, not merely to a locality.

The construction of railways created employment and investment and a demand for goods not previously produced. Every level of commerce and industry had to negotiate with the railway authorities to ensure that its interests are met. This makes the individuals in Railway management well-known and influential.

Railways also had a political impact. The most visible element of this is the debate that had raged in every country concerning ownership of the railways. Hoy and many others strongly maintained that the railways were a social service that should be accessible to all citizens and thus should be owned by the State. Opposition came from those who argued that State ownership will inevitably result in a bureaucracy managing the service, with consequent higher costs and lower level services than would be provided by private railway companies. No country has satisfactorily resolved this dilemma.

Finally, in South Africa and many other countries railway construction was seen as part of nation-building and the higher levels of railway management as political posts, with the responsibility for ensuring that the benefits of railway connections are supportive of nation building – or, in the case of Cecil Rhodes, of empire –building.

Without in any way diminishing Hoy’s competences, we must realise that the dynamics of the spread of the railways in South Africa in the 30 years of his career helped to promote his career. So also, did his chancing on Hermanus.

For a number of reasons Hermanus in the period 1900 to 1950 was historically a place in time and space that attracted women and men of national and international standing. In turn, these figures had a variety of attitudes to Hermanus, ranging from fading memories of a single beach holiday to committed relationships, sustained over lifetimes. Through Hermanus, Hoy had links with all the Governors-General of his time, with influential politicians and, above all, with Smuts. His strength lay in the fact that he combined a strong visibility in Hermanus with a high level career in an important sector of the South African economy during times of conflict, reconciliation and rapid growth.

These ideas are speculative since, as far as I know, Hoy did not leave any writings about his experiences in Hermanus or why he returned at least annually for nearly 30 years. However, he did return regularly and always stayed at the Marine and always went fishing. He created good relationships with his staff, especially Danie Woensdreght, though I suspect these were of a patriarchal nature. He could bend the rules, as when he made railway staff available to the Marine Hotel when high level guests were visiting. He moved easily in high society, both civilian and military and was politically astute. He embodied the favourite Victorian story of ‘local lad makes good’, though he did have to emigrate to do it. He should feature prominently in everyone’s understanding of the history of Hermanus and South Africa.

Dr Robin Lee retired to Hermanus in 2001 after a career in the academic world and working in NGOs. In 2003 he started the University of the Third Age in the town and is involved in teaching and administrative work on a voluntary basis. In 2012 he joined a group that wished to formalise the study of the history of the area. This group is now known as the Hermanus History Society. Click here for details of the activities of the Society.

References

- Anon: 150 Years of Rail in South Africa: S A Rail, Vol.47, No.3, October 2009

- Burman, Jose: Early Railways at the Cape (1984)

- Burman, Jose: Hermanus: a Guide to the ‘Riviera of the South’ (1989)

- Carruthers, Jane: The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (1995)

- Du Toit, S J: Hermanus Stories I (2005)

- Du Toit, S J: Hermanus Stories II (2006)

- Du Toit, S J: Hermanus Stories III (2007)

- Du Toit, S J: Whale Capital Chronicles I (2004)

- Du Toit, S J: Whale Capital Chronicles II (2007)

- Greenwood, Captain Henry Smith: ‘Wanooka is Grand Again’: www.joburg.org.za (14 July 2015)

- Gutsche, Thelma: Old Gold: The Story of the Wanderers Club 1888-1968

- Haarhoff, Johannes: Construction of the Prieska–Kalkfontein Railway Line 1914–15: Civil Engineering Magazine, 2015 (Three parts)

- Heritage Portal: www.heritageportal.co.za

- Hoy family name: http://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Hoy#ixzz3eC4fPBHp

- Hoy stamp: www.shipstamps.co.uk

- Laws, Bill: Fifty Railways that changed the course of History (2013)

- Lee, Robin (ed.): In Those Days: The Story of Joey van Rhyn Luyt at the Marine Hotel, Hermanus (2014)

- Marcusson, Isaac F: An African Adventure (1921)

- Mitchell, Dr. Malcolm: A brief history of transport infrastructure in South Africa: 3 articles: Civil Engineering Magazine, (2015)

- Pierneef, JP: Ama Culture – Art South Africa: www.artssouthafrica.com

- Rand Rebellion 1922: SA History on Line: www.sahistory.org.za/topic/rand-rebellion-1922

- Reynolds, David: A Century of South African Steam Tugs (1992)

- Samson, Dr. Anne: Mining Magnates and World War One: Brenthurst Library, November 2012

- South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, February 1916

- Stelsjkal, John and John Kinahan: “Finding Europe’s Great War in Africa”, Features, Issue 59, June 2008

- Tabor, George: The Cape to Cairo Railway (2003)

- The Bayer-Peacock Quarterly Review, April 1930

- Tredgold, Arderne: Village of the Sea: The Story of Hermanus (1986)

- Wolmar, Christian: Blood, Iron and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World (2009)

- Zurnemer, Major B A: The State of the Railways in South Africa in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902, S A Journal of Military Studies Vol.16, No. 4, 1986

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.