Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Who was the first properly trained engineer to practice in South Africa? There is little in the history of the Dutch occupation to suggest that the minimal infrastructure they provided was carried out by competent officers. Van Riebeeck may indeed have built a primitive jetty and Wagenaar a water tank, but these no doubt were constructed by handy employees of the Company who succeeded by common sense rather than by formal training. Likewise Hendrik van Oldendaal, Simon van der Stel’s head gardener, who is sometimes touted as the first Town Engineer of Cape Town on the grounds that he constructed a “canal” to cut off water from the mountain from the Grand Parade. The Dutch were avid canal builders and imposed their homeland expertise on their colonies; Columbo, Batavia and New York all were blessed with canal systems, but again, these were no doubt constructed by workmen who had learn their trade in the polders. Undoubtedly Cape Town Castle was designed and set out by competent military engineers, but there is no record of their having stayed in the country.

The Castle (The Heritage Portal)

In about 1740 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) decided to lash out and spend money on a mole to protect shipping in the Table Bay roadstead, and the quartermaster Jacobus Moller was instructed to carry out the work. Poor Moller had a hopeless task. He was severely handicapped by constraints on funds (a problem which would crop up time and time again right up until present times), by shortage of materials, and lack of any willing, let alone skilled, labour force, but most of all by his complete ignorance of the principles of harbour engineering. After eight years of desultory work, winter storms took their toll and the entire structure ended up scattered on the seabed. Thus ended the Company’s only serious attempt to provide major infrastructure for the outpost. Perhaps we should not be too hard on Moller as the scientific understanding of coastal engineering was a still a couple of centuries away. However, his efforts are remembered by the name of the headland where he carried out his abortive work: Mouille Point.

Mouille Point on the left (Wikipedia)

Then there was Carel Wentzel. In 1771 he was employed to build a drain along the western edge of the town, the present Bree Street, to cut off runoff from Signal Hill which turned the cross streets in fledgling Cape Town into mud baths. He decided that the material along the demarcated line was too difficult to excavate, and so without authority he moved his canal some 50 metres up the hill. The change of plan was only discovered when the work was complete, so Wentzel was responsible for two “firsts”: the first recorded instance of unauthorised work in the colony, and the first instance of urban creep – the town boundaries had to be extended to include the “outside canal” or Buitengracht as the street alongside is still known.

And so in our search for the first competent engineer who made his mark on the country we come to the undoubtedly talented and properly trained Thibault, whose achievements are still admired today.

Drawing of Louis Michel Thibault by Lady Anne Barnard c1800 (Wikipedia)

Louis Michel Thibault was born at Picquigny near Amiens in France in 1750. He enrolled at the Royal Academy of Architecture and proved to be a brilliant student, winning prizes and being selected to present his design for the coat of arms of the Academy to King Louis XV. Maybe architecture did not suit his adventurous nature, because on qualifying he signed up at the prestigious Corps des Ponts et Chaussees (the School of Bridges and Roads), to study engineering. He then joined a Swiss mercenary regiment raised by his instructor at the school. War clouds were gathering in Europe as France sided with the American colonists in their struggle for independence, so the VOC employed the mercenaries to guard the Cape against possible British invasion.

Thibault arrived at the Cape in 1783. After two years, peace was declared and the regiment's services were no longer required. However, he had seen opportunities at the Cape and so he left the regiment to enter VOC service where he was appointed Inspector of Buildings and Director of the School of Cadets. He also set up a private practice which flourished as a result of architectural commissions from Governor van der Graaff. He became associated with Anton Anreith, a young sculptor and woodcarver from Freiburg, and with Hermann Schutte, a young architect and builder from Bremen. The three collaborated on several prestigious projects including the Lodge de Goeie Hoop which today is part of the parliamentary complex. Groot Constantia homestead is presumed to be his work and he was definitely responsible for the wine cellar behind it. (Anreith contributed the celebrated pediment.) But mainly he set the Cape Dutch style of architecture firmly on the map, either through his own work or through his designs being copied by pupils and colleagues for numerous farmhouses which today grace well-funded wine estates.

Groot Constantia Manor House (SJ De Klerk)

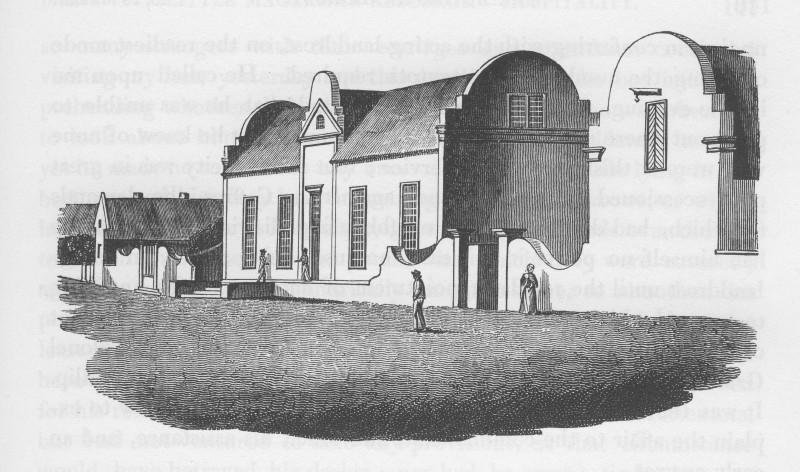

When Britain occupied the Cape in 1795, Thibault lost his post, but his value was recognised by successive Governors. True to his mercenary instincts he changed his allegiance and was given various commissions to provide and restore military infrastructure. When Dutch rule was restored he was again temporarily out of favour but again changed sides and was then made Inspector-General of Government Buildings. In this period he built new drostdys at Tulbagh and Graaff Reinet.

Sketch of the Drostdy, Graaff Reinet (William Burchell)

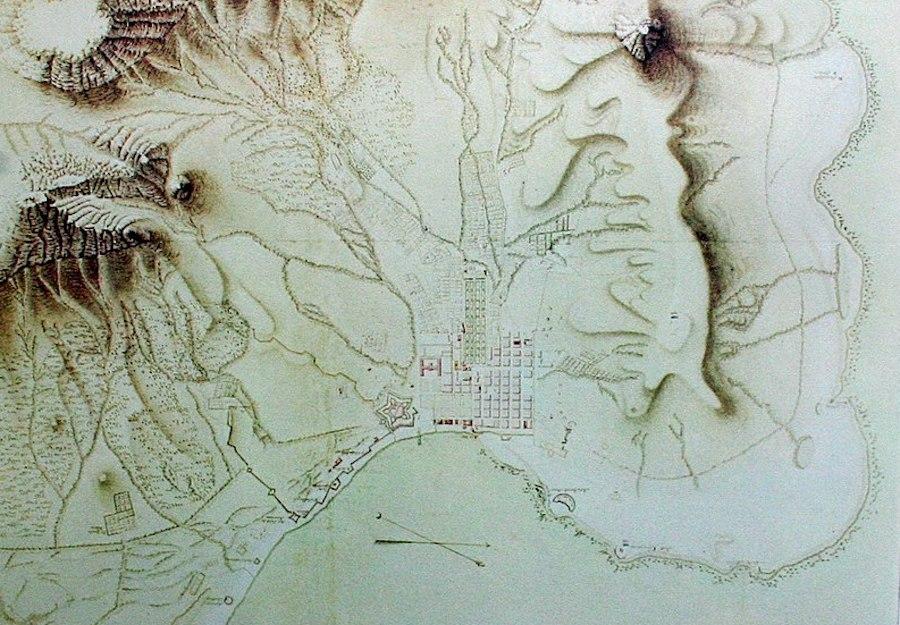

Once more the Cape changed hands and Thibault found himself on the losing side, accompanying General Janssens on his retreat and subsequent surrender to the British. Once more he lost his post, and once more the authorities found that they could use his expertise and restored his position. But the Governor, Lord Charles Somerset preferred the Georgian style of architecture to Cape Dutch, and so his popularity as designer of buildings waned. But his skills as an engineer and surveyor were still in demand. In 1807 he was appointed to report on the feasibility of a new main road from Rondebosch to Muizenberg and subsequently he was given the job of supervising survey and construction: this was no easy task as property boundaries were unregistered and indistinct, and no doubt required much adjustment and negotiation with owners. The alignment he decided on still exists as the main road through the Southern Suburbs. Two significant river crossings were necessary and Thibault designed appropriate bridges. The stone abutments of the Liesbeek crossing still stand, clearly visible from the subway leading to Newlands rugby ground, although the timber deck has long been superseded by a modern concrete structure.

Recently Cape Town Municipality decided to upgrade the culvert carrying the Diep River under Main Road near Plumstead. The plan was to completely replace an existing stone culvert of inadequate capacity. However, a conscientious young engineer noticed that the old culvert could well be of historical interest and called in a heritage consultant who confirmed that the little stone bridge was in all likelihood the work of Thibault, dating from about 1811. This gave rise to some excitement. Was this the oldest working bridge in the country? However, a sketch by the artist Bowler shows the structure with a timber deck resting on stone abutments in the usual Thibault style, so it appears that the deck was replaced by a barrel arch, probably by Michell in about 1845. Nevertheless, the old bridge has been retained with Thibault's abutments clearly visible, and a new culvert has been tastefully installed beside it, with a plaque to describe its history.

The first major bridge in the country is reported to be the "Oubrug" which was built in 1811 across the Palmiet River downstream of Grabouw. All traces have since disappeared, but apparently it was a substantial multi-span structure of masonry piers and timber deck. It is reasonable to suppose that Thibault, as the most senior and most skilful engineer in the Cape at the time was responsible for its design – it was certainly a larger version of his other bridges.

Like many of his contemporaries Thibault was a competent artist, although his drawings show the distinct influence of his architectural draughtsmanship.

Thibault married Elizabeth van Schoor, daughter of an old Cape family in 1786, and they had four children. The only boy died in infancy and so the Thibault surname has not survived in South Africa, although our first proper engineer is celebrated by the several roads, squares and buildings which have been named after him.

Thibault died in Cape Town on 15 November 1815 as a result of pneumonia contracted while surveying. His heritage is still appreciated and enjoyed.

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.