Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The series on the History of Southern African Railways continues with this piece on the mighty Garratt engines that conquered the geography of the sub-continent. The article is a must read for any railway enthusiast!

The Highveld plateau of southern Africa which rises sharply from the narrow coastal plains means that most of the sub-continent is higher than 1000 metres (3 280 feet) above sea level. This topography hampered the exploration and development of the hinterland as the escarpment proved to be a barrier to those who lived along the coast. Passes would in due course be made allowing hunters, missionaries and above all farmers, to make their way up to the top of the plateau. A generation after the Great Trek (of 1838) diamonds were discovered (1869), where Kimberley stands today and that was the impetus to be built a railway towards the interior (from 1874 to 1885). Those railway builders would face the same difficulties in finding a way up the escarpment as had the Trek Boers.

The routes taken, by South Africa’s railways (refer to “Ox Wagon to Iron Horse), from the coast were dictated by the inland plateau and it was impossible to avoid the steep gradients which had to be surmounted. The difficult terrain encountered meant that not only were the gradients severe but also “S” curves and horse shoe bends were many. Moreover the permanent way was lightly laid as it was not financially possible to build to the standards of Britain. Paradoxically the discovery of gold in 1886 on the “Rand” soon demanded that huge tonnages be carried by the railways on tracks not designed for the purpose. The limitations of the permanent way were to tax the minds of the railway establishment and although upgrading of the civil works of the system was the long term solution, something was needed in the interim.

At the time of Union, on the 31st May 1910, the colonial railways would amalgamate to become the South African Railways (refer to “New Era Begins). The mainline railway network, as built by S.A.R.’s constituents, was fully developed although in dire need of upgrading. Civil engineering works encompassing bridge strengthening and upgrading of the permanent way (heavier rail sections re-ballasting) was an expensive business and alternatives were therefore sought. The most attractive alternative was to use an articulated locomotive which would have greater power than a conventional tender engine, with no increase in axle loading. There were several types of articulated locomotive on the market and each had its devotees. In South Africa it would come down to just a two (iron) horse race, between the Mallet and the Beyer-Garratt.

David E. Hendrie, the first Chief Mechanical Engineer (C.M.E.) of the S.A.R. (1910 to 1922), had introduced locomotives to his specification that were built overseas, predominately in Britain. By early 1921, a trial was deemed necessary to pit three classes of locomotive against one and other. It would take place on the Natal main line, between Durban and Ladysmith, one of the most severe on the Cape Gauge (3’-6”) in all of Africa, where gradients were as steep as 1 in 30 and curves as tight as 4½ chains radius (just under 300 feet).

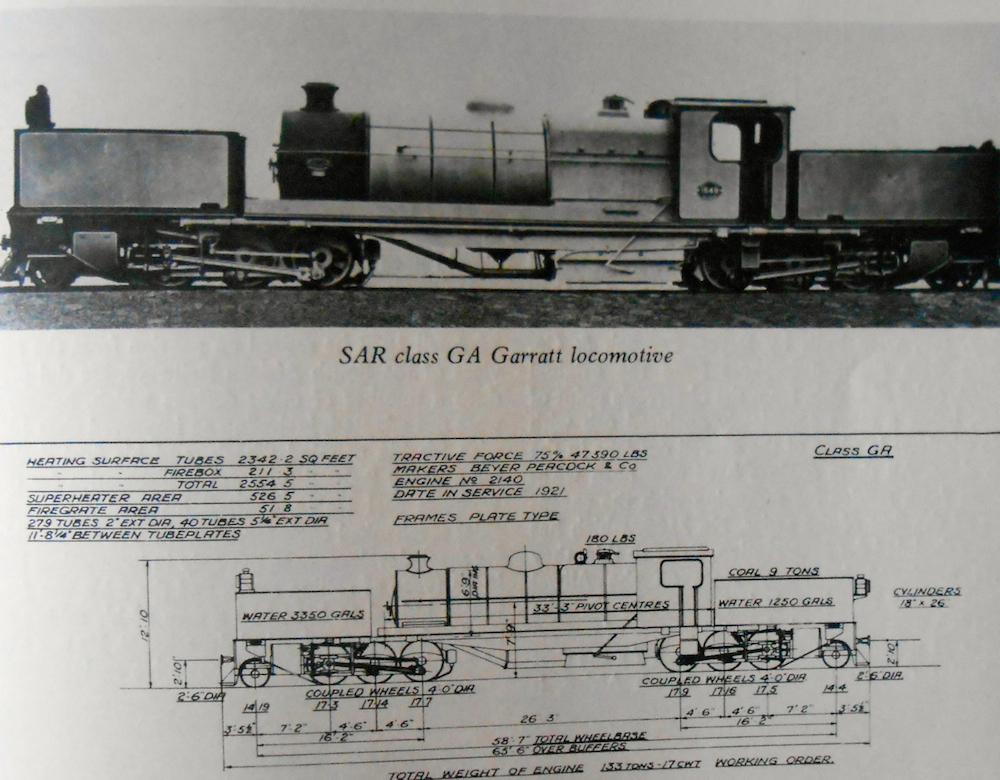

The Trial (or comparative test) was to be between a class 14B 4-8-2 tender engine, a Mallet class MH 2-6-6-2 and a Beyer-Garratt 2-6-0 + 0-6-2. The latter No. 1649, had only recently been delivered from the makers - Beyer Peacock, Manchester, England.

SAR Class GA Garratt locomotive (Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways)

The stage was set and the first tests were carried out under the direction of an enthusiastic young locomotive engineer, by the name W. Cyril Williams. His test report was forthright and made it plain that the Beyer-Garratt was superior in all regards. This ruffled the feathers of his superiors who were more familiar with the two other types (14B MH) and further tests were called for, which only confirmed the original findings.

The tests of 1921 were a triumph for the Beyer-Garratt articulated principle and they were no less so for the W. Cyril Williams, whose eagerness from the very outset had been a little too brash for his superiors. However his report and his zeal had not passed unnoticed by No. 1649’s manufacturer - Beyer Peacock and he was soon offered a position as their “London Representative”. Before long he became something of a legend as a super salesman for the export orders that he secured and was known to all in the industry as “Garratt Williams”. The only market that he could not crack was North America where they stubbornly held onto the Mallet locomotive. His crowning honour was to become President of the Institute of Locomotive Engineers.

Now what is a Beyer-Garratt locomotive? To start with the name comes from the manufacturer and its inventor, The Beyer part refers to Beyer Peacock and the Garratt to Herbert William Garratt (1864-1913), who approached Beyer Peacock with his rough idea for an articulated steam locomotive. They saw the possibilities and worked on the details and patented the design in 1907.

The Beyer-Garrett steam engine comes nearest to the ideal of an articulated locomotive than any other type and the idea came to Garratt whilst he was watching a bogie well wagon, loaded with a large boiler, traverse the sharp curves in a Scottish works yard.

The Beyer-Garratt differs from a conventional locomotive in that its boiler is not directly over the engine (chassis, wheels and motion), instead the boiler (cab) is mounted on a sub frame which is slung between the two engine sets which are allowed to pivot making the wheel base less rigid. On the front engine (chimney end) sits the water tank and on the rear engine sits the fuel bunker (coal/oil/wood).

The Beyer-Garratt’s main advantages may be summarized thus :

- A Beyer-Garratt with one crew can replace two double headed tender locomotives with two crews, e.g. one GM (built 1938) could replace two 19D tender engines with no loss in power output.

- The geometry of the design allows the boiler unit to move inwards when traversing a curve (like a bowstring in a bow) and this reduces the centrifugal force allowing faster running (and less chance of overturning).

- The longitudinal spacing of the engine units gives a low figure for weight per foot run of wheelbase, permitting a Beyer-Garratt to cross restricted bridges of light construction and run on lightly laid track (60 lb/yard). NB: Main line tracks in Britain are laid with 110 lb/yard rails.

- It is a good steam raiser, as a very large diameter boiler with a short length (thus short tubes) and large firebox can be easily incorporated as it is carried clear of all the parts of an engine such as wheels and motion.

- Since the Beyer-Garratt runs equally well in either direction, turntables are not required.

- On sections with many tunnels, where trailing smoke is liable to obscure the cab view or make the cab uncomfortable the engine can run cab first.

Unfortunately H.W. Garratt did not live to see the success of his invention as he passed away at the age of forty-nine, in 1913, the year before the Great War and it was therefore left up to the engineers and drawing office of Beyer Peacock to develop his concept.

Railway Engineers around the world followed railway matters avidly through technical papers and magazines and the British private locomotive builders had active sales departments that advertised their products through the technical press. Therefore it was not long before the word got out that there was a new type of locomotive which could increase pulling power without increasing axle load. The Beyer-Garratt was the answer to a maiden’s prayer and Beyer Peacock were “in the pound seats”.

The Beyer-Garratt Steam locomotive was well suited to Southern African conditions and from the 1920’s through to the 1950’s Beyer Peacock’s order book was full with orders from S.A.R. Rhodesia Railways, the Benguela Railway (Angola) and the East African Railways. In fact at times they were hard pressed to meet supply dates and other locomotive firms stepped into help and built the type under licence, notably North British and Henschel.

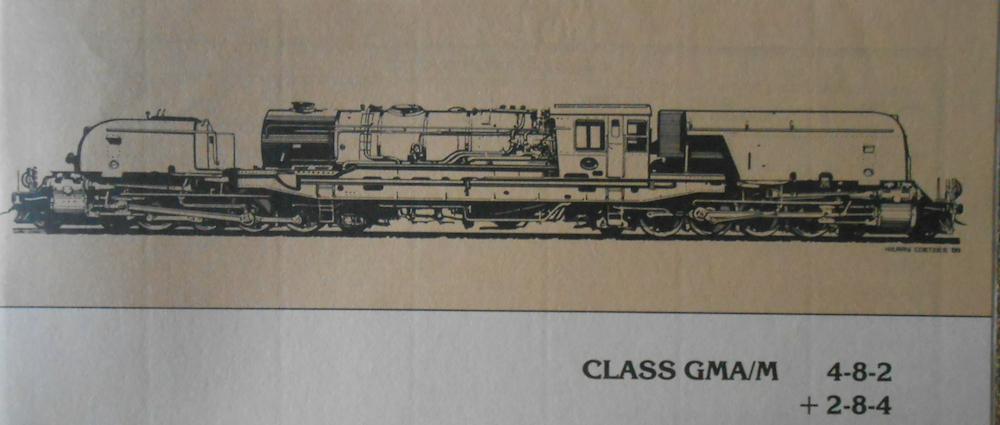

South African Railways were the largest user of the type not only on the Cape gauge but also on the 2’-0” narrow gauge (610 mm), with 400 units being supplied of several different classes; the largest class, numerically, was the GMA/GMAM with one hundred and twenty being built, between 1952 and 1958, in batches shared between Beyer Peacock (58), North British (32) and Henschel (30).

Another railway to rely on the Beyer-Garratts was the East African Railways which was a unification of the Kenya Uganda Railways and the Tanganyika Railways after the Second World War and it operated from 1948 until 1975 (when the E.A.R. was dissolved). The E.A.R. ran not on the Cape gauge (3’-6”) but on the Metre gauge (3’-3 3/8”), a legacy of German colonial rule in Tanganyika before the First World War and Kenya receiving surplus railway equipment from the Indian metre gauge system.

Beyer-Garratt locomotive leaving the coastal area with a freight train for Nairobi (Railways of Southern Africa)

The main line from the port of Mombasa to Nairobi (at 5 000 feet above sea level) was first built under the aegis of the Kenya Uganda Railway, a railway built to deter the slave trade. In 1899 the railway reached the site of Nairobi, at that time only a swampy plain devoid of habitation, but destined to become Kenya’s capital and the commercial hub of East Africa. The K.U.R. was originally laid as a military railway with 50 lb/yard rail and was noted for its heavy gradients and many curves; not unlike the “old” line up from Durban. By the 1920’s, as traffic volumes increased, the line had to be upgraded (to 80 lb/yd rails) and re-aligned so as to lessen the gradient to 1 in 60. Upgrading again with 95 lb/yard rails was done in the early 1950’s in readiness for introduction of the E.A.R. “59” or “Mountain” Class which was to become the masterpiece of the Beyer Garratt type locomotive. These powerful “beasts” were ordered in 1954 to the design of William Bulman C.M.E. and were built by Beyer Peacock; thirty four in total. They had a tractive effort (at 85% boiler pressure) of 83 350 lb (37 750 kg), an axle load of 21 tons, a wheel arrangement of 4-8-2 + 2-8-4 and were oil fired. They were built as a result of the backlog of merchandise that had built up at the port of Mombasa which could not be reduced because of the lack of railway capacity. When they were placed in service in 1956 they proved to be masters of their work and the backlog was quickly cleared. An even bigger “Garrett” was proposed - Class “61” with a tractive effort of 115 000 lb and a 27 ton axle load but this was never to get any further than the drawing board, as Dieselisation was to be the new thinking (in the 1960’s) for motive power, as it was less labour intensive and oil was cheap, then!

Interestingly, in the 1990’s, the National Railways of Zimbabwe had refurbished some of their “Garratt” fleet, in order to reduce Zimbabwe’s dependency on imported diesel oil, as they had coal in abundance at their Wankie Colliery. However since the early 2000’s the railway has suffered along with the rest of the country’s economy under Robert Mugabe’s regime and there has been a general run down of railway operations. There are about ten “Garratt’s” still in steam, which are used mainly for shunting in the yard at Bulawayo, but on occasion one is brought out for a tourist “Rail Safari” to Victoria Falls.

In 1968 the last Beyer-Garratts to be newly built were eight 2’-0” narrow gauge (610 mm) S.A.R. Class NG G16 locomotives, which Beyer-Peacock sub-contracted out to the Hunslet Engine Co. of Leeds, who in turn used its South African subsidiary, Hunslet Taylor, to fulfil the work, with only the boilers being manufactured by the parent company.

Alas the Beyer Peacock Co. closed down their 112 year old (1854-1966) business having failed to make a profitable venture of making diesel locomotives.

The Beyer-Garratt was a very successful form of articulated steam locomotive and had it not been for Dieselisation and Electrification it could well have been developed still further. It enabled railways (especially those in Africa) that were laid with a narrower gauge and light rails to operate train loads as great as those in Europe on the 4’-8½” Standard Gauge.

We are fortunate that a GMA/GMAM has been saved from the breaker’s torch. She is No. 4079, named “Lindi Lou” and she is owned by the Sandstone Heritage Trust and can be seen in all her glory at the “Reef Steamers” Open Day (usually held on the last Saturday of July) at the historic Germiston Steam Locomotive Depot.

Class GMA/M 4-8-2 + 2-8-4 (Great South Africa Steam Train Festival)

References

- “Railways of Southern Africa” by O.S. Nock.

- “Railways in Transition from Steam 1940-1965” by O.S. Nock.

- “Steam Safari” by Colin Garratt.

- “Steam in Africa” by A.E. Durrant, C.P. Lewis & A.A. Jorgensen.

- “The Beyer-Garratt story” by H.M. Fleming in the Trains Illustrated Annual 1960.

- “Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways, Volume 2” by D.F. Holland.

- “The Garratt Locomotive” by A.E. Durrant, RAILWAYS Southern Africa, Dec. 1977.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.