Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

During the past few months a number of South African university campuses have seen a spate of student protests against the presence of statues honouring our colonial past. Rightly or wrongly, these have resulted in the vandalization and removal of some of these memorials.

Without entering into a debate on some of the more ludicrous, and sometimes racist arguments put forward by either side, this is a matter which has implications for our national heritage, and for the preservation of our historical environment, and is thus in need of serious consideration.

In 1811 Joseph de Maistre wrote that every people gets the government it deserves. By extension then, they also get the heritage they merit, and as building after building in our city centres continue to fall before the demolisher’s hammer, many white South Africans have been left wondering exactly what they have done to warrant the destruction of so many of their memories.

To many, 1994 marked a turning point in our history, when we had the opportunity of leaving the horrors of racism behind and embracing a bright new future, free of the guilt and remonstrations for past actions. But that is not the way of history, whose flow does not have sharp corners or U-turns, but moves inexorably through linear time. Instead of being blind to the lies and dark secrets of our colonial past, history has a habit of bringing these to the surface where, like suppurating sores, they are revealed for all to see. The process of healing is admittedly painful, but only exposure to the light of critical examination and the fresh air of open debate can bring closure, while censorship and ignorance are band-aids which may hide facts for a time, but ultimately only delay the inevitable.

To others a better marker of our racial history is set 46 years earlier, in 1948, when the Nationalist Party came to power. Most people who voted in that election are now dead or silenced by old age, and thus the blame for their criminal act can be safely transferred to their generation. This conveniently forgets that the colonial theft of land did not begin with Apartheid, but much earlier, in 1652, when the Khoi began to yield, under protest, to Dutch invaders. The assault upon the Xhosa nation began in 1781, and upon everyone else after 1836. The Dutch were in the forefront of such aggression but, for all their protestations, the English were never too far behind.

As a result between 1806 and 1906 at least 39 major battles and innumerable smaller skirmishes were fought between colonial armies and indigenous forces resisting the alienation of their ancestral lands. This averages at approximately one major confrontation every 31 months, and when we consider the effect that similar bloody events at Sharpeville in 1960, Soweto in 1976, and Marikana in 2012 have had upon our national psyche, then one begins to understand the impact that a history of repeated massacres must have had upon our ancestors only five or six generations removed. The German slaughter of 77,000 Herero men, women and children in 1904-7 in neighbouring Namibia must have resounded like a thunderclap throughout Southern Africa. Time wipes out the specifics of a bloodbath, but not the emotional trauma or the lingering knowledge of what took place.

There is evidence to show that many white South Africans knew that their actions were wrong, even by the standards of their time, and were contrary to the Christian beliefs they professed to hold. Fearing retribution, for the God of their Bible is a vengeful god, in 1948 they sought the protection of a political party, that promised them the security of an armed laager. By 1990 it had become obvious that their war was a lost cause, and so the election of 1994 became an act of atonement which may have reversed racist and discriminatory legislation but failed to wipe out 188 years of atrocities.

Whites were also at the delivery end of the stigma of racial discrimination, and the petty and constant humiliation that was inflicted upon men and women of colour on a daily basis. By European standards of the time many of these were educated, and well-equipped to voice the grievances of their people, yet for more than a century their patient and reasonable demands were derided and ignored. They belonged to a rising middle class educated at missionary technical schools such as St Mathews and Butterworth, and academic colleges such as Lovedale, Adams and Healdtown. Their leaders included men of stature such as John Jabavu, Sol Plaatje, John Bokwe and Tiyo Soga who, despite their age, intellect and gravitas were still referred to as “boy” by ignorant white buffoons, were expected to defer to a white child when walking on a pavement, and were forced to use the kitchen door when calling at the home of a white family.

Words, actions and material objects have symbolic meaning, and buildings have significance that extends beyond the scope of mere bricks and mortar. During the 1970s and 1980s the South African Government manipulated the work of the National Monuments Council to meet its own white supremacist political agenda, and its committees were controlled by members of the Afrikaner Broederbond. When, in 1987, the Post Office issued a set of definitive stamps bearing images of historical and civic architecture, it did so to celebrate the “establishment of the Western European civilization at the southern tip of Africa”.

An Old National Monuments Council Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

Given the significance that white South Africans obviously attached to their colonial buildings, it was not unnatural that black South Africans should perceive such architecture to be a symbol of their subjugation and humiliation at the hands of colonial “masters”.

In these terms, the antagonism shown by our students towards colonial symbols must be seen as a natural reaction against historical wrongs. Despite their inability to speak, the statues of tyrants still have the ability to remind us of times past, and bring back memories, both good and bad. And so do their buildings.

Strangely enough conservative Afrikaners, the very people for whom the Apartheid system was invented, hold a similar hatred for colonial buildings, and in 1990 some of them had no compunction in exploding a bomb in Melrose House, in Pretoria, simply because the Peace of Vereeniging was concluded there in 1902.

An inability to forego such atavistic hatreds and harness the historical built environment to more pragmatic uses does not bode well for its future. The vandalisation of unwanted statues is not the mere rejection of a hurtful colonial past, but is also a rejection of its material values and achievements.

I acknowledge the sentiment and the right of South African citizens to remove the symbols of racist humiliations and national hurt, but I do not understand where this road is going to lead us. Neither, I suspect, do the leaders of this movement.

Rhodes’ statue in Cape Town may be gone, but the Rhodes Memorial still stands within hailing distance, and his Trust Fund continues to hand out bursaries to students of all backgrounds. What is gone forever is our reputation as the nation that stepped back from a racial holocaust, and made an intelligent and measured transition from racist oppression to democracy. While these events have not brought the restoration and revalidation of old buildings to a halt, it is clear that the criteria that will need to be used in future in allocating public funds for similar projects will be expected to undergo a more stringent litmus test of political and social acceptability.

Rhodes Memorial (Wikipedia)

George V was a lousy father who spent his spare time sticking stamps into albums and gave the British nation a Nazi king. History is in agreement on those points, but his presence today also acts as a visible marker to events of the past. We need to tell our children about the evils of Apartheid, but cannot do so without visible reference points.

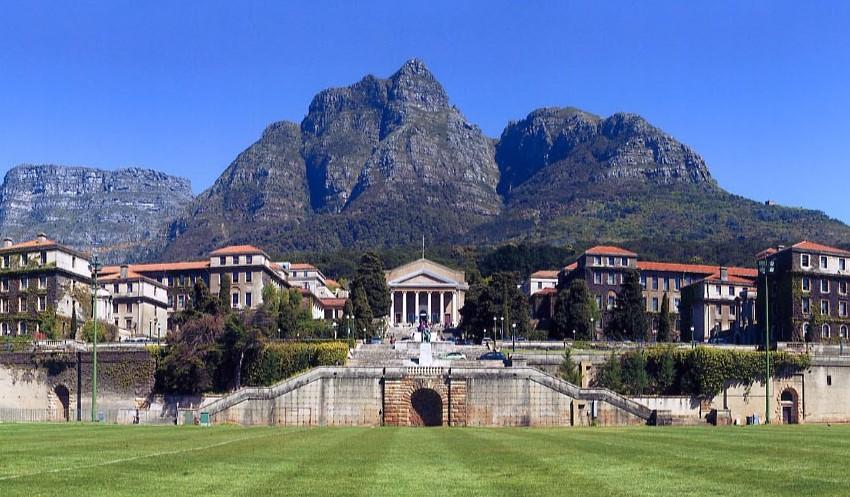

Other than a brief adrenalin rush, bringing down a statue will not change history, merely wipe out its memories. On the other hand, in the long term old buildings and artefacts are capable of meeting new needs and functions. Today our political leaders run our democracy from offices in the Union Buildings, while the Voortrekker Monument has been transformed into a venue where residents of Pretoria, regardless of race, colour or creed, can hold conferences, sip afternoon tea and hold picnics. And teenagers who want to see a creepy horror show can visit inside the building.

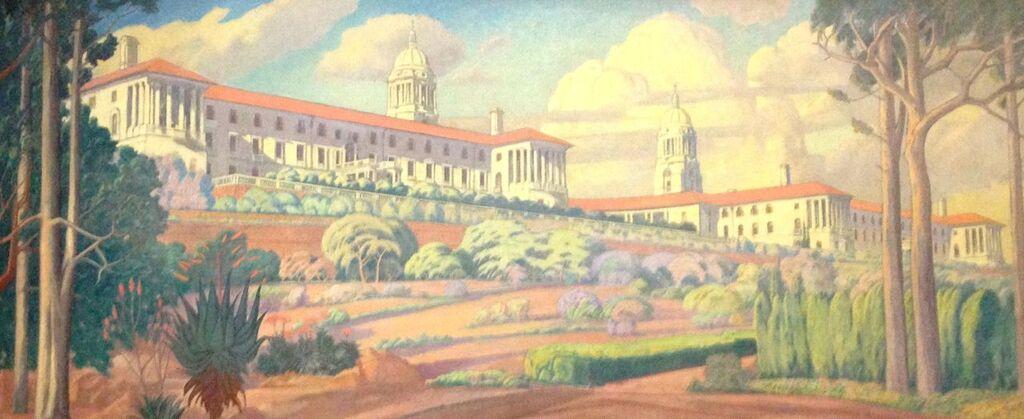

Pierneef Painting of the Union Buildings (photographed at an exhibition hosted by The Heritage Foundation)

Apartheid was a hateful institution, but many of its buildings have become symbols of greater things.

Having said that, I bristle at the fact that I am still forced to drive along John Vorster Rylaan in Pretoria, or visit the villages of Kaffirkuils Rivier and Three Cups in the Cape. For the benefit of those not in the know, a slave insurrection took place at Stellenbosch in 1724, and after its three leaders were captured, they were decapitated and their heads impaled on spikes at a crossroads nearby. Thereafter the Dutch called the place “Drie Koppen”, which the English, not knowing any better, subsequently translated to Three Cups.

And those, I think, are insults in dire need of vengeful retribution!

Postscript

The question of memory is key to the process of cultural conservation, which is why totalitarian-minded regimes will go to great, and often ridiculoue, lengths to rewrite history. Mr Malema and many present government ministers would have felt right at home in Mussolini’s Italy.

The propensity for Modernists to treat the user public as idiot lumpen is not limited to symbols of the past. In 2004 Umberto Eco pointed out that one of the consequences of being lumpen is that you are also expected to have a short memory span. Working on the basic assumption that “il Duce ha sempre ragione” (Mussolini is always right), in 1941 the Italians declared war on the United States and killed off Mickey Mouse, orTopolino (Little Mouse), as he was known locally. They replaced him, as if nothing had happened, with a character called Toffolino, who still had four fingers. His friends retained translations of their American names. The name Toffolino is a piece of untranslatable Italian gobble-de-gook.

Buffalo Bill underwent an even more absurd comic book transformation. Italian publishers initially reproduced the comic in its original American format, but although its front cover read “Buffalo Bill, the Hero of the Plains”, the inside text was changed to “Buffalo Bill, the Italian Hero of the Plains”. Then, in 1942, the Publishers inserted a notice, in large typeface, explaining that it had since been discovered that William Cody’s real name was Domenico Tombini, who came from Romagna. By some amazing coincidence, Mussolini also came from Romagna. Presumably their readers were expected to be too stupid to remember such changes in identity (Umberto Eco. 2004. The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana). By the time I had started reading Italian comics in 1950, their original names had been reinstated and people could laugh at (and remember!) the idiocy of such attempts at social engineering. .

A satirical view of Modernist thought and politically correct values was made in the 1970s in a science fiction story whose name and author, regrettably, I have not been able to trace. The plot postulated a Leninist-Stalinist future not too different from our present where true equality was achieved by handicapping the talented to a common level with the lumpen. In this society graceful ballet dancers had to perform with lead weights attached to their arms and legs to make them clumsy and less intimidating to average persons, good looks had to be hidden behind grotesque masks, and creative thinkers were forced to wear ear-pieces which received a mind-splitting shriek broadcast every 30 seconds to interrupt their thought patterns. In that way everyone was rendered equal and no-one could remember how things had once been. Significantly, the enforcers of the system were not impeded by any such devices.

Franco Frescura - Professor and Honorary Research Associate, University of KwaZulu-Natal. He is currently engaged in the documentation of the historical built environment of Durban, including aspects of its oral history and material culture.

Main image courtesy Don Shaw

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.