Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

A large sepia-toned photographic portrait hangs in an entrance hall, the dignified sitter gazing out. The placement of the portrait is central, deliberate. Encased in a slightly worn yet delicately carved wooden frame, an elderly lady, elegantly dressed, stares confidently into the camera. Her posture is straight, with a brooch visible, pinned to her dress. The wooden frame, dating from more than a hundred years ago, has a small crack, with the protective glass showing dust and small scratches, but her gaze remains clear - fixed, unwavering, as though watching over the entrance hall.

In this regularly frequented room, the portrait photograph has become more than an image - it has a distinct presence – a presence not to be ignored.

Today, she is someone’s ancestor. A person of significance, or just an ordinary South African citizen of the time.

The evolution of photographic portraiture contributed to the rich and diverse field of photography we know today. These early photographic portraits, from between the 1880s and 1920s, stand as evidence of human ingenuity and our desire to capture and preserve personal and historical moments. They have become a powerful tool in shaping cultural narratives in that they are closely tied to social status and identity.

Framed, wall-mounted portraits were not merely decorative. They became central to domestic life and symbolic of personal, familial, and sometimes political narratives. They also played a vital role in historical documentation, capturing images of ordinary people, significant figures, men and women in uniform, sporting events, and other key events of the time.

Photographic portrait or painted portrait? The predecessor to photographic portraits were painted portraits. As with many portraits, it is unclear whether it is actually a photograph or an outstanding piece of art work. This portrait of the couple Anna Catharina Lindeque and Johannes Jacobus Scheepers is beautifully framed with their names added, which in itself is unusual. The provenance around this rather modern looking framed portrait is unclear. The frame and images are in pristine condition given their age. The couple got married early 1800s, prior to the invention of photography, but they may have had photographs taken of them in their advanced stage of life (post 1850), which were then hand coloured.

Unknown couple in elaborate golden coloured frame with convex glass (circa late 1890s)

Portrait photographs themselves were either of an individual sitter, couples, a family, work, sport, or military groups. Poses and expressions of the sitters in their period attire, uniform, or traditional dress were mostly formal. These portraits usually formed part of a collected family memory or functioned as a historical artifact.

As an intimate and potentially political object, the wall portrait transformed the home into a site of memory, belonging, and identity-making. The images reveal stories of family, nationhood, and the human need to be seen, remembered, and loved.

Each photographic portrait contains visual details, emotional resonance, and historical context. This makes them valuable from a heritage point of view. Photographic portraits are indicators of respectability and lineage. Often, they are grouped in family galleries, showing multiple generations in formal attire, occasionally accompanied by memorabilia such as military medals or certificates.

Unfortunately, wall-mounted photographs have become neglected photographic artifacts, mainly because we can no longer relate to the sitters, or we are not inclined to preserve the family heritage.

This article briefly reflects on these wall-mounted photographic portraits between the 1880s and 1920s.

Exceptionally large, elaborate and heavy-framed photograph of 14-year-old Molly Hendricks (circa 1910). What was her life story?

An unknown couple in elementary wooden portrait frames. Depth is created with the mounting of the photographs in double layers of picture frame mats in different colours (circa 1895)

Spouses - Cornelius Gysbert Johannes van Niekerk, born 5 January 1840, and Susanna Elisabeth van Niekerk (Gous), born 22 December 1843. The couple had 4 children (2 daughters and two sons). It is not often that the sitters names are recorded on portrait photographs, which makes this photographic portrait unique. The enlarged photograph is mounted in a simple carved wooden frame of the era (circa 1900).

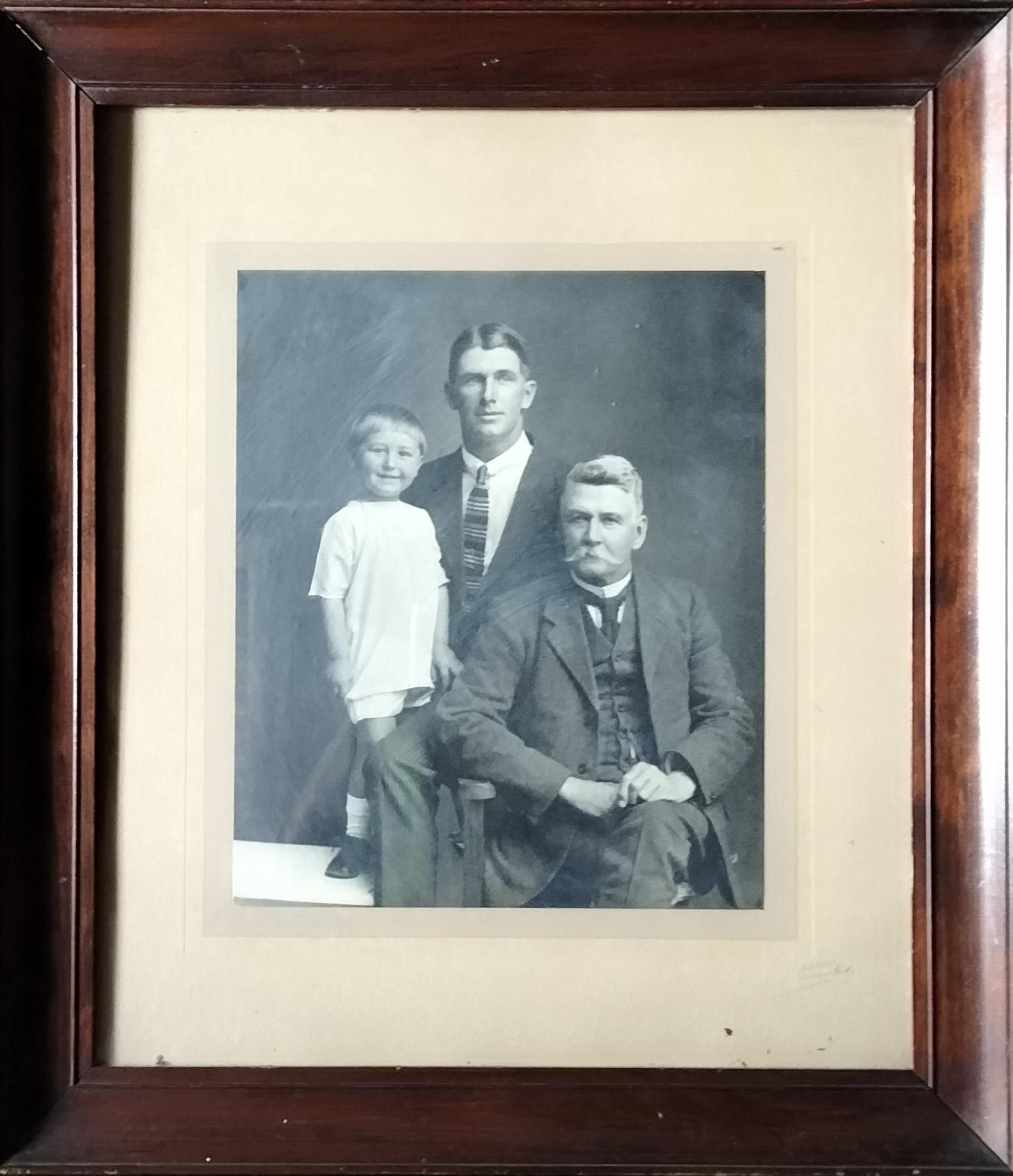

Unknown trio - Three generations by a Kroonstad-based photographer (circa 1920s). The photograph is neatly mounted in an upmarket wooden frame

Hand-coloured enlargement of an unknown couple mounted in a broad wooden frame (circa 1920s)

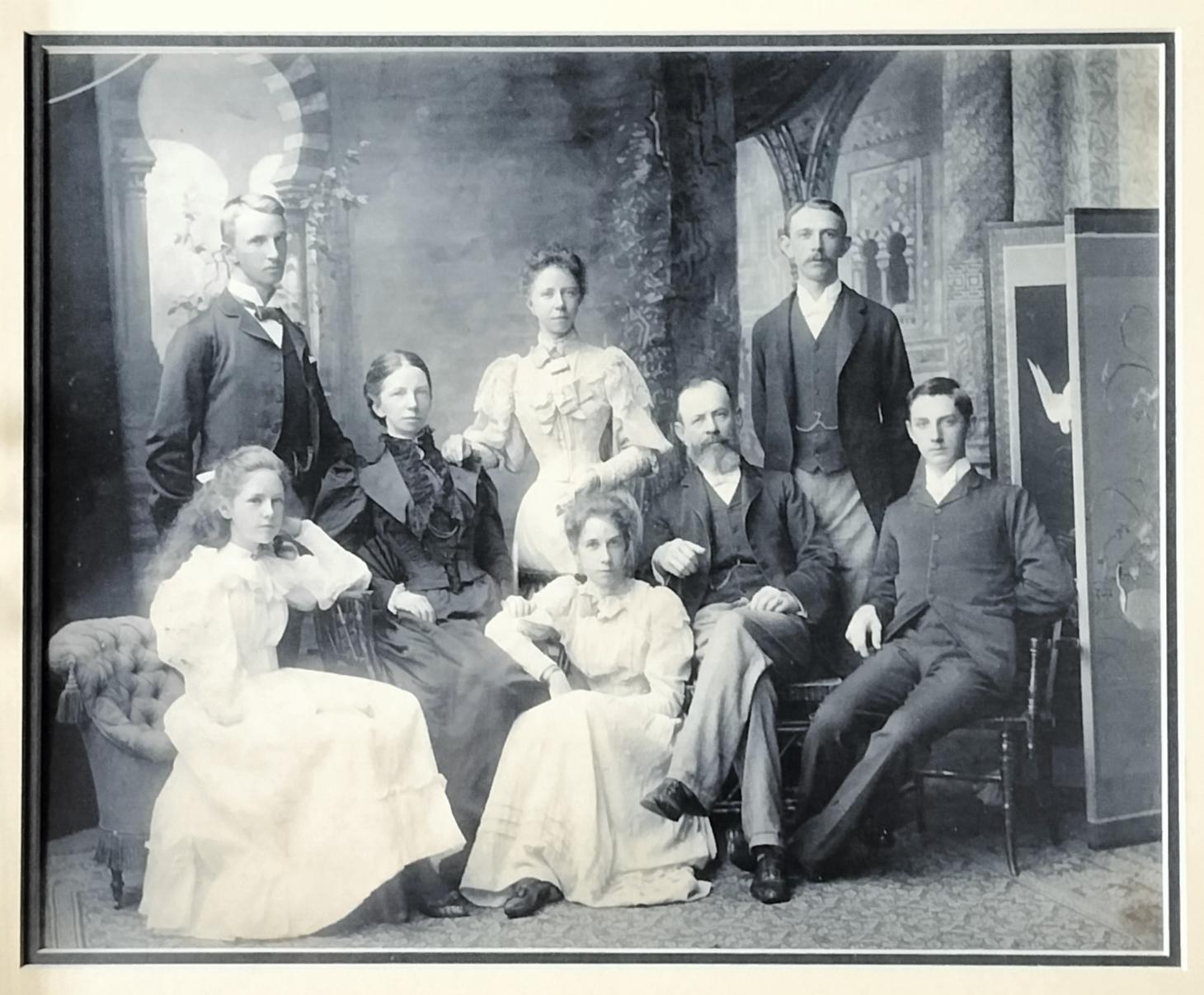

An unknown well-to-do family of eight. To save the beautiful, enlarged photograph, the photograph has recently been reframed.

Unknown wedding couple. The elaborate wooden frame also shows a golden coloured inner liner. This portrait is an example of how images of this nature deteriorate over time due to insect infestation. Fish moth damage can be seen on the left of the photograph (circa 1905).

A) Reflection on the history of wall-mounted photographic portraits

A life-size framed photograph has its origin in a smaller negative. Each photographic portrait is therefore an enlargement from the original image, typically captured in a photographic studio.

By the 1860s, with the advent of albumen prints and studio photography, larger photographic prints became possible. Colonial elites - European settlers, military officers, and merchants - began commissioning studio portraits to be mounted in ornate wooden or gilt frames and displayed prominently in their homes. These portraits functioned as visual affirmations of class, mirroring the oil paintings originally found in early South African drawing rooms. Photographic wall portraits thus emerged not only as personal heirlooms but as tools for constructing and reinforcing identity in the domestic sphere.

Although photographs were enlarged and framed as early as the 1860s, photographic processes and printing technologies advanced the growth in production of these formats of photographs between the 1880s and the 1920s. From the 1920s, the uptake of this type of format became widespread worldwide.

The resultant framed photographs were sometimes hand-coloured or retouched with charcoal, crayon, or watercolour to give them a painterly effect.

A snapshot showing James E. Kent in his house in Melville, Johannesburg. The framed family portrait on the wall and the sheet music on the left are notable features of this early 1900s household.

Contemporary photograph of three generations of praise singers: Kearabetswe Pitsoe with his grandmother, Mmantshope Pitsoe holding an image of her grandmother. This photograph confirms the importance of carrying over traditional values and skills from one generation to the next. The fact that the Nkhono/Gogo and her grandson could include the image of an earlier generation enriches the heritage value of the photograph. It is also enriching to see how a young man embraces his rich cultural heritage.

A unique large format photograph of an unknown family of 10 mourning the loss of a wife, mother and grandmother. To ensure inclusion of the departed matriarch in the family photograph, her husband holds up an oval framed photographic portrait of her – a photograph that would have been captured before her death.

B) South African Framed Photographic Portraits

In a South African context, framed photographic portraiture is deeply intertwined with the country’s colonial past, the advent of photography in the 19th century, and the complex social and racial dynamics of the time.

From its colonial beginnings as a symbol of European power and taste to its later role in African self-fashioning, the wall-mounted photographic portrait in South Africa offers a rich visual history of our nation.

The photographic portraits are typically hung in entrance halls, drawing rooms, living rooms, dining rooms, above a fireplace, or even in bedrooms.

Many South African homesteads still contain these early framed portraits. Whether commemorating a wedding, mourning a loved one, or honouring a political icon, these images turn walls into personal museums of family, faith, and struggle.

Sadly, many South African photographic portraits have little provenance in that they do not contain the name of the photographer or the sitter. Where the names of the sitters have been recorded by family members (typically written on the back of the portrait frame), this assists genealogists.

Although photographic portraits of the South African Black community are less common compared to the white population, a class of mainly mission-educated Black South Africans also started adopting the practice of displaying framed portraits by the late 19th and early 20th century. These portraits signalled respectability and Christian identity (echoing missionary ideals), aspiration, and social mobility, often showing the subject in Western-style dress, connected to global modernity, emphasising literacy and education.

Some of the photographic work produced by the South African photographers David Goldblatt and Roger Ballen highlights the aspect of class. Both photographers portrayed images of rural white South Africans in their natural milieu, often with a portrait mounted on the wall in the background. These photographs have, unintentionally, created a stereotype around wall-mounted photographic portraits being associated with the poorer South African community.

To commission a formal studio portrait—and frame it for wall display—implied a certain level of economic stability and access to urban photographic services. Although framed photographic portraits were mainly requested by sitters of the middle and upper class, the images by Goldblatt and Ballen confirm that, irrespective of class, maintaining a memory around family, by hanging framed photographic portraits, remains part of our human inclination.

Photographs by renowned professional South African photographers such as Goldblatt capture the social and emotional importance of retaining family memories. This David Goldblatt photograph has the following description: “A pensioner with his wife and a portrait of her first husband. During the Great Depression he found work on the S.A. railways. For the past 19 years he had lived with his wife and daughter on this plot at Wheatlands, outside Randfontein. The plot had a windmill, a few peach trees and a patch of mealies. Transvaal (Gauteng), September 1962.” – Image provided by David Goldblatt Legacy Trust / Goodman Gallery.

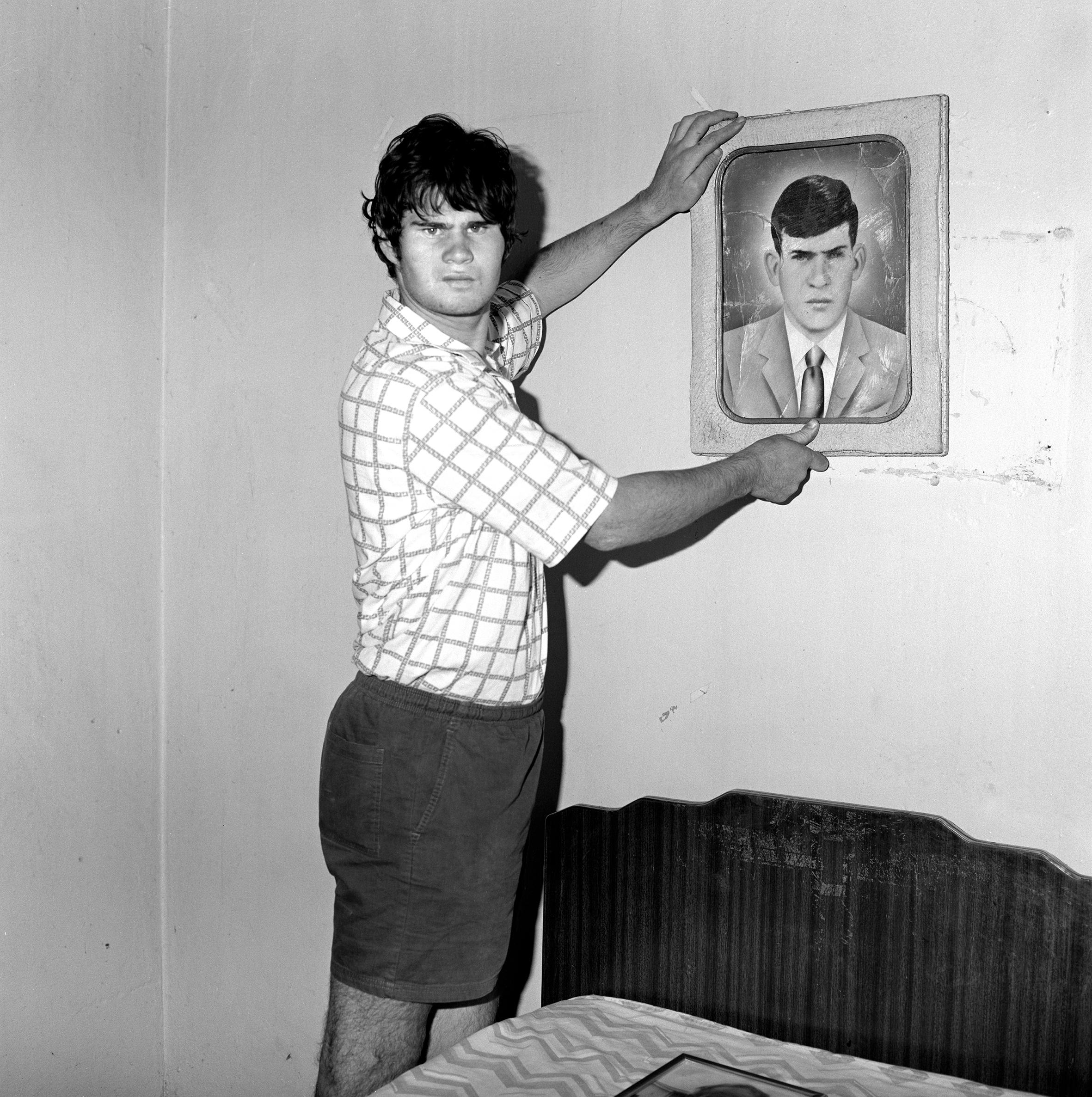

A Roger Ballen photograph with caption: "Factory Worker Holding Portrait of Grandfather, 1996." Image provided by Roger Ballen. Considering that the photographic portrait hangs in a bedroom, this young man’s grandfather must have had a significant impact on him.

C) Wall-mounted Photographic Portrait Frame Types

The early 20th century was a transformative period for portrait photography. It saw the evolution of technology, aesthetics, and cultural significance as photography transitioned from a niche art form to a widely accessible medium.

As photographic prints (albumen, salt prints, and the like) became more common, they were often displayed in decorative wall frames. To optimally display the photograph, the frame serves to protect and elevate the enlarged photograph within.

Antique photographic frames come in a wide variety of types and styles, often reflecting the materials, artistic trends, and technological advances of the 19th and early 20th centuries. These portrait frames in themselves have become of interest. These frames were as much a part of the photographic object as the image itself.

The resultant enlarged photographs were initially mounted in a deep wooden frame, with different varieties of frame types following thereafter, each as elaborate as the next.

Photographic frames varied vastly and typically contained:

- Gilt Frames - Made of wood with gold leaf or imitation gold finishes. Often ornate, with floral, scroll, or shell motifs.

- Walnut & Mahogany Frames - Popular in the Victorian era for their dark, rich tones and carved details.

- Shadow Boxes - Deep-set frames with glass fronts, used for portraits and sometimes for photos with added embellishments (hair, jewellery).

- Pressed Tin/Metal Frames - Often in gold with added aspects on the rims, such as leaves.

- Often included decorative mats or ovals to focus the viewer's attention.

Common features of antique photographic frames may include convex glass, various photographic mounting styles, and embellishments (including gilded scrolls, painted glass, velvet mats, or nameplates).

Opening the frames often provides for surprises. When restoring the photographic frames, one may stumble upon a second hidden image, find that the supporting backing is an old advertisement on hardboard, or more importantly, find the provenance written on the back of the photograph.

Vryheid Rugby Club – 1st team: Winners of the Mitchell-Innes, Meyer and Christopher trophies in 1930. The sitters are: Back row from left to right: PJM Smith, Joh Craig, SW van Heerden, WJ Wessels, JC Roos, RG Moffet, L Boyd, JM Claassens & D. Dekker. Middle row from left to right: PJ Swart, EJ McKechnie, RE MacKridge (President), FE de Jager (Captain), PJG vd Westhuysen (Secretary), CE Kruger and BA Caney. Front row from left to right: J Bell, GM Hattingh, JM Beukes and SS Cloete. Group photographic portraits such as these are useful to genealogists, sports and town historians.

Seven females – three generations. An unknown mother with her daughter and five grandchildren. Large group photographs in these standard oval frames with convex glass are not often seen. The photograph has been hand-coloured.

An unknown mother and her two sons. This hand-coloured photograph is mounted in a simple flat glass frame (circa 1920). Framed photographs of South Africa’s black population from this era are rare due to the Eurocentric nature and higher cost of portrait photography at the time.

Photograph of an unknown, elegant young lady mounted in a large wooden frame (circa 1920)

Large wooden framed portrait of Anglo-Boer War soldier. As per the inscription on top of the photograph, the soldier seems to be EB Eales, who was attached to the GFC Scouts (referred to as Geoghegan's Scouts), a British Intelligence Unit raised for service with General Settle's column. This unit was authorised on June 4, 1901, and disbanded on February 19, 1902. Eales is recorded to have been killed in action on 5 December 1901 at Spitzkop. The key question is, why would a large portrait of a British soldier have been produced in South Africa? Or was he possibly a South African who deserted to join the British forces?

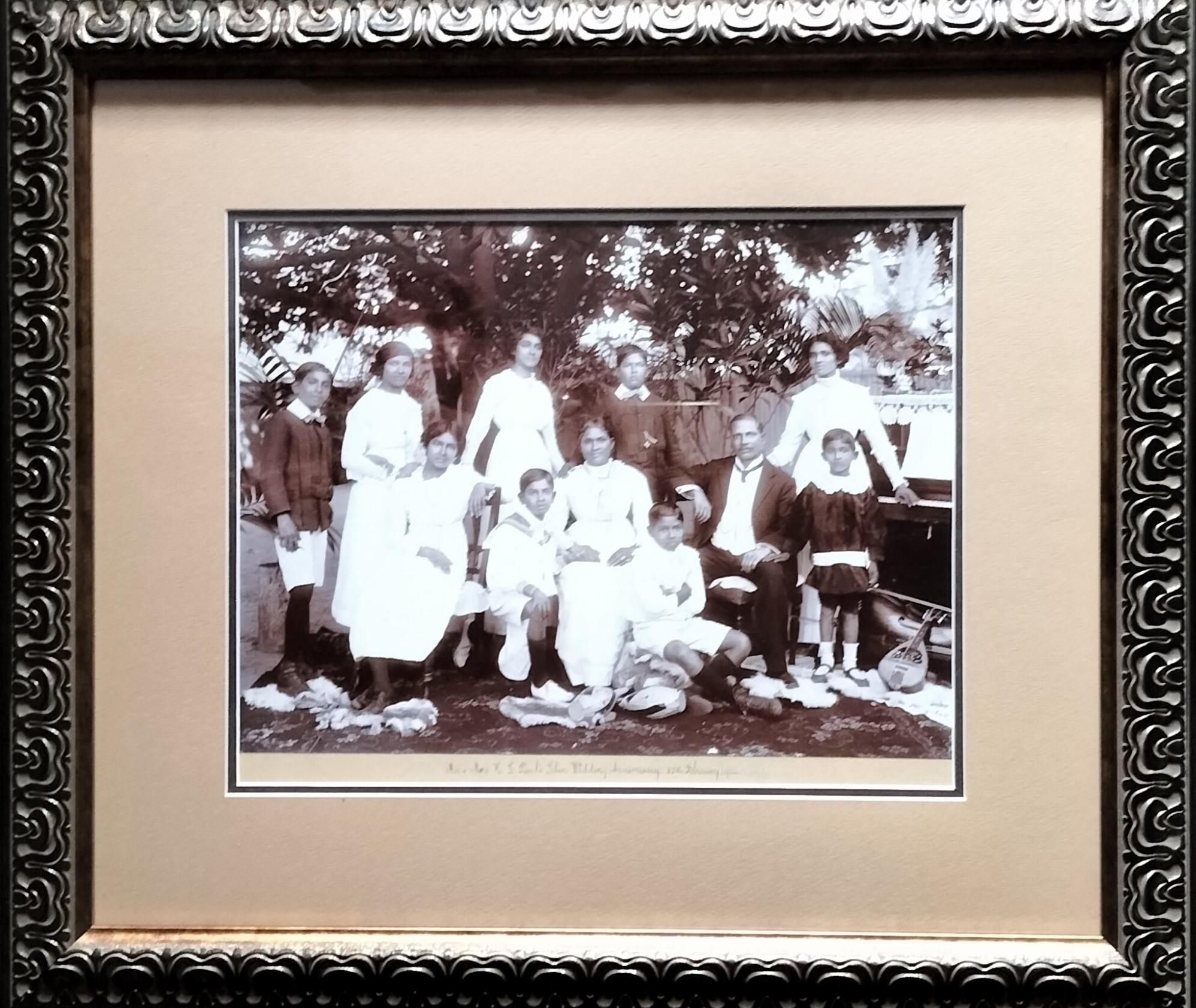

A large format framed photograph of Mr. and Mrs. HL Paul’s Silver Wedding Anniversary, 25 February 1914. Indian born Henry Louis Paul married South African-born Ellen Elizabeth Johnson in 1889. He was 25 and she was 16 at the time. Henry was a senior interpreter at the Department of Justice. Henry also played a role in establishing the Natal Indian Congress in the mid-1890s. In the photograph, they seem to be posing with their daughters and possibly some grandchildren. Note the piano and mandolin on the right.

Closing

Given that the portrait photographs under description are all more than one hundred years old, the condition of surviving portraits is not always the best. Either the photograph has foxing, or the portraits were exposed to light, severely damaging the original image. Water damage to these portraits is also common. Where the back covers (usually taped onto the back) start disintegrating, this allows for insects to enter the frames, causing damage to the image and wooden frames. Where the glass has cracked, the glass often scratches the photograph. Irrespective, cracks, fading, and patina of photographic frames are common and often provide historical character to these images.

In the 1920s and 1930s, capturing portraits shifted away from traditional studio poses to capturing sitters in their natural environments. These candid portraits reflected the subject’s personality, occupation, or social circumstances, giving rise to environmental portraiture.

When walking into a room where these photographic portraits are hanging, the question is, what feeling does it evoke for the viewer (whether a visitor or a family member)? Is it one of reverence, nostalgia, pride, loss, or even indifference?

Framed photographic portraits do not appeal to everyone. On occasion, visitors to my privately curated museum have commented that they find the images creepy and that they feel uncomfortable being in a space where all these old people stare at them – Odd.

On the other hand, these portraits are fortunately being picked up by individuals who appreciate the aesthetics and the heritage aspect thereof. A respectable number of these portraits end up in guest houses.

A subsection of the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC) contains a sizeable number of these portraits in what is referred to as the “Portrait Graveyard.” Curating these photographs is a challenge in that they assume considerable space and need storing in optimal conditions away from harsh temperatures, insect infestation, and in doing so preventing frame and glass damage. These portraits are mostly obtained from local charity stores, antique markets and car boot sales.

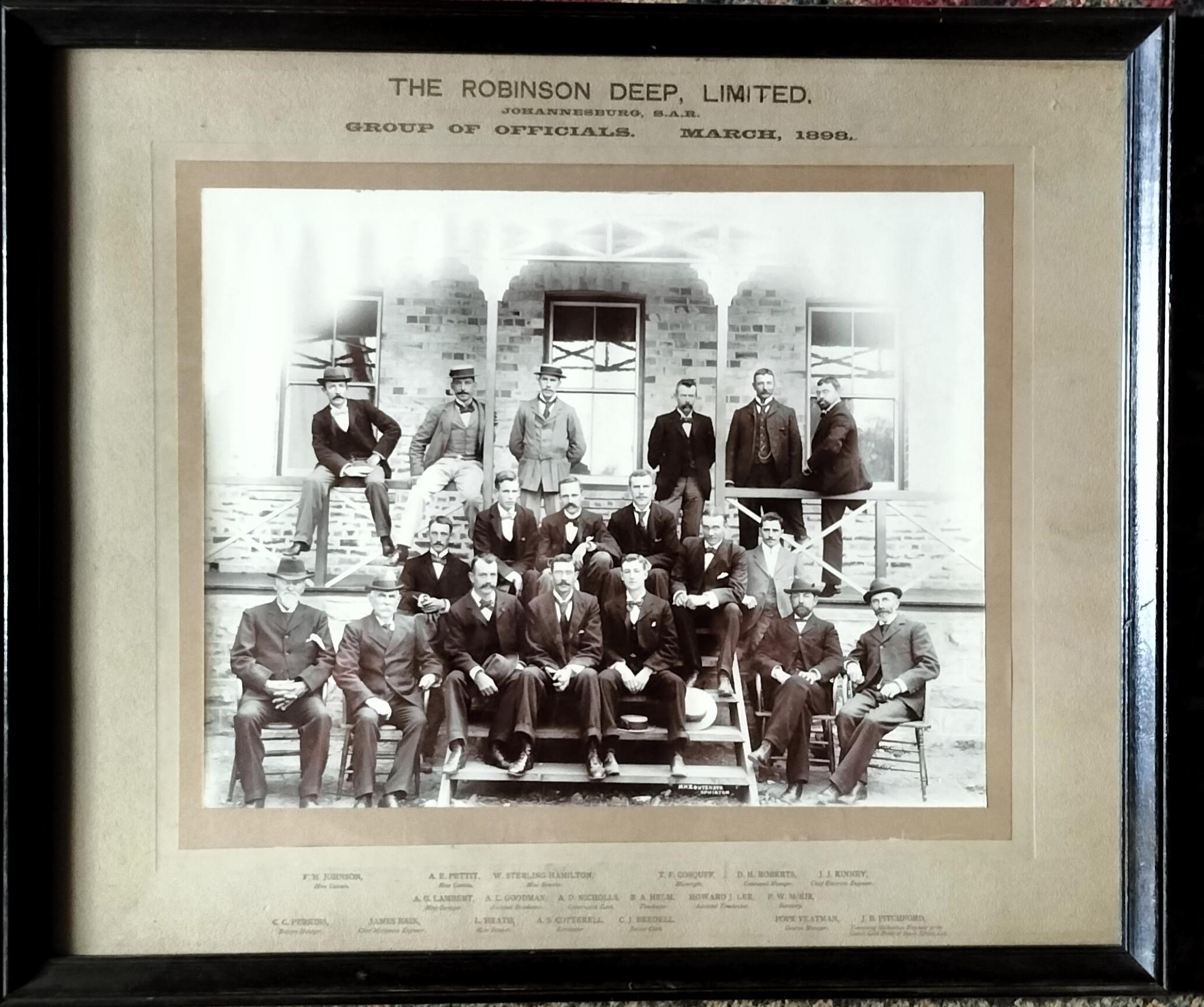

Large format framed photograph of Robinson Deep Limited mining employees taken in March 1898 by the Johannesburg-based (Ophirton) photographer NH Zoutendyk. This image would proudly have hung in the house of one of the individuals in the photograph. The sitters are, front left to right: C.C. Perkins (Battery Manager); James Bain (Chief Mechanical Engineer), L. Heath (Mine sampler); AS Cotterell (Storekeeper); CJ Bredell (Junior Clerk); Pope Yeatman (General Manager) and JB Pitchford (Consulting Mechanical Engineer of the Gold fields of South Africa Ltd). In the middle from left to right: AG Lambert (Mine supervisor); AL Goodman (Assistant Storekeeper); AD Nicholls (Construction Clerk); BA Helm (Timekeeper); Howard J Lee (Assistant Timekeeper), and PW McKie (Secretary). Back row from left to right: FH Johnson (Mine Captain); AE Petit (Mine Captain); W Sterling-Hamilton (Mine sampler); TF Cosguff (?); DH Roberts (Compound Manager) and JJ Kinney (Chief Electrical Engineer).

Photograph of an elegantly dressed lady mounted in a broad wooden frame with a golden inner liner (circa 1920). The line on the left of her face is a light reflection when the photograph was captured for inclusion in the article.

Large photographic portrait of an unknown baby by the Duffus Brothers (John & William). Their main studio was in Johannesburg, but they were also briefly based in Cape Town, where this photograph was captured. The frame has a silver inner liner (circa 1903)

Large photographic portrait of an unknown lady. What makes this image unusual is the silver-coloured fern leaf (which has probably shifted since the image was mounted). The frame is an original hand-carved wooden frame with a thin inner liner (circa 1908).

Large portrait photograph of an unknown lady by Port Elizabeth-based Hallis & Co (1893). Note the double-layer framing mats used in mounting the photograph, as well as the liner (thin metal strip set inside the frame). This portrait image is, in all probability, a modern reframe. As for many of these photographs, the image has been touched up with a pencil once enlarged, as seen on her dress.

Hand-coloured photograph of an unknown boy mounted in a metal portrait frame with convex glass (circa 1920). Note the added metal leaves on the edge of the frame.

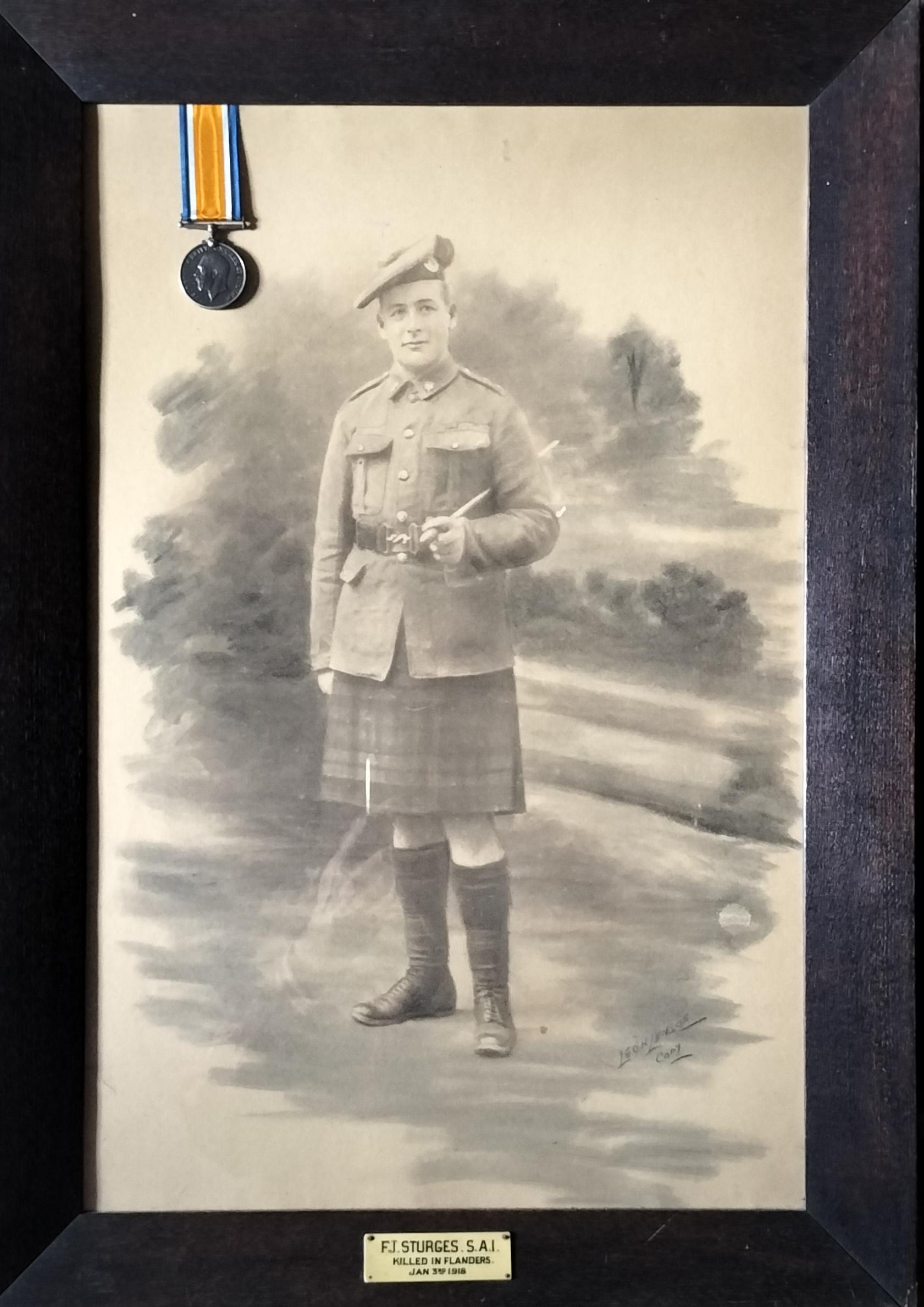

Framed photograph of FJ Sturges, attached to the 4th South African Infantry during the 1st World War. Francis Joseph Sturges was born in England in 1877. When he married Julian Nolan in Johannesburg in 1908, he resided at Val Station (near Standerton). The couple had three children at the time of his death. The framed photograph provides much provenance in that it includes an awarded medal and a little plaque confirming that Sturges was killed in Flanders on 3 January 1918 (aged 40). He is buried at Fins Sorel-Le-Grand. Framed photographs such as these, inclusive of medals, are fairly uncommon and have therefore become highly collectible. The background to this image has been artistically added.

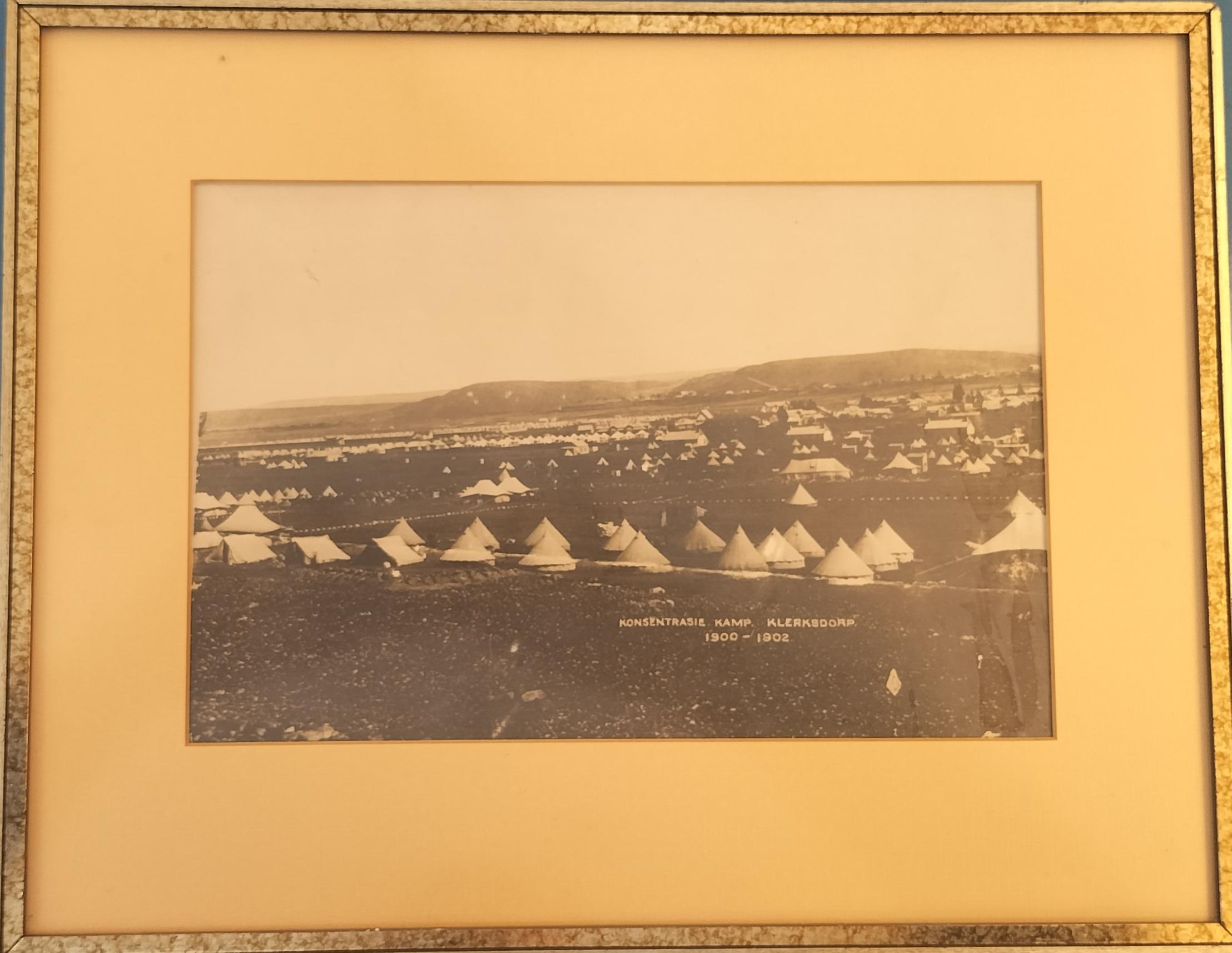

Photographic portraits were not only of people. They were also of places such as this photograph of the Klerksdorp Concentration Camp during the Second Anglo-Boer War. This photograph was probably enlarged and framed by a family member to memorialise a loved one who may have been incarcerated or even died in the camp. This camp has been described as somewhat of a contradictory camp. It seems to have been well run, but, despite this, there was a good deal of disease and a mortality rate which was considerably higher than the average concentration camp rate at the time.

Note: In photographing the photographic portraits for this article, every effort has been made to avoid light reflection. Due to the glass in the frames, many convex, this effort was not entirely successful, resulting in some of the images containing minor light reflection.

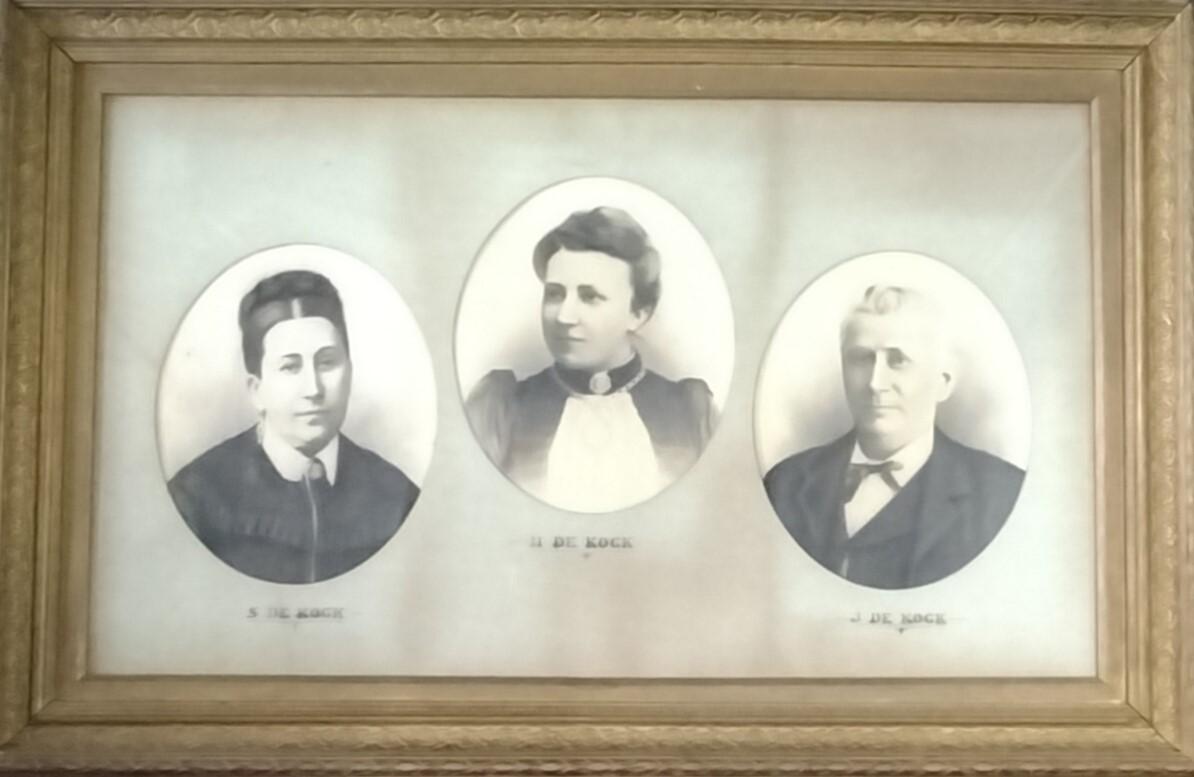

Main image: Very large combination photographic portrait of three De Kock family members – assumed to be parents with their daughter in the centre. The exact De Kock lineage still needs to be confirmed.

Special Acknowledgement

- David Goldblatt Legacy Trust / Goodman Gallery for sourcing and providing permission for the use of a David Goldblatt photograph

- Roger Ballen for sourcing and providing permission for the use of one of his photographs

- André Croucamp / Totem Media for sourcing and providing permission for the use a photograph from The Bafokeng Story

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Ballen, R. (2001). Outland. Phaidon. New York

- Ballen, R. (2011). Dorps. Protea Boekhuis. Pretoria

- Goldblatt, D. (2007). Some Afrikaners revisited – With essays by Antjie Krog & Ivor Powell. Tien Wah Press. Singapore

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC) – All images included in this article, except the Ballen and Goldblatt photographs and the photograph extracted from The Bafokeng Story, originate from the HPRC.

- Totem Media (2010). Mining the future – The Bafokeng story. Researched, written and edited by Totem Media for the Research & Planning Department of the Royal Bafokeng Administration. Jacana Media. Johannesburg

- Websites

- Angloboerwar.com (EB Eales)

- Familysearch.org (HL Pauls)

- Geni.com (Cornelius Gysbert Johannes van Niekerk)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.