This substantial volume by John Stewart is the first full-length biography of Sir Herbert Baker, written with empathy, sustained interest, and impressive scholarly depth. It is a long-awaited study and immediately establishes itself as a benchmark work on Baker’s life and career. Stewart approaches his subject with understanding rather than apology, and the result is a biography of breadth, seriousness and quiet authority.

Book Cover

The book spans Baker’s entire life: his English upbringing and professional formation; his decisive South African years; his Indian interlude at New Delhi; and his later work in Britain and on the European battlefields of the First World War. It also makes clear—without labouring the point—that Baker has been celebrated, studied, and defended more fully in South Africa than in the United Kingdom. Stewart does not attempt to correct this imbalance polemically, but the contrast hovers in the background throughout the book.

The publication history of the biography is itself telling. The first edition, published in 2022, carried the subtitle 'Architect of Empire'. The South African edition issued by Jonathan Ball in 2025 adopts the more neutral 'A Biography'. Yet there is no escaping the judgement that Baker was a committed adherent of the British imperial project. He was closely associated with Alfred Milner and the so-called Milner’s Kindergarten, and his career trajectory in southern Africa was inseparable from the ambitions of British administration and power.

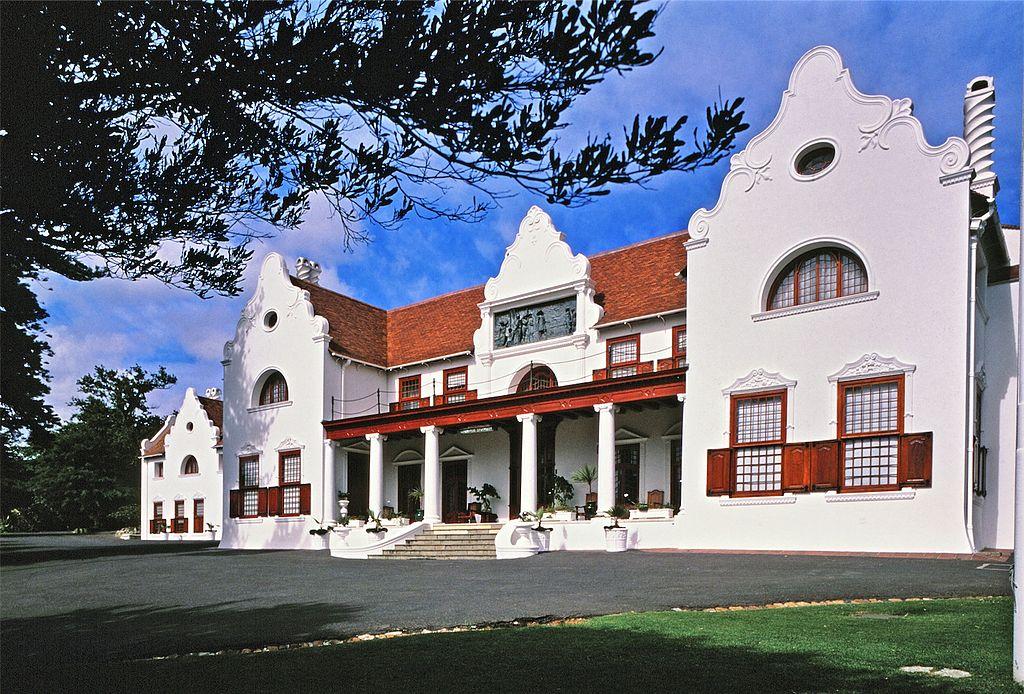

Baker’s appointment as Cecil Rhodes’s architect proved decisive. Stewart charts in detail Baker’s work at Groote Schuur, redesigned not once but twice following the disastrous fire, and shows how this commission established Baker as the architectural interpreter of Rhodes’s imperial vision.

Groote Schuur (Wikipedia)

From Cape Town, Baker built a flourishing practice, before relocating to the Transvaal after the South African War to position himself astutely for the major public commissions of the new British administration: Pretoria Railway Station, Government House, and St Alban's, the Anglican Cathedral in Pretoria.

Old photograph of the Pretoria Railway Station (SA Builder Magazine)

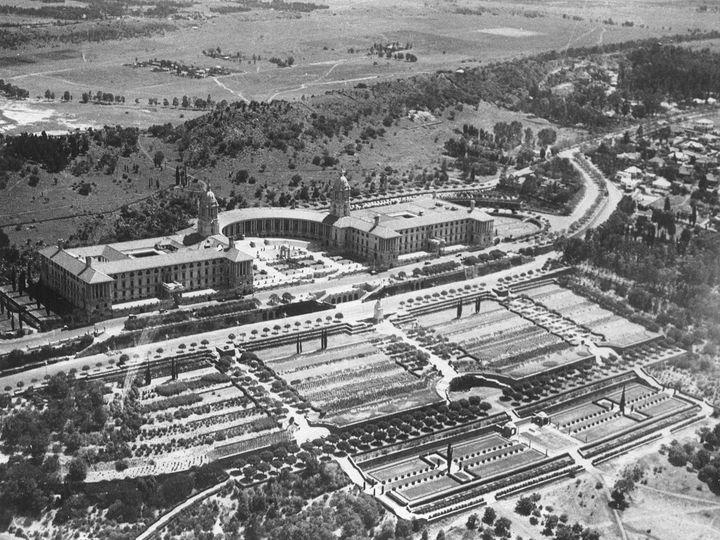

The architectural pinnacle of Baker’s South African career remains the Union Buildings. Stewart treats this great work with appropriate seriousness, situating it within its political and symbolic context while allowing its architectural achievement to stand independently. The building’s siting, axial planning, classical language, and use of local materials are all carefully unpacked, and the Union Buildings emerge once again as one of the most powerful civic statements made in South Africa in the early twentieth century.

Old photograph of the Union Buildings from the air

One of the most revealing aspects of the biography—and one that resonates strongly when read alongside Baker’s South African memorials and his later European war work—concerns the formative educational journey funded by Rhodes. Rhodes not only employed Baker but sent him, at his own expense, on an extended and deliberate architectural pilgrimage to the great classical sites of Italy, Sicily, Greece, and the wider Mediterranean world. In effect, Baker became the first beneficiary of Rhodes’s educational largesse: a kind of proto-Rhodes Scholar, absorbing at first hand the architecture of antiquity—temples, theatres, commemorative landscapes, and the language of classical monumentality.

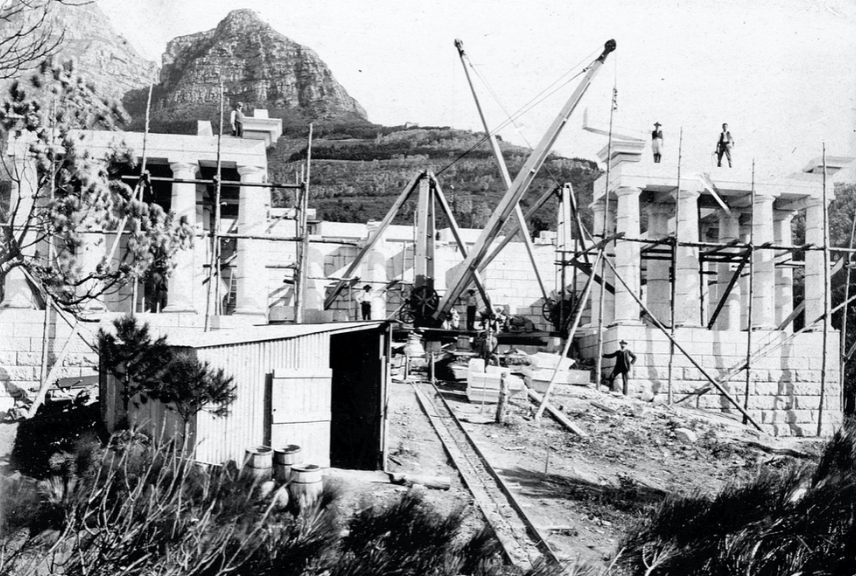

While Stewart records this journey, it is through close reading of the biography, combined with sustained study of Baker’s South African work and his memorial architecture on the European battlefields, that one sees its full significance. Classical architectural idiom—proportion, procession, axiality, and symbolic restraint—became a lasting departure point for Baker’s memorial language. This can be traced from the Rhodes Memorial above the University of Cape Town, to the Memorial to the Honoured Dead in Kimberley—now a somewhat isolated and poignant relic of the South African War—and to the Alan Wilson Memorial to the Shangani Patrol situated on the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe. In these works, Baker fused classical allusion with narratives of sacrifice, tragedy, and heroic loss.

Rhodes Memorial under construction (Cape Town Photographic Society)

This synthesis reached its most mature and restrained expression in Baker’s later work for the Imperial War Graves Commission in France and Belgium. Baker along with Lutyens and Sir Reginald Blomfield were the three chief War cemeteries and memorials architects. There, amid the devastation of industrial warfare, Baker employed a disciplined classical vocabulary to commemorate mass death with dignity and emotional control. Read in this light, there is an indirect but undeniable debt owed to Rhodes—not merely for patronage, but for his belief in education and travel as formative forces. Baker himself internalised this lesson and later established a travelling scholarship, ensuring that younger architects might experience architecture directly. In doing so, he helped nurture what might reasonably be described as a Bakerian school in South Africa: grounded in craftsmanship, classical discipline, and moral seriousness.

Baker’s departure from South Africa to collaborate with Edwin Lutyens on the new imperial capital at New Delhi marks a turning point in both his career and reputation. Stewart gives a compelling and balanced account of the Baker–Lutyens quarrel over gradients, sightlines, and the placement of buildings on Raisina Hill. The dispute was a sad one, and it diminished both men. However, its consequences fell more heavily on Baker. Lutyens, with superior social and professional networks, proved adept at shaping the narrative, and his dismissive judgements of Baker’s architecture entered the historical record with disproportionate force.

North Block Secretariat New Delhi (Wikipedia)

Stewart does not deny Lutyens’s brilliance—nor should he—but he does expose a capacity for malice and small-spiritedness that complicates the heroic image often attached to Lutyens. Why for example was Robert Byron, (one of my favourite pre-war travel writers on Persia) the man who wrote the critical and rather denigratory review of Baker’s architecture for Country Life and the Architectural Review? I cannot help but conclude that Baker was, in many respects, unfortunate to stand in the shadow of a figure who dominated British architectural memory so thoroughly, but also unlucky in his conflict with Lutyens. Baker deserves to be judged on his own terms, not merely as a lesser foil to Lutyens. There are only two Lutyens works in South Africa... the Rand Regiments Memorial in Saxonwold (now renamed the South African War Memorial) and the problematic Johannesburg Art Gallery in Joubert Park, but these need another discussion.

Rand Regiments Memorial (Lutyens Trust)

Old photo of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (Lutyens Trust)

One of the biography’s great strengths lies in Stewart’s use of the Baker archives, particularly the intimate correspondence between Herbert and his wife Florence. These letters lend warmth, humanity, and emotional depth to a life often assessed solely through professional commissions. Baker was a good father and a true and respectful husband. Stewart also succeeds in conveying the extraordinary breadth of Baker’s output: grand mansions and modest dwellings, churches and cathedrals, law courts, schools, universities, public buildings serving both elite and ordinary communities.

Northwards, Parktown (The Heritage Portal)

Herbert Baker Bust at Northwards (The Heritage Portal)

There are minor factual slips—notably a lack of South African geographical precision in places—but these are small quibbles in an otherwise impressive work. The coverage of Baker’s British career is thorough and raises important questions about his relative neglect in the UK. One is left wondering why Baker has not been commemorated with a blue plaque in London, particularly given his association with T. E. Lawrence, who completed Seven Pillars of Wisdom while living in Baker’s apartment above his architectural practice.

We are left, finally, with the central conundrum that has long surrounded Baker’s reputation: why was he regarded as the greatest architect of his era in South Africa, yet occupies a more modest perch in the canon of British twentieth-century architecture? Stewart does not pretend to resolve this entirely, but his biography sharpens the question and restores Baker to serious consideration.

This book should be read not in isolation, but as a companion and extension to the foundational South African studies by Doreen Greig and Michael Keath. Taken together, these works allow Baker to be seen whole: as an imperial architect, certainly, but also as a disciplined, serious, and in many respects underrated figure. Stewart’s biography is well worth reading and will stand as a standard reference for years to come.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.