Deneys Schreiner (1923-2008) was a liberal and an academic, a scientist and a Vice Principal at Natal University (Pietermaritzburg Campus). He was known as the man with the flowing beard, which he kept in place and sprouting from his face as a personal protest against the apartheid regime. As the man aged, the beard turned from black to Santa Claus white. He shaved off his beard after the first South African democratic elections in April 1994, but by that stage of his life the beard had become an expression of his personality and there is a delightful family photo of the Schreiner Clan in December 1999 with the famous beard back in place.

This biography was commissioned by Else Schreiner, wife of Deneys after his passing. Graham Dominy rose to the occasion. Dominy met Schreiner as a first year student and grew close to him over the years but always addressed him as “Prof”. It was a title of respect for this distinguished South African and the blend of respect and admiration shines through in this fond tribute. Dominy is an archivist and Research Fellow at the University of South Africa. His skill as an historian and researcher in probing, exploring and telling the life story of Deneys Schreiner gives us a character sketch of a passionate South African who lived his liberal thinking almost as a religion. Schreiner earned his place in the political history of South Africa because he thought through, wrote and argued the political and constitutional options possible in the 1970s and 80s.

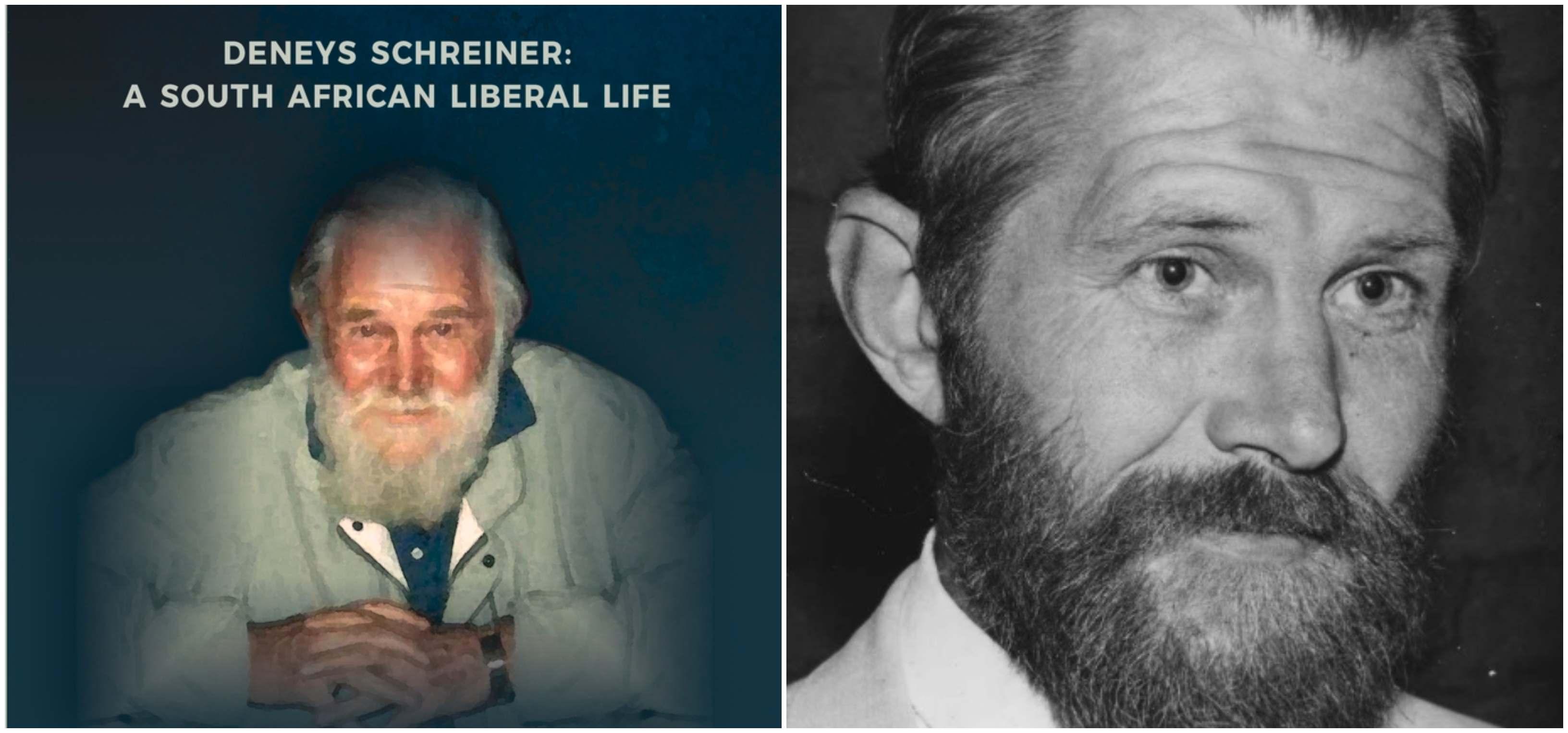

Book Cover

Looking back from the third decade of the twenty first century, and caught up in the current crises around political corruption and whether the ANC has a future as a government, we all too quickly forget that the mid to late decades of the twentieth century marched to their own beat and fought different battles. Those years were defined by the uprisings of Sharpeville in 1960 and Soweto in 1976, and then came the even more turbulent and violent eighties and early nineties. There were many who debated possible solutions and directions for change and sometimes they chose strange bedfellows.

Deneys Schreiner chose an association with Manogsuthu Buthelezi, the chief minister of the KwaZulu Homeland Territorial Authority. He is remembered as the man who chaired Buthelezi’s Commission on developing a new constitution for KwaZulu and old Natal. Schreiner was a practical man and wanted to be an active player in advancing with alternative political models for an anticipated new South Africa. Like Alan Paton he was a member of the Liberal Party in the fifties but beyond the disbandment of the party in 1968, Schreiner remained a liberal all his life and his life was defined by his liberal values and service to others. He was a wise, capable organizer; a good listener. He was a social activist who made a contribution to the shaping of a democratic South Africa but the subtext of this biography is also a commentary on the strengths of librarlism in South Africa as well as its limits.

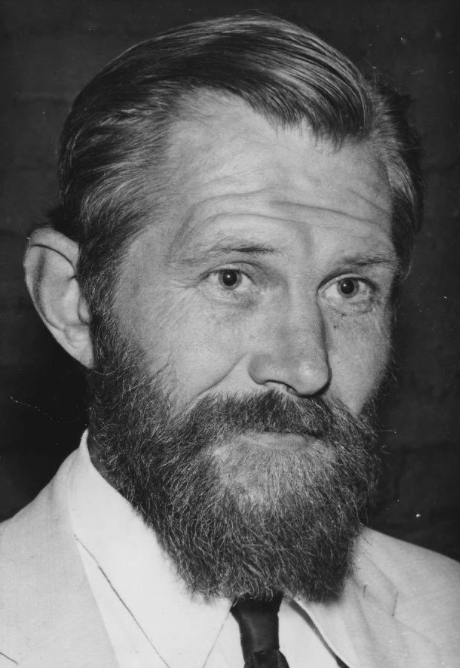

Deneys Schreiner

Deneys Schreiner was educated at St John’s College in Johannesburg and in 1940 went on to study chemistry at the University of the Witwatersrand. On completing his three year undergraduate degree, he joined the South African army and volunteered for military service “up north” in the 6th Armoured Division. Dominy provides an interesting account based on family letters of Deneys’s war time experiences in Egypt and then in Italy. He seems to have had “a good war” as he was not captured or killed but was able to explore the beauties of the Italian countryside and see Rome. After the War, Deneys studied science at Cambridge. He married Else Kops in 1949, his life long soul mate. He was a family man. The biography is also the story of a successful marriage and is dedicated to Else Schreiner, who died in 2018. She was a strong woman in her own right.

St John's College (The Heritage Portal)

Wits Great Hall (The Heritage Portal)

Schreiner embarked on a career as an academic in science in Pennsylvania in the US, a spell at Wits in the fifties and then he enjoyed a career at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg. Deneys Schreiner’s life revolved around his family (the couple had four children ), university teaching and management and political activism. Deneys joined the Liberal Party and Else joined the Black Sash. The family faced tragedy when their eldest son Oliver was killed in Cambridge in a cycling accident in 1978. How do parents recover when a child is lost in such circumstances? The book is also about personal fortitude and courage in finding the will power to continue with life and work after heartache. The biography probes what it meant to be a university leader (albeit of a satellite campus of Natal University). Those were years of turmoil and protest as the University of Natal was one of the “open” English speaking universities that opposed apartheid; students had to be bailed out, and campus parking problems solved.

In the early 1980s, Mangosutho Buthelezi approached Schreiner to chair what became the Buthelezi Commission and this biography adds to the recounting of political possibilities of that decade by explaining why both Buthelezi and Schreiner were important in the attempt to break the apartheid logjam. The two chapters on the Commission and the aftermath are significant ones in capturing an underplayed, quite complex effort pushing for change but also regional accommodation.

Mangosutho Buthelezi

Deneys and Else’s daughter Jennifer was a political activist who chose the path of revolution and violence placing car bombs in Cape Town. I think that path required courage of a different sort but Dominy says little about how her parents felt about those choices. In 1987, Jennifer found herself arrested, imprisoned, coping with solitary confinement. It was every South African’s parents’ nightmare and Else published her account in Time Stretching Fear. The trial was a long one and finally Jenny and her co-accused Tony Yengeni were indemnified for their actions in 1991. Dominy tells the story of these horrible years from the perspective of the parents and again how Deneys responded with love and handling the practicalities of supporting a daughter and not passing judgement.

Schreiner came from a distinguished family deeply embedded in the South African past. A biography and a family story provides another prism through which to view a country’s history. A good biographer looks for ancestral roots and places the story of an individual in the context of the forces that explain why an individual makes certain life choices. This biography reminded me that we are the product of our ancestry and earlier generations but each of us has personal choices to make in our own lifetimes. The first generation of South African Schreiners were immigrants from Germany. Thereafter through four generations, this illustrious family produced men and women who achieved fame.

The grandfather of Deneys, Gottlob Schreiner (1814-1876) was a missionary of the London Missionary Society and later practiced as a Wesleyan. The son of Gottlob and his wife Rebecca was William P Schreiner (1857–1919). He trained as a lawyer in England and moved from the position of legal adviser to the British governor of the Cape Colony into Cape politics and became Cape Prime Minister in 1898. W P Schreiner remained in that office until maneuvered out of that position by Milner in 1900. W P Schreiner returned to political life in 1908 and participated in negotiations for a united South Africa. Olive Schreiner (1855-1920), whose fame rested on her great novel of South Africa, The Story of an African Farm, published under the nom de plume, Ralph Irons in 1883 , was the sister of W P Schreiner.

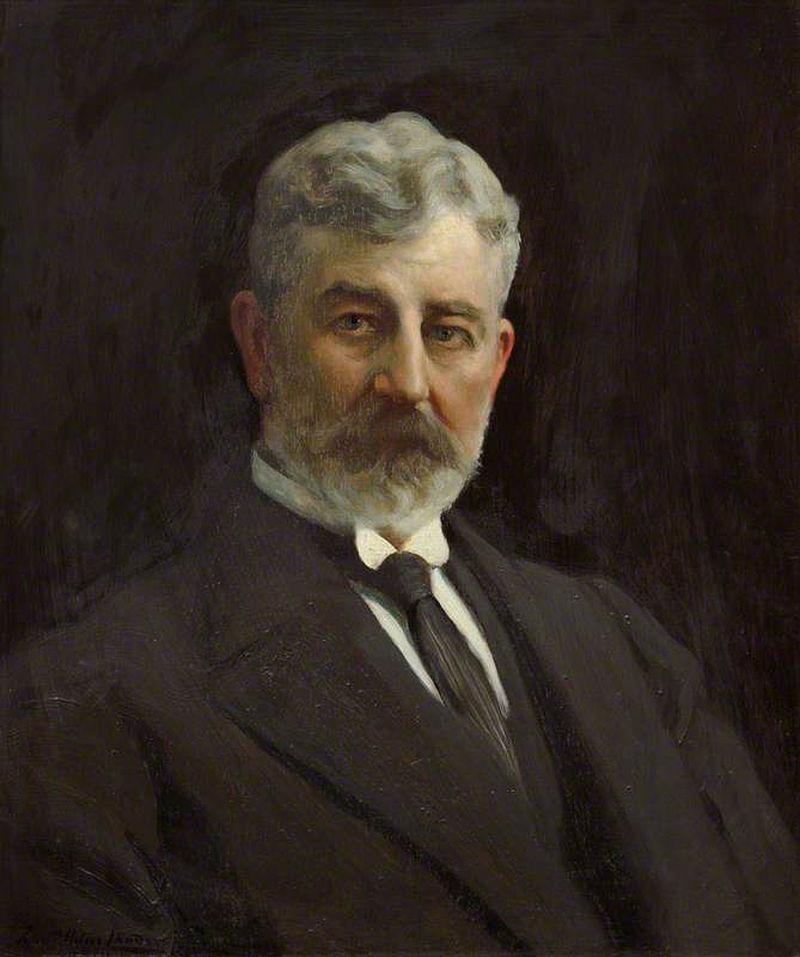

William P Schreiner (Wikipedia)

Book Cover

Judge Oliver D Schreiner (1890-1980) was the son of W P Schreiner. OD Schreiner studied law at Cambridge but in view of the feud of his father with Rhodes, the family would never have asked for nor accepted a Rhodes scholarship. Oliver’s studies were interrupted by the First World War; he was commissioned into the British Army and served with the Northamptonshire Regiment and the South Wales Borderers. He was wounded in the right arm at Trônes Wood during the Battle of the Somme, and received the Military Cross. He returned to South Africa after the war on completion of his studies in law. Oliver Schreiner was the man known for being passed over for the position of Chief Justice because of his principled stands in legal affairs – such as opening the bar to all races in 1923. He was the Chief Justice the country should have had.

In 1950 the National Party government of DF Malan passed the Separate Representation of Voters Bill with the objective of removing coloured voters from the common voters’ roll in the Cape Province. OD and his fellow judges in the Appellate Division struck down that 1950 Act in 1952 but the Nat government proceeded to turn Parliament into a High Court to give it the constitutional power to overrule the Appellate Division. The fight between Parliament and the Judiciary culminated in the expansion of the Appellate bench from five to ten judges now all appointed by the apartheid state. Finally in 1956 the Separate representation Bill was passed; that unwavering dissent by OD Schreiner meant that he was not appointed Chief Justice. It was an injustice never forgotten by liberals. OD Schreiner was honoured by the University of the Witwatersrand with the Law School named for him and his memory commemorated in the annual Oliver Schreiner Memorial Lecture. Oliver Schreiner was the Chancellor of Wits between 1962 and 1974. The 2008 Schreiner lecture was delivered by Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke, who is another principled man and again was someone who should have been appointed Chief Justice, but like Schreiner political partisanship trumped right.

OD Schreiner was the father of Deneys Schreiner. The story of the family is the context to the biography of Deneys because this remarkable family who have played public roles in church, politics, law and academe over five generations. A remarkable achievement where a liberal position meant different things across the decades but there was a consistency in inherited intelligence, public service and independent thought. One admires the Schreiners as a clan for people who had the courage of their convictions.

This is an interesting sympathetic biography that makes a contribution to the history of South Africa in the 20th century. The author examines the role of one man and his family both in developing a liberal ethos at the University of Natal but was aware of his lineage and was not afraid to speak truth to power.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.