Peter Elliott, the author of this biography, is the great grandson of Sir Thomas Muir; Elliott has used the family connection and his personal archives to write an interesting biography of a now mainly forgotten Cape colonial educational administrator and mathematician. This is an even-handed biography full of appeal and does not shy away from the points of controversy around Muir’s attitudes and how policies of a century ago are to be evaluated today. The colonial roots of education are open to modern criticism because it was indeed British and colonial but there were many positive aspects to that legacy and the best of South African schools still embrace and celebrate their history and traditions. The architectural heritage in more than 100 schools is extraordinary and a huge debt is owed to Sir Thomas Muir on that account alone. We are reminded that “British” also meant “Scottish” and the contribution of a distinctive Scottish educational approach means a more nuanced interpretation.

Muir was also a mathematician of some distinction. Today, Thomas Muir is remembered because he bequeathed his personal mathematics journal and books to the South African Public Library; Muir College in Uitenhage was named in his honour and the Thomas Muir Chair of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow was established in 1966. A Muir Street in Cape Town survives and Muir’s name is probably to be found in other towns and on foundation stones of many school buildings. Muir apparently had a cabinet full of keys and trowels; mementoes for all the buildings he opened.

Googling the name Thomas Muir is more likely to direct one to Muir the mathematician rather than to Muir, the Cape colonial educationist but this biography gives us a rounded picture of the character and life of the man.

Book Cover

To get a measure of the man the author starts by exploring the early years of a mid-Victorian childhood in Scotland. Many years later Muir drew on his own experiences in Scotland to inform his educational reforms at the Cape. Muir was born in Lanarkshire in 1844, he was the son of an agricultural labourer, George Muir. His father died young, his family was poor but his mother Mary was a strong and resourceful woman and the family survived. Muir rose above his background because he was a clever talented boy who excelled in all school subjects. But he also owed much to the Scottish culture that enabled ability to be recognized. Muir pursued studies in mathematics and qualified as a mathematician. Apparently Muir also studied mathematics in Berlin and Göttingen but those years are not explored. His professional career started as a teacher in Scotland, and he progressed in academic positions at St Andrews University and at Glasgow High School. He married Mary Brown and had four children. On the surface he was successful, contented and well established in his homeland but he chose to emigrate to South Africa.

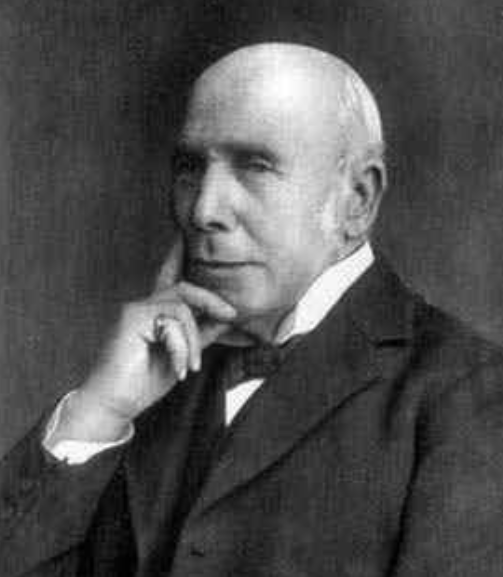

Sir Thomas Muir (Wikipedia)

The first 20 pages deal with the first nearly five decades of Muir’s life. Why did Muir choose a career as a school master rather than an academic career at the University of Glasgow or St Andrews and why when mathematics was clearly his first love did academic research slip into second place? His talents and achievements in mathematics were recognized. Muir was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Glasgow (and he always used the title Dr.) and he was a fellow of the Royal Society.

It was only in 1892 at mid career when Muir was already aged 48, that he was offered an appointment by Rhodes as the Superintendent-General of Education of the Cape Colony. Rhodes was Cape Prime Minister from 1890 to 1896 and Muir was a Rhodes man from the start; he was an admirer of Rhodes and a lieutenant for the Rhodes vision. Settling in Cape Town, Muir’s life took on a new direction; his task was to take charge of school education in the Cape Colony. Muir established a reputation as an authoritarian but a highly capable organizer of schools, primary and high school education and teacher training. In the year he retired, at the age of 70 in 1915 he was knighted for his services to science. He did not return to Scotland but built a house in Rondebosch and lived there until his death in 1934.

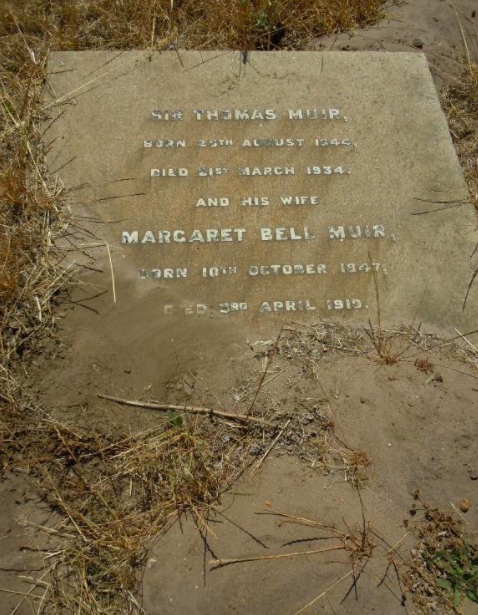

Grave of Sir Thomas Muir (Alta Griffiths)

Muir in fact had a dual career - a practical administrator and civil servant in Education and a scientist who kept up his research in mathematics. It is interesting to learn that Muir’s achievements were recognized in his lifetime and he filled a wide range of positions as a public figure at the Cape. The chapter on philanthropy and leisure could have delved into Muir’s other leadership roles such as his membership of a geological survey of the Cape Colony or his being a foundation member of the SA Association for the Advancement of Science. Muir served on the council of the University of the Cape of Good Hope from 1892 to 1913 and also served as a Vice Chancellor of the University of the Cape of Good Hope. He was an examiner in mathematics at the university and was a trustee of the South African Public Library. It was an impressive record of public service. I am also impressed by the fact that Muir was a contributor to the 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica; this is the most important of the E B editions and the only one really worth collecting today.

In his new career position at the Cape that spanned 23 years, Muir surveyed schools and districts, rural and urban. He pushed for compulsory education and he introduced reforms to improve quality. The primary school curriculum was broadened to include a wider range of subjects such as singing, needlework, woodwork, drawing, nature study and domestic science. He placed emphasis on better teacher qualifications. Ferguson says that Muir strengthened local interests by promoting a school board system; Elliott seems to think that Muir weakened local authority so clearly this is an area for further analysis.

I wondered why Elliott chose the sobriquet, ‘lad o’ pairts’. I doubt that Thomas Muir would have described himself as a ‘lad o’ pairts’. He comes across as someone who turned his back on his humble origins, was upwardly mobile and very self-consciously joined the middle classes. Perhaps that was the appeal of Cape Town and life in the colonies, where he could shift into “society” far more readily than in Scotland.

The phrase “lad o’ pairts” is Scottish; it is a nifty expression used to describe a clever fellow of talent, from a poor background who has made good. It signals an ideal encouraged by the 19th century Scottish educational system, a boy who has acquired a broad knowledge and is a practical all-rounder. Such a boy growing to manhood could be a desirable colonial pioneer in Africa. Scotland, despite its more limited resources, had a superior educational system and boasted four ancient universities. Scottish education was a ready export to the colonies.

Adam Fox, in an article in The Guardian in 2002, gives us a good introduction to the benefits of Scottish education as opposed to an English education. Following the Reformation and the legacy of John Knox, every parish by the 17th century had a local school. At the age of 15, bright boys could move on to a university. Scottish universities were far cheaper than Oxford or Cambridge. Edinburgh, Glasgow, St Andrews and Aberdeen were all ancient universities of status and tradition. Scottish society was more open to social progression and working class children could study for a profession. Law, divinity or medicine were the obvious choices. There was a distinctive Scottish university tradition. These universities were more inclusive and welcomed dissenters and Catholics, whereas the English universities excluded them. There was easier access, more bursaries were available and hence there were many clever young Scots who could rise above their humble background even if their fathers were agricultural labourers, or miners or fishermen. If there were fewer work opportunities in Scotland, London or emigration was an option and a professional qualification pitched such men into government or missionary service abroad. I can think of other Scots who were “lad o’ pairts” – Ramsay MacDonald from Lossiemouth became British Prime Minister, B John Buchan (later Lord Tweedsmuir) became a civil servant and member of Milner’s Kindergarten responsible for the reshaping of the Transvaal after the Anglo Boer war. I wondered if Buchan knew or approved of Muir as a fellow Scot also laboring in the colonial vineyard.

The 1907 school building of Oudtshoorn Boys’ High School. Today it is a museum. (Wikipedia)

Muir was responsible for the sizeable school building programme in the Cape between 1900 and 1915. 120 new schools or buildings were erected during Muir’s tenure. Facetiously called “Dr Muir’s Palaces”, the majority were schools serving the better off white community because better school buildings needed local finance and the trick was to raise the capital with redeemable loans; only affluent communities could fund such “palaces”. Engaged communities committed to the future generation had to buy into Muir’s scheme and he achieved that support and with support came success.

I would have liked to have known more about the architecture and architects of these schools as well as the economics of the school building programme. Only two architectural firms are mentioned – William White-Cooper and Parker & Forsyth. These buildings were substantial, solidly built in brick, very much in Edwardian style – often august and ornate with turrets, pediments, gables and chimneys. The school and the church and perhaps the town hall (if there was one ) were the prominent town buildings. The Muir influence can be picked up in books on historic schools, but there the story of the particular school takes priority and the overview is lost. This biography covers all aspects of the man.

Vintage postcard of Rocklands High school for Girls in Cradock

Today there is plenty of room for debate and discussion about the nature of colonial education and what this meant for South African society black and white. What was the legacy of an education system that was racist and sexist and strongly pro-British? As mentioned, Muir came to the Cape because he fell under the spell of Rhodes; he succeeded Sir Langham Dale as Superintendent of General Education. He made a good impression and Rhodes wanted fresh blood; Muir offered organization skills, and ideas about introducing the Scottish model of education into the Cape Colony. He took charge of meetings, steered committee decisions to his strategic desired position.

Could Muir have achieved more? He was a man of his time. He wanted to get things done and comes across as a sympathetic man to his close friends and cronies but intolerant of boring people or those who disagreed with him. Muir though was ahead of his time as a bureaucrat, a capable administrator and an organizer. However, there is a racial dimension. The focus of Muir’s educational reforms was on white educational improvements and whilst education for Africans was provided, it was far more limited. Black education was taken to Standard 4 level with the principal skills being reading, writing and arithmetic. Rural education, whether for white or blacks was backwards and greater resources needed to be allocated to poor schools for poor whites. While Muir understood the essential that a poor child could have a better chance because of a better education, not all poor children fitted his model. Muir was far less interested in the Afrikaans language question, bilingualism, mission schools or schooling in general for non-white pupils. The school building programme benefitted a much larger number of white pupils once compulsory education was introduced, but whilst there was not total neglect of black education, it was second in line. The popular view and one shared by Muir, was that Africans had a very restricted role to play in colonial society and the trajectory to a profession was much harder for a black child than a white. In his day there was little chance for a black boy to become a “lad o’ pairts’” in South Africa nor for a girl whether white or black to become a 'Lass o’ pairts’.

This study of Muir challenges the interpretation of the Cape as a colony of liberal thinkers, that view of “the Cape liberal”. When the Union of South Africa was created in 1910, primary and secondary education remained a provincial responsibility which meant that old colonial systems continued. Muir did not retire until 1915 but it is evident that by the last years of his career his views were challenged and he had to work with another autocratic, Sir Frederik de Waal, appointed as the provincial administrator. Muir sought new allies and in Elliott’s opinion some were strange bed fellows such as J W Jagger.

This biography is also a family story and provides a family tree over four generations. It is an interesting family because the daughters of the next generation were far more successful than the sons who must have disappointed their father.

The bibliography is comprehensive but mixes primary and secondary sources.

This biography offers double value because it combines both a biography and shares Muir’s own diaries written up describing his school inspection tours and those happy celebratory new school openings. These diaries record journeys by train throughout the Cape on tours of inspection between 1909 and 1912. The diaries, forming part 2 of the book, provide a fascinating account of train travels at the time of Union. The diaries are a personal record written solely for Muir himself and therefore are intimate and give a far richer picture of Muir. Such documents have an archival first hand flavor and are a special delight of this book because they give a first hand perspective of travel, meeting people, the experience of local hospitality and the friendships of an inner working group or what Muir thought of a young silly female teacher attempting suicide. The diary, also presents a great many pictures of railway stations, railway tracks and sidings. So the book will have a secondary appeal to railway enthusiasts.

There are some excellent photographs of some of the Muir enabled new schools such as the Erica primary school of Port Elizabeth, the Cradock Girls’ High School, the high school in Uitenhage which became Muir College, Oudtshoorn Boys High School, the Prestwich Street Primary school, the Mossel Bay Boys’ public school, the Worcester Girls High and the Rondebosch Boys High, the Grahamstown Training college, the Prieska Public school and the Tiger Koof school in Vryburg.

Two useful biographical sketches of Muir should be read as a supplement to this biography and could have enhanced the book had they been included. The S2A3 biographical database of Southern African Science by Prof C Plug and an entry in the Dictionary of South African Biography vol 1, 1968 by W T Ferguson. Elliott uses the Plug biography but attributes the Ferguson DSAB to a C H Rautenbach.

Elliott is not sufficiently familiar with the history of education in South Africa more broadly to relate the Cape experience to that of Natal or the two Boer republics or other parts of Southern Africa, but then that was clearly not his brief. So the book is probably best read as a biography with some pointers to a better understanding of how Cape education evolved.

Muir’s was a distinguished career. He was evidently ambitious and talented. His was a long productive and fruitful life. But there are undertones and a number of unknowns in this biography. The marriage of Thomas Muir to Margaret Bell (Maggie) produced four children but she seems to have been sickly, anxious and unhappy and did not travel with her husband on his trips to the cape hinterlands. This left Muir to enjoy the company of others. He was close friends with a much younger teacher, a Miss Alice Cogan and after the death of Mrs Muir it was Alice who shared his home in retirement but was not provided for at his death. The father-son relationship with his two sons appears to have broken down and the sons went their own way.

Muir was a renowned mathematician who took his mathematics seriously. From 1906 onwards he published five-volumes on the history and theory of determinants, the final part (1929) taking the theory to 1920. In his quite long retirement from 1915 until his death in 1934, Muir returned to his mathematics research. A further book followed in 1930.

In summary, this is a solid biography that adds to the literature on South African educational history. The travel diaries are alone worthy of note but it is the biography that then gives context to the personal diaries. At R250 the book is good value for money and I recommend it as a book that will stretch the reader into thinking about education and its roots through the life story of one man.

Peter Elliott, Thomas Muir's great-grandson, is the author of Nita Spilhaus and Her Artist Friends in the Cape and Constance: one road to take, the life and photography of Constance Stuart Larrabee. Peter seems to be fortunate in his ancestry as he has made a writing career out of discovering and recovering the stories of his interesting family. Elliott’s other books can also be purchased form Clarke’s bookshop.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.