This is an Afrikaans book and although we are all supposed to be multilingual in South Africa (after all we have 11 official languages) and so many of us learnt Afrikaans at school, Afrikaans books are not my forte. This was one I read with dictionary to hand and with great enthusiasm. I congratulate the authors, Menache and Wolff. The photographs are a treat and the text is actually easy reading.

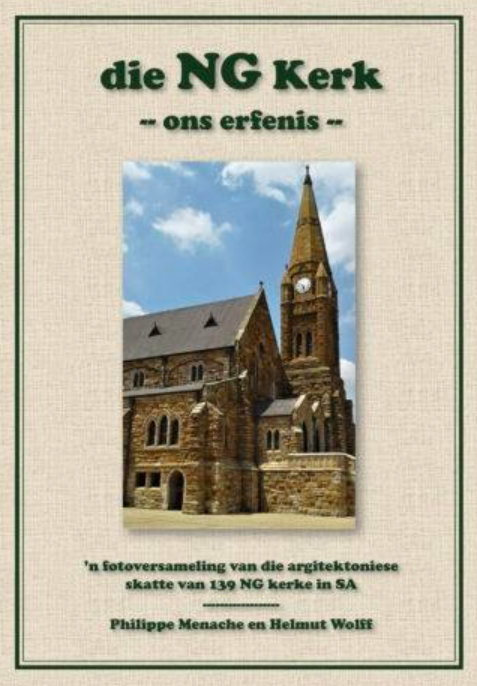

Book Cover

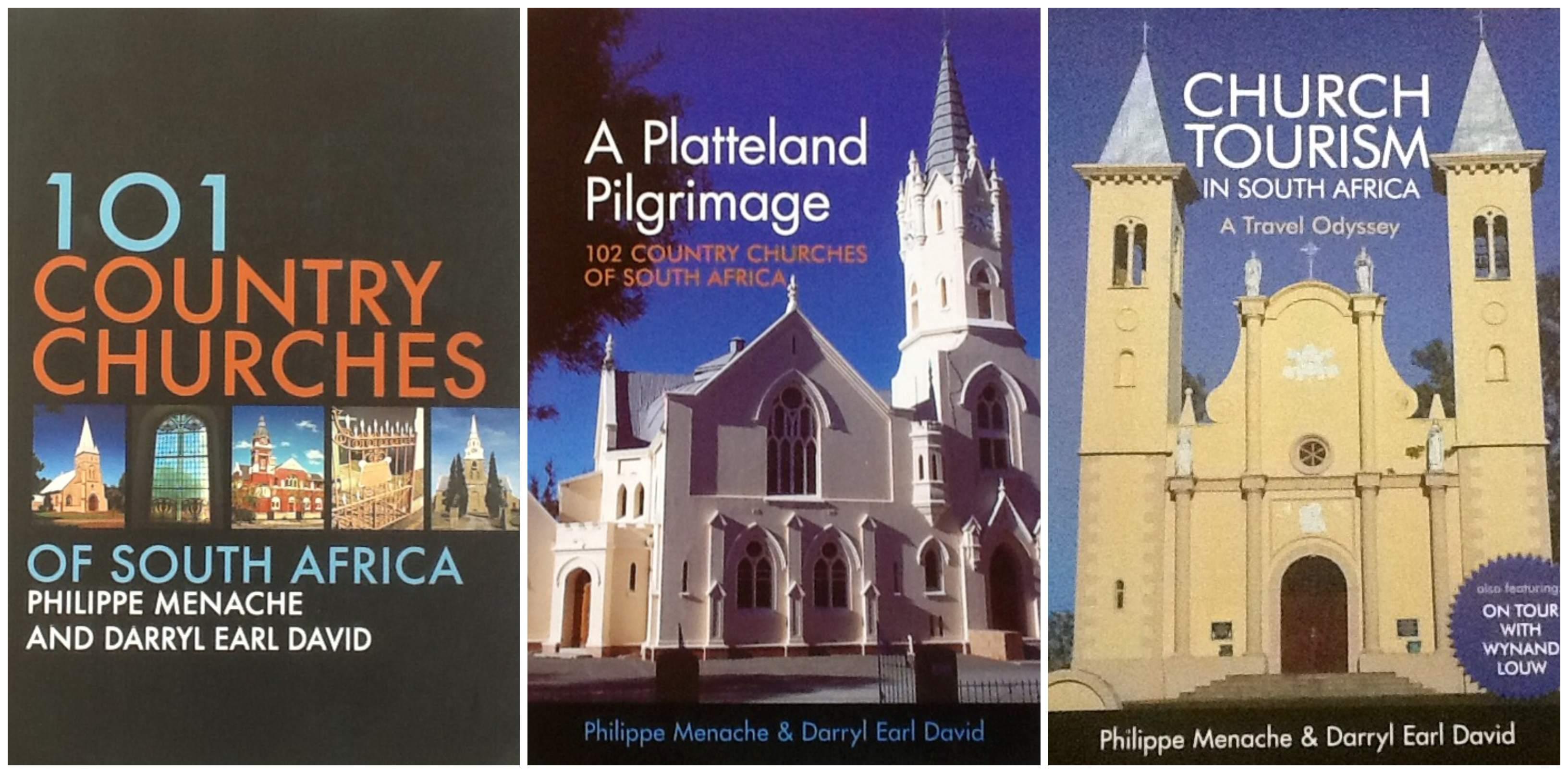

Philippe Menache has established his reputation as the man who has travelled South Africa in search of country churches. Together with Darryl Earl David he photographed and wrote about the churches of all denominations to be found in the small towns and villages South Africa. He and Daryl invented the travel genre of church tourism. The three delightful earlier books were: 101 Country Churches of South Africa (2010), A Platteland Pilgrimage: 102 Country Churches of South Africa (2012) and Church Tourism in South Africa: A Travel Odyssey (2015). These titles sold out speedily and shifted into the collectable category. Gorgeous photographs matched well researched text and sought to explore the architecture and architects of the varied styles and materials used in the many churches - Anglican, Presbyterian, Lutheran and Dutch Reform churches were put on the travel agenda with colourful maps to set routes. Together the three earlier books brought a strong message to readers – open your eyes, look around and celebrate the unique South African church architecture.

Book Covers

In this new book, Philippe Menache, whose profession was that of a banker, stays with the same subject but has teamed up with Helmut Wolff, by profession a scientific farmer, to concentrate on the NG or Dutch Reformed Church buildings. Menache and Wolff cover churches from A to Z, from Aberdeen to Zastron. Both are enthusiastic photographic hobbyists and have travelled South Africa in search of their 139 churches. The layout gives each church half a page (e.g. Hanover), a page (e.g. George) or even three pages (e.g. Graaff-Reinet).

The Graaff-Reinet Church (Wikipedia)

Philippe is clearly also a linguist but his book will appeal to an audience beyond the tourist. In addition to church enthusiasts, there are a few other categories of readers who ought to know about this book: the museum fraternity, the architectural profession and the heritage campaigners. All will find this to be a book that fills in gaps and adds to knowledge. Africana book collectors will want to add this title to their collections. Noting that these types of titles have short print runs, it will pass rapidly into the South African collectable category. However, the Afrikaans language medium will mean that other than in the Netherlands, there is unlikely to be much of an overseas market. This is a pity because a study of the NG Kerk reveals so much about the history of a people who gave the world apartheid and yet there’s a cultural core, a literature and an architecture that makes one reflect on how and why so many churches were built in both the 19th and the 20th centuries.

The evidence that the early founders of the towns and settlements rooted their pioneering spirit in church and God is to be found in these churches. Most towns in the country, no matter how remote or small have a NG church and in all probability, four or five other churches, once missions and other denominations arrived. Each church is different and the styles of architecture varied and eclectic but when you pass through the towns and villages of South Africa, from Welkom to Howick, there is no risk of not recognizing a church. Churches aspire and inspire and are the architectural treasures and visible statements of settler arrival: a church brought together a community. When a church was built it made a statement; that the town was permanent. Towns were planned around church squares and market squares. The place was no longer a temporary camp of wagons on a trek but signalled that a settlement had been founded and people were here to put down roots. A place might have started as a village and town status developed; church squares were central and large and included a church yard, space for graves and perhaps a garden.

Sometimes a church was the first important building erected on a farm and then the town grew up around the church. Hanover, halfway between Cape Town and Johannesburg in the Northern Cape is an example. The church was often the most important building in the town; religious life bound people into communities with heart, soul and caring in the towns and the surrounding farms. In the Dutch Reformed churches, “Nagmal” was when people from surrounding farms came to town to celebrate the sacrament of Holy Communion, an event usually held four times a year. It brought communities together for both a religious and a social purpose. Such occasions were the building blocks of the “gemeente” (or congregation); the church was august and was the focal point and epicentre of the gathering and a people who were frontiersmen, trekkers, staunch in their religion, rural but not uncultivated. Religion but even more significantly language and cultural roots are expressed in that word Gemeente. It means a lot more than a congregation. Churches were man-made sacred places to worship the Lord but also to find tranquillity and stillness for the rejuvenation of the soul. For me a church, mosque or synagogue is special because of that numinous sanctified atmosphere. We celebrate the achievements of the architect, the vision of the creators and the essence of faith. Dr Dewyk Ungerer in the Foreword (Voorwoord) makes the point that the “geemeente” is the vehicle for and the protector of truth. Ungerer sums up the value of a church in a town - stability, permanence, service of a greater good, the image of beauty in a place; a church is an expression of identity and place.

I became interested in Dutch Reformed Church history because Hermann Kallenbach designed such churches. He was an immigrant German architect who came to South Africa in 1896. He acquired the right partners and had the entrepreneurial flair and crossed boundaries to become the architect of a number of religious buildings including a synagogue. There was a body of productive work in the period 1903 (post South African War) and 1913. I am researching the architecture of Hermann Kallenbach and his partners Arthur Reynolds, William Henry Ford and later Alexander Kennedy. The Kallenbach permutations of partnerships designed the Krugersdorp synagogue, but also the Fairview NG Kerk in Johannesburg, plus the Greek Orthodox church (now the Cathedral), the First Christian Science Church also on the eastern side of the city. In addition there were a number of Dutch Reformed country town NG churches - Laingsburg, Thaba Nchu, Riversdal, Barkley East as well as Hanover. The puzzle though is how much reliance was placed on the local design architect – supervising the project and on the spot and how much attribution should go to the city architect with a string of attributions and how much was the work of Kallenbach? It is a question I am not as yet able to answer.

Dutch Reformed Church Fairview (Kathy Munro)

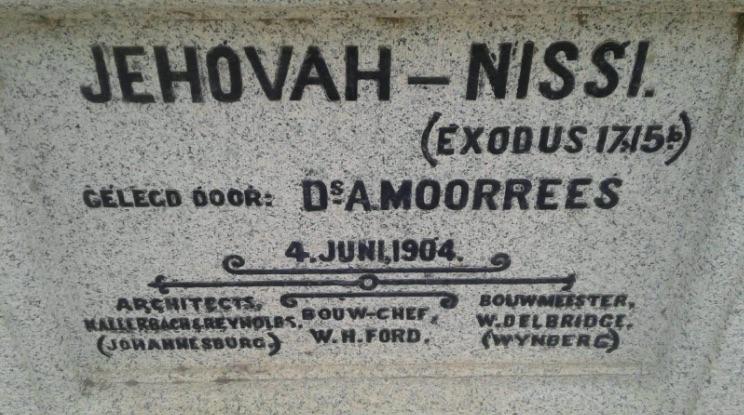

Laingsburg is an interesting case study – a 1904 church designed by Hermann Kallenbach and Reynolds (of Johannesburg) with William Henry Ford (originally from Australia) described on the foundation stone as “bouw chef” and William Delbridge of Wynberg in Cape town as the builder. The Laingsburg Church is historically important because it survived the Great Flood of 1981 when over 100 people lost their lives.

Laingsburg Church Foundation Stone (Kathy Munro)

Views of Laingsburg Church (Philippe Menache)

I visited the Hanover NG Kerk on two trips to the Cape in October (for the Swellendam Heritage Conference and then the Book Bedonnered Festival at Richmond). It was well worth stopping at Hanover to catch the atmosphere of the town; the dominance of the high spire of the church on the vast church square and the glorious interior with its fine stained glass windows and beautiful woodwork on the pulpit and the baptismal font. We met the curator of the church, Babsie and had an instant connection when together we could share our enthusiasm for the glories of this church.

Hanover Dutch Reformed Church (Kathy Munro)

Inside the Hanover Church (Kathy Munro)

Hanover Church Pulpit (Kathy Munro)

I have often found that church histories place emphasis on the pastoral leadership, the dominees who led their flock and there is only limited coverage of the architects and architecture. Yet it is the architecture that endures and is an expression of purpose, willpower and resources. This book fills a gap on church architecture though I am unable to assess what percentage of the total number of churches feature in this book.

It is worth reflecting on the economics of church construction; faith alone does not build an architectural gem. I marvel at the capital invested in the church and the extraordinary commitment of farmers to erect a beautiful building meant to endure. The Dutch Reformed or N G Kerke were and still are the most prominent. Churches expressed architectural talent and traditions imported from abroad but overlaid with a South African interpretation. Churches show the fine skills of stone masons, builders, carpenters - in fact all of the building trades, showing sophistication and complexity in design and creation. Churches blended local stone - such as granite and sandstone and imported timber or organ or clocks and bells. It was a tradition to combine a bell and a prominent clock and the church clock was visible to all and let people know the time when wrist watches were a rarity.

This volume is a photographic record of 139 Dutch Reformed churches in South Africa with a brief introduction to the town, the church and the architect. It provides an important record at a moment in time when congregations are dwindling and there are doubts about the sustainability and survival of many of these magnificent buildings. NG Kerke survive in country towns but in the city many churches have been converted to mosques or temples. Churches which were meant to bring up to 2000 people together for a Sunday service might battle today to drawn together a few hundred congregants.

This book reminds the heritage communitiy that these churches need to become provincial monuments. Their history, including the architecture, needs to be documented. The book is a celebration of the churches and their architects; men such as Charles Freeman, William Henry Ford, Hermann Kallenbach, Johannes Rienk Burg, Walter Donaldson, Gerard Moerdyk, Carl Otto Hager, Wynand Hendrik Louw, Folkert Hesse and Francois Hesse and John Gaisford and I am delighted to see the box inserts on each of these architects.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.