It would be true to state that, from a legislative and practical point of view, historical conservation in this country is an unmitigated disaster, and has been one since the demise of the old National Monuments Council in 1999. For all its ideological faults and Broederbond associations the NMC had a national infrastructure which its successor, the South African Heritage Resources Agency, SAHRA, had every opportunity of taking over and transforming to meet the needs of the new South African democracy. Instead SAHRA abandoned its regional structures, and retreated to its offices in the Western Cape which are now populated by insecure incompetents more concerned with drawing a salary than in doing the work they are being paid to do. Most of its staff is concerned with issues other than the built environment, and its Council, where most of the problems probably lie, is more focused upon the holding of meetings in airports than in providing effective leadership at a national level.

Today the only regional structures that are providing a proper support infrastructure to conservation efforts are the Western Cape and, partly, KwaZulu-Natal, and while the establishment of regional heritage bodies is a factor of provincial government, SAHRA has failed to provide the leadership and driving force to make these a reality. In Limpopo, for example, its heritage staff consists of two persons who know nothing about conservation, and seldom travel beyond their offices in Polokwane.

Had SAHRA’s management been in any way capable of meeting its functional duties, then it would be taking action, as a matter of urgency, to head off the pending disaster facing our cities through the blind imposition of its 60-year protection rule. In its terms, in 2006 the bulk of South Africa’s post-war housing became “protected”, swamping municipalities with administrative work they had neither the staff nor the knowledge to handle. As most of this housing stock was generally non-descript and of little historical value, a solution should have been simple to implement, but it was never applied.

Many buildings on Cape Town's famous Long Street are already protected (The Heritage Portal)

By 2020 large parts of the CBDs in Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and Pretoria will be likewise protected, and the fear has been voiced that this will bring property development in these areas to a grinding halt. This will result in a concomitant loss of investment, a reduction in new building development, and a drop in property prices. It will also seriously affect any nascent efforts to restructure the Apartheid City and bring to an end the structural inequality it enforces upon its residents. The national press raised this issue in 2013, but not a single voice could be found at SAHRA to reassure the public that the matter was receiving its most immediate attention.

More recently there has been talk of scrapping the 60-year clause which, under current conditions, will also do away with the need to have existing heritage agencies altogether, but will not remove the need for an active and competent national heritage body capable of administering the Act and of taking proactive action to safeguard the future of our historical built environments.

In terms of the Heritage Act SAHRA was also charged with the creation of a national register of heritage resources but, fourteen years down the line, little such work has been done. Instead the Agency has left matters in the hands of local authorities who, understandably, have been reluctant to allocate precious budget resources to surveys they do not perceive, or understand, to be of any immediate practical value. To the best of my knowledge Durban is the first, and so far only, major municipality in the country to begin this task, and even then its efforts to date have been limited to one small area of the city. A handful of smaller municipalities, predictably all located in the Western Cape, have also conducted comprehensive surveys.

SAHRA has also failed to promote the establishment of regional representative bodies in most of the nine provinces, and in places such as KwaZulu-Natal, it has mandated its work to AMAFA, a provincial agency with few effective powers. In desperation AMAFA recently announced that it would now accredit Conservation Practitioners according to criteria it has invented and has no legal right to enforce. Attempts to organize regional and national workshops to regulate research methodologies towards the creation of a National Heritage Resource Register have been met with dumb silence from Cape Town.

City Hall Johannesburg - One of the Projects covered in the book (Photo: Mark Straw)

It is no wonder then that today the National Heritage Act of 1999, promulgated in 2000, is a dead letter, and that local authorities, municipalities, private developers and individuals generally ignore its provisions in the full knowledge that retribution is unlikely, and any penalties laughable. The list of buildings and environments lost since 1994 is heart-achingly long, and spans the country from the potential World Heritage Site at Mukumbani, in Venda, down to the very few historical buildings left standing in Uniondale. The Rissik Street post office in Johannesburg was burnt down by its security staff to hide the theft of its brass fittings, and as I write the historical Ndebele village of KwaMsiza, once a potential World Heritage Site, is under threat of demolition.

It has been said that every country has the government it deserves, but I am not entirely certain what South Africans have done to deserve the treatment that is currently being meted out to its material culture and historical heritage.

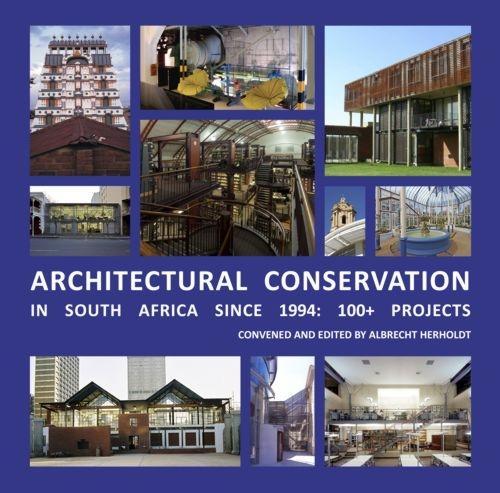

Which is why this book, conceived, compiled and edited by the fertile mind of Albrecht Herholdt, is so important. In an era where official controls have withered to hollow pronouncements, when the nation focuses upon Nkandla as a pinnacle of cultural achievement, and when the curbs upon the excesses of megalomaniac developers and self-seeking visionary architects have all but disappeared, this volume brings together more than a hundred conservation projects conceived and executed by professional architects. Despite its main urban focus, a number of projects are located in smaller towns and rural villages, and reinforce the belief that beyond every major conservation project conducted by an architect sits a score of smaller, unrecognized restorations.

The volume itself is a tour de force, 539 pages of glossy, hard paper printed in full colour, stitched and bound between hard covers, with a dust jacket. The in-house layout is excellent but with very small margins which have allowed the printer almost no room for error. To its credit, it has met this challenge, its quality controls have been excellent, and I found no signs of guillotine misalignment.

Pearson Conservatory is another project covered in the book (The Matrix)

The selling price is R650 which, thanks to generous sponsorship from Messrs Gordon Verhoef & Krause, PPC Cement, and the profession, is about one third of what it should have been. It might appear to some to be an expensive volume, but relative to its production costs, it is money well spent.

The editors and designers of this book should also be congratulated on achieving a standardized style of presentation, both in terms of graphic quality and the written word, no mean feat when we consider the wide range of contributors and the notoriously large egos prevalent in the profession.

The contents are well-structured into six fairly sensible geographical zones which, however, also emphasize the paucity of formal restoration activity taking place outside our major urban areas. Our formerly all-Caucasian countryside, the Karoo, the platteland and the highveld, barely impinge upon the book’s collective consciousness, while our African areas do not appear at all. Like Jan Smuts who saw only a dark abyss when he looked into the future of our black compatriots, it appears that our colleagues in architecture see only a void when it comes to the indigenous built environment, and all activity in this field has seemingly been abrogated to archaeologists and anthropologists. Perhaps this is attributable to the perceived lack of lucrative commissions on offer, or maybe to the fact that Gucci shoes and barefoot architecture do not make for happy companions.

Each geographical zone is introduced by a short essay which serves to contextualize the region but fails to engage in any critical discourse. Only Stephen Townsend’s foreword to the Western Cape and Surrounds makes any reference to the shortcomings of some of the projects. Nonetheless these essays assist the flow of the text from one section to the next. The Editor,Albrecht Herholdt, has provided a comprehensive, if uncritical, overview of Conservation in South Africa since 1994.

The bulk of the book is taken up by the 111 featured projects. Each entry has been allocated four pages, including one for the text, one for drawings, and a double page photographic spread. This means that the conversion and restoration of Johannesburg’s former City Hall gets the same amount of space as a set of homes in Parkhurst. No exceptions appear to have been made. Democratic? Maybe ...

Nonetheless it is here that the value of this book begins to emerge, for contrary to any comments I may have made previously, it is at this point that we begin to realize that despite the state of collapse and chaos that prevails in areas of historical conservation, South African architects individually have continued to do what they do best: mind their own business and get on with the pursuit of fine design and competent construction. Taken as a whole, the result has been a series of buildings of consistently high quality, often showing a caring and sensitive approach to restoration and to the history of the buildings concerned. The range of work is wide, spanning from conventional restoration through to the recycling, revalidation and in-fill of historical structures. Taken as a whole they present a sweeping vista of conservation which says much about the competence of the architects who completed these briefs, about the social values they represent, their scholarship, and the university education they have received.

It is also heartening to see the range of eras that is covered by their work, from the more conventional colonial architecture through to the Modern Movement. Conspicuous by their absence are buildings from the Art Deco era, which might seem to indicate that these have an enthusiastic public following and continue to be loved and cherished by their owners, while other buildings all about them have been allowed to fall into disrepair. Lovers of the Modern Movement might wish to take note.

There are, of course, a few examples which, inevitably, betray the enduring love-affair that some South African architects still entertain for Modernist ideas, and have used restoration as an excuse to impose their outdated views upon otherwise modest old structures, but these are in the minority. The volume covers work completed since 1994 which, under the circumstances, is probably apt.

One of the problems I do have with the book is the fact that all of the work has been put forward in a current and almost timeless manner. That, of course, is a factor of its style of presentation, but a number of the projects are now twenty years old, which is sufficient time for us to evaluate their socio-economic effectiveness and cultural value. One particular example I have in mind is the Red Location Heritage House, in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth, by Noero Wolff Architects, with the participation of Stephen Townsend. Earlier this year it was invaded by members of the local community protesting the lack of housing delivery in the area, and its premises were looted and extensively damaged. Although it was only completed in 2011, the building has now been closed to the public and, by all accounts, is being gradually vandalized. Under such circumstances the value of historical conservation in our society and the role of architects in its processes need to be seriously questioned.

The book also fails to distinguish between the work of qualified architectural practitioners, and that of talented amateurs. Sandra Antrobus has, single-handedly restored many notable buildings in Cradock, but, to the best of my knowledge, has never qualified as an architect. (Regrettably) there is nothing in the Architects’ Act that reserves conservation work as the sole preserve of professional architects, but her inclusion without suitable qualification alongside many of this country’s architectural firms is misleading. Given the addition of Ms Antrobus, perhaps the editorial net might have been cast somewhat wider, including some of the restoration work taking place in places such as Smithfield, Clarens, and Ficksburg, none of it under the guidance of professional architects.

The book has an Index, which is necessary and invaluable, but might have been more comprehensive and better compiled. Its entries have been listed according to a code which separates participating critics from architectural practices, placing critic Karel Bakker under B, while architect Schalk le Roux is listed under S. A collected Bibliography at the end would have given added value to the book as a reference work.

Finally the Editor might have paid tribute, however briefly, to the work of those few who conduct research in the field of architecture and related fields, who receive no formal architectural recognition, but make a valuable contribution to the body of historical conservation in this country. Published titles include “Old towns and villages of the Cape”, by Hans Fransen (2006), and “Brakdak”, by Gabriel Fagin (2008) while, more recently, work has been done in the Department of Archaeology at UCT which, I believe, will revolutionize our understanding of corbelled stone buildings in the Karoo. The inclusion of the Drakenstein Heritage Resources survey is to be welcomed. Whether the architectural profession cares to acknowledge it or not, the built environment, all built environment, creates a stage-set within which we play out daily the soap operas of our lives. Architectural historians traditionally hold that a people with a mean architecture will belabour under mean and mediocre values, while buildings with soaring spires and pinnacles will inspire their hearts and minds to greater things. And with architecture come the memories of the people and events, real and mythical, from times past, which populate the material artifacts, the built forms, the civic spaces and the environments of our time. Architecture is a continuum, and through it we inherit the thoughts and shadows and achievements of previous generations. Thus, at its most basic, historical conservation is concerned primarily with the preservation of the memories which are embodied in our built environments.

It goes without saying that such memories are constructs, fugitive and ephemeral, subject to personal interpretations and selective prejudices. But they are also integral to the built environment, and when we demolish a building, we also extinguish a whole sector of memories from our collective consciousness. Generally we leave it to historians to create the frameworks within which such memories can be stored and interpreted, but even then these are subject to current political dogma and popular opinion which mould the interpretation of facts to suit individual tastes, narrow sectarian agendas and national needs.

This is why we look to architecture to provide a solid and incontestable basis for historical fact. The motives and values of its builders may be subject to periodical contestation and revision, but the bricks and mortar live on. It is probably true to say that most people do not remember their lives as one constant flow, but rather as a sequence of events, much like beads strung out in a necklace. Architecture links our memories into a tangible continuum which gives a sense of perspective to our lives. Take away the buildings and you take away the continuum; take away that continuum and you replace it with a sense of disorientation and personal loss.

So, I may not like everything about this book, but it brings together into a collective the work of a diversity of architects, and as a collective they should feel a sense of pride and satisfaction in a job well done. At a time when we are faced with collapsing government legislation, obdurate and corrupt officials, and a ruling party that is set upon rewriting history in the worst possible terms, the work of conservation architects becomes particularly relevant.

Originally published in ArchSA

“Architectural Conservation in South Africa Since 1994” has been convened and edited by Albrecht Herholdt, and is published by DOT Matrix Publications. Copies may be ordered from the Publisher at admin@thematrixcc.co.za or at PO Box 1737, Port Elizabeth 6000, at a cost of R650 per copy.

Copies can also be collected from Kathy Munto at her office at Wits University, School of Architecture, or by making a personal arrangement.

Franco Frescura

Professor and Honorary Research Associate, University of KwaZulu-Natal. He is currently engaged in the documentation of the historical built environment of Durban, including aspects of its oral history and material culture.

Review published on The Heritage Portal with kind permission from the reviewer. Originally published in ArchSA, the Journal of the South African Institute of Architects.