Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The gavel is poised to fall on the sale of 29 ordinary objects: including a handmade key, a book, a pair of sunglasses and an ID. Yet their sale raises an extraordinary question: when does a revered leader’s legacy become so central to a nation’s identity that it can no longer be treated as private property? The impending auction of 29 of Mandela’s belongings, sanctioned by the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA), exposes the fragile line between individual rights and collective memory. It also reveals the limits of South Africa’s current heritage framework when confronted with privately held objects of exceptional national significance.

The case, pitting the state against auctioneers and involving a divided Mandela family, raises profound questions about the reach of heritage law, the evidentiary burdens placed on public institutions and how a nation honours its most revered figures.

What the Court Actually Decided – Majority vs Minority Judgment

The SCA agreed that Mandela’s belongings are historically significant. But the case hinged on whether SAHRA had followed the correct legal steps and provided sufficient evidence to request urgent judicial intervention.

The court held that SAHRA had not demonstrated, item by item, why each object qualified as a “heritage object” under the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA). Makaziwe Mandela, Mandela’s eldest daughter and Christo Brand, Mandela’s former prison warden, submitted affidavits explaining why the items are private property. On this basis, the court concluded that SAHRA had not made out a sufficient case for an interdict.

The SCA judgment does not formally recognise any of Nelson Mandela’s belongings as heritage objects. In summarising the High Court’s reasoning, the court noted that, arguably, a copy of the Constitution signed by Mandela could be regarded as symbolically significant because of what it represents about reconciliation and nation-building.

The majority bench emphasised that not every item Mandela owned automatically counts as protected heritage. South African courts, long respectful of private property, are hesitant to intervene unless the law’s formal procedures are clearly followed.

SAHRA relied on its 6 December 2002 declaration under section 32 of the NHRA, reinforced by a further declaration in April 2019, identifying objects linked to significant historical figures as categories of heritage objects. The majority judgment acknowledged these but held they did not replace the need for item-specific identification and motivation.

Importantly, the judgment was not unanimous. Justice T.V. Norman, in a minority judgment, argued that SAHRA’s reliance on the NHRA and its standing declarations should have sufficed for interim protection. Requiring itemised classification before intervention, she warned, risks undermining the preventative purpose of the legislation, especially when privately owned objects appear only when about to be sold. Norman’s reasoning focuses on the significance of the objects rather than formalities, especially those closely tied to Mandela’s historic legacy.

The majority judgment sidestepped a substantive determination of whether personal artefacts connected to the making of South Africa’s democracy merit heritage protection, leaving that broader question unresolved.

Supreme Court of Appeal (Wikipedia)

A Contested Family Landscape

The legal dispute is further complicated by differing perspectives within Mandela’s family. Makaziwe Mandela has argued that the case confirms the family’s authority to determine the fate of his belongings, including using auction proceeds to fund a memorial garden and museum in Qunu, Mandela’s birthplace.

After being approached by Makaziwe Mandela, Christo Brand donated two items in his possession toward the memorial garden, demonstrating a contribution to a public commemorative initiative. Several of Mandela’s grandchildren, however, oppose the auction, asserting that the items are part of South Africa’s shared history rather than ordinary private assets.

A memorial garden in Qunu could be greatly enriched by the artefacts themselves. Displayed in a heritage-conscious setting within or adjacent to the garden, these objects would allow visitors to engage directly with Mandela’s life and legacy, transforming the garden into a living museum of memory. In this way, the garden becomes more than symbolic; it actively preserves national memory. Here preservation and commemoration reinforce one another rather than compete.

Families undoubtedly hold intimate knowledge of a loved one’s values and wishes, yet when objects are deeply intertwined with national history, decisions about their fate resonate beyond the private sphere.

Qunu Landscape (Wikipedia)

Mandela’s Wishes and What He Could Not Have Foreseen

Mandela consistently resisted personal glorification and commercialisation of his legacy, emphasising collective struggle over individual acclaim. While he made provisions for his estate, he could not have anticipated a public auction of his personal effects in a global collectors’ market. The absence of explicit instructions does not amount to consent; it reflects the historical context in which he lived. This silence leaves unresolved ethical and legal questions about how such objects should be treated.

Heritage Value Versus Market Value

Without formal heritage designation, these objects carry little legal protection. Even items of profound historical significance can be overtaken by market forces, allowing artefacts closely tied to South Africa’s democratic founding to be treated as high-end collectibles, disconnected from their historical and cultural context.

The collection includes deeply symbolic artefacts tracing Mandela’s journey from prisoner to president: a handmade key to a Robben Island prison cell, his signed 1996 Constitution and his identification book marking post-apartheid citizenship. His signature shirts and iconic sunglasses capture the public persona that made him globally recognisable, while gifts from world leaders reflect his international stature.

Mandela in one of his signature shirts (Wikipedia)

South Africa already recognises the national value of former leaders’ effects. The personal papers, correspondence and belongings of heads of state - from the apartheid era to post-apartheid democracy, including Jan Smuts and Nelson Mandela - are overwhelmingly held in public institutions such as national archives, museums and universities. Taken together, these objects form a coherent, deeply personal archive of South Africa’s history. Their dispersal through sale risks severing them from the historical context that gives them meaning.

Estimates suggest the 29 items could realise several million rand, a substantial sum, yet arguably insufficient justification for the permanent loss of public access and national memory.

The Role and Limits of Heritage Law

South Africa’s legal heritage framework empowers SAHRA to identify heritage objects, restrict their sale or export and facilitate state acquisition. In this case, it attempted to engage with the auction house and owners before approaching the courts. Litigation was a response when negotiations failed.

The judgment highlights structural constraints: when courts require detailed, item-specific proof at an early stage, heritage law becomes reactive. The majority judgment entrenches this; the minority one exposes its limits.

Private Ownership and Monetisation of Proximity

Individuals connected to Mandela’s life have published memoirs or held memorabilia. The law treats them neutrally. The deeper issue is the absence of a coherent public framework to distinguish legitimate ownership from the gradual marketisation of national memory.

International and Global South Approaches to Protecting Heritage

Internationally, South Africa would not be acting unusually by asserting limits. The UK routinely blocks the export of culturally significant artefacts. France designates certain items as “trésors nationaux” or national treasures. In the United States, presidential papers and artefacts are subject to strict public custodianship regimes.

Across Asia, Africa and Latin America, states increasingly treat culturally significant objects as part of a shared national inheritance (or in heritage parlance, national patrimony), even when privately owned. Countries such as India, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Mexico and Peru have strengthened heritage protection through export controls, rights of first refusal and custodial regimes that balance private rights with collective responsibility.

These approaches are shaped by UNESCO norms emphasising prevention of illicit export, public access and protection of material - especially those linked to anti-colonial struggles. South Africa invokes these norms abroad but is inconsistent internally.

Mahatma Gandhi – A cautionary parallel

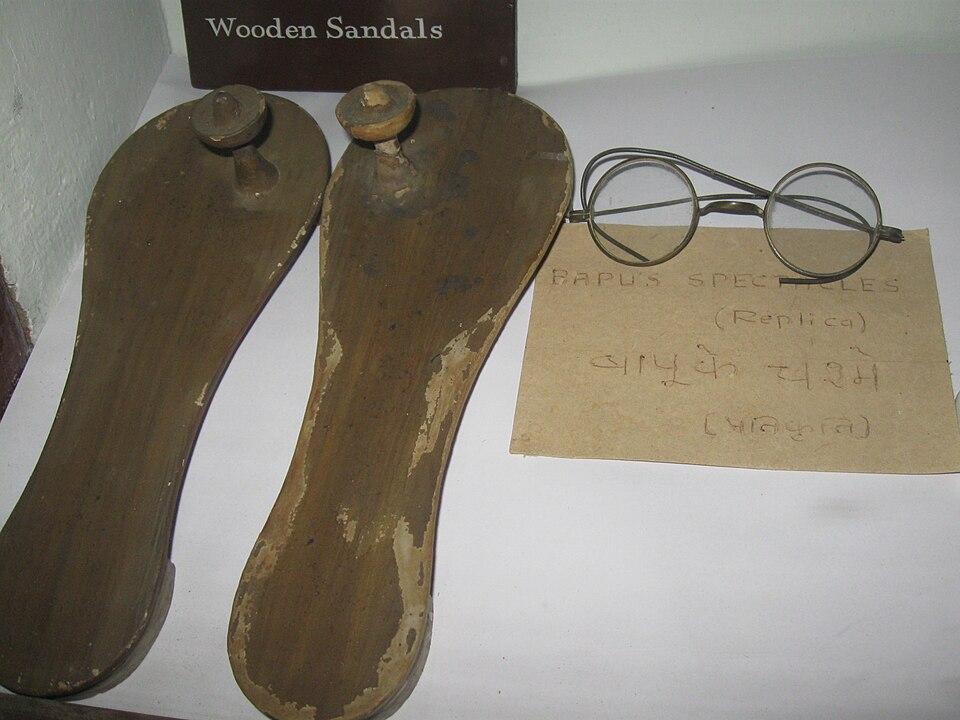

In 2009, Gandhi’s personal items including his glasses and sandals went up for auction in the US, but the Indian government said they belonged to the Navjivan Trust for public benefit and should not be sold.

Underlying these approaches is the public trust doctrine: certain resources are held for the nation, even when privately held. Mandela-related artefacts, by virtue of their exceptional significance, arguably fall into this category.

Gandhi's Sandals and Spectacles (Wikipedia)

Opportunity Cost

Spending public funds on SCA litigation carries a significant opportunity cost. Instead of going to court, these resources could have been used to negotiate the purchase of the items, set up custodial agreements or create a public–private heritage trust. Around the world, governments often use these proactive approaches instead of going to court, protecting heritage while keeping it accessible to the public. This remains a path that SAHRA could still pursue to safeguard Mandela’s belongings as national assets.

Without intervention, South Africans may one day encounter Mandela’s legacy not in Qunu or in a public archive, but behind museum glass overseas or in private collections accessible only by invitation or price. Objects that once bore witness to imprisonment and democratic birth risk becoming artefacts of exclusion: admired but no longer shared.

The Road Ahead

Although the SCA dismissed the case, the matter has not yet been legally exhausted – as an application for leave to appeal to the Constitutional Court remains available to SAHRA. An approach to the Constitutional Court is legally credible, grounded not in abstract hope but in existing judicial disagreement. Justice Norman’s minority judgment articulates a fundamentally different understanding of the NHRA. The Constitutional Court option rests on this existing judicial debate.

Constitutional Court (The Heritage Portal)

Fundraising, negotiated acquisition or shared custodianship remain possible avenues to secure Mandela’s artefacts for public benefit. The case also underscores the need for clearer protocols to identify and protect objects associated with historical figures before disputes arise.

A Cautionary Conclusion

This case is not a repudiation of Mandela’s legacy. It is a warning about how easily shared history slips through legal cracks when the law moves slower than markets. Justice Norman’s minority judgment shows South African heritage law is not inherently hostile to preservation, even with private ownership. Indeed, the judiciary itself is not unanimous on resolving such conflicts.

Mandela believed in institutions not because they were perfect, but because they could be made to serve the public good. Whether this episode becomes a turning point will depend on whether South Africa chooses to protect its shared history before it appears on an auction catalogue; rather than trying to retrieve it once the hammer has already fallen.

Saaliegah Zardad is a researcher and writer whose work focuses on heritage, cultural landscapes and post-apartheid spatial justice. Her research engages with heritage impact assessment processes and questions of intangible cultural heritage, living heritage, community meaning and public decision-making in relation to the Oude Molen Precinct and other redevelopment initiatives.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.