Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

On May Ist, 1989, Maggie Friedman and her partner David Webster, well known anti apartheid activist, parked their bakkie outside their home at 13 Eleanor St, Troyeville. As David walked to the back of the car to release their dogs, a shotgun blast from a passing car hit him in the chest. He fell to the pavement and died shortly afterwards. The two had been living together for four and a half years during the vicious eighties. With David, Maggie believed she had found the ideal future. Maggie agreed to talk because, she said, people need to remember their heroes. This is Maggie’s story, this is David’s story, this is their story:

David Webster House Troyeville (The Heritage Portal)

I met David through Bruce Murray, of the history department at Wits. I came down to Johannesburg in 79, I think it was, and Bruce was the only person I knew. David was one of his peers, his contemporaries at Wits, and it was through him that I met David. I came from Zimbabwe. David in fact came from Zambia; he was born on the Copperbelt. He finished his schooling in Zimbabwe. His parents moved down here, probably at the break up of Federation.

Did a common Zimbabwean experience draw us together? Yes I think it did. One of the things we really enjoyed was dancing. Although the music was universal, our style of dancing came from the same roots. It was one of the things we enjoyed very much. In those days at parties we always used to get together for a dance or two. It was so comfortable dancing with him because our styles were so similar; we understood each other so well.

In those days David was still with Glenda his wife. I saw them off and on. They lived in Crown Mines in a beautiful old cottage. I lived for about a year or so, on the other side of Crown Mines in one of those little brick railway houses.

David and I got together in ‘84, by which time he and Glenda had separated. We got together at a party and we arranged to play squash together. I was a very keen player. That was our first date, we played squash and I beat him. And I beat him regularly. He didn’t seem to mind. In fact he was quite proud of me. Then we set up squash as a regular event. The next time we played, he had an appointment to see Jennifer Ferguson at the Alba Hotel in Braamfontein. She was there, singing wonderful, sort of smokey blues with her little three-piece band. They were going to talk about her performing at a Jodac [Joburg Detainees Action Committee] function. Jodac arranged events to involve people who weren’t all that politically aware. It was one of the things David was particularly good at, knowing how to reach such people.

Our relationship developed quickly after that. David was very busy with things, very busy. Sometimes he might phone at ten at night and say he’d just finished his meeting and could he come round? His life was packed full; meetings, work for the DPSC and Jodac. But he also made trips out of the country. He went to Lusaka to meet the ANC, which in those days was quite something. He made trips to Swaziland which I think were involved with trying to get people in and out but he didn’t talk about it. When he went off on those trips there was always an overt purpose but I think there were other things he was doing as well.

I’d been here in Johannesburg for four years then and I was not active, distressed but not active. David in those days was working very hard for DPSC and Descom. I think David’s activism was sparked by the ‘suicide’ of Dr Neil Aggett in John Vorster Square. But I know that he had been politically influenced, primed perhaps, by a two year stint at Manchester University. I know he had been involved in that extended Wilson Rowntree strike in East London, where his mother lived.

Aggett was one of his neighbours at Crown Mines. It was around that incident that the Detainees’ Parents’ Support Committee [DPSC] was formed. Descom, the Detainees Support Committee was part of that: members round the country who visited parents, who tried to make contact with detainees, as far as they were able, defending detainees’ rights, keeping them in view – preventing their ‘disappearance.’ Then with my computer background, I got involved in a tedious job. We began compiling statistics from the registers of detainees they kept at police stations; so we knew who had been detained that week.

At that time David was staying in Cyrildene in Derrick Ave. He was staying in a flat above a shop. I was living in a garden cottage in Highlands North. In 1985 we moved to Troyeville. We moved into one of those cottages in Bellevue St. A delightful cottage, very small; a little patio with a huge view all around, very beautiful. So this was our first home together. But almost as soon as we moved in, at the beginning of ’86, David went off to Kosi Bay on a six month Sabbatical.

He’d worked a lot down there and he’d worked a lot in Mocambique. He’d done his original PhD. work in Mocambique. Glenda later said, that he’d joined the ANC when he was overseas and he’d agreed to work for them. It was suspected that the South African government was supplying Renamo through that border; running guns up. So it is quite possible that is why he chose to work there. When it came up later, that this may have been a reason for him being killed; it may have been a reason, but it certainly didn’t seem enough that he knew that arms were going back and forth, because quite a few people did know about that. People in the area were talking about it.

But one never knew what the reason was. And it’s still...one always thought, with the people you’re dealing with, they didn’t need a clear reason. If they had a grudge against somebody, that would be enough.

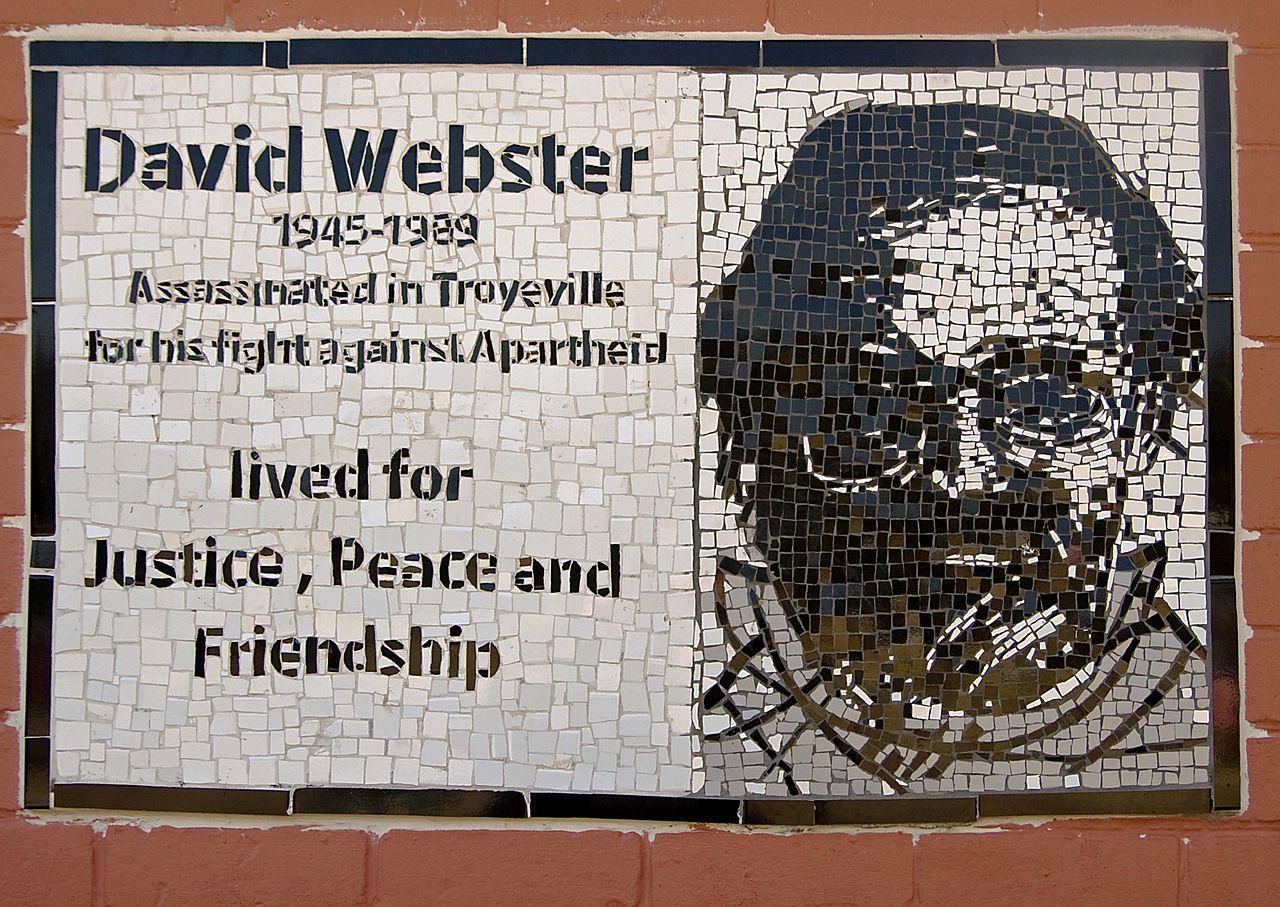

David Webster Mosaic (Derek Smith via Wikipedia)

I’m sure he did look out for those kinds of things and he did pass the information on. But more, I think, he was interested in what was happening there politically. And his anthropology, I think, was his main reason for choosing that area to work in, because it had a connection with the work he’d done before.

The community gave him a piece of land. At first he stayed in a tent. I used to go down to visit about every six weeks. It was indescribable, the heat and the humidity and the discomfort of living in a tent. Then he was given permission by the chief to build and he built a little reed house. He quickly established himself in the community. They really loved him. He was very good working with people. I think that was a very happy time for him. But it was also lonely for us both. He was very visible but he wasn’t the only white in the area. The CCB had a camp at Black Rock and the Natal Parks Board had an experimental station nearby. He tried to keep a low profile but he helped the community deal with Government’s efforts to move them.

When David returned from Kosi Bay we decided to buy a house in Troyeville. I started looking for a house. When we stayed in Bellevue St, we used to walk up to a lovely restaurant in Commissioner St, an Italian restaurant called Ragno D’Oro. On the way back we’d walk through Troyeville looking at all these charming little houses. We’d choose houses we really liked and no. 13 Eleanor St, was always my choice. I saw many houses. Some were unaffordable, some were unlivable. The estate agent phoned me one day and said I’ve got something I think you’ll like, and there it was, 13 Eleanor St. David loved it and in mid ‘86 we moved in, during those troubled times. When we moved he wouldn’t change his official address. He was very careful with things like that. He didn’t give out his home telephone number very easily.

13 Eleanor St (The Heritage Portal)

We moved into the house and one day during the first week, it was on my birthday, he came home and said he’d agreed to do something and he’s sorry about it, sorry it’s my birthday and will I agree to it? What he’d agreed to, was to take someone who was on the run, trying to avoid detention. She came and stayed with us for a few months. She was in quite a bad state; she’d been in hiding for some time. So she moved into our new house with us. She eventually left for overseas. We also had people from Kosi Bay who stayed with us. So we had a bit of a house full.

We didn’t often get the feeling that our phone was being tapped but I do remember when our guest was leaving; she devised this elaborate plan, she was dressed as a nun, to fly to Namibia and then to London. At two on the morning she was going, there was a call on the phone and there was nobody there – a sure sign of the Security Police. So with her in her habit, we all got into the car and we went and sat in David’s office at Wits for the rest of the night. We put her on the plane at six.

Wits Great Hall (The Heritage Portal)

When I first met David, he was very involved with Helen Joseph and he used to visit her often. Helen really loved David. He was terribly caring of her. He found Abby, the fat, slobby Labrador, for her. David used to walk Abby and through that he saw a lot of Helen. Helen went away a lot and David looked after her house. She fed the neighborhood cats. David found her a pair of kittens once. One of them was run over in the street the next week. I have this memory of Helen walking up and down Fanny Ave, in Norwood in her dressing gown looking for the lost kitten.

I occasionally stayed in Helen’s house. There were these constant ‘silent phone calls’ in the middle of the night, pure harassment. I stayed once when David went down to the Eastern Cape, I think it was for the Cradock Four where Helen spoke at the funeral. I think David spoke as well. The UDF had hired busses to take people down. As they entered Joburg, the two busses were escorted by the security police directly to John Vorster Square where all the people were processed.

Cradock Four Memorial (The Heritage Portal)

The relationship with Helen was a big part of David’s life. When David was killed she was already very frail. She was in hospital. It was very terrible for her. Helen was accepting of me but I think it was quite difficult for her. I wasn’t who she would have chosen as a daughter-in-law. She saw David as a son; she had no children of her own. I think she saw David’s partner as a sort of daughter-in-law. But she was kind to me and tolerant of me. She was intensely loyal and I think that’s what made her behave so graciously towards me.

They had their little tiffs and coolings of the relationship. David and Helen argued about the Five Freedoms Forum which David co-founded. It was an organization aimed primarily at making whites more politically aware. Helen wasn’t very supportive of the strategy. She was angry that David was putting his energy there; she thought that whites were a waste of time.

We lived in Eleanor St, for three and a half years before David was killed. It was a very busy time. There was so much going on, meetings all the time, all these different organizations: Five Freedoms, Jodac, Descom, there was DPSC, there was the UDF itself, all these things that David was involved in. It was full of intrigue; people turning up at our door needing to spend nights. People coming to Joburg to attend meetings; people in and out of the house all the time. As for being watched, well not really. One was always cautious. Every now and then we’d get a feeling of being followed from a particular meeting. But on that weekend, David was killed on a Monday, I took a friend to the airport and it was the first time I really got a sense of being followed.

I was involved in DPSC. It was banned and then we set up the Human Rights Commission which continued with the collection and publication of statistics; how many people had been detained, how many people had died in detention, how many had been assassinated. Those figures caught the attention of the press. When David was killed he’d actually been writing about it.

Thinking back, I don’t know how he found the time for all these things. Probably one of the ways was to neglect his academic work. I know Wits gave him uphill for not producing work from his Kosi Bay sabbatical. He’d been given money for that. Eventually he jolly well had to sit down and do it or give the money back, and he did some good work.

David was able to relate to many people and on many different levels. He had that extraordinary ability to make people feel special, even if he’d only given them a tiny bit of time. There was this intense political activity but David was involved with a whole lot of other things at the same time. He was always going to listen to nice music. He knew a lot of musicians and he made time to spend with them. He was interested in soccer and he was a member of the Orlando Pirates Soccer Club. Even though he’d had a weekend of meetings, he had time for music and soccer and other friends, doing other sorts of things. We would go to Jabulani Amphitheatre and listen to local music festivals. He helped the African Jazz pioneers get going again; these lovely old gentlemen swinging with their saxophones. He was very supportive of Johnny Clegg, his colleague in the Anthropology Department. Mango Groove was starting up. He’d listen to that sort of music as well. His energy was overwhelming, a tidal wave of activity and people. In each area of activity there was a huge range of people that he knew. It was and remains very nice for me, because many of those people have become friends of mine; they really broadened me. But despite all that energy, we shared a great intimacy.

Jabulani Theatre (Lucille Davie)

I think I gave him a very sort of safe place outside all the different things he was involved in. He was pleased to be with someone who wasn’t involved with all the other things and all the history. Also he was quite jealous, possessive and that’s why he was pleased that I was outside of all the other things. He was bright and outgoing, that was the public aspect to him, but there was also a darker, private aspect that was very well hidden.

Regarding his death, I was thinking that it wasn’t beyond possibility that he had some sort of warning that he was a target. There was another David Webster around and there are other Websters around, and it turned up in the investigations that they had been getting threatening phone calls. David certainly never spoke about getting phone calls, but I can’t believe that our number was unknown to them... I don’t know. Otherwise it came completely unexpected. David wasn’t an obvious target. He didn’t seem to be living in fear of anything other than the normal sort of harassment. He’d never been detained but he was obviously well known to them. I think that we all had a feeling that he was a bit untouchable; one of the establishment, and so visible, and a generation older than most of the activists. And he always made a point of wearing a collar and tie on public occasions, always respectable. Also he tried to reach out to people in business and the white establishment in an attempt to bring them in. He was respected in the business establishment. He was often asked for comments by BBC World and Radio 702.

But I’m not sure how far his activities extended. I’m not sure how threatening he was, how he was perceived? We know there was an assassination list of high profile people. He certainly fitted that description. There might have been a clandestine aspect which I didn’t know about and still don’t. I don’t think the people who made out the hit lists gave much thought to the consequences or the gains to be made out of assassinating people like David. In his case, there were extensive losses for the other side.

We usually went running on weekends with a group. Because it was raining that Sunday we ran on Monday morning. We’d decided to spend the day together and that I’d bunk my Human Rights Commission meeting. We used to run round Crown Mines which was very undeveloped; through the Gum plantations and round Ormonde Golf Course. We took our dogs with us. So on the Monday, it was just David and I. Afterwards we went off to get some plants and buy some bread in Hillbrow. When we got home we parked outside our house. David got out to let the dogs out and I was getting out on my side when I heard a car coming down quite fast and I heard something, which I thought was a backfire. And then I saw David was stumbling; it seemed like it was all happening very much in slow motion. I didn’t immediately realize what had happened at all, and he said ‘I’ve been shot with a shotgun, call an ambulance.’ And then I realized he was clutching his chest and then he fell onto the pavement and.... I think he just bled to death. I shouted for help. It seemed to me that it took a long, long time for anybody to come out and help. Someone tried to resuscitate him. Eventually paramedics arrived but he died within minutes of them getting there. There was no possibility of saving him. He was shot right through the chest.

I called my meeting then, the meeting I should have attended, because I knew Max Coleman, a key person in the network would be there. It was clear that it was an assassination, it was a targeted thing and it wasn’t my private thing at all. From that moment, I realized that I had to give it to people to do something with. I felt there was no other thing to do with it; it had to be like that. I had to relinquish it. From then on my private grief interleaved with the public stuff. One of the things about grief is that sharing is so helpful, there were so many people David knew, close, close friends who were all grieving very sorely. There was that support and that allowed some of my private grief as well. What was difficult was that there was no closure to it because of all the things that subsequently came out. There was no way it could ever be in the back of my mind.

For ten years it just went on and on and on. The inquest and the commissions were all so unsatisfactory that instead of bringing a sense of closure they brought a sense of real frustration. And they were all so public, which was very difficult. But I did have a sense of huge obligation not to let it rest or go out of the public eye. I thought it was necessary to be there until there was some sort of a breakthrough. We now know that Ferdi Barnard was definitely the person who shot David. He confessed in court. But previously he’d gone through an inquest when he’d denied all knowledge of it. Barnard, tried to contact me from jail, but I decided I didn’t want to meet him; I didn’t want to be used. I suggested he speak to the prison authorities. Nothing more has come of it.

There was the Harms Commission as well, which found that there was no such thing as hit squads. I think it’s a fact that Calla Botha was in the car with Barnard and maybe someone else as well but will they ever be punished? We’re still waiting for the whole truth to come out but my feeling is that with all the things that have gone undetected and unprosecuted, I‘m lucky that we’ve got some sort of justice out of it, that someone’s been prosecuted. So many people have not paid. There’s been no justice for those terrible train massacres and all those other terrible things that happened.

David’s funeral was used to say there’s nothing they can do now! It was a show of power. It was a significant funeral. They wanted to ban it. They had been banning funerals – you could only have twenty people, you could only have families, you could only have it on a weekday, - there were so many restrictions on funerals. They tried to put a restriction on David’s funeral. I think diplomatic pressure was put on them to allow the funeral to be open. So many people were mobilized for the funeral. David was part of so many groups, political, academic. musical, sporting. For instance, Orlando Pirates participated officially; they carried their flag in the procession. Johnny Clegg spoke at his funeral, Jennifer Ferguson played, and Amos Ngubani from Kosi Bay made a speech.

David wasn’t religious, I wasn’t religious, but we realized that people would want a proper burial. It was important to have something public, something big, to say, look at what is happening here. The funeral was held at St Mary’s Cathedral. We were looking for a big venue and initially we approached the Catholic Cathedral in Saratoga Ave but they weren’t interested. The Anglicans were very glad to have it. St Mary’s was packed and we buried him at West Park Cemetery. The procession was huge, very long. There were Casspirs posted all along the route. The youngsters in the funeral procession were taunting them. People were shouting slogans and waving banners.

The police had obviously been given strict instructions that they were not to do anything. They stood sullenly by their vehicles. The procession went out of town then went through the suburbs, Emmarentia, Greenside, on the way to the cemetery. These suburban families came out of their houses in absolute amazement to see this huge procession of chanting people. People toyi toyied along the whole route. I was in a car with my family but for some of the way I felt I had to get out of the car and just go along with the crowds along the street. In some ways it was wonderful, you felt as if you’d managed to break open the doors of things. It felt like it was a bit of a turn around point. Things had turned around already but we didn’t realize the extent of it. Nine months later, Mandela was released.

One of my saddest times was when Mandela came out of prison. I felt it was so unfair that David had missed it. So close! It was heart wrenching for me to celebrate that without him. And the other dreadful occasion was when Chris Hani died. It was like the same thing all over again. That was really terrible.

While David’s death was awful for me, it built me a lot. I am a very shy and reserved person. To be in such a public spot was really difficult. As well as all the grief and the feeling that my world had fallen apart, I had to get through it and I had to go for the thing of getting justice for David. It changed me, it built me, and it was somehow a richly rewarding thing to be made to go through, to go through all these things. The other thing that happened for me, and also very difficult, was that people somehow made me take on David’s role. People who would have gone to David with things now came to me with things. They asked me for the insights that they would have expected from David. I think this happens a lot when a partner dies. The people around expect them to be living in you somehow. I used to deal with that by putting myself in David’s place. I’d ask myself, now how would David respond to this? I think that was the way I became someone else. [laughs!] Since then I’ve moved on a lot, but that gave me the ability to change my life. I think in some ways, this is where the children came into it.

When David died, I was at the end of my thirties. I think it’s a time of change for most people. I mean, your young life is over. You think about yourself and what you want for the rest of your life. With David I was looking forward with such pleasure to the rest of my life. We were so contented together, and I got from the relationship exactly what I wanted from it. With David gone I had to either sink, or build the rest of my life.

I had this image that I would have children, although it was so late in life for doing that.

I investigated ways of having children in those circumstances. I was encouraged by my Doctor to go the adoption route. Still today, it’s not easy to adopt a child. It was in 1991, eighteen months after David died that I set out on this course of action. It was illegal at that time to adopt across the colour line but there was a feeling of shift and change. I went to Social Welfare. They were thinking about changing the way things were. The cross race adoption regulations were lifted in July, 1991 and I got Leo in September, 1991.

It was funny going through that, because for the first half of the year they stalled me, but they never said no. When the regulations had been lifted, I gave them a few weeks then I phoned them and said, ‘I’ve heard that the regulations have been lifted so tell me if you’re not going to give me a baby and I‘ll go somewhere else.’ And the next day they phoned me up to come in and then they said, we have a baby and it was that quick. I took him home a week later.

The memorial happened in 1999. I was talking with Lael Bethlehem. We were talking about it being ten years and we must do something. Lael knew this mosaic artist, Ilse Pohl. She had this idea of making it somewhere public and we decided on the wall of 13 Eleanor St. So we got together a little committee again and we raised money. Ilse was very excited. We talked about ideas; the things David had been interested in, music, politics, football, and how to incorporate this into the mosaic. Most of those things can be seen in the mosaic. I liked Ilse’s idea of recording the images of the children’s hands, giving an image of continuity, of moving into the future. The main thing was that it should be accessible and feature the community in which he’d lived, a live memorial rather than being somewhere out of the public eye. It was lovely to live with and very hard to leave for our new house, but the people who bought the house are looking after it.

The Mosaic (The Heritage Portal)

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.