Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6. Please note that the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust transformed into the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation in 2012.

On a Saturday afternoon, an earnest and expectant crowd surrounds a woman in old Brixton Cemetery. They mentally recoil from smashed and overturned memorials, headstones and grave markers in this no longer used, historic gathering place for Johannesburg’s dead. The late summer afternoon sky is piled with thunderheads, but for the moment it’s hot, sunny and still; the wind presaging a highveld storm has not yet stirred. This short, blonde woman, knowledgeable and energetic, stands talking before a family grave. But her audience does not comprise mourners, rather they are visitors enjoying a tour of the graveyard, organized by the Parktown & Westcliff Heritage Trust. [P&W H T]

A scene from Brixton Cemetery (Kathy Munro)

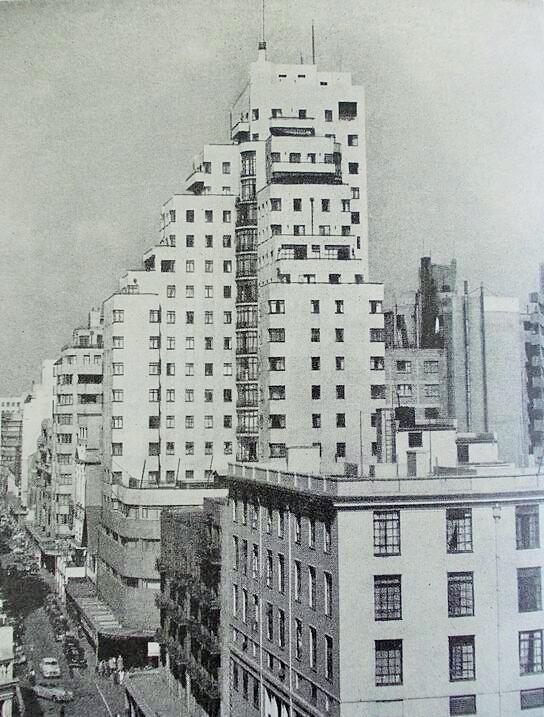

Interred in this family plot are Randlord Lionel Phillips, his wife Florrie who founded the Johannesburg Art Gallery and their son Frank who managed the family farm in Magoebaskloof. Later she tells her listeners about Norman Anstey who ran his department store in the Art Deco building in centre city which bears his name. She tells us about hanged Taffy Long who, many claimed at the time, was innocent of the murder of a shopkeeper during the 1922 Rand rebellion. Here we acknowledge the last resting place of Mary Fitzgerald’s beloved Archie Crawford taken early by typhoid and alongside whom she too now rests. The dynamic woman talking to those fascinated by Johannesburg tales, is Flo Bird, who founded, and has been Chairman of the Trust since its inception in 1986. Indeed, it would be difficult not to mention the Trust and Flo Bird in the same breath. On other afternoons her audience might be listening to her descriptions of Herbert Baker designed Parktown houses, or a description of Indian life in and around Diagonal St, or the miners’ suburban world of early Jeppestown. During heritage Week in September each year, P&W H T guides offer visitors a comprehensive immersion in historic Johannesburg.

Johannesburg Art Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

Old photo of Ansteys

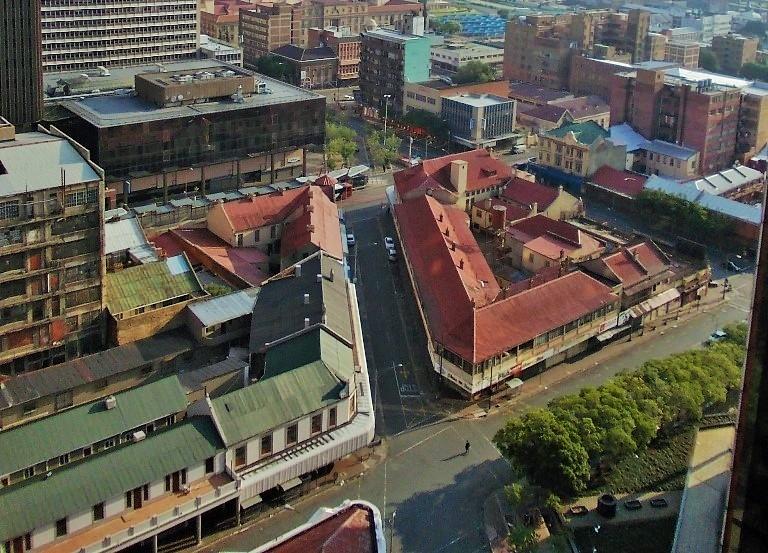

A few of the buildings of Diagonal Street from above (The Heritage Portal)

Not only is Flo Bird an ‘Encyclopaedia Johannesburgiana’ but she is a one woman guerilla force. This child of Johannesburg Pioneers, unbidden except for her love for the city, her conscience and a directed sense of outrage, has for more than thirty years, fought the buccaneers manning the pirate ships, ‘local government’ and ‘development’ in their wholesale plunder of her suburb and her city. Future generations might be grateful for Flo Bird’s magnificent anger.

She and her husband live in the 1903, Parktown West house in which she was born and which the couple later bought from her parents. Her three sons grew up in the house. She’s so much the ‘local girl,’ having been educated at Parkview Junior and Parktown Girls’ High Schools. She studied History at Wits and prepared herself to teach with a high school teacher’s diploma. She taught juniors for awhile, then the family arrived and while diligently acting the full time mother role, her life assumed an unexpected direction. She says, ‘The residents of Parktown West were alerted to the danger of non residential users moving into our suburb to escape the planned motorway. Six of us canvassed the neighbourhood and we held the inaugural meeting of the Parktown Association on a freezing cold night in July 1973. Later I was asked to join the protest against the demolition of old Parktown.

‘In the seventies,’ she says, remembering the start of her activities, in effect her life’s work, to save historic Johannesburg, ‘the city was doing very well; much building going on, expanding at a hell of a rate and then, a knell of doom sounded for Parktown. At that time there was expropriation for the [Johannesburg] hospital, about twenty three properties. Then there were the expropriations for the park [Pieter Roos Park] and more for the College of Education. [now Wits Education Campus] So effectively, Provincial Government and the City Council ripped the guts out of Parktown. Of course the park was eyewash, they wanted that for the freeway but we didn’t realize it at the time. There was this huge area that suddenly went dead. It wasn’t immediately demolished. As the properties were sold they became communes, we even had a few brothels, they fell into disrepair, the gardens went; there was a horrible sense of decline. All those great houses disappeared, one was burnt as a demonstration; it was a dreadful period. There were protests. They formed a Parktown Property Owners Association and I don’t know why, but they didn’t win any battles.

Charlotte Maxeke (Johannesburg) Hospital (The Heritage Portal)

‘At first it never occurred to us that we might be in danger. It was something happening on the other side of Jan Smuts. But suddenly, we in Parktown West realized what was coming our way with the M6 [proposed east west motorway through Parktown]. It was a wake up call! The whole atmosphere of the times… The council was all very secretive. It was run by the technocrats. The City Engineer was king; he even earned more than the Town Clerk, the most senior Council official. When I found that out I nearly died laughing, but that was true. And the Councillors, if the City Engineer said something, it went; if it was a road, in it went! We found that extraordinary, as ordinary people it seemed quite the wrong way round: you don’t design cities in order to move motor cars. But the City Engineer was a man of the motor car. [Incidentally all our city engineers went to Parktown Boys High.] We were shattered that the engineers could think like that. All their training, their ideas came from America. They saw Johannesburg as some Mid Western town dominated by freeways. Unlike the British, they believed that anything could be knocked down to make way for a freeway. South Africans were slaves to whatever the American people were being told at that time. There was a total lack of independent thought. We look back on it now and can hardly believe it. Then, no one thought of protesting. The Parktown Association bore the brunt of uncovering the council’s freeway plans for years. We lodged objections to every application for non-residential rights, and quite alone we opposed ad hoc rezonings.

‘The British believed that their old towns and cities were valuable and shouldn’t fall prey to roadmakers. We believed that Parktown was a very valuable part of the city. We mounted protests and the plans for the M6 were scrapped, but actually, it was the recession of the eighties that saved us. They couldn’t afford a freeway and they scaled the whole thing down into arterial roads. It was a matter of economics, it had nothing to do with common sense. That was the time when sanctions were beginning to bite.

‘My feeling for heritage came from my Dad. My grandmother was born in Johannesburg in 1890, when the town was four years old. She married in 1908. My father had very strong feelings for old Joburg and I was Daddy’s child and he used to take me walking in town and he told me about the rocks. He was a geologist, he just loved the rocks and the stones and the strata that lay exposed all over. One of our favourite places was what was called the Africana Museum, upstairs in the Library building, where the rocks were all laid out in the geology section.

Johannesburg Public Library from above (The Heritage Portal)

‘And he loved old buildings like Corner House. We used to have a thing called Paddy’s Market, he loved going there. It sold hardware, an open air thing, between Bree and Jeppe near the Phoenix restaurant. There were little old shopkeepers he knew around there; of course that’s all gone. He loved the University of the Witwatersrand, that’s where he graduated. And he loved Vrededorp, where he was a little boy. His parents’ house has actually gone but during the 1922 Strike they all huddled in the cellar because they were being shelled from the Rand Showground area. I suppose those things weren’t all that old but he enjoyed things that had a story and a history to them. I don’t think he had much of an eye for architecture, but he was tremendously proud of the bullet holes in Cottesloe School where he was a scholar.

Old photo of Corner House (Views of Johannesburg and Suburbs)

‘There were things like the Art Gallery. We always went to the Art Gallery; we had very little money, so we did things like that, the Zoo was free in those days. In the Art gallery we were allowed to choose our favourite picture when we had finished looking around. Now it wasn’t something you were taking away, but somehow it mattered tremendously to choose your favourite thing. So we all got to know our favourites. So Johannesburg to me, as I grew up, Johannesburg was an immensely exciting environment. My dad made it exciting.

‘My version of Johannesburg history came largely from rocks and gold and also from a working class point of view. My father’s dad was an old member of the Communist Party although he made money later. We were brought up on the belief that everybody had these rights. There was always a political consciousness; my father was terrifically anti Nat. Working class history was important, which I don’t think most children were ever introduced to. I was shattered when I found out how ninety per cent of people including my own tour guides, supported the capitalists against the miners in the 1922 strike. It always shocks me because it never dawned on me that capitalists could have been right. The way I was brought up, you know, the workers were being fired on by these beastly exploiters.’

Market Square Fordsburg during the Rand Revolt (Through the Red Revolt on the Rand)

Intrigued with an earlier statement, I pull Flo Bird back to the Art Gallery, one of my own favourite places. ‘What was your favourite picture?’ I ask. ‘My favourite was always a sculpture, Miss Fairfax [Rodin’s alabaster bust of Beatrice, the famous beauty] and it never changed. Every time I went to the gallery, Miss Fairfax was the one I visited. Then there was a picture, the one painting I liked, with a skull in it, very beautifully painted, and a box and a bag of money on a shelf. You didn’t know what it was about. In fact my father was very cross with me for liking that one. My brother liked a terribly sentimental one and my sister liked the Impressionists. But for me Miss Fairfax and another sculpture, The Slave, those were the ones that impressed me. My father ranted against slavery, he was bitterly anti racist. I remember weeping buckets when I read Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I’d been taught that slavery was dreadful and in my young mind it was an easy jump from slavery to apartheid.’

Miss Fairfax bust in the Johannesburg Art Gallery

I apologise for the digression and we return to seventies Johannesburg, and the beginnings of Flo Bird’s activism. “Who was the enemy?’ I ask. She replies, ‘The first great enemy was definitely the Council. Partly because of the roads and partly because of their planning, in fact, no plan was ever revealed. We can look back on it now and realize that the two were linked. Their plan for Parktown was a well kept secret. I think they were trying to hide their intention concerning the motorway. They wanted to buy the properties at the most reasonable rate. I attended the first hearing for consent use. Councillor Alf Widman warned us that nothing of our discussions could be revealed to the press. Today of course the Constitution, protecting the right to access to information, has done away with all that nonsense.

‘Then came the property developers. Because there was no plan, they just went out and grabbed as much as they could get. The house owners who couldn’t sell their properties to the developers, those who were done down, were those who stood on the proposed freeway route, so somebody must have known about the plan. We wanted a plan to set out appropriate limits. At that point we were quite unsophisticated. We thought that instead of allowing office blocks Council should have protected the old houses and their big gardens. They should have granted them high density rights or office rights in the old buildings and not lost the very beautiful character of Parktown. They could have kept some of the old houses for student residences instead of bulldozing everything for the College of Education, for those horrible high rises. We were shattered at that wholesale demolition and destruction. We felt very bitter about that but the battle was completely lost when the Administrator in Pretoria eventually granted business rights. That was the end of old Parktown as we knew it.

One of the demolished homes was Hohenheim (Lost Johannesburg)

‘Most but not all developers were uncaring of the suburb. Hunt, Leuchars and Hepburn, they were fantastic; they kept the old house, built a new building and put all their parking underground. The other one was 22 Girton Rd, where all the parking was underground. The Council missed so many opportunities. They should have forced a residential component upon the office developments, like they’ve done recently at Melrose Arch. Wits and JCE academic staff, hospital staff, all those hundreds and hundreds of people, could all have lived within walking distance of their workplaces. It became another dead-by-night commercial area. St George’s Church nearly closed, there were fears that Parktown Boys might close. The Council didn’t get involved. They just waited. If a developer came up with an idea they just accepted it.

St George's Church, Parktown (The Heritage Portal)

‘But things do change. Then, we were very unsophisticated. We’ve become far more environmentally aware. Now, if a developer comes up with a project, we sit down, go through it very carefully to make sure for instance that the paving is permeable so that there isn’t too much water run off. If there’s an old building we look at how they’re going to build next to it. In those days we were so grateful if someone wanted to keep an old building, we didn’t care what went up next to it. Not that we had a say then of course. Today, automatically, we require that the site plan be submitted to us before any building takes place.

‘Why do I fight?’ ‘Basically because I get angry,’ she replies. ‘Every now and again I think I’ll be civilized. And then they annoy me again. What really made me so angry in the beginning were the Council’s lies. They lied to us about the freeway and they kept lying to us for another twenty years. That kept me boiling with rage. I’m driven by rage. When I get angry I act! Other people will sit down and say, what a terrible idea; like the Zoo tower for instance. I can’t understand that sort of behaviour. They complain but do nothing, but I fight. I have to admit it, anger makes me active. For me, if you don’t do anything, for goodness sake don’t grumble about it later!

‘I don’t remember being that angry when I was young. I was never an angry young woman in a general sense. I was driven to anger by the lies, the denials. No, they said, there’s no such thing as the M6. Councillor Oberholzer and I battled it out in the newspapers for years. When the Progressives came in I discovered that at first there was no difference, they were also secretive. But eventually, Paul Asherson asked us, “what do you want?” We said, “if that land, that blighted section through Parktown is not earmarked for a motorway, what are you holding it for? Sell it.” And they did; first time somebody did the honest thing.’

The View survived the onslaught on Parktown (The Heritage Portal)

Hazeldene Hall also survived (The Heritage Portal)

My next question to Flo Bird is, ‘How did you fight? Did you train yourself to be a town planner, to be a lawyer?’ She responds, ‘That’s a bit of an exaggeration, I spent a lot of time, not in court, but in Township Board hearings. In the early days we usually had lawyers against us, nowadays the developers just bring a town planner. One of the first applications I fought, I couldn’t believe it, they had senior counsel, junior counsel, instructing attorneys, specialist attorneys and town planners. There was a team like that on their side and then there was us, me, a housewife and a colleague. Gradually that changed. I don’t quite know why that happened. Probably, the Township Board became impatient with lawyers. Lawyers are paid by the hour, so they’d spin it out for days, bringing up all sorts of irrelevancies while we just wanted to get on with the case. On that early occasion I think I performed abysmally, but I did learn that I could not go in without having covered certain of the basics. A lawyer can pontificate as much as he likes but if you have checked all the documentation and if it isn’t all there, then the lawyer’s in trouble. So every now and again you have a joyous moment when you find that they haven’t got the bondholder’s consent or one of these other little things.

‘I learnt that I had to be a lot more precise. Although lawyers can bore you to tears, they know the law, so even with my impatient brain, I eventually learnt to evaluate issues in legal terms. One of my early mistakes was to ask someone to present evidence before the board. Without any legal training I found that I couldn’t protect that person. But I later learned that you don’t have to give evidence, you let them make a submission. Then the other side can’t bully as much. We found that the Township Board itself gradually improved; they won’t allow developers to go on bullying those who oppose them. How many hearings have I attended? Remember I’ve been doing this for thirty something years. I guess I’ve dealt with round about a hundred hearings. Come and see my office.’

It looks like an old fashioned lawyer’s archive, stacked to overflowing, on shelves, chairs and desks with folders and papers – demobbed foot soldiers from the thirty years war.

‘What were the origins of the P&W H T? In laying down our battle lines, for the Parktown Residents Association, one of our resolutions was to retain as much of the heritage as possible, that’s how the P&W H T started, although the Westcliff part happened later. At first it was just a sub committee of the Association and later we established the separate Trust in 1986 under my chairmanship, with a small membership that’s grown over the years. And yes, I’ve been chairman of the Trust from that date to this.

‘As for our walks, we learnt, while trying to save Markhams Building in Eloff St, that people, the public, will only fight for things they know, so that’s when we started the Heritage Weekend walks through Parktown. The first were around the Jubilee Rd, Wits Education Campus, area. That first year, that was ‘82, we only had two guides, we must have taken hundreds each, but our walks programme was very successful. The next year was equally successful; fortunately we had a few more guides by then. Later we did the Herbert Baker houses. There was a huge demand. At first we didn’t charge. Ridiculous, said our sponsors. So we charged two rand, then five, now we charge twenty rand. We do make money, but I ask you, what can one do for 20 rand in Johannesburg today? Even going to the Zoo costs more than that.

Old photo of Markhams (Views of Johannesburg and Suburbs)

‘The Trust has grown, showing a current membership of some 400 members. We run our own tour guide training programme, or at least we did until the regulations became so stringent and so expensive. After all we’re all volunteers. Who can afford a two thousand rand training programme? We publish low cost pamphlets on Johannesburg history, largely as an answer to coffee table books which offer limited availability. We operate a research centre situated in Parktown Convent where we hold files on every property in Parktown, on many in Westcliff and heritage data covering every area through which we run tours. We charge R250 for access to our files and we find that people are not that keen to spend that sort of money. If they were to use a recognised cultural historian they’d be paying five to six hundred rand an hour. At the moment I doubt whether anyone knows as much as we do about Langlaagte and certain other areas of the city, Jeppestown and Fordsburg for instance. Our office is located in Northwards at the top of Oxford Rd, where our one full time employee organizes and advertises all our tours, obtains permission from house owners for our visits, deals with membership issues.’

Parktown Convent / Holy Family College (The Heritage Portal)

Flo Bird tells me that she seldom represents the Parktown Residents Association at hearings nowadays, it’s a task that has become just too onerous. Today most of her ‘watchdog’ activities are as the Trust Representative on the Joint Plans Committee for Parktown, Westcliff, and Parkview. ‘We sit and make a decision on the applications that come in,’ she tells me. ‘Quite often they might be building plans, they might be town planning applications. For instance like this tower thing at the Zoo. I picked up on that one, sent the notice out to everybody. Discussed it at the next meeting when we formulated a response.

‘Are you a statutory body? I ask with the concept of legitimacy in mind. ‘No!’ ‘How come then, do you get plans and applications referred to you? Is there any other similar body operating in the city?’ Flo Bird says, ‘There’s a Melville group but they don’t seem to be as successful. Johannesburg Council building inspectors usually refer the old buildings to us because local communities have rights under the Heritage Act. It seems that referring plans to us is just easier than getting involved with province. In fact it’s easier all round. Province tends to accept our comments, they’ve become dependant upon us to some degree. We stamp and sign the plans submitted.’

This does not explain why there are no other such bodies operating in Johannesburg, nor why the Melville group is not as successful as their Parktown counterparts. Perhaps Flo Bird’s smouldering presence on the Committee, waiting to ignite at the slightest infringement, ensures its continued effectiveness. She explains it differently: ‘It’s our duty. I don’t believe a community should expect somebody else to do all their work for them. For us, because of our early experience, planning is such a vital part of heritage. If Parktown and Westcliff can’t bloody well afford to look at their building plans, if we aren’t prepared to dedicate time and expertise, then how can we expect someone else to run around looking after our heritage for us?’

Flo Bird is steeped in heritage activities: ‘I was a member the Johannesburg 100 Committee which selected 100 sites and buildings to represent milestones in the city’s history. As chairman of the National Monuments Council’s Plans Committee we influenced developers to save rather than demolish buildings and to find ways of making them more viable. As a member of the Northern Areas Group of Residents we won the battle to conserve Johannesburg’s ridges. With others on ’Save Zoo Lake,’ we halted the dreadful proposal to turn it into a shopping mall. Most victories were not mine personally. I was not a lone crusader. There was a great deal of community support.

Several plaques that were part of the JHB 100 campaign (Kathy Munro)

“What about battles won and lost? We lost the battle for Arcadia [Stately home of Lionel and Florrie Phillips, later the Jewish Orphanage, now Hollard Insurance Headquarters]. Even though they’ve retained the house and certain ground surrounding, we didn’t want that, but we lost the rezoning [for business rights] battle. We went on appeal to the Townships Board and we lost. One of my first big fights was Sunnyside Park Hotel [where Alfred Lord Milner lived, post Anglo Boer War]. We lost all the property around it but we managed to get the front of the hotel declared a National Monument. I thought the rich Houghton residents were going to resist the rezoning but eventually they all sold out. I was bitter about that. I learnt than that it’s not easy to trust the rich. To the middle class, their house is their home, something worth keeping: to the rich, it’s just another asset. Here in middle class, Parktown West, people were offered huge sums for their properties. But there was a totally different attitude: not one of them sold. I’ve had some dreadful disappointments, like that petrol station in Empire Rd. It must be one of the ugliest developments in Johannesburg. It ranks alongside the Hospital. We had an avenue of Plane trees down Empire Rd. They promised us faithfully they’d keep the trees. They chopped them down.

Villa Arcadia (The Heritage Portal)

Sunnyside Park Hotel (The Heritage Portal)

Triumphs? ‘We beat Engen when they wanted to move onto this side of Jan Smuts. We stood there with posters. My older residents kept it going; stood there all day, every day for about ten days. It was in ’89, during the State of Emergency and the Black Sash told us how far apart we must stand. Afterwards, other developers said, we won’t come in if you’re going to do that to us. They realized what it would do to their image. Our next major victory was when Lombard wanted to erect five and seven storey blocks in a circle around Valley Rd and Jan Smuts. We had a public meeting. We were mandated to negotiate with the developer. We then suffered eighteen months of our own Kempton Park. I can fully understand how the negotiators felt after that. There were days when you were boiling with rage. Yes we got offices but we gained four new residences and they didn’t touch Valley Rd.

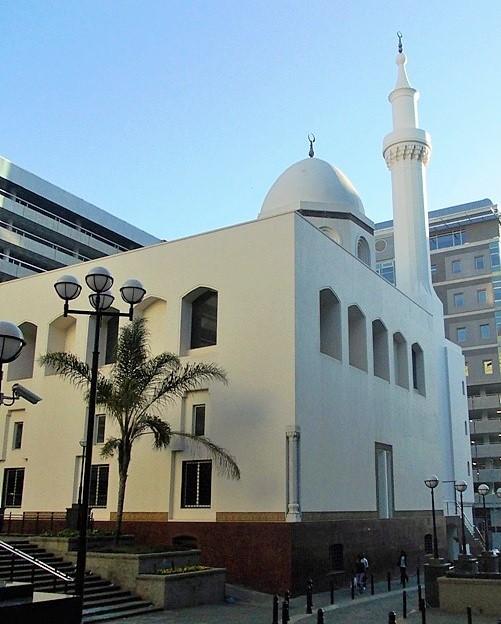

‘Diagonal St was my biggest fight. It was awkward politically. PW Botha was still in power. It was a scary time. Those Indians didn’t know whether they were going to be thrown out. We couldn’t appeal on behalf of the community, we had to concentrate on the historic value of the buildings. But we saved those two Victorian Buildings. And the Monuments Council, all those Broederbonders, declared the steeple of Father Huddlestone’s Christ the King Church in Triomf formerly Sophiatown, now Sophiatown again. That was quite an achievement. I was sad about the loss of the Kerk St Mosque, but I have to admit, I was wrong there. I love the new one, it’s a beautiful building. We lost the Colosseum [cinema] We won the Workers Hostel and the public toilet and the potato shed in Newtown. I suppose we’ve done quite a lot.

Church of Christ the King (The Heritage Portal)

Kerk Street Mosque (The Heritage Portal)

Old photo of the Colosseum (Cumming-George)

Workers' Museum (The Heritage Portal)

‘Why are Joburgers seemingly so indifferent to their city?’ I ask? Flo Bird comes back in a flash. ‘They’ve been brain washed into thinking their city and its history are insignificant. This was largely the work of the Nationalist regime which underplayed the contribution of the English speakers to such an extent, that we wondered whether we belonged here. Our school syllabus taught the Great Trek but only a few of us learnt about the discovery of gold. No textbook ever explained that gold had paid for the rest of South Africa’s infrastructure. Then we had Councillors like Francis Oberholzer who famously said, “Why would any tourist want to visit Johannesburg?” but if you look at the tourist guides from the 1890s to 1928. the Rand was considered the peak of any trip. Every mine was featured in a post card: the cyanide tanks, the dumps, the lakes, the headgear. Later the Council didn’t promote tourism, and the mining community didn’t want conservationists interfering with their property development plans. Big business joined the plot to pretend Johannesburg had no history or heritage worth mentioning. They certainly didn’t want any sentimental controls to prevent them from knocking down and rebuilding the city centre every 16 years.

‘It took the new regime to remind us that Joburg is quite as beautiful as Pretoria, probably has more Jacarandas, and it has a very proud history of opposing apartheid. We’ve acknowledged that Soweto is not a black hole but a fascinating and very proud part of the city, for so long hidden and not even named on maps. Johannesburgers love living here because it offers huge variety, beautiful suburbs and it’s both exciting and a little bit dangerous. White people are still scared of coming back into town but they are improving. Time was when we offered a centre city tour we had to bus people or drive in convoy. Recently, people on one of our tours, drove boldly into Ferreirastown, parked their cars and walked.’

Johannesburg! (The Heritage Portal)

Denis Adams, long time Vice Chairman to Flo Bird on the P&W HT, offers these observations on the woman with whom he has worked for over 20 years. ‘I have never known such energy and enthusiasm to come so consistently from one person. She knows so much about Johannesburg that she’s probably forgotten more than I’ll ever learn. Her ability to see both sides of a question and her passion to do what is right and fair is well and widely known. So too is her ability to express her views in terms both blunt and explicit. She’ll continue to do this, terrier-like, until both sides reach an acceptable solution. She balances the important things in life. Her family time. With Johnny, her spouse of over forty years, her three children and her loved and loving grandchildren, is precious. Nobody can interfere with this! She organizes her time to do less noticeable things, particularly for the underprivileged.’

Main image: Old photo of Flo Bird with Dennis Adams

Note from Kathy Munro, July 2020: The Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust transformed into the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation in 2012 recognising its broader geographical reach. By that date the Johannesburg Historical Foundation had ceased to exist and there was a gap in the field of Johannesburg heritage. Who cared about the Johannesburg landscape and its culture? Flo and her team continued to extend the reach of the old Parktown and Westcliff society to more parts of Johannesburg. Flo served as the Founding Chairperson of the JHF from 2012 to 2015. Wits, her alma mater awarded her a prestigious Gold Medal in 2014. Brett McDougall was the chair from 2015 to 2019 and I took over as Chair in mid 2019. Flo and Brett are now the Vice Chairs. Flo is still an active campaigner and driver of heritage concerns, a doughty fighter for the cause of heritage, ever the optimist even in times of the Covid pandemic. These days Flo leads the team at the JHF Research resource centre and library at the Holy Family College. JHF has a membership of about 300 members including 8 residents associations. Flo Bird is the person who has given Johannesburg an awareness of its134 year history and heritage and its unique Witwatersrand mining and geographical context.

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.